CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

5.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Recognize the different ways that ethnicity and race leave imprints on the cultural landscape.

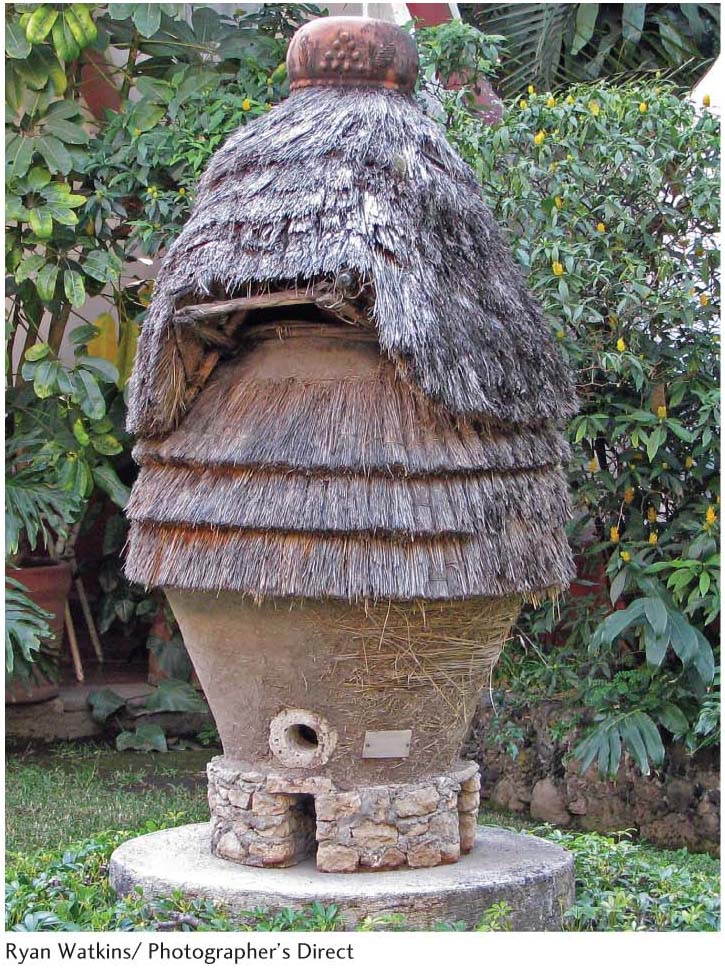

Ethnic and racialized landscapes often differ from mainstream landscapes in the styles of traditional architecture, in the patterns of surveying the land, in the distribution of houses and other buildings, and in the degree to which they “humanize” the land. Often the imprint is subtle, discernible only to those who pause and look closely. Sometimes it is quite striking, flaunted as an ethnic flag: a readily visible marker of ethnicity on the landscape that strikes even the untrained eye (Figure 5.26).

ethnic flag

A readily visible marker of ethnicity on the landscape.

210

Sometimes the distinctive markers of race and ethnicity are not visible at all but rather are audible, tactile, olfactory, or—as we explore shortly with culinary landscapes—tasty.

URBAN ETHNIC LANDSCAPES

Ethnic cultural landscapes often appear in urban settings. A fine example is the brightly colored exterior mural typically found in Mexican American ethnic neighborhoods in the southwestern United States (Figure 5.27). These began to appear in the 1960s in Southern California, and they exhibit influences rooted in both the Spanish and the indigenous cultures of Mexico. A wide variety of wall surfaces, from apartment house and store exteriors to bridge abutments, provide the space for this ethnic expression. The subjects portrayed are also wide-ranging, from religious motifs to political ideology, from statements about historical wrongs to those about urban zoning disputes. Often they are specific to the site, incorporating well-known elements of the local landscape and thus heightening the sense of place and ethnic “turf.” Inscriptions can be in either Spanish or English, but many Mexican murals do not contain a written message, relying instead on the sharpness of image and vividness of color to make an impression.

