MOBILITY

6.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify the various ways that mobility and political geography interact.

Political events and developments can trigger massive human migrations, sometimes spanning continents. Moreover, the forces of globalization have accentuated the importance of mobility across political boundaries. However, political boundaries also act as barriers to the movement of people, ideas, knowledge, and resources.

MOVEMENT BETWEEN CORE AND PERIPHERY

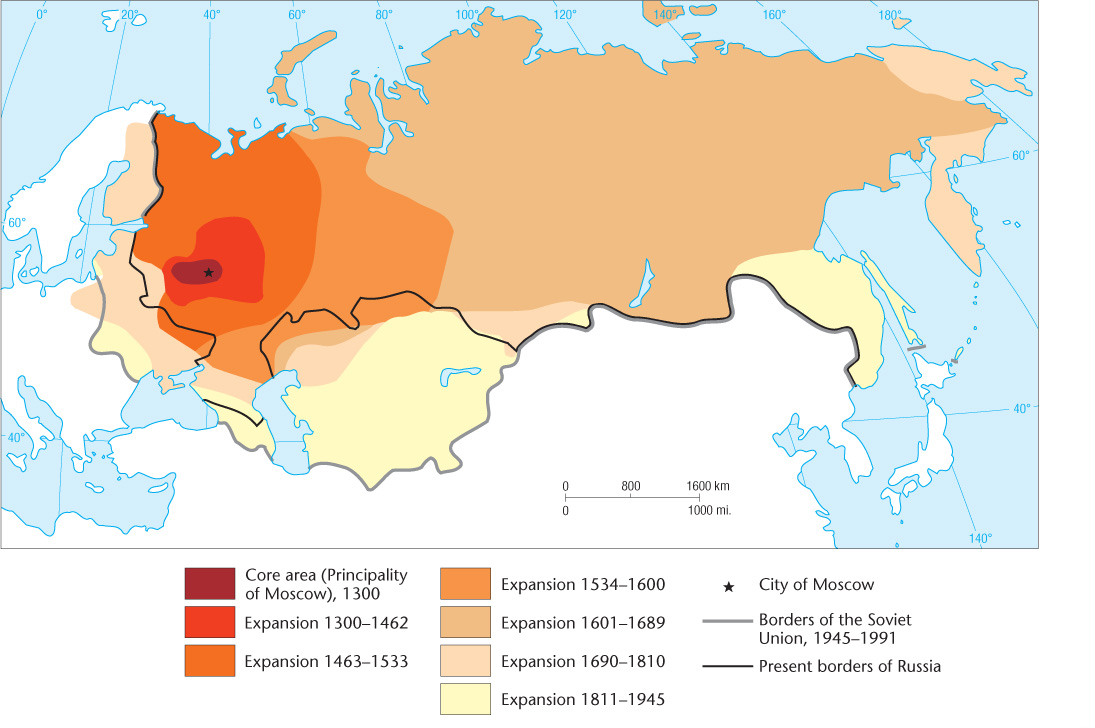

Many independent states sprang fully formed into the world, but some expanded outward when powerful political entities emerged from a small nucleus called a core area. These core political powers enlarged their territories by annexing adjacent lands, often over many centuries. Generally, core areas possess a particularly attractive set of resources for human life and culture. Larger numbers of people cluster there than in surrounding districts, especially if the area has some measure of natural defense against aggressive neighboring political entities. This denser population, in turn, may produce enough wealth to support a large army, which then provides the base for further expansion outward from the core area. Resources, people, and capital investment begin to flow between the core and peripheral territories, usually resulting in a further consolidation of the core’s wealth and power.

core area

The territorial nucleus from which a country grows in area and over time, often containing the national capital and the main center of commerce, culture, and industry.

In states formed in this way, the core area typically remains the country’s single most important district, housing the capital city and the cultural and economic heart of the nation. The core area is the node of a functional region. France expanded to its present size from a small core area around the capital city of Paris. China grew from a nucleus in the northeast, and Russia originated in the small principality of Moscow (Figure 6.14). The United States grew westward from a core between Massachusetts and Virginia on the Atlantic coastal plain, an area that still includes the national capital and the densest population in the country.

