GLOBALIZATION

5.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Discuss how globalization might variously deepen, reshape, or erase ethnicity, race, and racism.

The perception of differences among human groups, whether based in visible physical traits, cultural practices, language differences, or religion, is probably as old as human civilization itself. For at least a century, however, the demise of ethnic groups has been predicted. The idea of America as a melting pot has been used to describe the process by which the mixing of diverse peoples would eventually absorb everyone into one American mainstream culture. While the potent forces of globalization certainly play a role in this blending process, the fact that ethnic differences and racial strife still persist—and in some instances have worsened—points to their deeply rooted nature.

A LONG VIEW OF RACE AND ETHNICITY

In keeping with the notion that globalization is a process that has unfolded over several centuries, as opposed to only over the past 40 years or so, it is useful to look at global concepts of ethnicity and race in historical perspective. Long-standing cohesion through shared language, religion, or ethnicity provides group members with the perception of a common history and shared destiny—that deep feeling of “we-ness”—that is the basis of the modern nation-state. Israel’s identity as a Jewish nation, Turkey’s common language, and Japan’s distinctive cultural traditions set the stage for these groups to cohere as political entities.

Yet, all three of these nation-states harbor longstanding tensions among groups that reside within the national borders but who are not considered (or do not consider themselves) part of the cultural mainstream. They may not practice the official religion of the country, as in the case of Israel’s Palestinians, who are made up of Muslims and Christians. They may not speak the official language, as with Turkey’s Kurdish-speaking minority. Or, they may follow cultural traditions distinct from the mainstream, as is the case with Japan’s indigenous Ainu population.

Occupying a minority religious, linguistic, or ethnic position can expose a group to persecution. Violence against racial or ethnic minorities dates back to ancient times. The persecution of Jews, for example, began with pogroms, or widespread anti-Semitic rioting, during the Roman Empire some two millennia ago. Across medieval Europe, violence against Jews was episodic, occurring within Spain in the eleventh century, England in the twelfth century, Germany in the fourteenth century, and Russia in the nineteenth century. Anti-Semitic hate crimes still occur today throughout Europe and the United States. Yet, when Israel was founded in 1948 as the only nation-state to have Judaism as its official religion, non-Jewish minorities were, in turn, marginalized. Even minority Jewish populations, such as the Mizrahim (Arab) Jews residing in Israel, “are excluded and marginalized not only from social and political centers, but … from the very definition of what it is to be ‘Israeli,’” claims Israeli anthropologist Pnina Motzafi-Haller. Thus, it appears that no place or time is free of tensions based on ethnic or racialized difference.