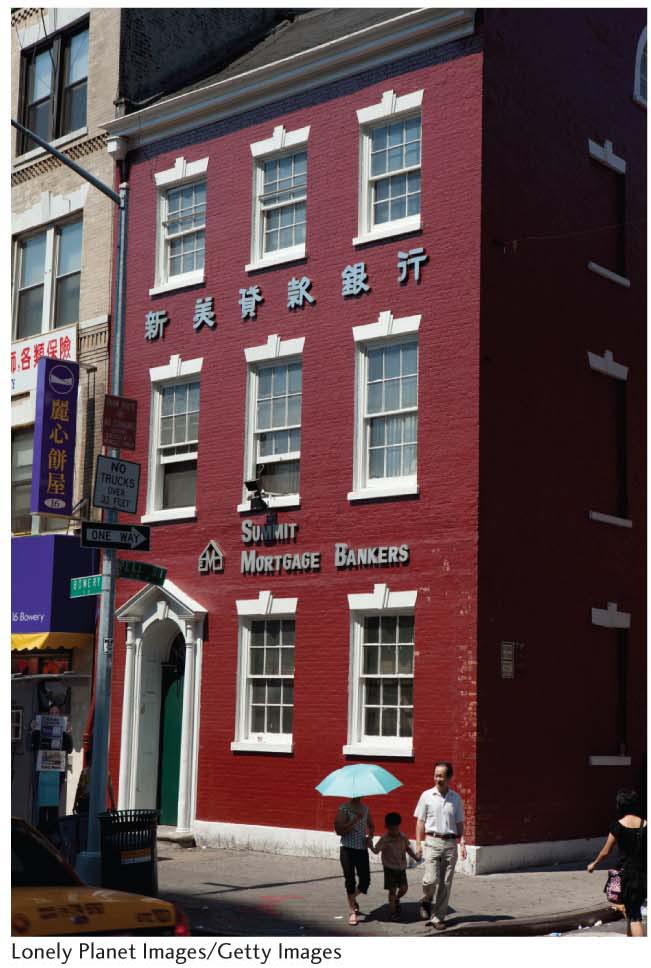

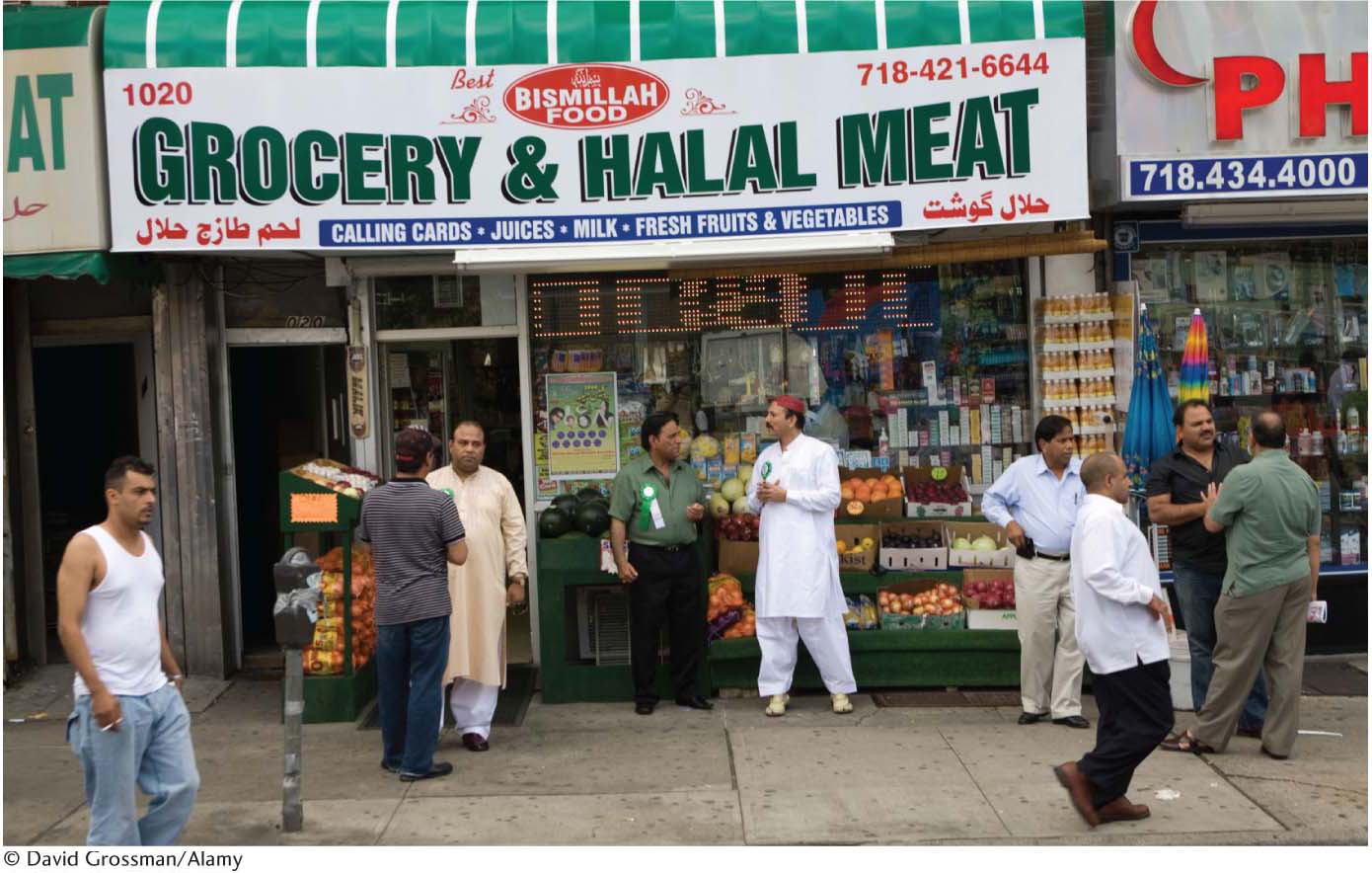

Usually, the visual ethnic expression is more subtle. Color alone can connote and reveal ethnicity to the trained eye. Red, for example, is a venerated and auspicious color to the Chinese, and when they established Chinatowns in Canadian and American cities, red surfaces proliferated (Figure 5.28). Light blue is a Greek ethnic color, derived from the flag of their ancestral country. Not only that, but Greeks also avoid red, which is perceived as the color of their ancient enemy, the Turks. Green, an Irish Catholic color, also finds favor in Muslim ethnic neighborhoods (Figure 5.29) in countries as far-flung as France and China because it is the sacred color of Islam (see Chapter 7).

211

Indeed, urban ethnic and racial landscapes are visible in cities across the world. This is true even when urban planners try their best to prevent the emergence of such landscapes. When Brazil’s capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasìlia in 1960, for example, very few pedestrian-friendly public spaces were incorporated into the urban plan of architects Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. Rather, residences were concentrated in high-rise apartments called superquadra; streets were designed for highspeed motor traffic only; and no smaller plazas, cafés, or sidewalks were included—all of which discouraged informal socialization (Figure 5.30). As historian James C. Scott notes in his discussion of Brasìlia, the lack of human-scale public gathering places was intentional. “Brasìlia was to be