The evolution of independent countries in this manner produces the core-periphery configuration, described in Chapter 1 as typical of both functional and formal regions. Although the core dominates the periphery, a certain amount of friction exists between the two. Peripheral areas generally display pronounced, self-conscious regionality and occasionally provide the settings for secession movements. Even so, countries that diffused from core areas are, as a rule, more stable than those created all at once to fill a political void. The absence of a core area can blur or weaken citizens’ national identity and make it easier for various provinces to develop strong local or even foreign allegiances. Belgium and the Democratic Republic of the Congo offer examples of countries without political core areas. In the case of the Congo, this situation partly accounts for the history of secessionist conflicts and internecine wars since the country gained independence from colonial rule in 1960.

MOBILITY, DIFFUSION, AND POLITICAL INNOVATION

One of the consequences of colonialism was the creation of new patterns of mobility among the conquered populations. One pattern in particular contained the seeds of colonialism’s demise. Colonial rule in Africa depended on the establishment of a relatively small cadre of educated African civil servants. The colonial rulers selected those whom they considered the best and the brightest (and most politically cooperative) among their African subjects and sent them to the best universities in Europe. In addition to learning the skills required of colonial functionaries, they absorbed the ideals of Western political philosophy, such as the right of self-determination, independent self-rule, and individual rights. Educated Africans returned to their countries armed with these ideas and organized new nationalist movements to oppose colonial rule.

240

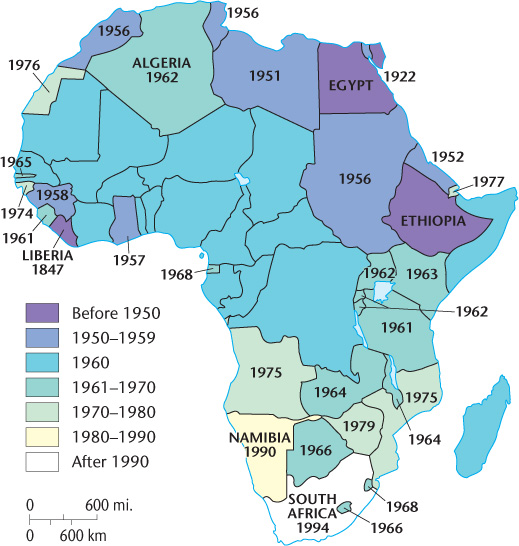

The consequences can be seen in the spread of political independence in Africa. In 1914 only two African countries—Liberia and Ethiopia—were fully independent of European colonial or white minority rule, and even Ethiopia later fell temporarily under Italian control. Influenced by developments in India and Pakistan, the Arabs of North Africa began a movement for independence. Their movement gained momentum in the 1950s and swept southward across most of the African continent between 1960 and 1965. Many of Africa’s great nationalist leaders of this period had obtained university degrees in England, Scotland, France, and other European countries. By 1994 African nationalists had helped spread the idea of independence into all remaining parts of the continent, eventually reaching the Republic of South Africa, formerly under white minority rule (Figure 6.15).

Despite its rapid spread, diffusion of African self-rule occasionally encountered barriers. Portugal, for example, clung tenaciously to its African colonies until 1975, when a change in government in Lisbon reversed a 500-year-old policy, allowing the colonies to become independent. In colonies containing large populations of European settlers, independence came slowly and usually with bloodshed. France, for example, sought to hold onto Algeria because many European colonists had settled there. The country nonetheless achieved independence in 1962, but only after years of violence. In Zimbabwe, a large population of European settlers refused London’s orders to move toward majority rule, resulting in a bloody civil war and delaying the country’s independence until 1979.