201

RACE AND EUROPEAN COLONIZATION

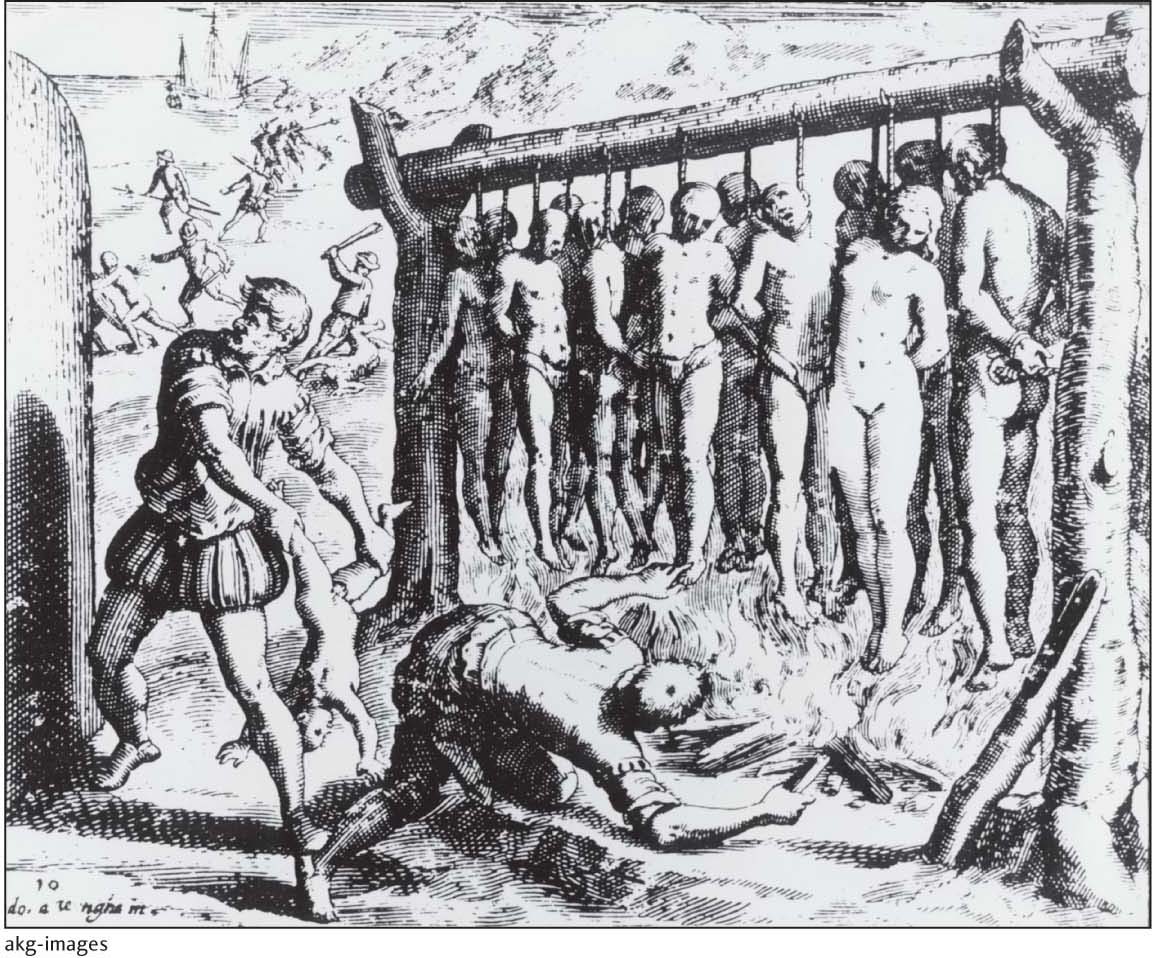

Europe’s colonization of vast territories in Africa, Asia, and Latin America was predicated on the drawing of sharp distinctions between the colonizers and the colonized. These distinctions were often depicted in racial terms. Indeed, conquered peoples were viewed as so different from Europeans that their very status as human beings was debated. The famous exchanges in the mid-sixteenth century between Caribbean-based Spanish priests and intellectuals in Spain is a case in point. Observing the abuses of indigenous populations firsthand led to an outcry by these clerics, who argued that the subjugated peoples were not animals and should not be subject to such treatment. “Are these not men? Have they not rational souls? Must you not love them as you love yourselves?” asked Antonio de Montesinos in 1511, in a sermon delivered on the island of Hispaniola (Figure 5.17). These same clerics, however, saw no problem with owning black slaves, simply because they did not view them as human beings.