an exemplary city, a center that would transform the lives of the Brazilians who lived there—from their personal habits and household organization to their social lives, leisure, and work. The goal of making over Brazil and Brazilians necessarily implied a disdain for what Brazil had been.” But because the housing needs of those building the city and serving the government workers had not been planned, Brasìlia soon developed surrounding slums that did not follow an orderly layout. And because the desires of wealthier residents were not met by the uniform superquadra apartments, unplanned but luxurious residences and private clubs were also built. By 1980, 75 percent of Brasìlia’s population lived in unanticipated settlements. And because, as previously mentioned, Brazil’s social structure is, in part, based on skin pigmentation, it is the poorer and darker-skinned workers who live in the peripheral slums, whereas the wealthier and lighter-skinned residents tend to live in isolated enclaves for the rich. Thus, a racialized landscape of wealth and poverty emerged in Brasìlia despite all efforts to the contrary.

212

THE RE-CREATION OF ETHNIC CULTURAL LANDSCAPES

As mentioned previously in this chapter, migration is the principal way in which groups not ethnic in their homelands become ethnic or racialized, through relocation to a new place. As we have seen, ethnic groups may choose to relocate to places that remind them of their old homelands. Once there, they set about re-creating some—although, because of cultural simplification, not all—of their particular landscapes in their new homes.

