Melting Pot or Tapestry?

176

CHAPTER 5

GEOGRAPHIES OF RACE AND ETHNICITY

Melting Pot or Tapestry?

When does cuisine cease to be ethnic and become simply “American”? What roles do mobility and globalization play in the process?

Ethnic restaurants abound in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village neighborhood.

(Steve Lewis Stock/Getty Images.)

Go to “Seeing Geography” to learn more about this image.

177

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

▪5.1

Describe how ethnic groups are distributed geographically, and discuss how and why these distributions have changed over time.

▪5.2

Define the different types of migration.

▪5.3

Discuss how globalization might variously deepen, reshape, or erase ethnicity, race, and racism.

▪5.4

Analyze the diverse ways in which ethnic and racial groups interact with the natural environment, and discuss how these groups may be protected, or made more vulnerable.

▪5.5

Recognize the different ways that ethnicity and race leave imprints on the cultural landscape.

One of the enduring stories that the people of the United States proudly tell themselves is that “ours is an immigrant nation.” This story is on display during annual festivals celebrating the variety of ethnic traditions in countless cities, towns, and villages across the nation. For example, the midwestern town of Wilber, settled by Bohemian immigrants beginning about 1865, bills itself as “The Czech Capital of Nebraska” and annually invites visitors to attend a “National Czech Festival.” Celebrants are promised Czech foods, such as koláce, jaternice, poppy seed cake, and jelita; Czech folk dancing; Czech postcards and souvenirs imported from Europe; and handicraft items made by Nebraska Czechs (bearing an official seal and trademark to prove their authenticity). Thousands of visitors attend the festival each year. Without leaving Nebraska, these tourists can move on to “Norwegian Days” at Newman Grove, the “Greek Festival” at Bridgeport, the Danish “Grundlovs Fest” in Dannebrog, “German Heritage Days” at McCook, the “Swedish Festival” at Stromsburg, the “St. Patrick’s Day Celebration” at O’Neill, several Native American powwows, and assorted other ethnic celebrations (Figure 5.1).