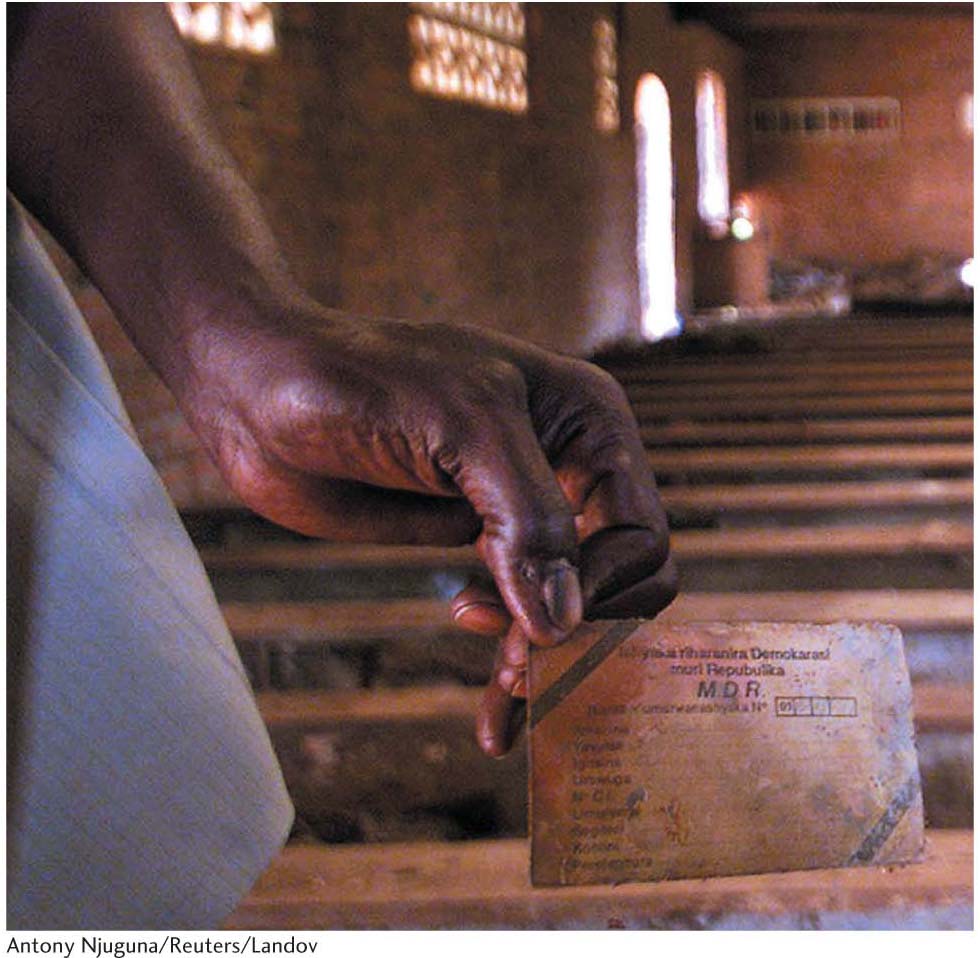

European colonialism frequently drew on existing ethnic and racial cleavages in colonized societies. Rwanda provides a tragic example of this practice. Rwanda is composed of two major ethnic groups: the Hutu, who, at 85 percent of the population, constitute the majority, and the minority Tutsi. Although differences in status have long existed between the two groups, it was not until the Belgian takeover of the territory in 1918 that the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi became racialized. Tutsis were given positions of power in the colonial government, educational system, and economic structure of colonial Rwanda under Belgian rule (Figure 5.18). Hutus’ physical differences from Tutsis were examined under a European racial lens. The shorter and darker Hutus were considered ugly, intellectually inferior, and natural slaves, whereas the taller, lighter Tutsis were extolled for their physical beauty and virtues of cultural refinement and leadership.

