GLOBALIZATION

4.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe the relationship between technology and language.

More often than not, the diffusion of some languages has come at the expense of many others. Ten thousand years ago, the human race consisted of only 1 million people, speaking an estimated 15,000 languages. Today, a population 7000 times larger speaks only 47 percent as many tongues. Only 1 percent of all languages have as many as 500,000 speakers. It has been estimated that the world loses a language on average every two weeks. Some experts believe that all but 300 languages will be extinct or dying by the year 2100. Clearly, globalization has worked to favor some languages and eliminate others. According to linguist Suzanne Romaine, there are no children today who are learning any of California’s nearly 100 native languages. Languages die out when their speakers do; often the entire cultural world associated with a language vanishes as well. Thus, globalization both presents the opportunity for more people to communicate directly with one another and, at the same time, threatens to extinguish the cultural diversity that goes hand-in-hand with linguistic diversity.

TECHNOLOGY, LANGUAGE, AND EMPIRE

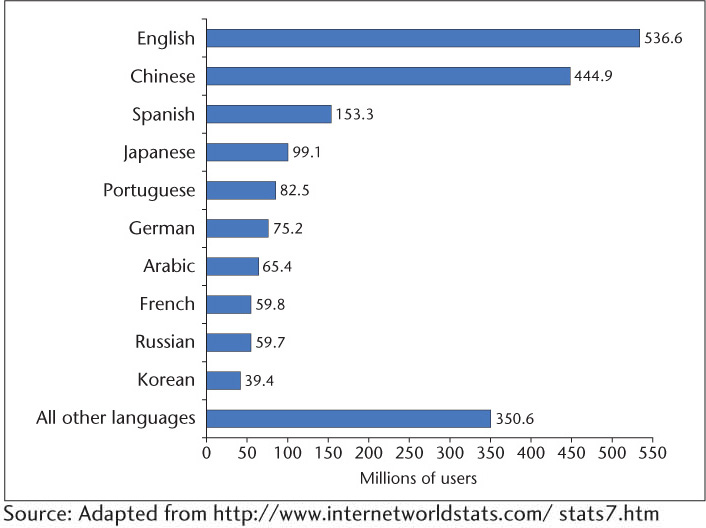

Technological innovations affecting language range from the basic practice of writing down spoken languages to the sophisticated information superhighway provided by the Internet. Technological innovations have in the past facilitated the spread and proliferation of multiple languages, but more recently they have encouraged the tendency of only a few languages—especially English, but also Chinese and Spanish—to dominate all others (Figure 4.9). Particular language groups achieve cultural dominance over neighboring groups in a variety of ways, often with profound results for the linguistic map of the world. Technological superiority is usually involved. Earlier, we saw how plant and animal domestication—the technology of the “agricultural revolution”—aided the early diffusion of the Indo-European language family.

151

153

An even more basic technology was the invention of writing, which appears to have developed as early as 5300 years ago in several hearth areas, including in Egypt, among the Sumerians in what is today Iraq, and in China. Writing helped civilizations develop and spread, giving written languages a major advantage over those that remained spoken only. Written languages can be published and distributed widely, and they carry with them the status of standard, official, and legal communication.

Written language facilitates record keeping, allowing governments and bureaucracies to develop. Thus, the languages of conquerors tend to spread with imperial expansion. The imperial expansion of Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, Spain, and the United States across the globe altered the linguistic practices of millions of people. This empire building superimposed Indo-European tongues on the map of the tropics and subtropics. The areas most affected were Asia, Africa, and the Austronesian island world. A parallel case from the ancient world is China, also a formidable imperial power that spread its language to those it conquered. During the Tang dynasty (618-907 C.E.), Chinese control extended to Tibet, Mongolia, Manchuria (in contemporary northeastern China), and Korea. The 4000-year-old written Chinese language proved essential for the cohesion and maintenance of its far-flung empire. Although people throughout the empire spoke different dialects or even different languages, a common writing system lent a measure of mutual intelligibility at the level of the written word. Today, however, the Chinese are concerned about the “Romanization” of their language, as Chinese schools prioritize learning English and youth are not familiar with as many Chinese characters as their parents or grandparents.