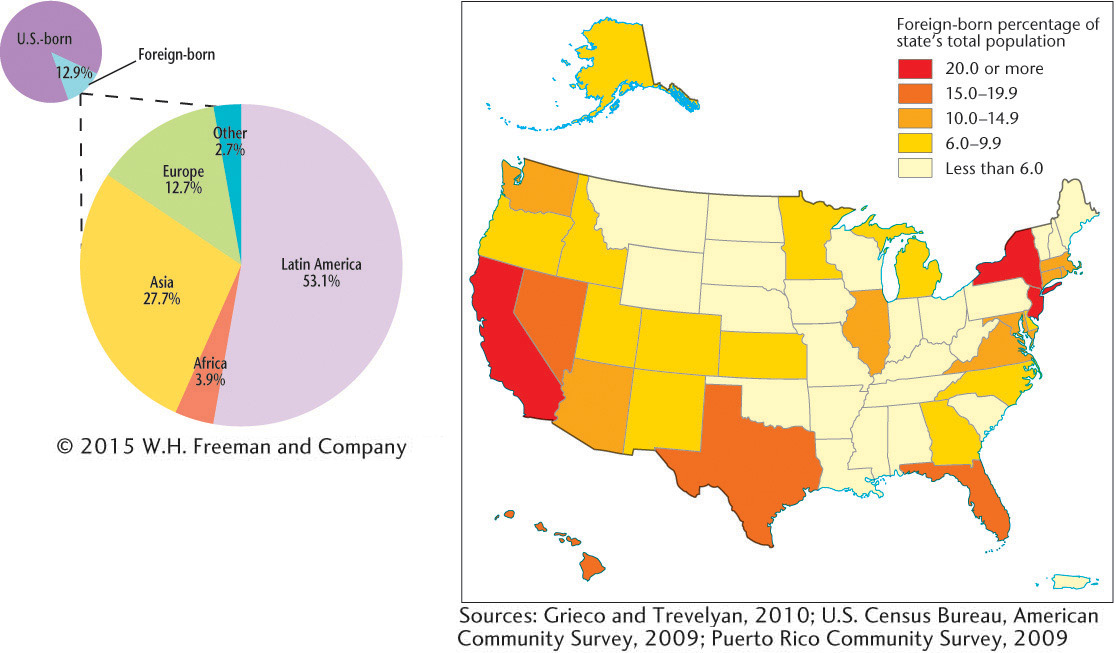

Today, Nebraska is still a magnet for immigrants, but since the 1990s, the state’s new arrivals have been overwhelmingly non-European. In particular, Mexican immigrants employed in Nebraska’s meat-processing industry find destinations such as Nebraska and other upper midwestern states attractive. In general, immigrants to the United States today are more likely to come from Asia or Latin America than from Europe, and they are changing the face of ethnicity in the United States (Figure 5.2). Indeed, ethnicity is a central aspect of the cultural geography of most places, forming one of the brightest motifs in the human tapestry.