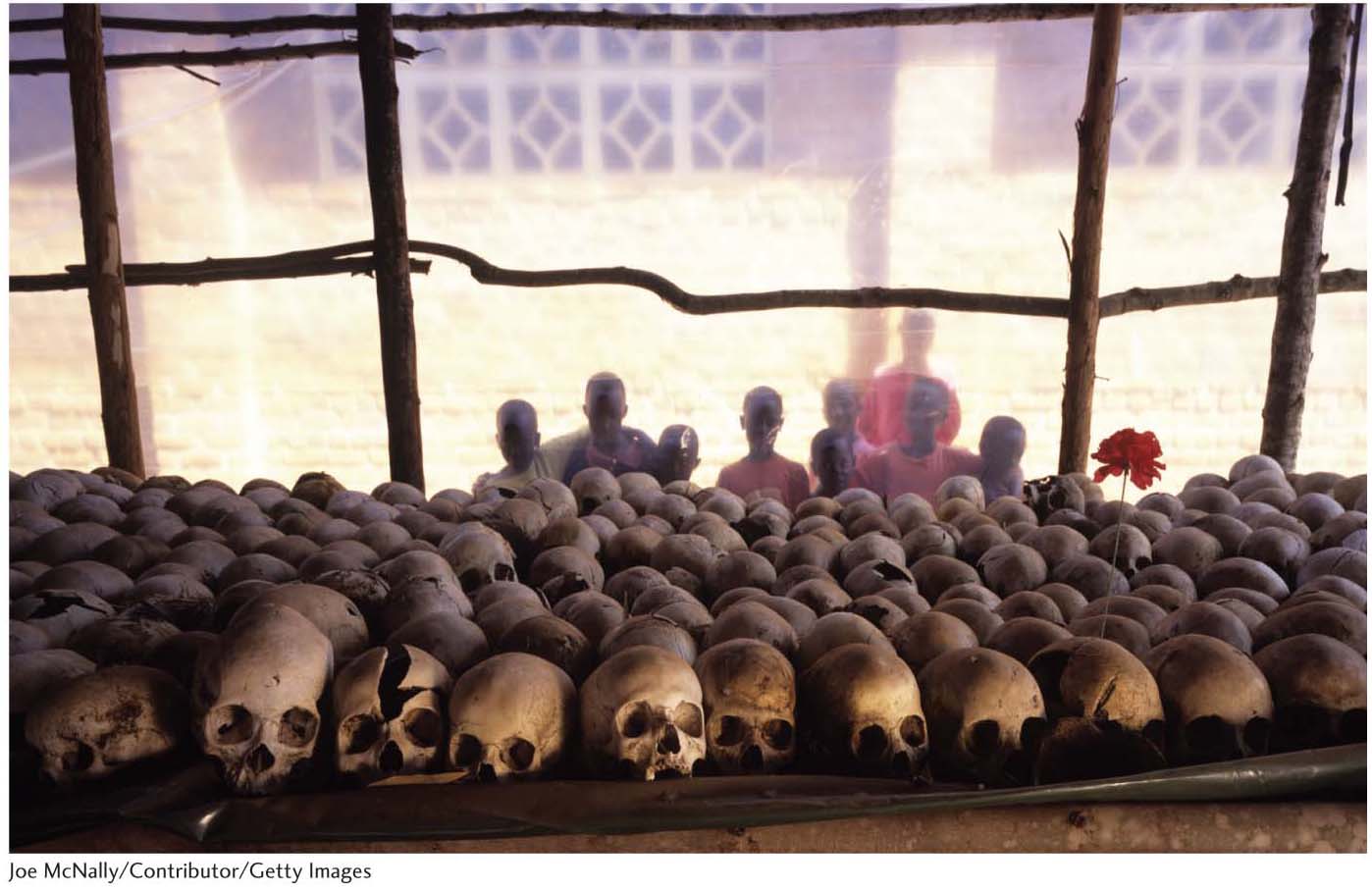

In 1959 the oppressed Hutu majority rebelled, leading to the deaths of some 20,000 Tutsis and the displacement of many more. Rwanda became independent from Belgium in 1961. Displaced Tutsi refugees regrouped in neighboring Uganda and in 1990 launched an invasion of Rwanda, demanding an end to racial discrimination and a reinstatement of their citizenship. Rapid deterioration of Hutu-Tutsi relations ensued, and plans to exterminate Tutsis and their Hutu sympathizers were promoted as the only way to rid Rwanda of its problems. In 1994 this genocide was conducted, resulting in the massacre of as many as 1 million people in the span of a few months (Figure 5.19).

genocide

The systematic killing of a racial, ethnic, religious, or linguistic group.