154

Even though imperial nations have, for the most part, given up their colonial empires, the languages they transplanted overseas survive. As a result, English still has a foothold in much of Africa, South Asia, the Philippines, and the Pacific islands. French persists in former French and Belgian colonies, especially in northern, western, and central Africa; Madagascar; and Polynesia (Figure 4.10). In most of these areas, English and French function as the languages of the educated elite, often holding official legal status. They are also used as a lingua franca of government, commerce, and higher education, helping hold together states with multiple native languages.

Transportation technology also profoundly affects the geography of languages. Ships, railroads, and highways all serve to spread the languages of the culture groups that build them, sometimes spelling doom for the speech of less technologically advanced peoples whose lands are suddenly opened to outside contacts. The Trans-Siberian Railroad, built about a century ago, spread the Russian language eastward to the Pacific Ocean. The Alaska Highway, which runs through Canada, carried English into Native American refuges. The construction of highways in Brazil’s remote Amazonian interior threatens the native languages of that region.

Another example is the predominance of English on the Internet, which can be understood as a contemporary information highway (Figure 4.11). What will happen when other languages begin to challenge the dominance of English on the Internet? This will inevitably happen sooner or later, although exactly when English will be surpassed by another language is anyone’s guess. For example, from 2000 to 2010 there was a truly impressive 1277 percent growth in the number of Chinese speakers on the Internet. If this trend continues, and when—not if—the 71 percent of Chinese speakers who do not now use the Internet begin to log on, we can expect Chinese to surpass English as the most popular language on the Internet. Speakers of other languages grew even more impressively over this time period. For instance, Arabic-speaking Internet users grew 2501 percent from 2000 to 2010, while speakers of Russian grew 1826 percent over the same period.

Yet, technology can also be employed to preserve and revive endangered languages. Native American groups, for instance, are working with software developers to create language apps for the iPhone and iPad. They are also working to produce toys that speak in Native languages and video games. All of these are intended to preserve and teach Native languages, especially to younger people. Most speakers of Native American languages—around 90 percent—are middle-aged and older, so capturing the interest of younger speakers is vitally important to the survival of these languages. The U.S. government provides federal funds in the form of competitive grants to support language preservation efforts, while some tribes can utilize casino earnings for this purpose. Regardless of the funding source, most Native American groups are engaged in language preservation and instruction. Besides the apps and video games, language immersion schools have been established (Figure 4.12), with mentor relationships forming between elders and youth, YouTube videos of Native speakers are also available, and Google Hangout video chats facilitate live conversations among remotely located individuals.

155

Patricia’s Notebook: Miami State of Mind

Patricia’s Notebook

Miami State of Mind

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

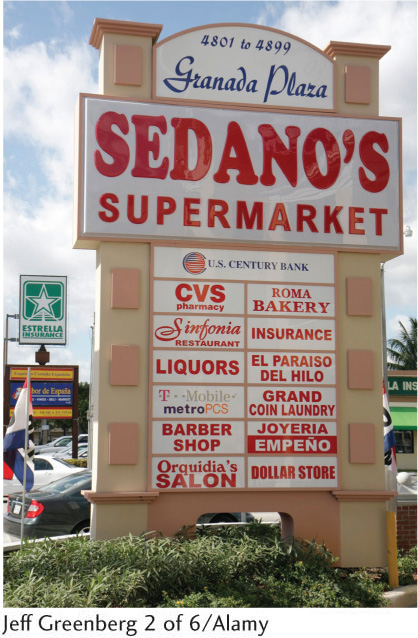

Geographically speaking, Miami—located in the state of Florida—is undoubtedly a part of the United States of America. However, many aspects of life here make visitors and residents alike feel more like they are somewhere else. As novelist Joan Didion wrote, Miami is “a settlement of considerable interest, not exactly an American city as American cities have until recently been understood but a tropical capital: long on rumor, short on memory . . . referring not to New York or Boston or Los Angeles or Atlanta but to Caracas and Mexico, to Havana and to Bogotá and to Paris and Madrid.” The climate is subtropical, with the only real seasonal variation being between the rainy (summer) and dry (winter) months. Even after 19 years, I still miss autumn! Demographically, about 65 percent of residents are Latino, while the rest are roughly evenly split between African- and Anglo-Americans. And the United Nations has ranked Miami number one in the world in terms of the proportion of foreign-born residents (just over 50 percent).