178

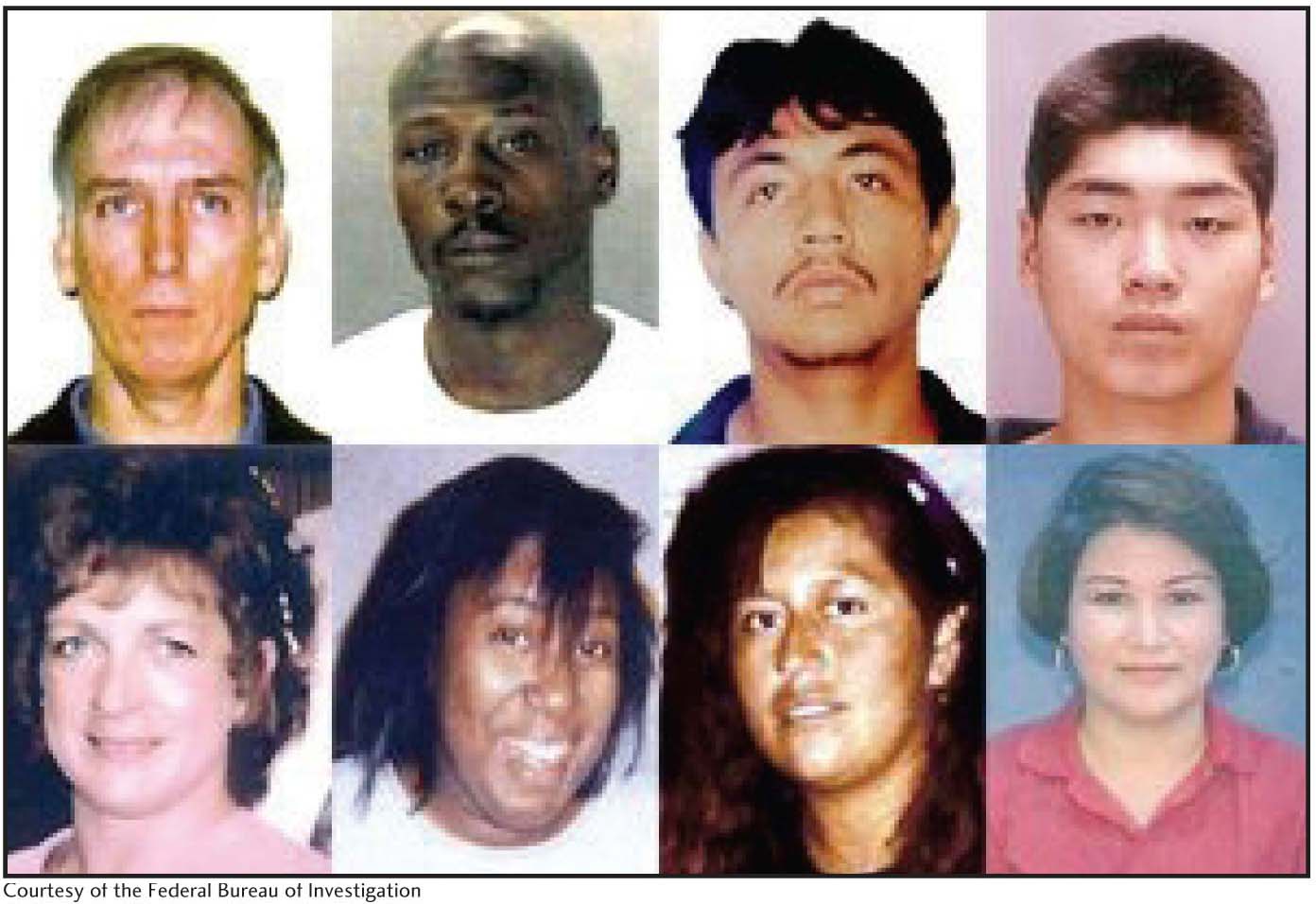

RACE OR ETHNICITY: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

Race is often used interchangeably with ethnicity, but the two terms have very different meanings, and one must be careful in choosing between them. Race can be understood as a genetically significant difference among human populations. A few biologists today support the view that human populations do form racially distinct groupings, arguing that race explains phenomena such as the susceptibility to certain diseases. In contrast, many social scientists (and many biologists as well) have noted the fluidity of definitions of race across time and space, suggesting that race is a social construct rather than a biological fact (Figure 5.3 and Figure 5.4).

race

A classification system that is sometimes understood as arising from genetically significant differences among human populations, or from visible differences in human physiognomy, or as a social construction that varies across time and space.

Because race is a social construction, it takes different forms in different places and times. In the United States, for example, the so-called one-drop rule meant that anyone with African American ancestry at all was considered black. This law was intended to prevent interracial marriage. It also meant that moving out of the category “black” was, and still is today, extremely difficult because one’s racial status is determined by ancestry. Yet, the notion that “black blood” somehow makes a person completely black is challenged by the growing numbers of young people with diverse racial backgrounds. The rise in interracial marriages in the United States, along with the fact that—for the first time in 2000—one could declare multiple races on the census form, means that more and more people identify themselves as “racially mixed” or “biracial” instead of feeling they must choose only one facet of their ancestry as their sole identity. Thus, golfer Tiger Woods calls himself a “Cablinasian” to describe his mixed Caucasian, black, American Indian, and Asian background. Race and ethnicity arise from multiple sources: your own definition of yourself; the way others see you; and the way society treats you, particularly in a legal context. All three of these are subject to change over time. Still, President Barack Obama, whose mixed-race ancestry has led him to identify with both his black and his white relatives, has struggled during his two terms in office with claims that he is at once “too black” and “not black enough” to be a representative president.

179

In Brazil, by contrast, a range of physiognomic features, such as skin pigmentation, eye color, and hair texture, are used to identify a person racially, with the result that many racial categories exist in Brazil. Siblings are frequently classified in significantly different racial terms depending on their appearance. The same person can be put into multiple racial categories by different people, and individuals’ own racial self-designations can depend on such variables as their mood at the time they are asked. Increased economic or educational status can “whiten” individuals formerly classified as black. However, one must keep in mind that Brazil was also the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery, and discrimination against darker-skinned Brazilians is still common today.

Studies of genetic variation have demonstrated that there is far more variability within so-called racial groups than between them, which has led most scholars to believe that all human beings are, genetically speaking, members of only one race: Homo sapiens sapiens. In fact, some social scientists have dropped the term race altogether in favor of ethnicity. This is not to say, however, that racism, the belief that human capabilities are determined by racial classification and that some races are superior to others, does not exist. In this chapter, we use the verb racialize to refer to the processes whereby these socially constructed differences are understood—usually, but not always, by the powerful majority—to be impervious to assimilation. Across the world, hatreds based in racism are at the root of the most incendiary conflicts imaginable (see Subject to Debate).

racism

The belief that human capabilities are determined by racial classification and that some races are superior to others.

