GLOBALIZATION

2.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze the potential for globalizing processes to shape and be altered by cultural difference.

The effects of globalization on cultural difference and vice versa are a much discussed and debated issue for geographers and other social scientists. As we look for evidence in real-world examples, we find that the answer is less than straightforward.

FROM DIFFERENCE TO CONVERGENCE

Globalization is most directly and visibly at work in popular culture. Increased leisure time, instant communications, greater affluence for many people, heightened mobility, and weakened attachment to family and place—all features of popular culture—have the potential, through interaction, to cause massive spatial restructuring. Most social scientists long assumed that the result of such globalizing forces and trends, especially mobility and the electronic media, would be the homogenization of culture, wherein the differences among places are reduced or eliminated. This assumption is called the convergence hypothesis; that is, cultures are converging, or becoming more alike. In the geographical sense, this would yield placelessness, a concept discussed earlier in the chapter.

convergence hypothesis

A hypothesis holding that cultural differences among places are being reduced by improved transportation and communications systems, leading to a homogenization of popular culture.

DIFFERENCE REVITALIZED

Globalization, we should remember, is an ongoing process or, more accurately, set of processes. It is incomplete and its outcome far from predetermined. Geographer Peter Jackson is a strong proponent of the position that cultural differences are not simply obliterated under the wave of globalization. For Jackson, globalization is best understood as a “site of struggle.” He means that cultural practices rooted in place shape the effects of globalization through resistance, transformation, and hybridization. In other words, globalization is not an all-powerful force. People in different places respond in different ways, rejecting outright some of what globalization brings while transforming and absorbing other aspects into local culture. Rather than one homogeneous globalized culture, Jackson sees multiple local consumption cultures.

local consumption cultures

Distinct consumption practices and preferences in food, clothing, music, and so forth formed in specific places and historical moments.

Local consumption culture refers to the consumption practices and preferences—in food, clothing, music, and so on—formed in specific places and historical moments. These local consumption cultures often shape globalization and its effects. In some ways, globalization revitalizes local difference. That is, people reject or incorporate into their cultural practices the ideas and artifacts of globalization and in the process reassert place-based identities.

68

For example, when England-based Cadbury decided to market its line of chocolates and confections in China, the company was forced to conform to local practices. Unlike much of Europe and North America, China had no culture of impulse buying and no tradition of self-service. Cadbury had to change the names of its products, eschew mass marketing, focus on a small group of high-end consumers, and even change product content. Jackson suggests that the introduction of Cadbury’s chocolate to China is more than simply another sign of globalization. He argues that the case “demonstrates the resilience of local consumption cultures to which transnational corporations must adapt.”

In cases where companies’ products are negatively associated with their place of origin, such as exports from apartheid South Africa, the global ambitions of multinational companies can be thwarted. In such cases, labeling and advertising must mask the geographic origin of products lest global markets reject them. “Local” circumstances thus can make a difference to the outcomes of globalization.

Local resistance to globalization often takes the form of consumer nationalism. This occurs when local consumers avoid foreign companies or imported products and favor domestic businesses and products (Figure 2.40). India and China, in particular, have a long history of resisting outside domination through boycotts of imported goods. Jackson discusses a recent case in China in which Chinese entrepreneurs invented a local alternative to Kentucky Fried Chicken called Ronghua Fried Chicken Company. The company uses what it claims are traditional Chinese herbs in its recipe, delivering a product more suitable to Chinese cultural tastes.

consumer nationalism

A situation in which local consumers favor nationally produced goods over imported goods as part of a nationalist political agenda.

PLACE IMAGES

The same media that serve and reflect the rise of personal preference—movies, television, photography, music, advertising, art, and others—often produce place images, a subject studied by geographers Brian Godfrey and Leo Zonn, among others. Place, portrayer, and medium interact to produce the image, which, in turn, colors our perception of and beliefs about places and regions we have never visited. The focus on place images highlights the role of the collective imagination in the formation and dissolution of culture regions. It also explores the degree to which the image of a region fits the reality on the ground. That is, in imagining a region or place, often certain regional characteristics are stressed, whereas others are ignored (see Subject to Debate).

