CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Religion is firmly interwoven in the fabric of culture. Religions vary greatly from one region to another, creating diversity so profound as to give special significance to James Griffith’s admonition that we should all “learn, respect, and walk softly.” Yet religions tend to share some common elements, the most basic being that they provide a structure of faith that anchors communities. This religious spatial variation leads us to ask how these distributions came to be, a question best answered by examining methods of cultural diffusion. Some religions actively encourage their own diffusion through missionary activity or conquest. Other religions erect barriers to expansion diffusion by restricting membership to one particular ethnic group. People, as well, are set in motion thanks to spiritual practices, most notably pilgrimages.

In today’s globalizing world, it is worth exploring how—or even if—the world’s great religions will become significantly modified in response to changing contexts. The common practice of Internetbased religious practice brings into focus the debates over the importance of place in a global world.

The theme of nature-culture reveals some fundamental ties between religion and the physical environment. One major function of many religious systems, particularly the animistic faiths, is to appease and placate the forces of nature in order to achieve and maintain harmony between humans and the physical environment. Plants and animals diffuse—or not—with the spread of religions. The followers of various religions differ in their outlooks on environmental modification by humans.

The cultural landscape abounds with expressions of religious belief. Places of worship—mosques, temples, churches, megachurches, and shrines—differ in appearance, distinctiveness, prominence, and frequency of occurrence from one religious culture region to another. These buildings provide a visual index to the various faiths, as do their related architectural elements. Cemeteries and sacred spaces also add a special effect to the landscape that tells us about the religious character of the population. In all these ways, and more, the five themes of cultural geography prove relevant to the study of the world’s religions.

GEOGRAPHY @ WORK

Robert Szypko

First-Grade Teacher, Success Academy, Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York

Education:

BA Geography—Dartmouth College

Q. Why did you major in geography and decide to pursue a career related to the field?

A. I am fascinated by the ways that individuals negotiate cultural, social, and ethnic differences across space both in global and local (particularly urban) contexts. I initially chose geography because of the field’s strong tradition in development studies, but grew to love the larger analytical frameworks and technological skills emphasized in the discipline. I appreciate nuance, and the cultural geography courses I took brought my understanding of the nuances of culture, landscapes, and other topics to a new level. The more geography courses I took, the more I realized the breath of geography’s implications. Suddenly, my interests in music, education, graffiti, and journalism gained a greater richness as I saw them through a geographer’s lens.

Q. Please describe your job.

A. I lead a classroom of 25 first-grade students who come from a variety of neighborhoods across Brooklyn. My responsibilities include planning and executing lessons, analyzing and responding to classroom achievement data, and maintaining a positive and hard-working classroom culture. I work closely with parents to leverage them in the education of their children, and work to better understand the backgrounds and home lives of each student in order to best serve them in the classroom.

311

Q. How does your geographical background help you in your day-to-day work?

A. My geographical background has helped me more fully understand and account for my students’ varied backgrounds and the geographical diversity they represent (both in terms of where their family is from and where they live now, in different neighborhoods throughout Brooklyn). Geography’s emphasis on complexity when dealing with cultures and communities at any scale has given me the critical eye to maintain an open mind about parents, students, the neighborhood of my school, and so on. It has also helped me as I try to lead students toward a better understanding of the world around them. Children’s literature contains many different geographic representations, and I firmly believe that geographic nuance is important even at such a young age, from breaking down the homogenous identity of “Africa,” to developing a deep understanding of the different landscapes and cultures of the arctic zone.

Q. What advice do you have for students considering a career in the geography field?

A. Keep an open mind about what geography can do for you in your career. The critical thinking skills and technological skills (e.g., GIS) you acquire as a geographer can serve you well in a variety of industries and jobs.

A Chinese Threat to Afghan Buddhas

![]() A Chinese Threat to Afghan Buddhas

A Chinese Threat to Afghan Buddhas

Today, nearly everyone in Afghanistan practices Islam. But for around a millennium prior to the eighth century c.e., Buddhism was the prevalent religion. This video depicts the excavations of an ancient Buddhist settlement at a site called Mes Aynak, located southeast of the capital city of Kabul. Archaeologists’ work has been accelerated by the threat of destruction of the site at the hands of a Chinese mining company. Directly under this site lies a rich deposit of copper, which the company—and the government of Afghanistan—would like to access. Previously, in 2001, the so-called Buddhas of Bamiyan—also located in Afghanistan but not at Mes Aynak—were blown up by the Taliban (a fundamentalist Islamic political group in Afghanistan) who declared them to be idols. The Buddhas of Bamiyan, which dated from the sixth century c.e. and consisted of two large statues carved into a cliff, were a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The case study depicted in the video brings up the tensions often inherent at the crossroads of politics, religion, and economic development.