180

What exactly is an ethnic group? The word ethnic is derived from the Greek word ethnos, meaning a “people” or “nation,” but that definition is too broad. For our purposes, an ethnic group consists of people of common ancestry and cultural tradition. A strong feeling of group identity characterizes ethnicity. Membership in an ethnic group is largely involuntary, in the sense that a person cannot simply decide to join; instead, he or she must be born into the group. In some cases, outsiders can join an ethnic group by marriage or adoption.

ethnic group

A group of people who share a common ancestry and cultural tradition, often living as a minority group in a larger society.

Different ethnic groups may base their identities on different traits. For some, such as Jews, ethnicity primarily means religion; for the Amish, it is both folk culture and religion; for Swiss Americans, it is national origin; for German Americans, it is ancestral language; for African Americans, it is a shared history stemming from slavery. Religion, language, folk culture, history, and place of origin can all help provide the basis of the sense of “we-ness” that underlies ethnicity.

181

Subject To Debate: RACISM: An Embarrassment of the Past, or Here to Stay?

Subject To Debate

RACISM: An Embarrassment of the Past, or Here to Stay?

Most modern societies are quick to claim that they have moved beyond the scourge of racism. Brazil, for example, bills itself as a “racial democracy.” Swedes see theirs as a nation that is particularly tolerant in matters of race. And in the “land of opportunity”—the United States— privileges are supposedly extended to all, regardless of race, creed, color, and so forth.

Yet, we know through our day-to-day experiences of studying, working, and socializing in specific places that although “post-racism” may be the ideal of modern societies, it is not always the fact in real life. In France in 2005, for instance, working-class Paris suburbs such as Clichy-sous-Bois—home to mostly Muslim immigrants from North Africa—became the site of rioting by youths who felt persecuted and excluded from French society because of their religion, culture, skin color, and immigrant status. A group of teenage boys who had been playing soccer were returning to the housing projects where they lived when they spotted the police. Thinking that they were being chased in relation to a reported burglary at a construction site, three of the teenagers hid in a power substation; two of them were accidentally electrocuted. This incident tapped into a well of unrest over what many see as the systematic exclusion in France of those with Arabic- or African-sounding names and darker skins, exclusion that has led to high levels of unemployment among banlieue (the French equivalent of a ghetto) residents. Months of rioting ensued throughout France.

The following year in the United States, widespread immigration protests filled city streets across the nation. In the spring of 2006, an estimated half a million people hit the streets of Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., and groups numbering in the tens of thousands marched in Denver, Milwaukee, Charlotte, Atlanta, Phoenix, and many other cities across the nation. Hispanics and their supporters took to the streets to protest legislation that threatened to deport undocumented workers and to classify anyone who helped an undocumented individual as a felon. As in the French incidents, Hispanic immigrants to the United States said they felt discriminated against and excluded from society. Even those who merely “look” or “sound” Hispanic are often the targets of racism. Rather than being violent terrorists or drains on society, protesters argued that Hispanics are, in fact, the backbone of low-wage labor in the United States.

These incidents highlight the fact that race-related tensions are about not only ancestry or skin pigmentation but also religious differences, immigration, and social opportunities. As anxieties arise over ever-higher levels of contact in a globalizing world, racialized intolerance is all too often the response. Indeed, A. Sivanandan has argued that “poverty is the new black” in a globalizing world that has become increasingly hostile toward involuntary migrants regardless of their skin color.

Continuing the Debate

Possible responses to racism lie along a continuum, from violent protest to waiting for time to erase racism. Consider these questions:

•Is racism really a serious problem, or are minority groups simply agitating as they always have?

•Will racism finally go away by itself as societies modernize and move beyond intolerance?

•Can legislation adequately and appropriately address the fundamental causes of racism, or are more radical measures—protests or work stoppages, for example—necessary given the deeply rooted nature of race-based discrimination?