The images may be inaccurate or misleading, but they nevertheless create a world in our minds that has an array of unique places and place meanings. Our decisions about tourism and migration can be influenced by these images. For example, through the media, Hawaii has become in the American mind a sort of earthly paradise peopled by scantily clad, eternally happy, invariably good-looking natives who live in a setting of unparalleled natural beauty and idyllic climate. People have always formed images of faraway places. Through the interworkings of popular culture, these images proliferate and become more vivid, if not more accurate.

69

Subject To Debate: Mobile Identities: Questions of Culture and Citizenship

Subject To Debate

MOBILE IDENTITIES: Questions of Culture and Citizenship

One of the most dynamic features of cultural difference in the world today is mobility. Diaspora communities have sprung up around the globe. Some of these communities have arisen quite recently and are historically unprecedented, such as the movement of Southeast Asians into U.S. cities in the late twentieth century. Some are artifacts of European colonialism, such as the large populations of South Asians in England or West and North Africans in France. Others are deeply historical and express a centuries-old interregional linkage, such as the contemporary movement of North Africans into southern Spain.

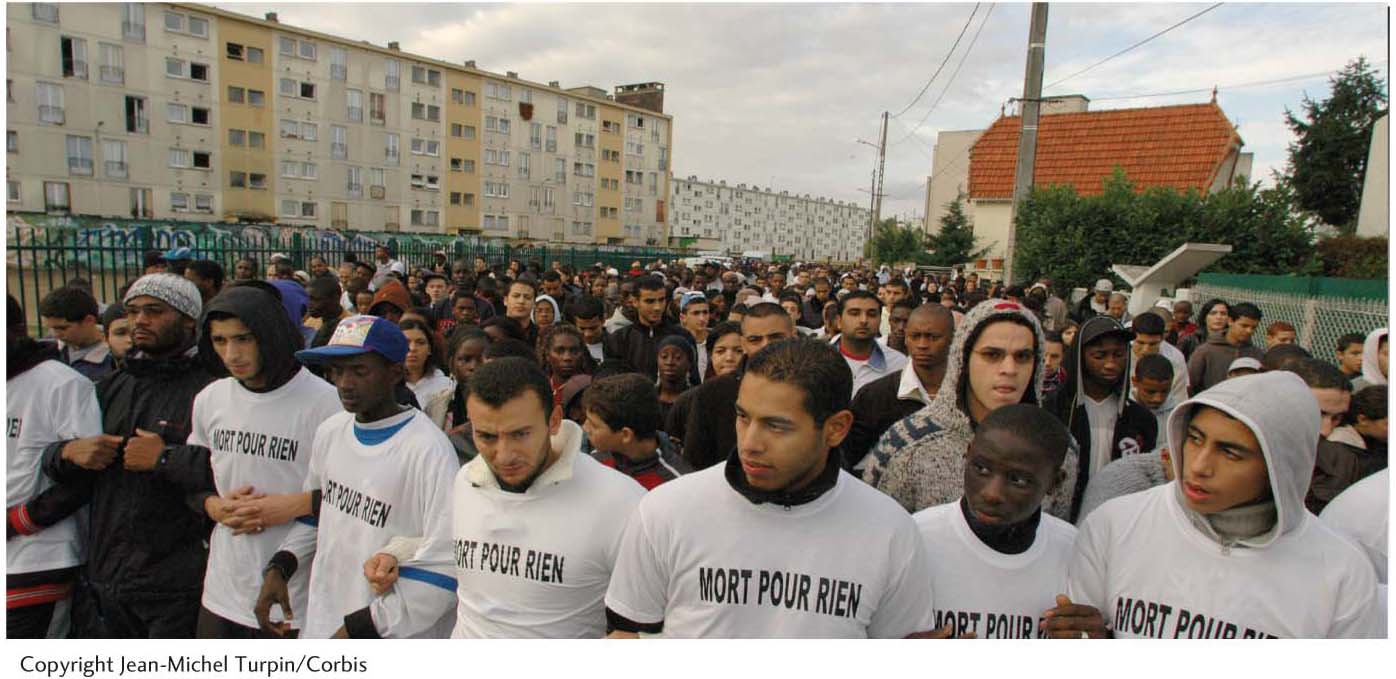

The movement and settlement of large populations of migrants have raised questions of belonging and exclusion. How do transplanted populations become English, French, or Spanish, not only in terms of citizenship but also in terms of belonging to that culture? Some observers have argued that diaspora populations find ways to blend symbols from their cultures of origin with those of their host cultures. Thus, people develop a sense of belonging through a process of cultural hybridization. Other observers point to long-standing situations of cultural exclusion. In 2005 in France, for example, riots broke out in more than a dozen cities in suburban enclaves of West African and North African populations. The reasons for the riots are complex. However, many observers pointed out that underprivileged youth of African descent feel excluded from mainstream French culture, even though many are second- and third-generation French citizens.