241

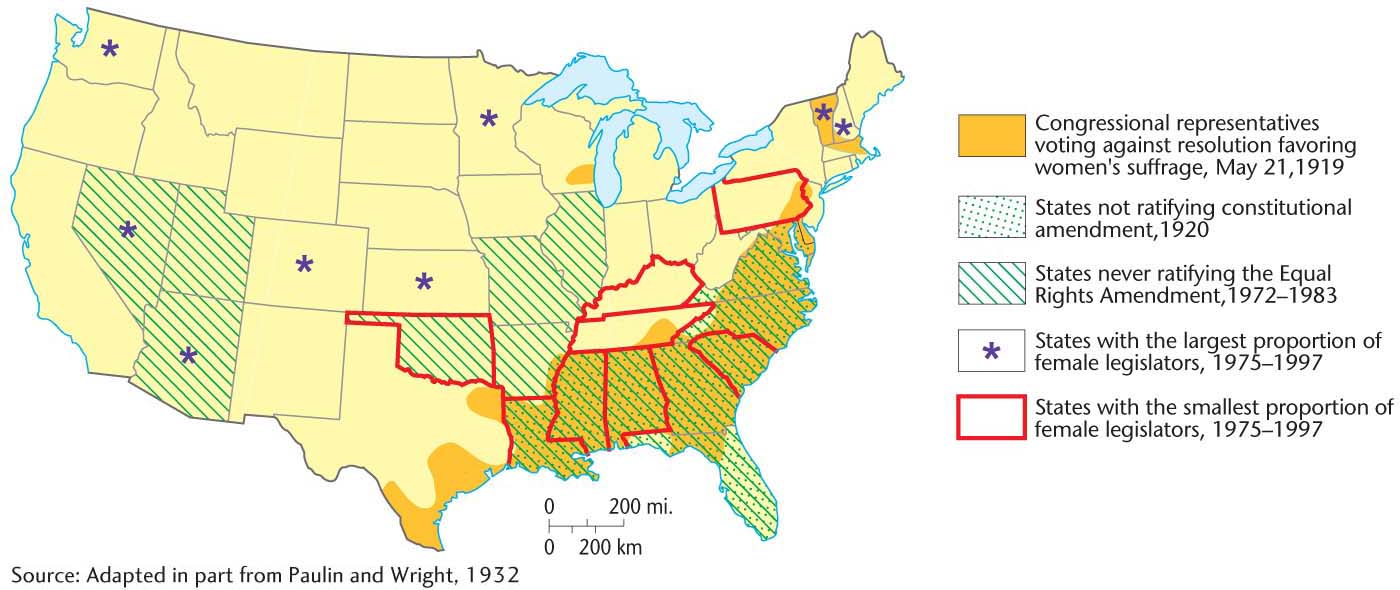

On a quite different scale, political innovations also spread within independent countries. American politics abounds with examples of cultural diffusion. A classic case is the spread of suffrage for women, a movement that culminated in 1920 with the ratification of a constitutional amendment (Figure 6.16). Opposition to women’s suffrage was strongest in the U.S. South, a region that later exhibited the greatest resistance to ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment and displayed the most reluctance to elect women to public office.

Federal statutes permit, to some degree, laws to be adopted in the individual functional subdivisions. In the United States and Canada, for example, each state and province enjoys broad lawmaking powers, vested in the legislative bodies of these subdivisions. The result is often a patchwork legal pattern that reveals the processes of cultural diffusion at work. A good example is the clean air movement, which began in California with the initiation of state legislation regulating automotive and industrial emissions. It later spread to other states and provided the model for clean air legislation at the federal level.

242

THE FORCED MOBILITY OF VIOLENT CONFLICT

Since there have been states, there have been refugees. We learned in Chapter 3 that a refugee is a type of forced migrant, a definition that we expand upon here by looking to the United Nations. The UN definition of refugee pivots around people’s relationship to the state. According to the extended definition in the UN 1951 Refugee Convention, “Refugees have to move if they are to save their lives or preserve their freedom. They have no protection from their own state—indeed it is often their own government that is threatening to persecute them.” Often repression is driven by cultural difference—based on religion, race, or ethnicity—as much as by political disagreement. It seems that the very idea of the state contains both the promise of stability and protection and the threat of displacement and persecution. As geographers Jennifer Hyndman and Wenona Giles observe, “Displacement is the underbelly of mobility, a kind of movement that expresses the violent political relation of people to place.”

Most refugees are fleeing some form of armed conflict including interstate wars, civil wars, insurgencies, and counterinsurgencies. Syria presents a tragic but all-too-common example of a twenty-first-century refugee crisis. Its citizenry is a complex assortment of religious and ethnic identities, including Arab-Sunni Muslim, Arab-Alawite (a Muslim Shi’ite sect), Kurd-Sunni, and Greek Orthodox Christian. The Baath Party controlled the government for decades, led by President Bashir al-Assad, an Alawite. When the Arab Spring swept through surrounding countries, overthrowing entrenched regimes, peaceful street protests broke out in Syria demanding a change in government. After violent government reprisals, they soon developed into armed rebellion with multiple militias and ethnic, political, and religious factions from Syria and nearby countries taking sides in the fight. The protests subsequently escalated into a full-blown civil war. By 2013 Syria was the source of at least 1.6 million refugees who flowed into the nearby countries of Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan at a rate of 250,000 per month. Jordan hosted the largest numbers of refugees, with its al-Zaatari refugee camp vying for the dubious distinction as the world’s largest.