Thinking Geographically:

Find Afghanistan on a map. What is it about Afghanistan’s location and physical geography that have, historically speaking, made it so susceptible to religious change?

Afghanistan’s Buddhist cultural heritage seems to be under attack, first by the Taliban and now by a Chinese mining company. What arguments might the Taliban and Chinese mining company give to rationalize the destruction? What will be lost if the archaeological remains depicted in this video are destroyed? Is the loss Afghanistan’s alone?

Describe some specific ways in which the case study in this video can also be understood in the context of Chapter 4 (geography of language), Chapter 6 (political geography), Chapter 9 (development geography), and Chapter 10 (urban geography). Why is it that religion has so many connections to the rest of our lives?

312

DOING GEOGRAPHY

DOING GEOGRAPHY

The Making of Sacred Spaces

For this exercise, you will use Professor Kenneth Foote’s ideas about how spaces become sacred. In his book Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy, Foote argues that what a society chooses to forget about its past is at least as important as what it remembers in shaping an image of itself that can be presented to the world. Foote discusses how certain places in the United States have, or have not, become sacred sites. He notes, for example, that the battlefields of the Revolutionary and Civil wars are well marked and visited by thousands every year. Yet the 1692 execution site of the supposed witches of Salem, Massachusetts, is unmarked. How could the exact site of such an infamous event in U.S. history be impossible to locate? Foote realized that this scenario was not limited to the United States, writing, “Indeed, soon after my first trip to Salem, I found myself in Berlin before the reunification of Germany. There I came across similar places—Nazi sites such as the Gestapo headquarters and Reich chancellery—that have lain vacant since just after World War II and seem to be scarred permanently by shame.”

Professor Foote suggests that sites of important events can be sanctified, obliterated, purposely ignored, or fall somewhere in between. Sanctified sites are set apart from other sites, are carefully maintained, are often publicly owned, and attract annual visitors and ceremonies. At the other end of the spectrum, the sites of particularly shameful, stigmatized, or violent events simply may be obliterated from the landscape in an attempt to forget about them.

Steps to Understanding Sacred Spaces

Step 1:

Think about sites near where you now live and where a violent or tragic event occurred, for example, a murder, a freak accident, a natural disaster, an assassination, an act of terrorism, or a heinous crime. Virtually all places experience some such event. If nothing readily comes to mind, inquire, and inevitably you will discover an example for this exercise, even if you live in a rural area or a college town.

Step 2:

Once you have identified a site, consider its current status. Is it sanctified, is it obliterated, or does it fall somewhere in between? Elements of the landscape, such as signs or monuments (or the lack of them), will indicate the status of the site.

Step 3:

Take note of any debates surrounding what to do with this site. Has the status of the site changed over time? How?

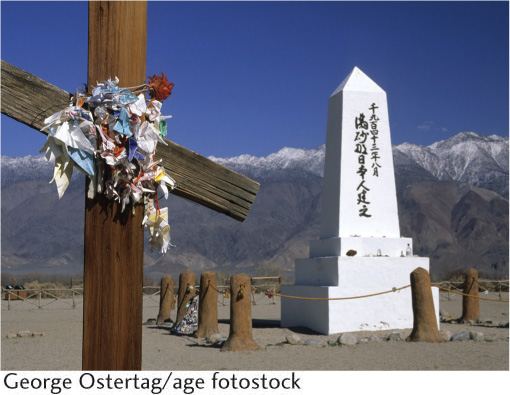

When people are unsure of how an event fits into their history, the site where the event occurred may inhabit a sort of limbo, remaining unmarked until the society in question comes to terms with the event. This is the case with many sites of racially motivated, violent, or shameful acts in the United States, such as the Memphis, Tennessee, motel where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, or the Manzanar, California, internment camp where Japanese Americans were confined during World War II. Only recently have both sites become prominent on the landscape after decades of neglect. Consider the following questions:

■Are any newsworthy events happening now that may mark a place as a site of tragedy?

■What sites, whether nearby or far away, do you expect to become more sacred over time?

■Can you think of an event that is so horrific that the place where it occurred will be forever forgotten and erased from the map?

313

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

Parking Lot Shrine

How can an ordinary landscape, such as a parking lot, become a sacred space?

Parking lot shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe, Self-Help Graphics and Art, East Los Angeles.

(Courtesy of Patricia L. Price.)

