Geographies of Cultural Difference

42

CHAPTER 2

MANY WORLDS

Geographies of Cultural Difference

What can this scene tell us about nature-culture relations in North American popular culture?

Enjoying nature in a national park campground.

(Courtesy of Roderick Neumann.)

Go to “Seeing Geography” to learn more about this image.

43

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

▪2.1

Explain the role of cultural difference in shaping regions.

▪2.2

Describe the ways that mobility interacts with cultural difference.

▪2.3

Analyze the potential for globalizing processes to shape and be altered by cultural difference.

▪2.4

Identify the influence of culture on physical geography and physical geography on culture.

▪2.5

Recognize how landscapes reflect cultural differences.

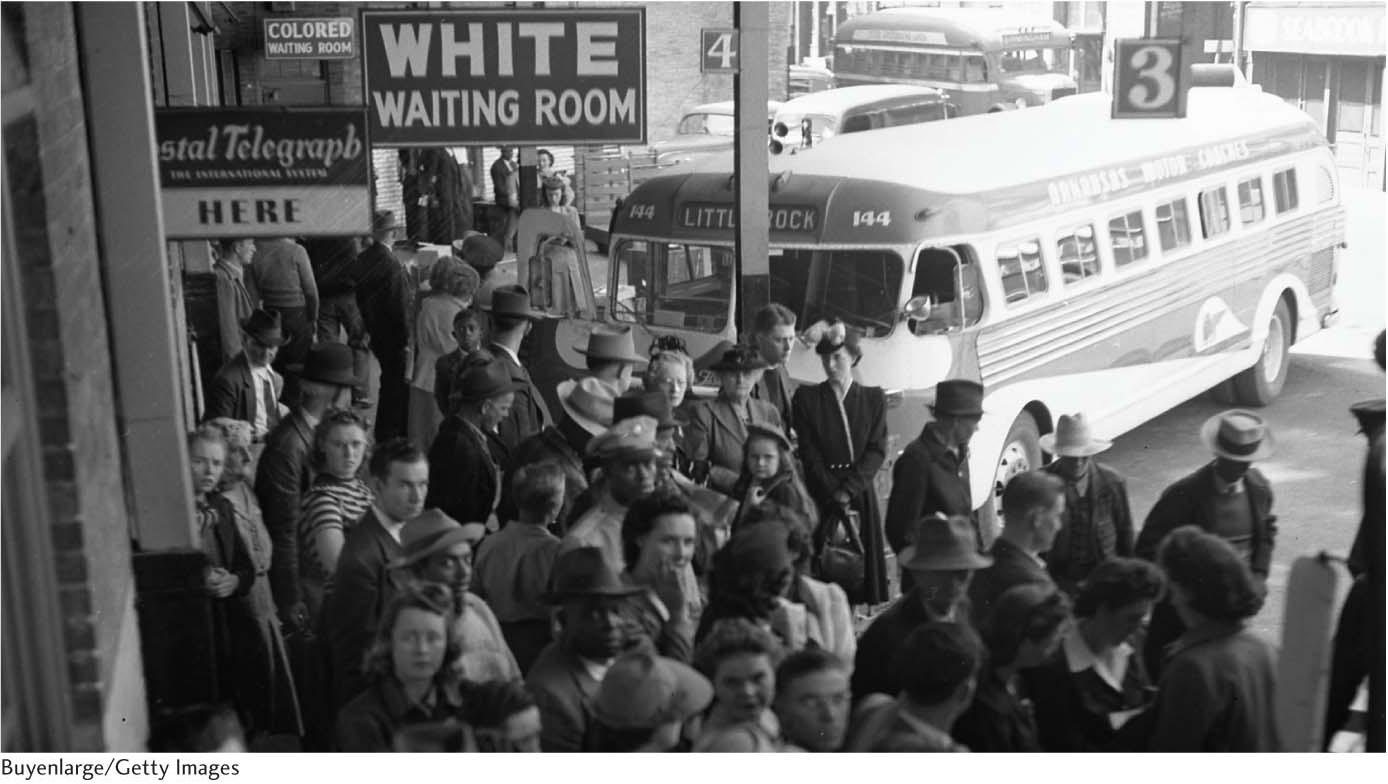

No matter where we live, if you look carefully, you will see how important cultural identity is to our daily lives. Cultural difference is evident everywhere—not only in the geographic distribution of different cultures but also in the way that difference is created or reinforced by geography. For example, in the United States, the historical legacy of segregating “Whites” from “Blacks” has been important in establishing and maintaining cultural differences between these groups (Figure 2.1).