Cuban immigrants, for example, have reconstructed in Miami aspects of their prerevolutionary Cuban homeland. In the early 1960s, the first wave of Cuban refugees came to the United States on the heels of Castro’s communist revolution on the island. Some went north, to places such as Union City, New Jersey, where today there is a sizable Cuban American population. Others, however, came (or eventually relocated) to Miami. Once a predominantly Jewish neighborhood called Riverside, what is today called the Little Havana neighborhood became the heart of early Cuban immigration. Shops along the main thoroughfare, Calle Ocho (or Southwest Eighth Street), reflect the Cuban origins of the residents: grocers such as Sedanos and La Roca cater to the Spanish-inspired culinary traditions of Cuba; cafés selling small cups of strong, sweet café Cubano exist on every block; and famed restaurants such as Versailles are social gathering points for Cuban Americans.

Because ethnicity and its expression on the landscape are fluid and ever-changing, the landscape of Calle Ocho reflects the current demographic changes under way in Little Havana. Although the neighborhood is still a Latino enclave, with a Hispanic population of over 95 percent, only half identify as “Cuban.” More than one-quarter of Little Havana’s residents are recent arrivals from Central American countries, particularly Nicaragua and Honduras, whereas more and more Argentineans and Colombians are arriving—like the Cubans before them—on the heels of political and economic chaos in their home countries. Today, you are just as likely to see a Nicaraguan fritanga restaurant as a Cuban coffee shop along Calle Ocho. This has prompted some to suggest that the neighborhood’s name be changed from Little Havana to the Latin Quarter (Figure 5.31).

Geographer Christopher Airriess has studied Vietnamese refugees in the United States. These refugees were initially brought to one of four reception centers, and then further relocated to rural and urban locations throughout the country, on the theory that spatial dispersal would hasten their assimilation into mainstream U.S. society. Airriess’s work reveals that a process of secondary, chain migration later led many of them to cluster in selected urban areas that offer warm weather and proximity to Vietnamese friends and relatives. Focusing on the Versailles neighborhood of New Orleans, Airriess found that the fact that the neighborhood is surrounded by swamps, canals, or bayous on three sides affords a degree of cultural isolation from other ethnic groups in the city. This has led to Versailles becoming an ethnic neighborhood where Vietnamese refugees re-create elements of their home landscape in the United States. The most prominent ethnic flag of the Vietnamese in Versailles is the vegetable gardens found on the perimeter of the neighborhood. Cultural preadaptation has led to the reproduction of Vietnamese rural landscapes here, sometimes with plants sent directly from Vietnam. It is the older Vietnamese who plant and tend the gardens. Such gardening provides a therapeutic activity, allows them to retain traditional dietary habits, enables them to produce folk medicines from plants, and reduces household food expenditures. Airriess notes that “the image of conical-hat-wearing gardeners leaning over plants within a multi-textured and moisture-soaked, vibrant green agricultural scene, coupled with frequent flyovers of military helicopters, is an eerie scene of wartime Vietnam reproduced.”

213

After Hurricane Katrina devastated sections of New Orleans—including Versailles (today more commonly called Village de L’est)—in 2005, the ethnic cultural landscape underwent a transformation. Many Vietnamese immigrants moved away from Versailles after the storm, whereas many Hispanics moved into the area, attracted by the many post-Katrina construction jobs. A 2006 survey found nearly 7000 Asians in New Orleans after Katrina, compared to nearly 12,000 before the storm. By contrast, Latinos have grown from about 14,000 before the hurricane to 16,000 post-Katrina: the only ethnic group, in fact, to have increased after 2005. Today, the commercial landscape reflects this transition. The first arrivals on the scene were the loncheras, or mobile lunch trucks (Figure 5.32). Then came the Hispanic-oriented restaurants, supermarkets, and services. At present, the remaining Vietnamese American residents are learning to adapt to the newcomers. Sara Catania recounts how Mai Thi Nguyen, a business development director in Village de L’est, reports that her aunt, a market owner, “is learning Spanish. She’s learning to say hello, how to tell customers how much something costs. It’s wild. I love it. It’s exciting.”