202

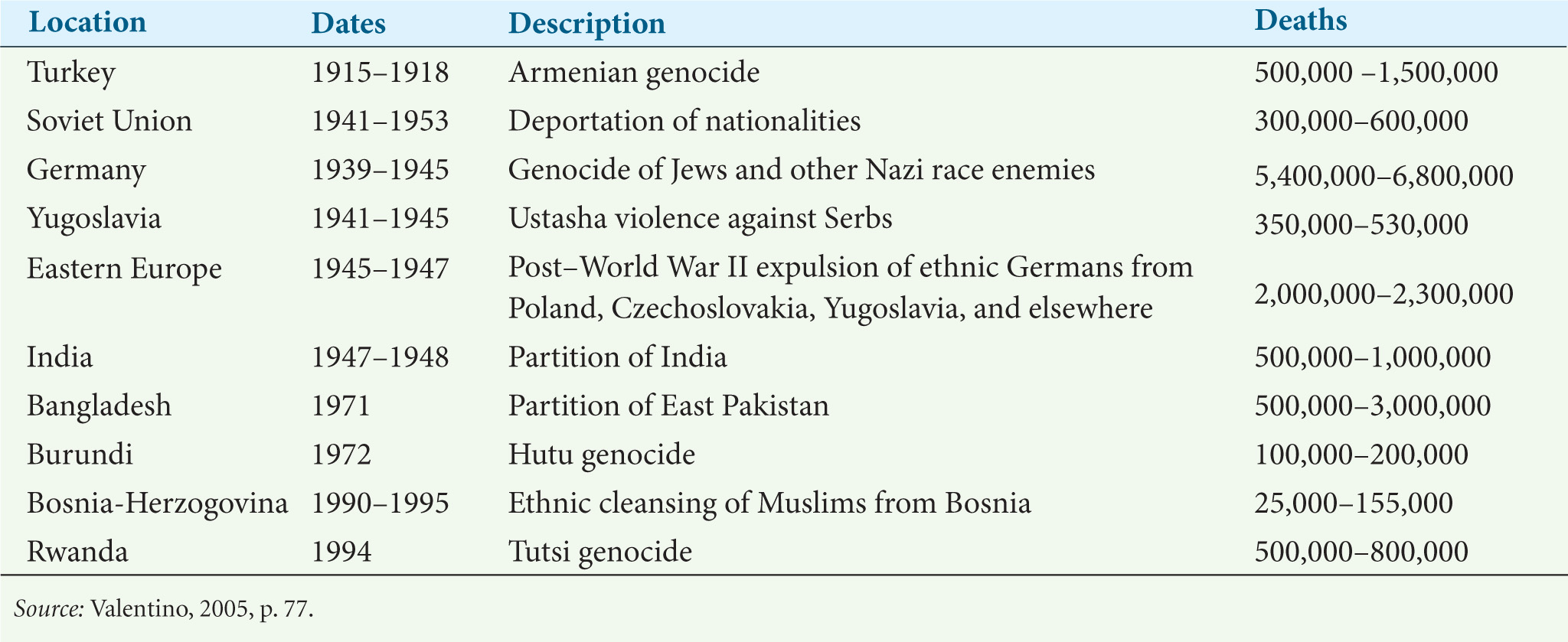

As these examples illustrate, ethnic and racial distinctions provided central features of European colonization and the rise of nation-states. Yet, as we have seen, tensions based on race and ethnicity predate the modern era. Racial and ethnic conflict is far from erased from the face of today’s global world (Table 5.3) and may, in fact, become aggravated as the bonds of the nation-state are loosened (see Subject to Debate).

INDIGENOUS AND MINORITY IDENTITIES IN THE FACE OF GLOBALIZATION

Differences do not always cause conflict, tension, and oppression. Indeed, pride in one’s ethnic or racial distinctiveness is common. Yet as revolutions in communications and transportation bring diverse peoples into heightened contact with one another the world over, distinctive markers of ethnicity come under pressure. Exposure to seductive U.S.-based cultural practices—in music, cuisine, fashion, lifestyles, and values—is thought to encourage people to shed their distinctive ways in favor of adopting a homogeneous modern, Westernized culture.