In Chapter 1, we noted that human geographers are interested in studying the geographic differences both among and within cultures. For example, using the concept of formal region (a region inhabited by people who have one or more cultural traits in common), we can identify and map differences among cultures. This sort of analysis is usually done on a very large geographic scale, such as a continent or even the entire world. But, geographers are also interested in analyses at smaller scales. When we look more closely at a formal culture region, we begin to see that differences appear along racial, religious, gender-related, and other lines of distinction. Sometimes groups within a dominant culture become distinctive enough that we label them subcultures. These can be the result of resistance to the dominant culture or of a separate religious, ethnic, or national group forming its own distinct community within a larger culture (Figure 2.2).

subcultures

Groups of people with norms, values, and material practices that differentiate them from the dominant culture to which they belong.

We also noted in Chapter 1 that there are many ways of defining and categorizing cultures. In this chapter, we will begin to explore the vast range of geographies of culture difference. The term difference implies a relationship and a set of criteria for comparison and assessment. That is, cultures are defined as they relate to each other using a predetermined set of characteristics. But, what does it mean to speak of geographies in the plural? Isn’t there only one geography? The plural form emphasizes that there is no single way of seeing and experiencing place and landscape. Recall from Chapter 1 our discussion on the concept of personal experience in the sense of place, which emphasizes the multiplicity of meanings versus a single, universally shared meaning. Cultural geography studies have shown, for example, that women and men often experience the same places in different ways. A certain street corner or tavern might be a comfortable and familiar hangout for men but a threatening or uncomfortable zone that women avoid (see Seeing Geography, Chapter 3). To speak of geographies, then, is to go beyond the idea of a single way of looking at the world and raise new questions about the different meanings that people give to places and landscapes: how these relate to their sense of self and belonging; and how, in multicultural societies, we deal with these different meanings politically and socially.

44

MANY CULTURES

We classify cultures using many different criteria, both material and nonmaterial. Material culture includes the physical objects made and/or used by members of a cultural group: buildings, furniture, clothing, artwork, musical instruments, and so forth. The elements of material culture are visible. Nonmaterial culture includes the wide range of beliefs, values, myths, and symbolic meanings passed from generation to generation of a given society. Often it is difficult to draw clear lines between material and nonmaterial features of culture. Food, for example, is material, but it is also charged with symbolic meaning and valued differently in different cultures (Figure 2.3). Many Westerners would gag at the mere thought of eating the worms and insects that are the daily food staples and even much valued delicacies in non-Western, rural cultures around the world. Therefore, cultures can be thought of in terms of both material and nonmaterial characteristics.

material culture

All physical, tangible objects made and used by members of a cultural group, such as clothing, buildings, tools and utensils, instruments, furniture, and artwork; the visible aspect of culture.

nonmaterial culture

The wide range of tales, songs, lore, beliefs, values, and customs that pass from generation to generation as part of an oral or written tradition.

45

Let’s look briefly at how these material and nonmaterial characteristics were first used to identify, categorize, and map cultures. In eighteenth-century Europe and North America, people first began to speak of “cultures” in the plural form. Specifically, following Europe’s Age of Exploration and Discovery (when Europeans began to explore the world by sea), they started thinking about “European culture” in relation to other cultures they encountered around the world. Although now discredited as ethnocentric and racist, hierarchical models—in which European culture was ranked above other cultures—were invented to categorize and rank cultures. Religion and technology were key criteria in constructing these hierarchies, with Christian and technologically developed cultures ranked at the top and non-Christian, nonindustrial cultures ranked at the bottom.