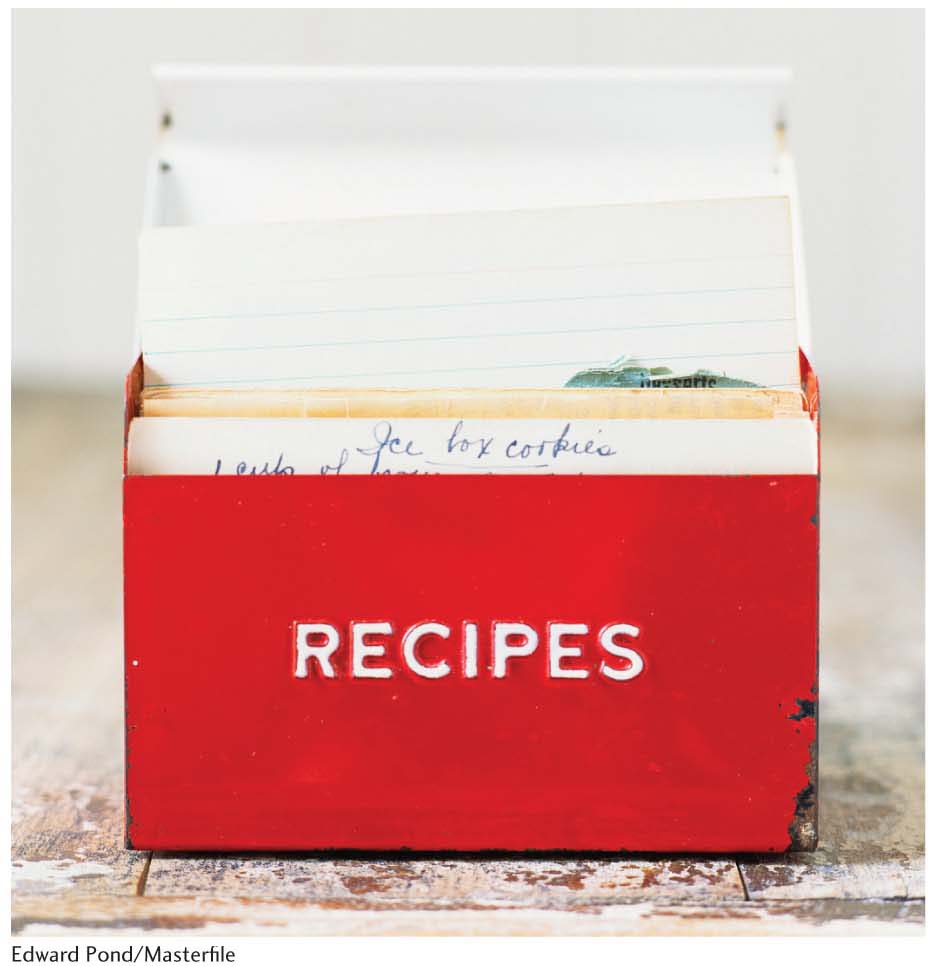

ETHNIC CULINARY LANDSCAPES

“Tell me what you eat, and I’ll tell you who you are.” This often quoted statement arises from the connections between identity and foodways, or the customary behaviors associated with food preparation and consumption that vary from place to place and from ethnic group to ethnic group (Figure 5.33). As geographers Barbara and James Shortridge point out, “Food is a sensitive indicator of identity and change.” Immigration, intermarriage, technological innovation, and the availability of certain ingredients mean that modifications and simplifications of traditional foods are inevitable over time. An examination of culinary cultural landscapes reveals that, although landscapes are typically understood to be visual entities, they can be constructed from the other four senses as well: touch, smell, sound, and—in this case—taste.

foodways

Customary behaviors associated with food preparation and consumption.

Although Singapore occupies the southern tip of the Malaysian Peninsula in extreme Southeast Asia, its cuisine draws heavily from southern Chinese cooking. This is because three-quarters of Singapore’s multiethnic population is of Chinese ancestry. Intermarriage between Chinese men, who came to Singapore as traders and settled there, and local Malay women resulted in a distinctive spicy cuisine called nonya. As we have already seen, there are far more ethnic Chinese in Asia than in other parts of the world, principally because of China’s proximity to other Asian countries.