182

As with race, ethnicity is a notion that is at once vexingly vague yet hugely powerful (see Patricia’s Notebook). The boundaries of ethnicity are often fuzzy and shift over time. Moreover, ethnicity often serves to mark minority groups as different, yet majority groups also have an ethnicity, which may be based on a common heritage, language, religion, or culture. Indeed, an important aspect of being a member of the majority is the ability to decide how, when, and even if one’s ethnicity forms an overt aspect of one’s identity. Finally, some scholars question whether ethnicity even exists as intrinsic qualities of a group, suggesting instead that the perception of ethnic difference arises only through contact and interaction.

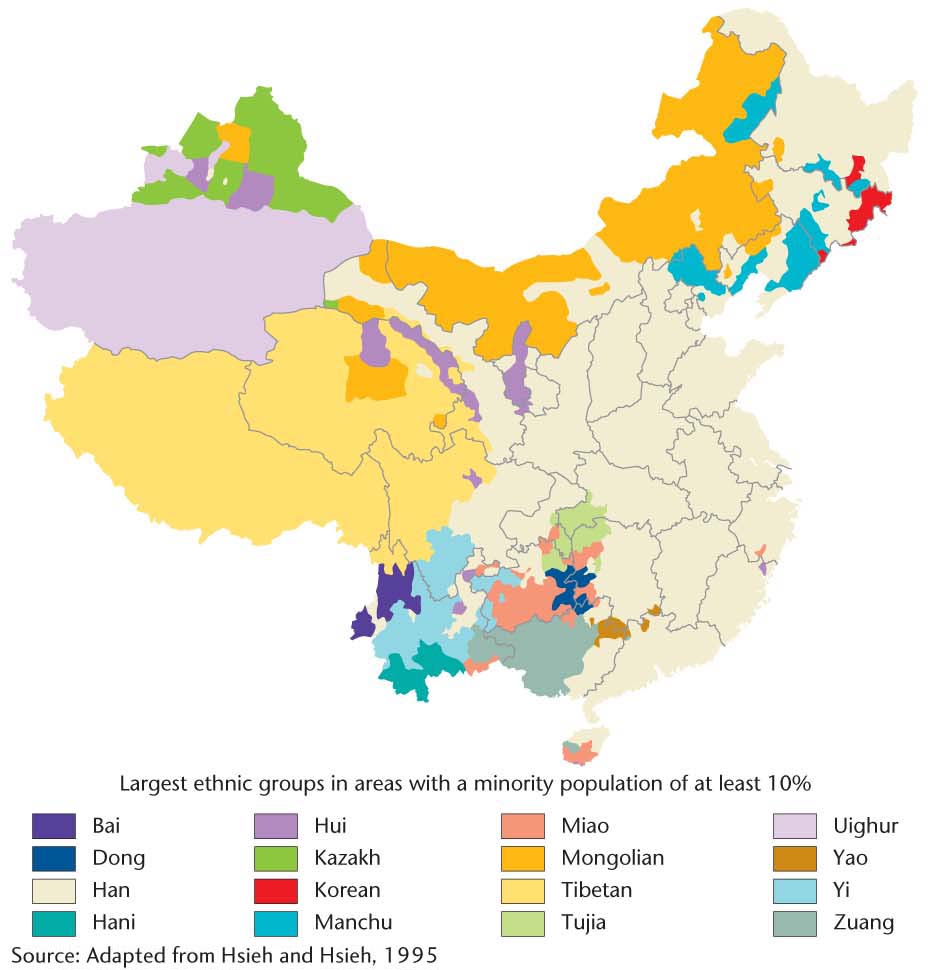

Apropos of this last point is the distinction between immigrant and indigenous (sometimes called aboriginal) groups. Many, if not most, ethnic groups around the world originated when they migrated from their native lands and settled in a new country. In their old home, they often belonged to the host culture and were not ethnic, but when they were transplanted by relocation diffusion to a foreign land, they simultaneously became a minority and ethnic. Han Chinese are not considered ethnic in China (Figure 5.5), but if they come to North America, they are. Indigenous ethnic groups that continue to live in their ancient homes become ethnic when they are absorbed into larger political states. The Navajo, for example, reside on their traditional and ancient lands and became ethnic only when the United States annexed their territory. The same is true of Mexicans, who, long resident in what is today the southwestern United States, found themselves labeled ethnic minorities when the border was moved northward after the 1848 U.S.-Mexican War. “We did not jump the border, the border jumped us!” is a common local comeback to this sudden shift in ethnic status.