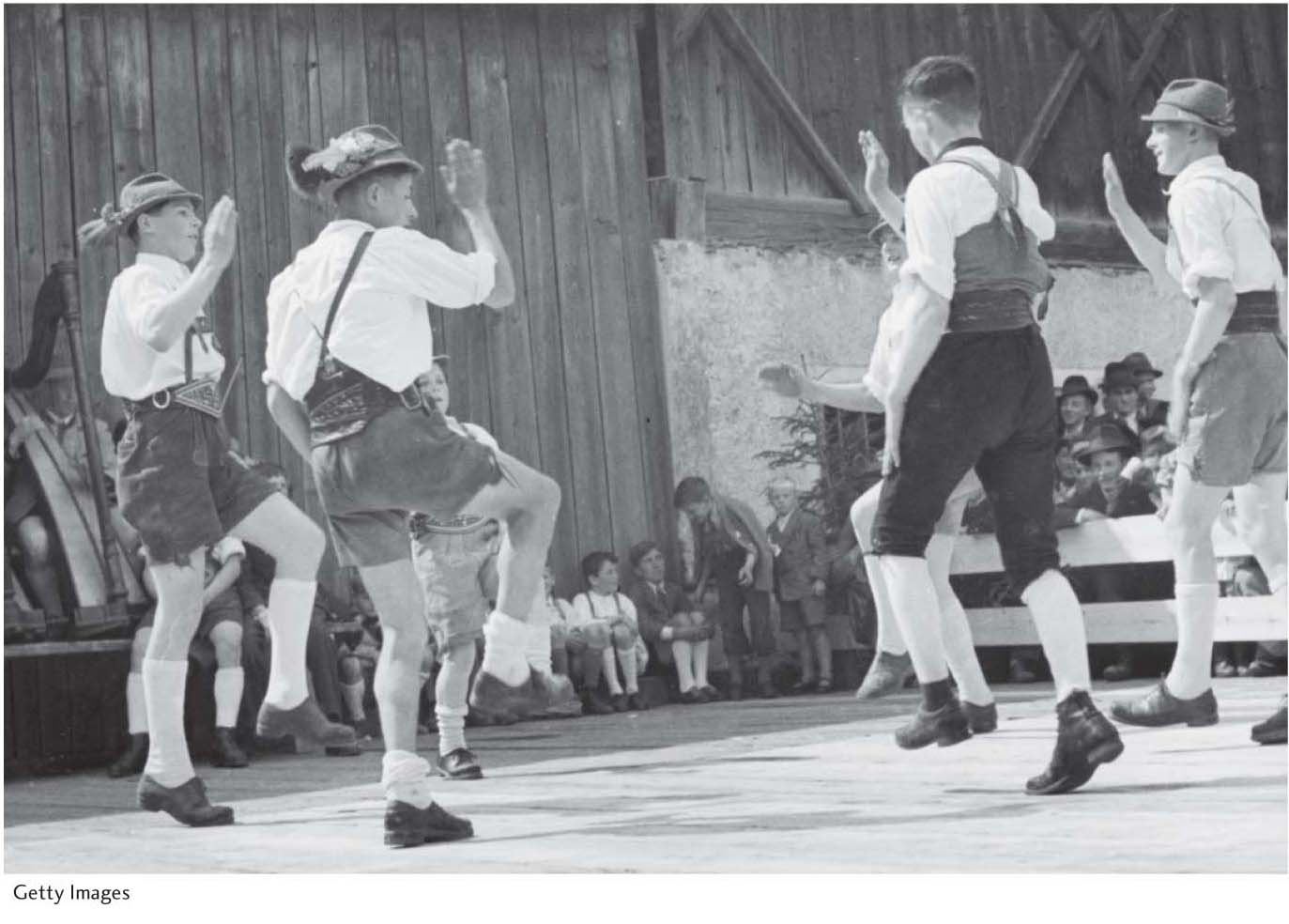

Folk Culture As Europe and North America industrialized and urbanized in the nineteenth century, people began thinking in terms of internal cultural differences between groups. Urban city dwellers started to view rural country spaces as inhabited by distinct cultures. Thus, a new term, folk culture, was invented to distinguish traditional ways of life in rural and agricultural spaces from ways of life in the new urban and industrial spaces. When Europe’s kingdoms and empires fragmented into new countries throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, the urbanized, cosmopolitan elites looked to the rural folk as the source of distinctive national identities (Figure 2.4). Similarly, as the United States urbanized and expanded westward, rural folk were seen as the source of an American national character defined by self-reliance, perseverance, and a pioneering spirit. Hence, the cowboy—an economically minor and short-lived rural occupation in the nineteenth-century western United States—came to symbolically embody the imagined American national character. Folk culture and national culture thus have been closely associated. The term national culture, sometimes regarded as a controversial idea, suggests that a country’s population possesses a set of recognizable characteristics or traits—often including the same ethnic and linguistic traits—that express the core culture of each modern nation. Hence, many countries have museums and institutes dedicated to the celebration of folk culture and its relevance to contemporary national identity (Figure 2.5).