214

The corn tortilla remains a staple of central Mexican foodways and is consumed at every meal by some families. But, many middle-class urban women in Mexico no longer have the time to soak, hull, and grind corn by hand to make corn tortillas from scratch. Rather, children are often sent every afternoon to the corner tortillería to purchase masa, or corn dough, or even hot stacks of the finished product. Convenience notwithstanding, old-timers complain that the uniform machine-made tortillas will never come close to the flavor and texture of a handmade tortilla. In some regions, notably in the northern part of Mexico and southern Texas, the labor-intensive corn tortilla was replaced altogether by wheat tortillas, which are much easier to make.

In the rural, mountainous Appalachian region of the eastern United States, distinct ethnic foodways persist and literally flavor this region. Geographer John Rehder observed that, during and after World War II, Appalachians maintained their cultural distinctiveness in the face of migration to northern cities in part through “care packages” of lard, dried beans, grits, cornmeal, and other foods unavailable in the North. Grocery stores in the Little Appalachia ethnic neighborhoods that formed in cities such as Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago soon began to cater to the distinct food preferences of the population. Thus, Appalachian foodways were maintained as Appalachians moved north.

Rehder tells of sending students on a scavenger hunt during a class field trip to Pikeville, Tennessee. To one young man, he handed a card that read, “What are cat head biscuits and sawmill gravy?”

About a half an hour later, my “biscuit man” returned with a scared look on his face and tears welling up in his eyes. I asked, “Where did you go and what happened?” He replied, “Well, … I … went to the feed store and asked an old man there, ‘What are cat head biscuits and sawmill gravy?’ just like you told me to do. Only the old man just growled at me and said, ‘Son, if you don’t know, HELL, I ain’t goin’ to tell you!’ And with that our lad left the feed store dejected and thoroughly upset. To calm him down, I said,” Why don’t you just go on down to the café. Get a little something to drink and maybe calmly run your question by them down there.” After a sufficient amount of time, I decided to go check on him. He was sitting on a red upholstered stool at the counter. As I drew closer, he looked up and, with fresh and quite different tears in his eyes, pointed to his plate: “This,” he said proudly, “is cat head biscuits and sawmill gravy!” (p. 208)

Rehder explains that cat head biscuits are flour biscuits made in the exact size and shape of a cat’s head and baked golden in a wood stove. Sawmill gravy is a southern-style white gravy made in a cast-iron skillet. Legend has it that the cook at the Little River Lumber Company logging camp ran out of flour for the gravy and substituted cornmeal. The loggers complained about the texture, referring to it as “sawmill gravy.” For further discussion of ethnicity and food, see Doing Geography and Seeing Geography.

215

DOING GEOGRAPHY

DOING GEOGRAPHY

Tracing Ethnic Foodways Through Recipes

At some point in our family histories, we all trace our roots back to migrants. Perhaps your ancestors walked here some 30,000 years ago. Perhaps they arrived on slave ships in the seventeenth century. Perhaps they were traders who settled and married locals. Were they part of the waves of Europeans in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries, or have you yourself only recently immigrated? More than likely, your ethnic inheritance results from a combination of different immigrant groups. As the geographer Doreen Massey wrote, “In one sense or another most places have been ‘meeting places’; even their ‘original inhabitants’ usually came from somewhere else.” In other words, if you dig into the history of any place, you’ll find layers upon layers of people arriving from other places and bringing their cultural baggage—recipes and all—with them.

For this exercise, you will analyze one of the most commonplace, yet revealing, items of ethnic geography: a recipe. Certainly, you are what you eat, but you also eat where you are, and the foodways in which you take an active part are very revealing of both who you are and where you are. Even though you may not be conscious of it, the simple act of cooking a meal sets into motion all sorts of cultural geography elements: regional identity, ethnic heritage, place-specific agricultural traditions, and so on. Together, these form important components of identity and place.

Steps to Analyzing a Recipe

Step 1:

Identify a recipe to analyze. Most of you grew up or are now living in households where meals are cooked on site at least some of the time. Choose a recipe that is used often and has been around for a while. The best candidate is a favorite family recipe that has been passed down through the generations (see the note below). If you don’t have a copy of the recipe, you will need to interview a person who does—if necessary, by phone or e-mail.

Step 2:

With a written recipe now in front of you, answer the following questions. You can interview someone in your family about this recipe, too.