This large statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe inhabits the corner of the parking lot of Self-Help Graphics and Art, an artists’ cooperative in East Los Angeles. According to Michael Amezcua, a metalwork artist at Self-Help, neighborhood residents actively use this shrine, leaving offerings and petitions to the Virgin in the outdoor grotto. Every December 12th, neighborhood residents gather here to celebrate the feast day of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

We could interpret this unique parking lot shrine to be a variation on the yard shrine, a common feature of the residential landscape of the southwestern United States. Throughout the Mexican American homeland of the Southwest, it is common to see a small shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe in people’s front yards. This, in turn, is a variation on the Mexican custom of maintaining elaborate shrines and altars to important religious figures. These are sometimes located inside the house in a space reserved especially for altars (called a nicho). Or they can be located outside the house, near the front door, because Mexican homes usually do not have yard space in front of the house. On December 12th, altars all over Mexico and Mexican American areas in the United States are elaborately decorated with candles, ribbons, and flowers. Devotees of the Virgin of Guadalupe celebrate with family and neighbors throughout the night. Since turquoise blue is considered to be the favorite color of the Virgin of Guadalupe, this color abounds. Because the Virgin of Guadalupe is also the official patron saint of Mexico, the red, white, and green of the Mexican flag are prevalent in altar decorations.

In Miami, another Latino population center in the United States, yard shrines are built to La Virgen de la Caridad de Cobre. Like the Virgin of Guadalupe, La Virgen de la Caridad is an American manifestation of the Virgin Mary. This Virgin hails from the copper mining village of Cobre, in Cuba. She is believed to protect seafarers and has been adopted by Cuban rafters as their patron saint. Yemayá, who is an orisha, or spirit, in the Afrocentric Cuban religious tradition of Santería, is often equated with La Virgen de la Caridad de Cobre, as both are associated with the sea.

What does the fact that this particular shrine is built in a parking lot rather than a yard say about what, and how, spaces become sacred? Can you think of a more mundane place than a parking lot for such a hallowed figure as the Virgin of Guadalupe?Perhaps the drive-through architecture of strip malls, highways, and parking lots that is so closely associated with the urban landscape of Los Angeles has something to do with it. Where else, other than in Los Angeles, would you find a sacred parking lot?

314

Chapter 7 LEARNING OBJECTIVES REEXAMINED

Chapter 7

LEARNING OBJECTIVES REEXAMINED

7.1

Define the differences among religions as well as the basic tenets of the world’s principal religions, and locate their primary regional locations on a world map.

Review Figure 7.3. Where are the largest concentrations of Muslim, Jewish, and Christians located in the world?

7.2

Discuss how and why the world’s religions became distributed as they are today.

Explain what contact conversion means. What role does this term play in the distribution of the world’s religions?

7.3

Critically analyze how globalization has affected the practice of religion.

What role has the Internet played in the globalization of religion?

7.4

Discuss specific ways in which the natural environment shapes, and is shaped by, religious beliefs and practices.

Explain the term ecotheology. What role does ecotheology play in Christianity?

7.5

Describe how religions have left their particular mark on the cultural landscape.

What role do sacred spaces play in the cultural landscape?

KEY TERMS

Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

adaptive strategy animists contact conversion culture hearth ecotheology ethnic religion fundamentalism Gaia hypothesis megachurch monotheistic religion orthodox religions pilgrimages polytheistic religion proselytic religions religion sacred spaces syncretic religions universalizing religions | Religions that actively seek new members and aim to convert all humankind. Journeys to places of religious importance. The worship of only one god. A social system involving a set of beliefs and practices through which people seek harmony with the universe and attempt to influence the forces of nature, life, and death. Strands within most major religions that emphasize purity of faith and are not open to blending with other religions. Adherents of animism, the idea that souls or spirits exist not only in humans but also in animals, plants, rocks, natural phenomena such as thunder, geographic features such as mountains or rivers, or other entities of the natural environment. Large Protestant church structures, usually located in suburban areas of the United States, that have large congregations (2000-10,000 members) and utilize business models to tailor their spaces and services to their congregations' needs. Also called proselytic religions, they expand through active conversion of new members and aim to encompass all of humankind. A focused geographic area where important innovations are born and from which they spread. Religions, or strands within religions, that combine elements of two or more belief systems. A movement to return to the founding principles of a religion, which can include literal interpretation of sacred texts, or the attempt to follow the ways of a religious founder as closely as possible. Areas recognized by a religious group as worthy of devotion, loyalty, esteem, or fear to the extent that they become sought out, avoided, inaccessible to nonbelievers, and/or removed from economic use. The unique way in which each culture uses its particular physical environment; those aspects of culture that serve to provide the necessities of life—food, clothing, shelter, and defense. The worship of many gods. Spread of religious beliefs by personal contact. The theory that there is one interacting planetary ecosystem, Gaia, that includes all living things and the land, waters, and atmosphere in which they live; further, that Gaia functions almost as a living organism, acting to control deviations in climate and to correct chemical imbalances, so as to preserve Earth as a living planet. The study of the influence of religious belief on habitat modification. A religion identified with a particular ethnic or tribal group; does not seek converts. |

Geography of Religion on the Internet

You can learn more about the geography of religion on the Internet at the following web sites:

Get Religion

Founded because (quoting journalist William Schneider) “the press . . . just doesn’t get religion,” this blog attempts to ferret out the ghosts lurking in news coverage of religion.