folk culture

Rural, unified, largely self-sufficient groups that share similar customs and ethnicity. In terms of material culture, many items of daily use such as clothing, furniture, and housing are handmade, often from raw materials found locally. Most food is grown and consumed locally.

national culture

The controversial idea that citizens possess a set of recognizable values, behaviors, and beliefs—often including the same ethnic and linguistic traits—that express the core culture of each modern nation.

46

Folk culture is defined as rural, unified, largely self-sufficient groups that share similar customs and ethnicity. In terms of material culture, many items of daily use such as clothing, furniture, and housing are handmade, often from raw materials found locally. Most food is grown and consumed locally, which often has resulted in the formation of distinctive regional cuisines, such as the Japanese diet of rice and raw fish or the Mesoamerican diet of maize, beans, and spicy peppers. In terms of nonmaterial culture, folk cultures typically have strong family or clan structures and highly localized rituals, such as an annual blessing of water wells and springs or harvest dances. Generations of gifted individuals within folk communities create songs, musical styles, and storytelling that are unique to their region. As with food, folk cultures often produce distinctive, highly regionalized musical genres, Appalachian bluegrass music being one well-known example. In Europe and North America, folk cultures, strictly defined, no longer exist, though many material and nonmaterial traces can be found in the landscape. Moreover, the reasons for the creation of folk cultures —human inventiveness, curiosity, and need, uniquely expressed in specific places—endure, as we will illustrate throughout this textbook.

Indigenous Culture Today, geographers frequently use terms such as local, place-based, or indigenous when referring to some of the distinctive cultural traits typically associated with folk culture. Indeed, the concept of indigenous culture has emerged as a focus of study in cultural geography. A simple definition of indigenous is “native” or “of native origin.” In the modern world of independent countries, the word has acquired much greater cultural and political meanings. The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention 169 (Article 1.1) presents a legal definition that recognizes indigenous peoples as comprising a distinct culture. According to the ILO, indigenous peoples are self-identified tribal peoples whose social, cultural, and economic conditions distinguish them from the national society of the country in which they live (Figure 2.6). As with folk cultures, indigenous cultures are generally associated with nonurban, rural spaces, particularly the isolated forests and mountain ranges of the world.

indigenous culture

A culture group that constitutes the original inhabitants of a territory, distinct from the dominant national culture, which is often derived from colonial occupation.

Indigenous peoples are regarded as descending from peoples present in a territory at the time of conquest or colonization by an external empire or civilization. Although indigenous peoples may share some of the material and nonmaterial characteristics that define folk cultures, their histories (and geographies) are quite different. Indigenous cultures are, in effect, those peoples who were colonized—mostly, but not exclusively—by European cultures and are now minorities in their homelands. Whereas folk culture was seen as providing the foundation for a national culture, indigenous culture is usually positioned in opposition to national culture.