203

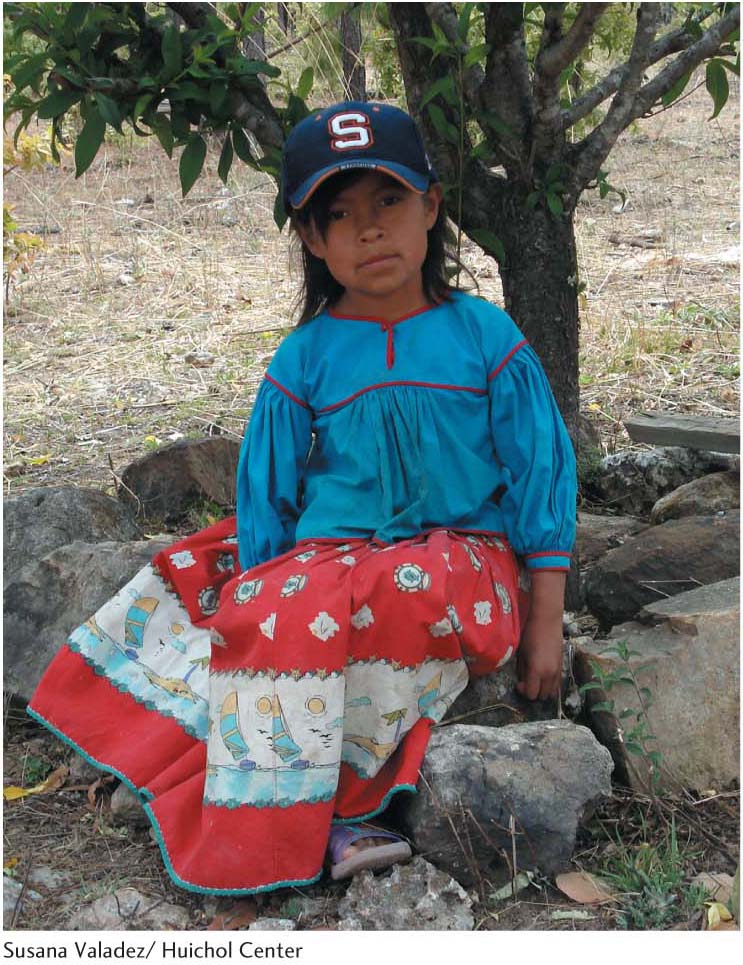

Late in the twentieth century, however, an ethnic resurgence, especially among indigenous groups, became evident in many countries around the world. In a very real way, many ethnic groups and their geographical territories have become bulwarks of resistance to globalization. Yet, it is too simplistic to romanticize indigenous groups as simply the keepers of ethnic distinctiveness in a globalizing world (Figure 5.20).

Members of indigenous groups must interpret the challenges as well as the opportunities offered by globalization and can be expected to modify their identities in complex ways.

204

Ethnic minority groups face similar pressures with respect to how their identities are asserted in majority society. This is particularly true of young people. Regardless of ethnicity, this age group is typically concerned with fitting in, which often involves hiding those aspects that mark them as “different” from the mainstream in some way. These concerns are heightened for ethnic minorities and immigrants, whose differences are often markedly apparent in language, dress, religion, and cuisine.

Take the example of Brazil’s Japanese population. Numbering around 1.5 million individuals, Brazil is home to the largest Japanese ancestry population outside of Japan. As we previously noted, Brazil was quite late in abolishing slavery in 1888—in fact, it was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to do so. Yet, the need for cheap agricultural labor remained, and in the first decade of the twentieth century, this labor began to be filled by immigrant Japanese. Fleeing poverty in their home country, Japanese immigrants worked Brazil’s coffee plantations. This migration reached a crescendo in 1931-1935 when over 70,000 Japanese immigrated to Brazil as a result of the strife of World War I. Around this time the Brazilian government attempted to force its immigrant populations from Germany, Italy, and Japan, as well as Jews, to “whiten” by assimilating into the mainstream through intermarriage and acculturation. They found the Japanese particularly resistant to such efforts, and by the 1970s these immigrants and their Brazilian-born descendants (Nikkeijin) formed a distinctive and economically well-off minority group (Figure 5.21).

Takeyuki Tsuda’s research on Brazil’s Nikkejin youth reveals the pressures faced by ethnic minorities. For example, these youths are often stereotyped in racial ways, as being smarter, politer, and neater than non-Japanese Brazilians. One father remarked, “When my son gets good grades in school, they say, ‘Of course, it’s because he’s Japanese.’ … When he keeps his desk clean in the classroom, they say, ‘Of course, he is Japanese.’” To complicate matters even further, many of these Brazilian-born youths and their parents have returned to Japan in order to take advantage of the economic opportunities now available there. When they arrive, these young people face considerable pressure to speak and act Japanese. According to one young man, “The Japanese make more demands on us than on whites or other foreigners in Japan because of our Japanese faces.” Tsuda found that many of these young people react by wearing Brazilian clothing, speaking Portuguese loudly in public, and in general acting “more Brazilian” than they ever did in Brazil, as ways of asserting their ethnic identity.

Globalization is far from a straightforward, one-way process when it comes to race, ethnicity, or any other aspect of human geography for that matter. Rather, globalization and its associated movements of people and ideas lead to highly complex geographies of race and ethnicity.

205