Spaces and Places of Sacredness

270

CHAPTER 7

THE GEOGRAPHY OF RELIGION

Spaces and Places of Sacredness

How can an ordinary landscape, such as a parking lot, become a sacred space?

Parking lot shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe, Self-Help Graphics and Art, East Los Angeles.

(Courtesy of Patricia L. Price.)

Go to “Seeing Geography” to learn more about this image.

271

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

▪7.1

Define the differences among religions as well as the basic tenets of the world’s principal religions, and locate their primary regional expressions on a world map.

▪7.2

Discuss how and why the world’s religions became distributed as they are today.

▪7.3

Critically analyze how globalization has affected the practice of religion.

▪7.4

Discuss specific ways in which the natural environment shapes, and is shaped by, religious beliefs and practices.

▪7.5

Describe how religions have left their particular mark on the cultural landscape.

Religion is a core component of culture. For many, religion is the most profoundly felt dimension of their identities. For this reason, it is important to clearly state what is meant by the term and provide a sense of the many ways in which religion can be manifest in people’s lives. Religion can be defined as a more or less structured set of beliefs and practices through which people seek mental and physical harmony with the powers of the universe. The rituals of religion mark the events in our lives—birth, puberty, marriage, having children, and death—that are observed and celebrated. Religions often attempt not only to accommodate but also to influence the awesome forces of nature, life, and death. Religions help people make sense of their place in the world. In literal terms, the word religion—derived from the Latin religare—means “to fasten loose parts into a coherent whole.”

religion

A social system involving a set of beliefs and practices through which people seek harmony with the universe and attempt to influence the forces of nature, life, and death.

But religion goes beyond a merely pragmatic set of rules for dealing with life’s joys and sorrows. Most religions incorporate a sense of the supernatural that can be manifest in the concept of a God or gods who play a role in shaping human existence, in the notion of an afterlife that may involve a place of rest (or torment) for those who have died, or in ideas of a soul that exists apart from our physical bodies and that may be released, or even born again, once we have died. This sense of the otherworldly is often spatially demarcated through the designation of sacred spaces, such as cemeteries, religious buildings, and sites of encounters with the supernatural.

272

In addition, religion is often at the heart of how people with very different worldviews can come to understand one another. So, on the one hand, the conquest of the Americas by the Iberians (people of modern-day Spain and Portugal) was often a violent affair, whereby the religious conversion of indigenous peoples to Christianity accompanied the political takeover. Temples were destroyed and coercion was often used to convert the natives to Christianity. On the other hand, the Virgin of Guadalupe, said to have appeared to the indigenous Mexican convert Juan Diego in 1531—only 10 years after Cortes’s conquest of Mexico—is believed to be one of the most powerfully healing figures in the Americas to this day. Her portrait is a mixture of European and indigenous American symbols (Figure 7.1). In her kind manner of speaking to Juan Diego in Nahuatl (an indigenous language spoken by central Mexicans) and her resemblance to the earth goddess Tonantzín, she made sense to native Mexicans. For the Spaniards, dark-skinned virgins had long been part of their religious symbolism. In the midst of the violence of conquest, then, the Virgin of Guadalupe provided a mother figure that was readily acceptable to native Mexicans, was familiar to Spaniards, and acted as a bridge by which people from these two very different cultures could understand one another.

CLASSIFYING RELIGIONS

Each of the world’s major religions is organized according to more or less standardized practices and beliefs, and each is practiced in a similar fashion by millions, even billions, of adherents worldwide. Yet many people also express their religious faith in individual ways. Rituals and prayers can be adapted to fit particular circumstances or performed at home alone, or over the Internet. Some religions, including the Taoic religions of East Asia, as well as Hinduism and Buddhism, are largely individual or family-oriented practices. Some people do not observe a widely recognized religion at all. They may be secular, holding no religious beliefs, or express skepticism—even hostility—toward organized religion. They may consider themselves to be faithful but not follow an organized expression of their beliefs. Or they may practice an unconventional belief system, or cult. The term cult is often used in a pejorative sense because it conjures images of mind control, mass suicide, and extreme veneration of a human leader. It is important to keep in mind that the practitioners of belief systems falling outside of the mainstream—for example, Mormonism, Scientology, and even Alcoholics Anonymous—strongly object to being labeled cult members.

273

Different types of religion exist in the world. One way to classify them is to distinguish between proselytic and ethnic faiths. Proselytic religions, such as Christianity and Islam, actively seek new members and aim to convert all humankind. For this reason, they are sometimes also referred to as universalizing religions. They instruct their faithful to spread the Word to all the Earth using persuasion and sometimes violence to convert the “heathen.” The colonization of peoples and their lands is sometimes a result of the desire to convert them to the conqueror’s religion. By contrast, each ethnic religion is identified with a particular ethnic or tribal group and does not seek converts. Judaism provides an example. In the most basic sense, a Jew is anyone born of a Jewish mother. Though a person can convert to Judaism, it is a complex process that has traditionally been discouraged. Proselytic religions sometimes grow out of ethnic religions—the evolution of Christianity from its parent Judaism is a good example.

proselytic or universalizing religions

Religions that actively seek new members and aim to convert all humankind.

ethnic religion

A religion identified with a particular ethnic or tribal group; does not seek converts.