47

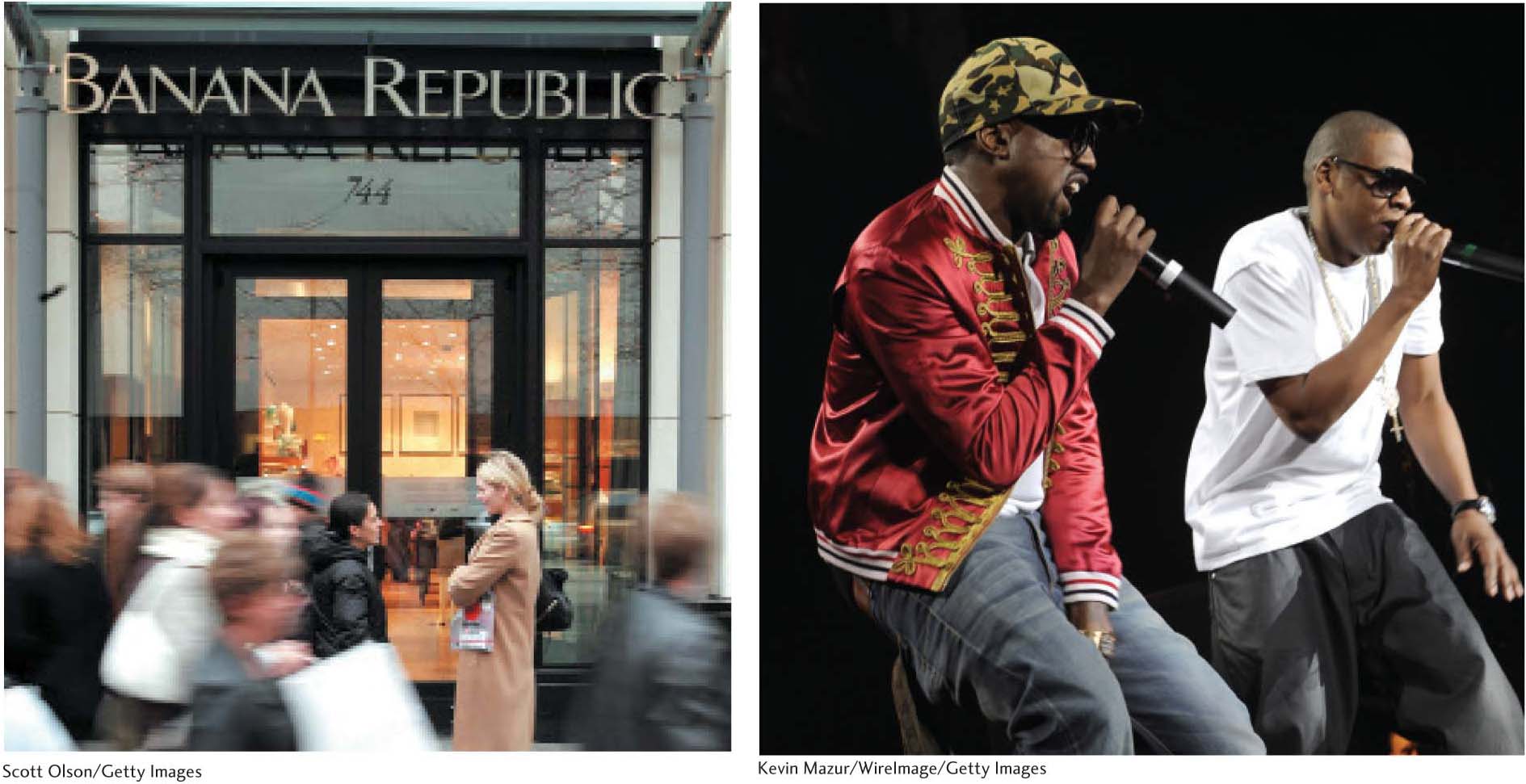

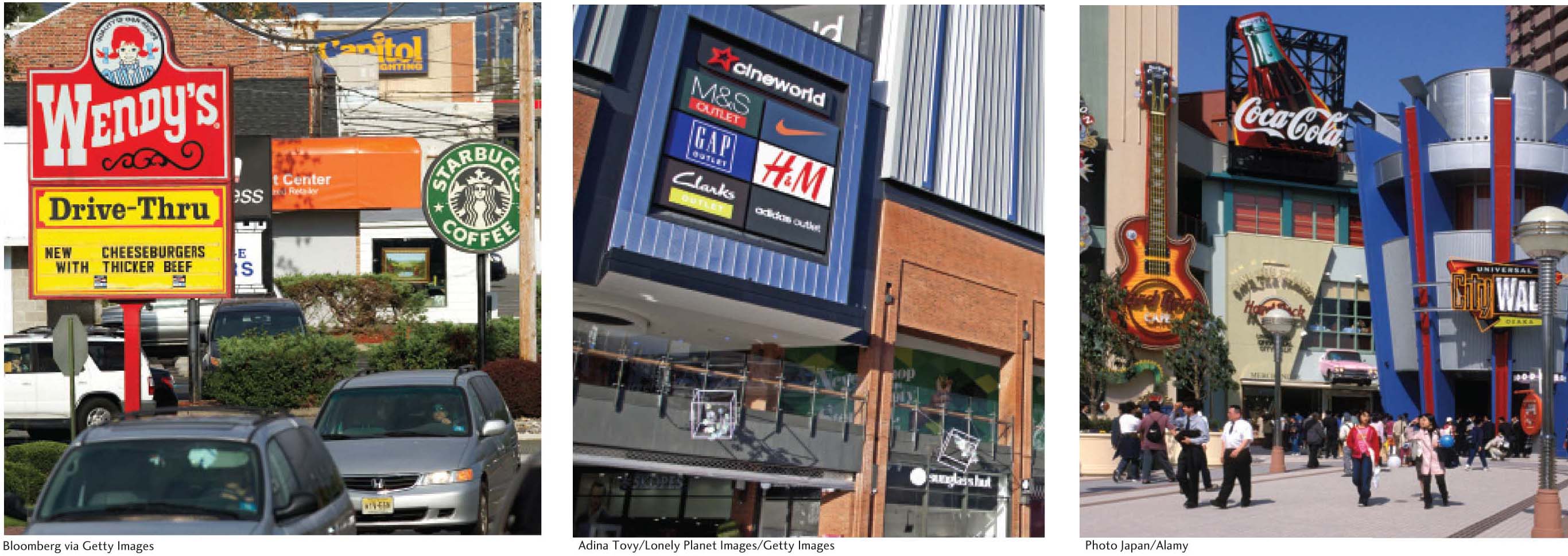

FROM FOLK CULTURE TO POPULAR CULTURE

The notion of folk cultures emerged historically when urban elites began to fear that the ways of traditional, rural life were being erased and replaced by the rapid spread of popular culture. Popular culture refers to modern ways of life associated with the rise of mass-produced, machine-made goods and the invention of long-distance communication technologies (Figure 2.7). People sometimes use the terms mass culture and consumer culture to mean the same thing as popular culture. “Mass” emphasizes that popular culture is widespread, undifferentiated, and placeless. Mass media such as the Internet, film, print, television, and radio, and are influential in shaping popular culture. “Consumer” emphasizes that popular cultural identity is shaped through the purchase and consumption of mass-produced commodities. Finally, geographer Edward Relph suggests that popular culture is characterized by a profound placelessness, a feeling resulting from the standardization of the built environment that diminishes regional variation and eliminates the unique meanings associated with specific locations (Figure 2.8). Shopping malls, airports, and global hotel and fast-food chains are examples of placeless locations that could be anywhere. One could travel, for instance, to Beijing, China, stay overnight at the airport Hilton much like any other Hilton across the world, eat steak and mashed potatoes for dinner much like one would order in any major city, shop for shoes at the global chain stores in the airport mall while waiting for one’s flight, and never experience anything Chinese or unique to Beijing.

popular culture

Broadly defined, the modern ways of life associated with the rise of mass-produced, machine-made goods and the invention of long-distance communication technologies that collectively shape cultural preferences and define cultural identity.

placelessness

A spatial standardization that diminishes regional variety; may result from the spread of popular culture, which can diminish or destroy the uniqueness of place through cultural standardization on a national or even worldwide scale.

48

In popular culture, people are more mobile and less likely to live their lives in a single place. Secular institutions of authority—such as schools and courts—become increasingly important for maintaining social order. Individual choice is highly valued. Social relationships multiply, but fewer of them are conducted face to face. Rather, relationships become “stretched” across time and space. Think of online credit card purchases in contrast to the bartering that took place in the local village markets of historic folk cultures. Whereas the latter exchange was conducted in person between two people, think of how many individuals and corporations are involved in an online credit card purchase and home delivery of a simple pair of shoes, and how geographically distant from one another they are.