History of Religion

“See 5000 years of religion in 90 seconds” by launching this dynamic map. The timeline shows major developments in the history of world religions.

National Religious Partnership for the Environment

An interfaith partnership encouraging environmental conservation in the name of religion.

Our Lady of Guadalupe

On the “ora pro nobis” (“pray for us”) section of this web site, you can post your prayer or request to the Virgin of Guadalupe and read the heartfelt posts of other devotees.

Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

Seeking to promote a greater understanding of the intersection between religion and public affairs, the Pew Forum conducts polls, surveys, and demographic analysis in the United States and around the world.

Sources

BBC News Europe. 2011. Halal and Kosher Hit by Dutch Ban. 6 November video. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-15610142.

Eliade, Mircea. 1987 [1957]. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Willard R. Trask (trans.). San Diego: Harcourt.

Foote, Kenneth E. 1997. Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Griffith, James S. 1992. Beliefs and Holy Places: A Spiritual Geography of the Pimería Alta. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Hobbs, Joseph J. 1995. Mount Sinai. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Huntsinger, Lynn, and María Fernández-Giménez. 2000. “Spiritual Pilgrims at Mount Shasta, California”. Geographical Review 90: 536-558.

Newport, Frank. 2012. God Is Alive and Well: The Future of Religion in America. New York: Gallup Press.

Raban, Jonathan. 1996. Bad Land: An American Romance. New York: Pantheon.

Rashtogi, Nina Shen. 2010. “Is Kosher Better for the Planet?” The Washington Post, 2 February. http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2010-02-02/opinions/36839736_1_kosher-meat-halal-meat-kosher-products.

Singh, Rana P. B. 1994. “Water Symbolism and Sacred Landscape in Hinduism.” Erdkunde 48: 210-227.

315

Warf, Barney and Morton Winsberg. 2010. “Geographies of Megachurches in the United States.” Journal of Cultural Geography 27(1): 33-51.

Worthen, Molly. 2012. “One Nation Under God?” The New York Times Sunday Review, 22 December. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/23/opinion/sunday/american-christianity-and-secularism-at-a-crossroads.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

Ten Recommended Books on the Geography of Religion

(For additional suggested readings, see the Contemporary Human Geography LaunchPad: http://www.macmillanhighered.com/launchpad/DomoshCHG1e.)

Esposito, John, Susan Tyler Hitchcock, Desmond Tutu, and Mpho Tutu. 2004. Geography of Religion: Where God Lives, Where Pilgrims Walk. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. In the tradition of National Geographic magazine, this comprehensive reference book is beautifully illustrated.

Falah, Ghazi-Walid, and Caroline Nagel (eds.). 2005. Geographies of Muslim Women: Gender, Religion, and Space. New York: Guilford Press. A collection of chapters by geographers that highlights the diversity of women’s experiences across the Islamic world.

Hart, John. 2006. Sacramental Commons: A Christian Ecological Ethics. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. The author suggests that local places and communities provide “sacraments,” or signs of divine presence, which give rise to an awareness of human interconnected-ness with all living things and our moral duty to care for the planet.

Murray, Stuart A. P. 2009. Hammond Atlas of World Religions: A Visual History of Our Great Faiths. Irvington, N.Y.: Hylas. Takes a historical look at the development of the world’s religions. This atlas contains beautifully rendered historical and topical maps, along with many photographs.

O’Brien, Joanne, and Martin Palmer. 2007. The Atlas of Religion: Mapping Contemporary Challenges and Beliefs. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Maps the nature, extent, and influence of the world’s major religions. Depicts how religions spread across space, their role in global issues such as hunger as well as conflict, and the locations of sacred places.

Orsi, Robert A. 2005. Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars who Study Them. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Examines twentieth-century American Catholicism and how people forge ties to heaven and Earth through their relationships to the Virgin Mary and the saints.

Stump, Roger W. 2008. The Geography of Religion: Faith, Place, and Space. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. An overview of a geographer’s approach to studying religion, encompassing their growth and spread, the diverse geographical scales that religion engages, and sacred spaces.

Timothy, Dallen J., and Daniel H. Olsen (eds.). 2006. Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys. London: Routledge. Acknowledging that faith is still the primary reason people travel, this collection of essays provides case studies of religious tourism and pilgrimage.

Tomalin, Emma. 2009. Biodivinity and Biodiversity: The Limits of Religious Environmentalism. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate. Argues that environmentalism may be a romantic Western notion which poorer nations cannot easily subscribe to. Case studies from India and Britain trace environmental concerns in divergent religious and material contexts.

Tweed, Thomas. 2008. Crossing and Dwelling: A Theory of Religion. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. This book’s premise is that religion is about movement, connection, and life as lived, rather than a static entity pinned to a certain place.