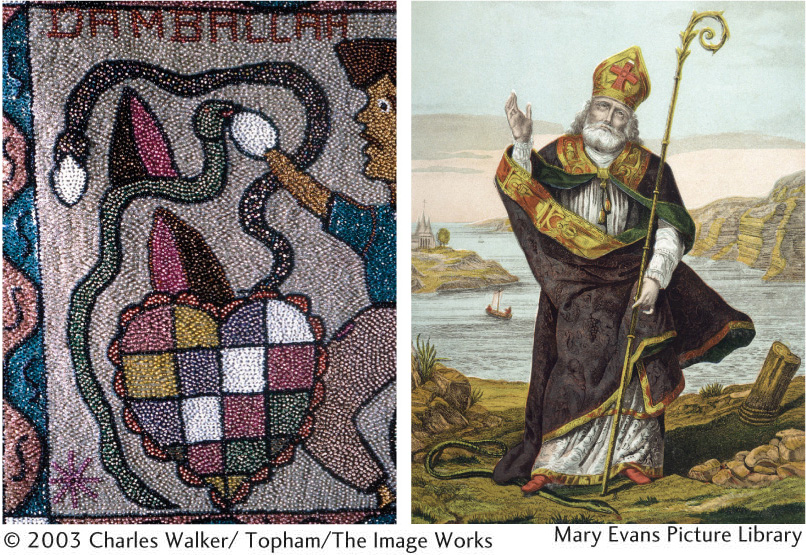

Another distinction among religions is the number of gods worshipped. Monotheistic religions, such as Islam and Christianity, believe in only one God and may expressly forbid the worship of other gods or spirits. Polytheistic religions believe there are many gods. For example, Vodun (also spelled Voudou in Haiti or Voodoo in the southern United States) is a West African religious tradition with adaptations in the Americas wherever the enslavement of Africans was once practiced. Although, as with most major religions, there is one supreme God, it is the hundreds of spirits, or iwa, that Vodun adherents turn to in times of need. Some of the better-known spirits in the Haitian Voudou tradition are Danbala Wedo, the peaceful snake-god who brings rain and fertility; Legba, the keeper of crossroads and doorways who is invoked at the beginning of all rituals; and Ezili Danto, the protective mother figure portrayed as a dark-skinned country woman.

monotheistic religion

The worship of only one God.

polytheistic religion

The worship of many gods.

Finally, the distinction between syncretism and orthodoxy is important. Syncretic religions combine elements of two or more different belief systems. Umbanda, a religion practiced in parts of Brazil, blends elements of Catholicism with a reverence for the souls of Indians, wise men, and historical Brazilian figures, along with a dash of nineteenth-century European spiritism, which is a set of beliefs about contacting spirits through mediums. Caribbean and Latin American religious practices often combine elements of European, African, and indigenous American religions. Sometimes, in order to continue practicing their religions, people in this region would hide statues of Afrocentric deities within images of Catholic saints. Or they would determine which Catholic figures were most like their own deities. Note in Figure 7.2 the comparison between Danbala, the snake-god of Haitian Voudou, with Saint Patrick, who is also associated with snakes. Orthodox religions, by contrast, emphasize purity of faith and are generally not open to blending with elements of other belief systems. The word orthodoxy comes from Greek and literally means “right” (ortho) “teaching” (doxy). Many religions, including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and Islam, have orthodox strains. So, for instance, although some orthodox Jews closely follow a strict interpretation of the Oral Torah (a specific version of the Jewish holy book), moderate but committed Jews may observe only some or perhaps none of the dietary, marriage, and worship proscriptions observed by orthodox Jews. Intolerance of other religions, or of those fellow believers not seeming to follow the “proper” ways, is associated with fundamentalism rather than orthodoxy. Many who consider themselves orthodox are, in fact, quite tolerant of other beliefs (see Subject to Debate on pages 280-281).

syncretic religions

Religions, or strands within religions, that combine elements of two or more belief systems.

orthodox religions

Strands within most major religions that emphasize purity of faith and are not open to blending with other religions.

fundamentalism

A movement to return to the founding principles of a religion, which can include literal interpretation of sacred texts, or the attempt to follow the ways of a religious founder as closely as possible.

274

The importance of religion to the contemporary study of cultural geography will be explored through our five themes. First, religious beliefs differ from one place to another, producing spatial variations that can be mapped as culture regions. Second, a high degree of mobility is characteristic of religions as they have spread historically through conquest, trade, and missionary activity. Violent conquests, diasporas, and the geographic expansion of religions through conversion have all played a role in shaping the contemporary world map of religious belief. Pilgrimages, too, illustrate how people can literally be set in motion through religion. Third, the global spread of religious beliefs has led to the reach of some religions, such as Hinduism, beyond their traditional hearths, whereas other religions, such as Judaism, have become diluted in part through migration-related diffusion. Religions, like all elements of cultural geography, must either adapt, or not, to the globalizing world. But religions influence globalization as well; here, we will consider the faith-based dimensions of the Internet. Fourth, the natural environment frequently plays an important part in faith-based belief structures, either because the forces of nature are viewed as potentially negotiable or because features of the natural landscape, such as rivers and mountains, are thought to exert a powerful influence over human destinies. Thus, the nature-culture dimension of religion is a key aspect of its cultural geography. Fifth, and finally, religious beliefs are often visible on the cultural landscape. For example, religious architecture, such as mosques, temples, and shrines, literally marks the landscape with the imprint of particular religious beliefs. How the spiritual shaping of some spaces as sacred comes to be is an important statement about what, and who, matters, culturally speaking.

275