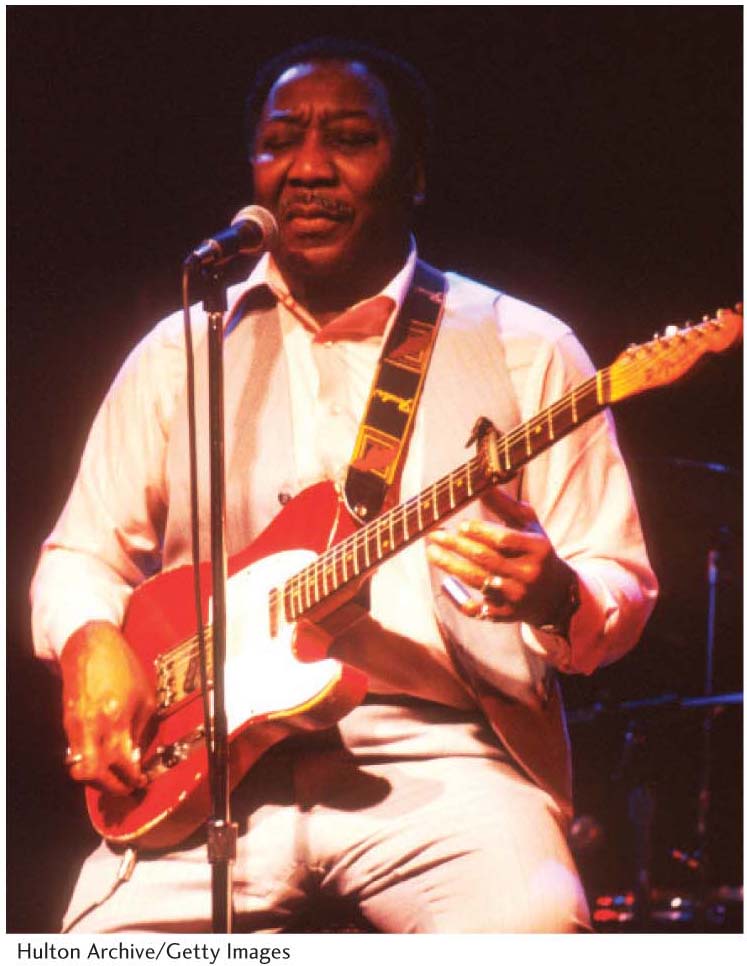

Just as the line between the material and the nonmaterial elements of culture is blurry, so too is the line between elements of folk and popular culture. For example, blues music had its origins among African American folk culture in the U.S. South, particularly the Mississippi Delta region (Figure 2.9). Later, in the 1950s, blues evolved into rock and roll, a musical genre that has come to epitomize global popular culture. There are many more examples of folk or indigenous cultural characteristics that have been incorporated into popular culture, including foods, textiles, and architecture. Conversely, items of popular culture have been incorporated into rural, folk-oriented cultures in surprising new ways. For example, the introduction of cheap, mass-produced glass beads from Europe provided the basis for vibrant new art forms in many Native American cultures (Figure 2.10). Thus, our interest in Contemporary Human Geography is not to draw distinct boundaries between different cultural types, but rather to explore how the materials, ideas, and symbols of one type of culture are adopted and reinterpreted by other cultures.

49

Mobility and Diversity To say that the elements of popular culture are defined by the rise of mass production, consumption, transportation, and communication is not to say that the growth of popular culture has followed a single, set pattern. Far from it. For example, greater mobility means that local, ethnically distinct cultures are frequently transplanted to faraway regions and cities where they form recognizable enclaves and contribute greatly to cultural diversity. Cities around the world are dotted with neighborhoods called “Little Italy,” “Chinatown,” “Little Haiti,” “Germantown,” and so on (Figure 2.11). Geographers increasingly refer to such transplanted ethnic, racial, and national population concentrations as diaspora cultures. Historically, diaspora referred to a people (especially ancient Jewish culture) that had been displaced and geographically scattered. With the rise of globalization, however, international mobility has increased the size and number of diaspora cultures around the globe. Often diaspora cultures maintain strong social and economic ties to their homelands and therefore display hybrid or multiple cultural identities.

diaspora culture

Ethnic, racial, and national population concentrations of people displaced and geographically scattered from their homelands. Such displaced groups often maintain strong social and economic ties to their homelands.