Perhaps the biggest transition for a new arrival to Miami from another U.S. city, however, involves language. Spanish is the lingua franca of Miami. You can get by here just fine without speaking a word of English, though the reverse is not true: monolingual English speakers will struggle to understand and be understood in many areas of their daily lives. In other words, not speaking Spanish is an impediment here, whether in one’s personal transactions or even in the ability to get a job, since many require applicants to understand and speak some Spanish.

I wonder whether Miami will remain this way or whether—as with other so-called immigrant gateways such as New York, San Francisco, and Chicago—immigrants will eventually acculturate, and the lingua franca of this town will transition yet again to English. I can already see this happening with my students, most of whose parents or grandparents are immigrants. Already their Spanish (or Portuguese, or Haitian Kreyol) is limited to what I call “kitchen” status. In other words, their vocabularies are limited, and they speak Spanish or other languages mostly with non-English-speaking relatives. Their children might not fully learn any language beyond English.

152

Subject To Debate: Imposing English

Subject To Debate

Imposing English

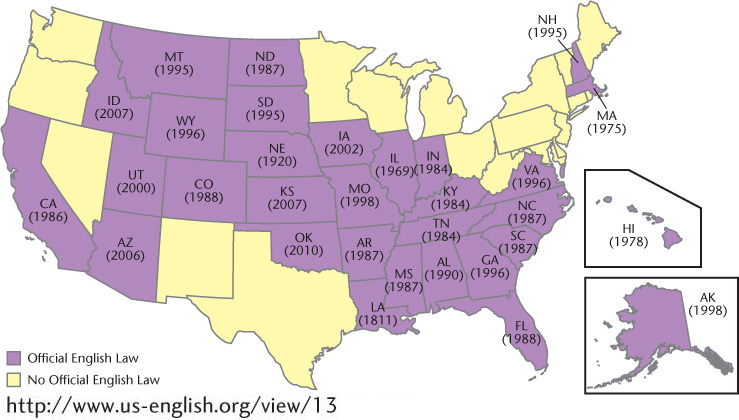

English-only laws are nothing new in the United States. Its history as a nation of immigrants has led to a population that, at any one point in time, has spoken a variety of languages besides English. In its early days as a colony, one could hear German, Dutch, French, and a multitude of Native American languages spoken alongside English. This prompted both Benjamin Franklin and John Adams to propose enforcing English as the sole acceptable language, and Theodore Roosevelt once said, “The one absolutely certain way of bringing this nation to ruin or preventing all possibility of its continuing as a nation at all would be to permit it to become a tangle of squabbling nationalities. We have but one flag. We must also learn one language, and that language is English.”

Citing concerns that providing official documents and services in multiple languages would simply be too expensive, contemporary advocates of English-only legislation claim that mandating one language is one way to reduce the cost of government. Some proponents also believe that English-only laws encourage immigrants to assimilate by learning the official language of the United States. Opponents accuse the laws of being racist and suggest that supporters of English-only legislation are threatened by cultural diversity. Linguistic unity, they say, does not lead to political or cultural unity. Furthermore, providing official documents and services only in English in effect denies these services and information to those who do not understand English. Debates such as these bring up questions of the legal, social, and political status of minority groups and their languages, debates that exist in many countries besides the United States.

Today, most of those who wish to legislate English as the official language of the country target Spanish-speaking immigrants as the object of their concern. Language is often at the heart of the immigration debates that occur so often on the nightly news. Anxieties about being culturally “overwhelmed” by Spanish speakers who refuse to learn English culminate in claims that Latino immigrants are dividing the nation in two: one English-speaking and culturally “American,” and the other Spanish-speaking and unable to assimilate into the mainstream (see Patricia’s Notebook).

Historically, most immigrants to the United States sooner or later abandon their native tongues. As late as 1910, one out of every four Americans could speak some language other than English with the skill of a native; today that number is significantly lower. This was a result of the mass immigrations from Germany, Poland, Italy, Russia, China, and many other foreign lands. Much of this linguistic diversity has given way to English, partly because these other languages lacked legal status, partly because of the monolingual educational system in the United States, and partly because of social pressures.

Continuing the Debate

As this discussion illustrates, many cultures do not want to assimilate into English-speaking society, choosing instead to actively assert pride in their language. Keeping this in mind, consider these questions:

•Do you think the wave of immigrants today, with their pride in language, is different from earlier waves? How so?