183

184

This is not to say that ethnic minorities remain unchanged by their host culture. Acculturation often occurs, meaning that the ethnic group adopts enough of the ways of the host society to be able to function economically and socially. Stronger still is assimilation, which implies a complete blending with the host culture and may involve the loss of many distinctive ethnic traits. Intermarriage is perhaps the most effective way of encouraging assimilation. Many students of American culture long assumed that all ethnic groups would eventually be assimilated into the American melting pot, but relatively few have been; instead, they use acculturation as their way of survival. The past three decades, in fact, have witnessed a resurgence of ethnic identity across the globe (see Subject to Debate). Perhaps then transculturation, which is the notion that people adopt elements of other cultures as well as contributing elements of their own culture, thereby transforming both cultures, is a better way to view the interaction among cultures.

acculturation

An ethnic group’s adoption of enough of the ways of the host society to be able to function economically and socially.

assimilation

The complete blending of an ethnic group into the host society, resulting in the loss of all distinctive ethnic traits.

transculturation

The notion that people adopt elements of other cultures as well as contributing elements of their own culture, thereby transforming both cultures.

Ethnic geography is the study of the spatial aspects of ethnicity. Ethnic groups are the keepers of distinctive cultural traditions and the focal points of various kinds of social interaction. They are the basis of not only group identity but also friendships, marriage partners, recreational outlets, business success, and political power bases. These interactions can offer cultural security and reinforcement of tradition. Ethnic groups often practice unique adaptive strategies and usually occupy clearly defined areas, whether rural or urban. In other words, the study of ethnicity has built-in geographical dimensions. The geography of race is a related field of study that focuses on the spatial aspects of how race is socially constructed and negotiated. Cultural geographers who study race and ethnicity tend to always have an eye on the larger economic, political, environmental, and social power relations at work. This chapter draws on insights and examples from both ethnic geography and the geography of race.

Patricia’s Notebook: Teaching Race and Ethnicity

Patricia’s Notebook

Teaching Race and Ethnicity

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In my own research, I explore the changing geographies of race in the United States. In particular, I examine new immigration flows and cultural debates about immigration, race, and Latinos that have arisen in response. There is no question that Latino immigrants, particularly those who are poorest and brownest, are treated as a racial group in this country. True, the U.S. Census recognizes that “Latino” or “Hispanic” is an ethnicity and that those who identify as Latino or Hispanic can be of any (or mixed) race. But in practice most Americans, in their day-to-day engagement with race, view Latinos as one “point” in what David Hollinger has termed the ethno-racial pentagon: black, white, red, yellow, and brown.

We academics tend to teach what we research, and so I teach a great deal on race and ethnicity. Despite my affection for the topic, however, I’m the first to admit that it’s hard to think of a subject that is more controversial or more difficult to teach. Students are often angry or confused about race, based on their own, often bitter, experiences. Race and ethnicity are hard to define, and their borders seem to be perennially under siege. Are Hispanics a separate race? Can I change my ethnicity if I wish to do so? Is a meaningful conversation about race even possible? These are just some of the questions my students ask.

Regardless of these questions’ difficulty, it is important for students and professors to keep learning about and researching race and ethnicity. Racism is one of the most important social justice issues of our time. Avoiding candid discussions about racial and ethnic difference may make for a more congenial classroom climate in the short run, but it almost certainly stymies engagement that might constructively approach and transform the injustices of racism on our campuses, in our communities, and across the country.

Geography itself has been transformed thanks in part to our long and sometimes difficult conversations about race and other differences: sexuality, gender, and (dis)ability among them. Today, these differences are the subject of some of the most exciting research in the discipline, whereas 20 years ago there was little research if any at all on sexuality, gender, race and racism, and (dis)ability. Who geographers are has changed as well, and there are more “minority”—racial, sexual, physical.