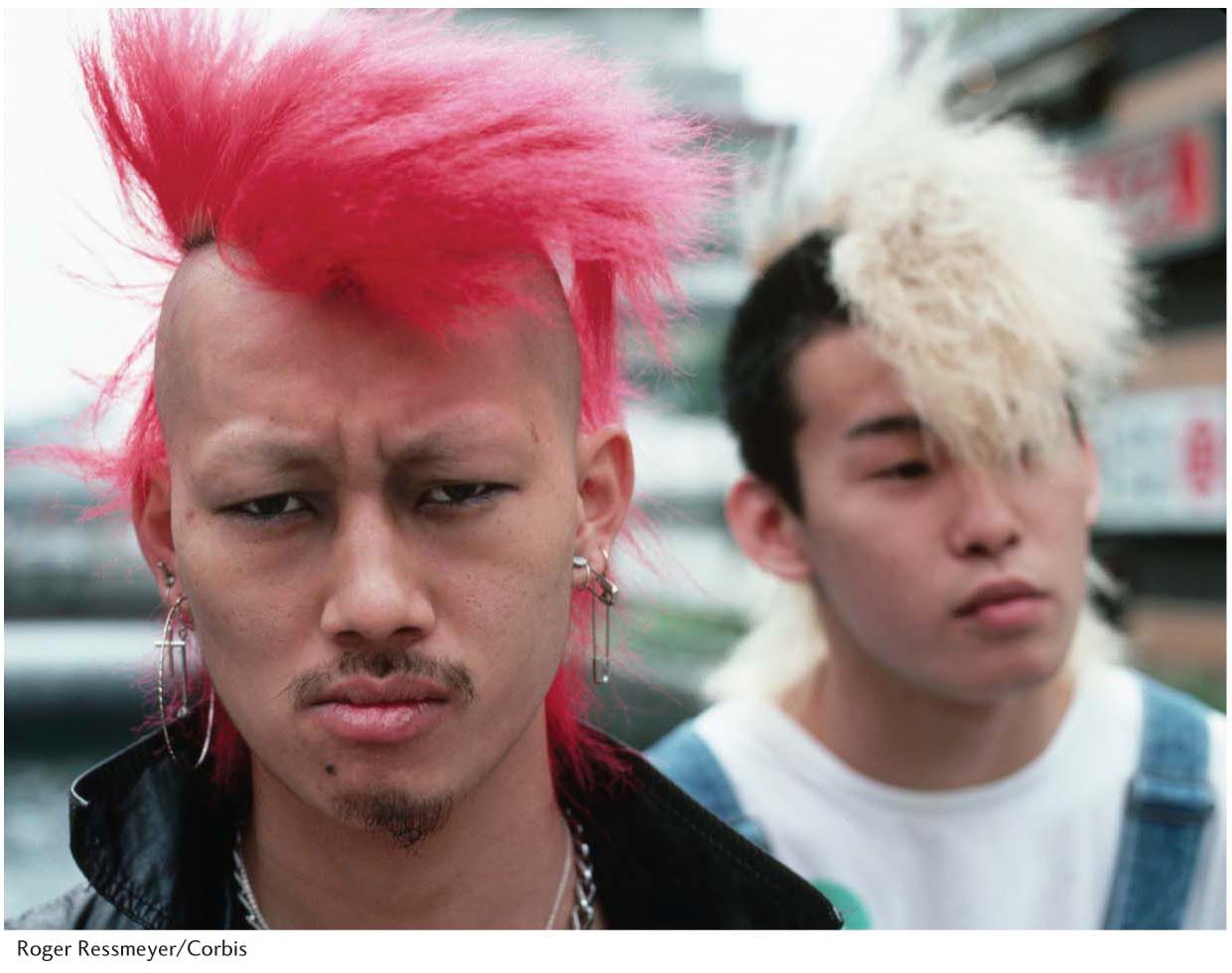

In addition to the diversity produced through increased global mobility, popular culture is subject to endless diversification into subcultures through the reuse and reinterpretation of mass-produced goods. Think of the importance of safety pins—a common household item originally associated with motherhood and diapers—to the material expression of punk culture (Figure 2.12). The list of such subcultures emerging under globalization is nearly infinite. Gay, hip-hop, NASCAR, and grunge are just a few of the adjectives that we place before “culture” to talk about popular cultural identities, each with its particular geographic expression. Culture is as dynamic and limitless as the human imagination. We can use our five themes—region, mobility, globalization, nature-culture, and cultural landscape—to study the ongoing generation of geographies of cultural difference.

50