•Will monoglot English speakers become a dwindling minority as more and more people become bilingual through either choice or necessity?

TEXTING AND LANGUAGE MODIFICATION

Though English may dominate the Internet (see Figure 4.11), much of what comes across our computer and cell phone screens isn’t a readily recognizable form of English. As with the diffusion of spoken English to far-flung regions of the British Empire, the English language that is spread via electronic correspondence is subject to significant modification. E-mailing, instant messaging, and text messaging Standard English on cell phones requires a lot of typing, and text is notoriously deficient in conveying emotions when compared to the spoken word. For these reasons, users often use abbreviations and symbols to shorten the number of keystrokes used, to add emotional punctuation to their correspondence, and to make electronic communication difficult to monitor by those who don’t understand the language—particularly parents and teachers!

English is an alphabetic writing system, where letters represent discrete sounds that must be strung together to form a word’s complete sound. A second major writing system is syllabic, where characters represent blocks of word sounds. This type of writing, prevalent throughout the Middle East and Southeast Asia, includes Arabic, Hebrew, Hindi, and Thai. The third form of writing is logographic, where characters represent entire words. Chinese is the only major language in this category.

156

English-speaking texters quickly learn to take shortcuts around the lengthiness inherent to alphabetic writing systems. The simplest and most commonly used shortcut involves using acronyms instead of whole words to convey common phrases. POS (parent over shoulder), VBG (very big grin), LOL (laughing out loud), and GMTA (great minds think alike) are some examples of this technique. Another shortcut involves using characters that sound like words. For example, the number “8” can substitute for the word or sound “ate,” so “h8” is “hate,” and “i 8” is “I ate.” In the first example, a syllabic approach to writing is used because “8” condenses the syllable “ate” into one character. Another technique involves using symbols to substitute for entire words. Using “8” for the word “ate” is an example of this technique, called rebus writing, where a symbol is used for what it sounds like as opposed to what it stands for. As your instructor for this class will likely confirm, such abbreviations and symbols have even worked their way into term papers at the college level, much to the consternation or delight of language scholars.

The use of symbols such as ![]() and

and ![]() , which are called pictograms, or word pictures, is similar to Chinese writing. Their popularity has resulted in a vast lexicon of pictograms as well as simpler symbol groupings, called emoticons, used to convey entire words, ideas, and emotions in a compact and often humorous form. Here are some examples:

, which are called pictograms, or word pictures, is similar to Chinese writing. Their popularity has resulted in a vast lexicon of pictograms as well as simpler symbol groupings, called emoticons, used to convey entire words, ideas, and emotions in a compact and often humorous form. Here are some examples:

|

:) |

(user is smiling or joking) |

|

:@ |

(user is screaming or cursing) |

|

:-# |

(well, shut my mouth!) |

Although the meaning of these symbols is understood by speakers of many languages because of their ubiquity, non-English languages also employ their own symbol combinations. In Korean, for instance, ^^ is used instead of :) to convey a smiling face and -_- is used instead of :( to depict a sad face. In Chinese, the number “5” is pronounced in a way that resembles crying, so “555” is the Chinese texter’s way of conveying sadness.

Spoken and written English are quickly picking up these cyberspeech patterns with expressions such as PITA, which is used to indicate that someone is a “pain in the ass” without actually saying so, and G2G, which is uttered instead of the marginally longer sounds “got to go” for which this acronym stands. As speakers of non-English languages become more heavily involved in texting-based activities, their spoken and written languages also doubtlessly will become modified.

LANGUAGE PROLIFERATION: ONE OR MANY?

Could all the world’s languages have derived from one single mother tongue? It may seem a large leap from the primordial tongue to a consideration of globalization and languages, but, in fact, the two are related. If we humans began with one language, why shouldn’t we return to that condition? If one language became 15,000 and the 7000 or so that remain will dwindle to 300 within a century, then why not end up with one again?

Are the forces of modernization working to produce, through cultural diffusion, a single world language? And if so, what will that language be? English? Worldwide, about 335 million people speak English as their mother tongue and perhaps another 350 million speak it well as a second, learned language. Adding other reasonably competent speakers who can “get by” in English, the world total reaches about 1.5 billion, more than for any other language. What’s more, the Internet is one of the most potent agents of diffusion, and its language, overwhelmingly, is English.