The debate over how to address questions of citizenship and cultural belonging is played out in many venues. In terms of policy, the French, for example, emphasize cultural integration; for example, the French government approved a law in 2010 banning full-face veils (burqas ) in public, whereas Britain and the United States promote multiculturalism. But many questions remain about the effectiveness of state policies toward diaspora cultures.

Continuing the Debate

Based on the discussion presented above, consider these questions:

•Do the geographic enclaves of Asian and African diaspora populations in the former colonial capitals of Europe reflect an effort by migrants to retain a distinct cultural identity? Or do they reflect persisting racial and ethnic prejudices and efforts to segregate “foreigners”? Or is it a combination of factors?

•How long does it take an Asian immigrant community to become “English” or a West African immigrant community to become “French”? One generation? Two? Never?

•Does the presence of Asians and Africans make the landscape of England and France appear less “English” or less “French”? Why or why not?

70

LOCAL INDIGENOUS CULTURES GO GLOBAL

The world’s indigenous peoples often interact with globalization in interesting ways. On the one hand, new global communications systems, institutions of global governance, and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are providing indigenous peoples with extraordinary networking possibilities. Local indigenous peoples around the world are now linked in global networks that allow them to share strategies, rally international support for local causes, and create a united front to defend cultural survival. On the other hand, globalization brings the world to formerly isolated cultures. Global mass communications introduce new values, and multinational corporations’ search for new markets and new sources of gas, oil, genetic, forest, and other resources can threaten local economies and environments.