■From where does this recipe come? With what country, or region, is it identified?

■Do any of the recipe’s ingredients give clues about the origins of the recipe? Do the ingredients draw on particular animal or plant ingredients that are, or were, produced where the recipe originated?

■Has the recipe been modified to substitute ingredients that are no longer available, either because the person who used the recipe migrated or because the ingredients went out of production?

■Are there ingredients used in the recipe that are identified with particular ethnic groups and perhaps aren’t consumed by others living in the same place?

■Do elements of the recipe’s preparation give additional clues about the foodways of the people who developed the recipe?

■Are there special occasions, such as holidays, when this recipe is always used?

■Do any of the ingredients or methods of preparation have symbolic meanings or stories associated with them?

In sharing the results of the recipe analysis, the class can list the various places and ethnicities that together comprise the foodways of the students. The class might want to organize a potluck meal where students share the dishes they have analyzed. Students may also create a cookbook of their recipes and map the places from which they come.

Note: If you are attending school in a foreign country, use a family recipe from your native homeland. E-mail or call a family member to discuss this recipe using the guidelines for this exercise. Also, some of you may have grown up in an institutional setting, where you consumed food prepared in a cafeteria. Institutional foods can be very revealing of local ethnic influences, so for this exercise choose a dish commonly prepared for the evening meal.

216

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

America’s Ethnic Foodscape

When does cuisine cease to be ethnic and become simply “American”? What roles do mobility and globalization play in the process?