157

English earlier diffused widely with the British Empire and U.S. imperialism, and today it has become the de facto language of globalization. Consider the case of India, where the English language imposed by British rulers was retained (after independence) as the country’s language of business, government, and education. It provided some linguistic unity for India, which had 800 indigenous languages and dialects. This is why today many of India’s 1.2 billion people speak English well enough to provide customer support services over the telephone for clients in the United States. Even so, many people resent its use and wish India to be rid of this hated linguistic colonial legacy once and for all (see Figure 4.21). Although English is not likely to be driven out of India any time soon, it is true that the spoken English of India has drifted away from Standard British English. The same holds true for the English of Singapore, which is now a separate language called Singlish. Many other regional, English-based languages have developed—languages that could not be readily understood in London or Chicago.

But, is the diffusion of English to the entire world population likely? Will globalization and cultural diffusion produce one world language? Probably not. More likely, the world will ultimately be divided largely among 5 to 10 major languages.

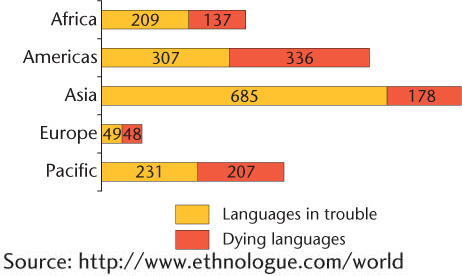

LANGUAGE AND CULTURAL SURVIVAL

Because language is the primary way of expressing culture, if a language dies out, there is a good chance that the culture of its speakers will, too. Languages, like animal species, are classified as endangered or extinct. Endangered languages are those that are not being taught to children by their parents and are not being used actively in everyday matters. Some linguists believe that more than half of the world’s roughly 7000 languages are endangered. Ethnologue, an online language resource (see Linguistic Geography on the Internet for this web site address), considers 377 languages to have become extinct since 1950, and another 906 to be on the “dying” list. Languages that have only a few elderly speakers still living fall into this category. The Americas and the Pacific regions together account for more than three-quarters of the world’s current nearly extinct languages, thanks to their many and varied indigenous language groups (Figure 4.13). For example, as of 2010, only five families in Argentina spoke Vilela; today, the language is classified as “dead,” with no remaining living speakers. When speakers die, it is most likely that their language will die out with them.

As Figure 4.13 shows, one-quarter of the world’s in trouble and dying languages may be found in the Americas. They represent a wealth of Native American languages slowly becoming suffocated by English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Other language hotspots—places with the most unique, misunderstood, or endangered tongues—are located around the globe (Figure 4.14). Three of the world’s most vulnerable regions are located in the United States.

language hotspots

Those places on Earth that are home to the most unique, misunderstood, or endangered languages.

158

Languages can also be used to keep cultural traditions alive by speaking them repeatedly. Keith Basso, an anthropologist who has written an intriguing book titled Wisdom Sits in Places, discusses the landscape of distinctive place-names used by the Western Apache of New Mexico. The people Basso studied use place-names to invoke stories that help the Western Apache remember their collective history. According to Nick Thompson, one of Basso’s interviewees, “White men need paper maps. . . . We have maps in our minds.” Thompson goes on to assert that calling up the names of places can guard against forgetting the correct way of living, or adopting the bad habits of white men, once Western Apaches move to other areas. “The names of all these places are good. They make you remember how to live right, so you want to replace yourself again.” One of the places Basso heard about is called Shades of Shit. Here is what he was told:

It happened here at Shades of Shit.

They had much corn, those people who lived here, and their relatives had only a little. They refused to share it. Their relatives begged them but still they refused to share it.

Then their relatives got angry and forced them to stay at home. They wouldn’t let them go anywhere, not even to defecate. So they had to do it at home. Their shades [shelters] filled up with it. There was more and more of it! It was very bad! Those people got sick and nearly died.

Then their relatives said, “You have brought this on yourselves. Now you live in shades of shit!” Finally, they agreed to share their corn.

It happened at Shades of Shit. (1996, p. 24)

Today, merely standing at this place or speaking its graphic name reminds the Western Apache that stinginess is a vice that can threaten the survival of the entire community.