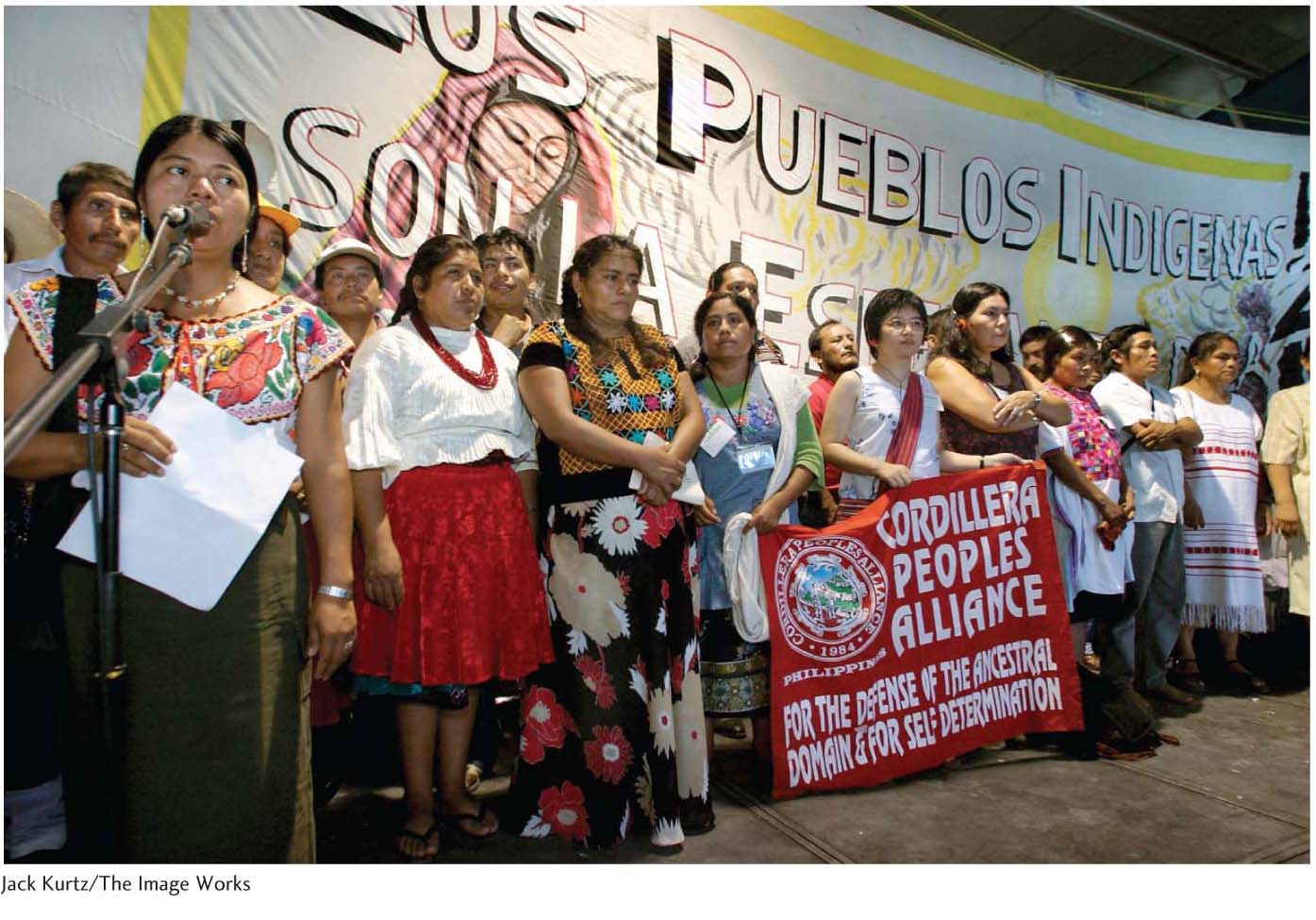

Both aspects of indigenous peoples’ interactions with globalization were evident at the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Ministerial Conference in Cancún, Mexico, in 2003. Indigenous peoples’ organizations from around the world gathered for the conference, hosted by the Mayan community in nearby Quintana Roo. Though not officially part of the conference, they came together there to strategize ways to forward their collective cause of cultural survival and self-determination, gain worldwide publicity, and protest the WTO’s vision of globalization (Figure 2.41). One outcome of this meeting was the International Cancún Declaration of Indigenous Peoples (ICDIP), a document highly critical of current trends in globalization.

According to the ICDIP, the situation of indigenous peoples globally “has turned from bad to worse” since the establishment of the WTO. Indigenous rights organizations claim that “our territories and resources, our indigenous knowledge, cultures and identities are grossly violated” by international trade and investment rules. The document urges governments worldwide to make no further agreements under the WTO and to reconsider previous agreements. The control of plant genetic resources is a particularly important concern. Many indigenous peoples argue that generations of their labor and cumulative knowledge have gone into producing the genetic resources that transnational corporations are trying to privatize for their own profit. The ICDIP asks that future international agreements ensure “that we, Indigenous Peoples, retain our rights to have control over our seeds, medicinal plants and indigenous knowledge.”

Globalization is clearly a critical issue for indigenous cultures. Some argue that globalization, because it facilitates the creation of global networks that provide strength in numbers, may ultimately improve indigenous peoples’ efforts to control their own destinies. The future of indigenous cultural survival ultimately will depend on how globalization is structured and for whose benefit.

71