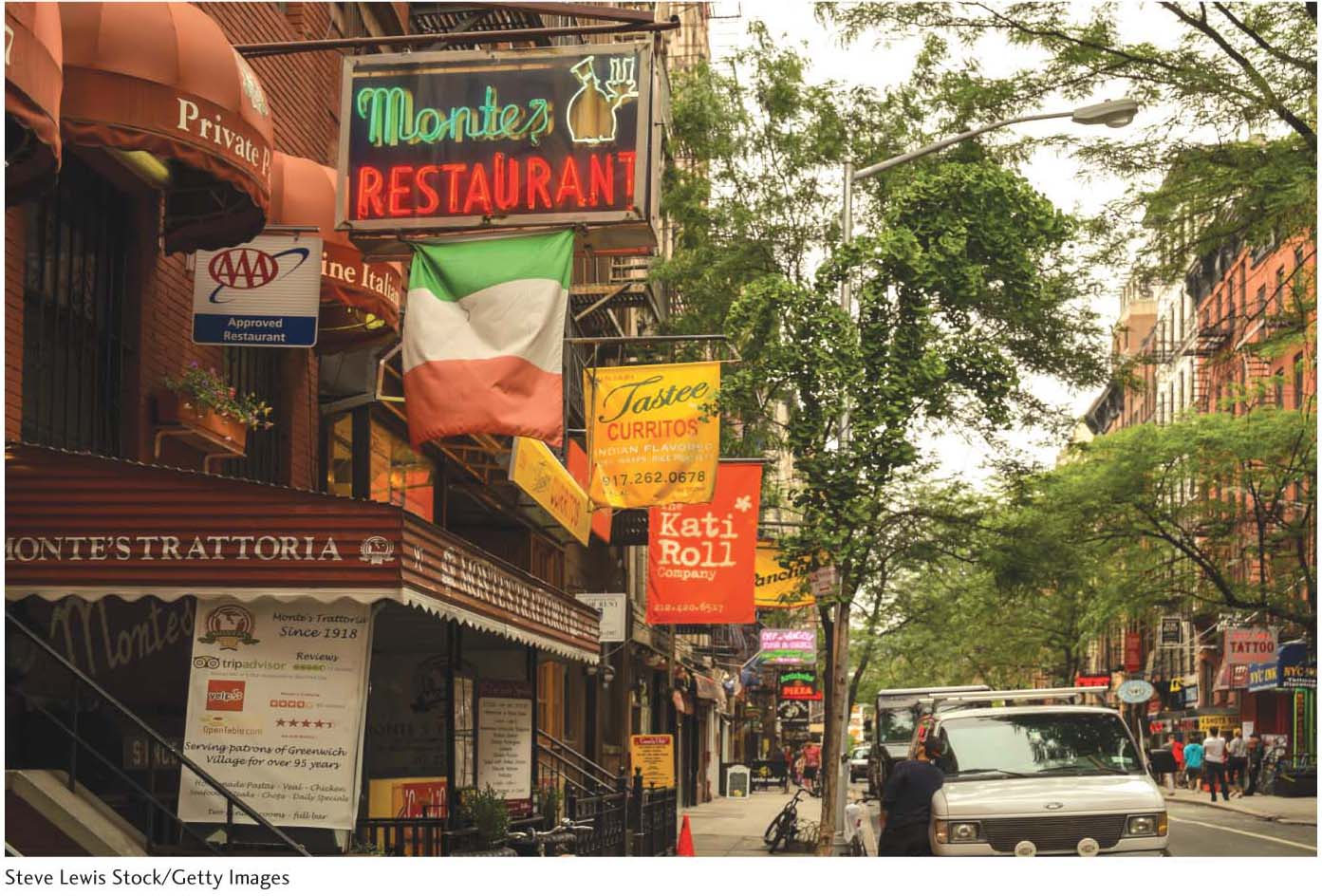

Ethnic restaurants abound in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village neighborhood.

(Steve Lewis Stock/Getty Images.)

This street scene was shot in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village neighborhood, but it could have just as easily been taken in any number of major U.S. urban areas. The signs display a mixture of ethnic foods: Pakistani (Tastee Curritos), Indian (Kati Roll), and Italian (Monte’s Trattoria) are the three most visible restaurants in the foreground of this photo.

As you know from Chapter 4, New York City is the most linguistically varied area on the face of the planet. This reflects the many and varied streams of immigration to this place. And with language comes food: two of the central aspects of ethnic identity. The ancestors of the owners of Monte’s Trattoria may well have arrived in the United States between 1890 and the mid-1920s, the peak years for Italian immigrants. The owners of Tastee Curritos and Kati Roll probably arrived almost a century later. Changes in U.S. immigration laws in 1965 abolished the previous national quota system for immigrants, which had the effect of greatly diversifying the immigrant stream as well as increasing the total numbers of immigrants to America. As you know from reading this chapter, the major areas sending immigrants to the United States are no longer Europe; rather, they are Asia and Latin America.

Cultural geographer Richard Pillsbury famously quipped that America has no foreign food because we have accepted every possible foreign cuisine and made it our own. Americans are for the most part very willing to consume foods from all over the globe, as this image shows. In addition, Tex-Mex, Asian fusion, and many “Chinese” dishes—among them, chop suey, General Tso’s chicken, and fortune cookies—are great examples of “foreign” cuisines that have been heavily Americanized, if not invented entirely in the United States.

So what exactly is “American” food, then? Perhaps the squash, beans, and corn consumed by Native Americans are our only example of a cuisine that is truly indigenous to the United States. Or, perhaps American fast food, which has itself diffused across the globe (along with the drive-in landscapes that accompany fast-food restaurants), is our only contemporary American food?

217

An Education in Equality

![]() An Education in Equality

An Education in Equality

This video profiles a young African American man, Idris Brewster, and his family over the course of his thirteen years at the Dalton Academy, an elite private college preparatory school in Manhattan. His mother is an immigrant of mixed-race Caribbean ancestry, while his father describes his past as one of economic deprivation. Both utilized education as a ticket to an upper-class lifestyle, and they want their son to use education to excel as well. Idris moves between elite and not-so-elite spaces in his daily life, and in the process he is forging his identity as a black man with a bright future in a world where race still matters.

Thinking Geographically:

This video explores the role of education, and its power to elevate an individual’s class status. What sorts of expectations, hopes, and pressures do Idris’s parents place on his shoulders? How does race matter in this regard?

Geographers and others who study race note that so-called micro-aggressions—the slight, everyday indignities directed at people of color that question their legitimacy to occupy certain roles and spaces—are prevalent in the lives of people such as Idris Brewster. Can you find examples of racial micro-aggressions in the video?

Idris Brewster appears to lead two lives: one as a student at an elite college prep school, and one as a young black man in Brooklyn. How do those two lives overlap, and what disconnects between them can you identify from the video?