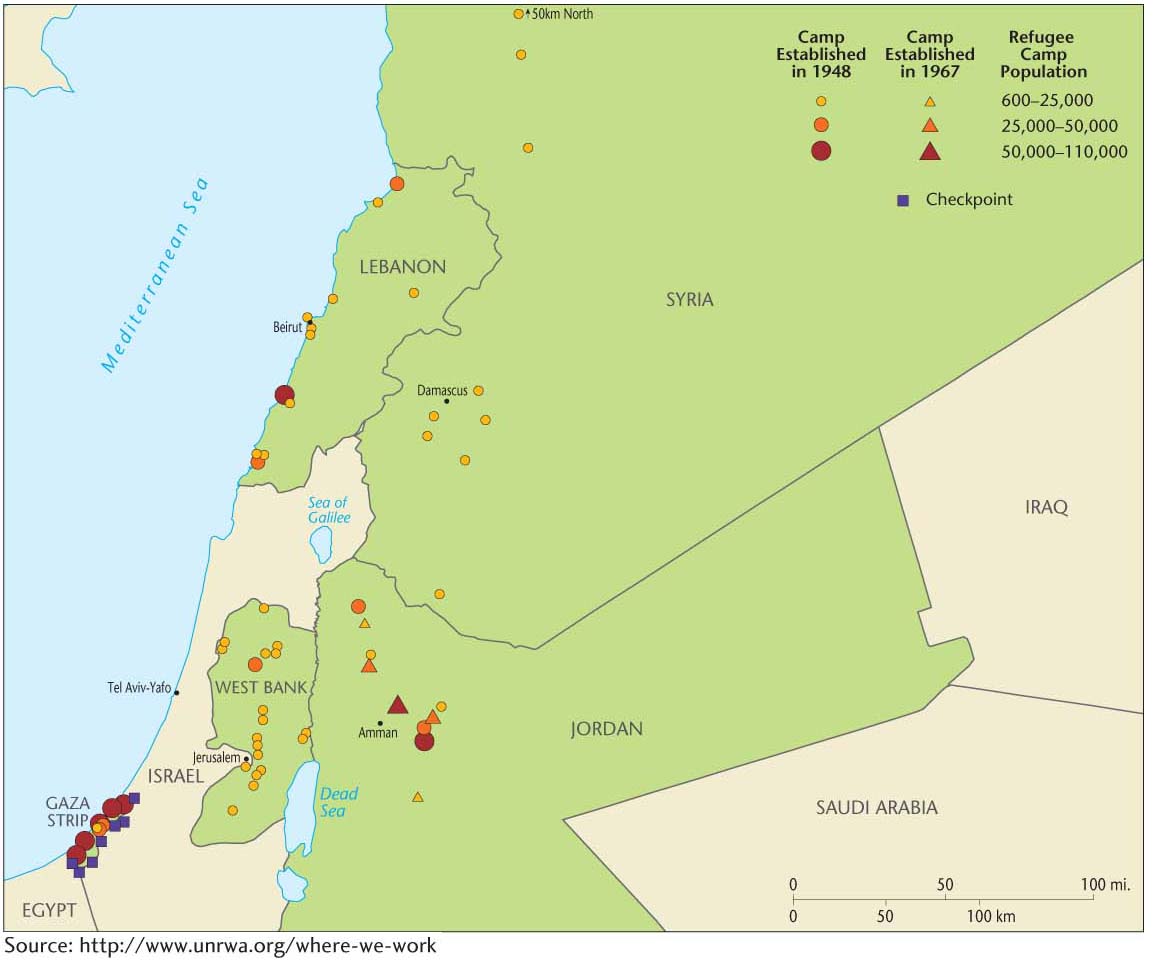

Worldwide, the number of refugees has been growing in the twenty-first century. Estimates vary greatly for political reasons (governments often impede accurate counting) as well as practical considerations (people on the move across borders are difficult to count). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is widely recognized as the most reliable source. As of 2012, the UN estimated that there were 15.2 million refugees worldwide, plus another 4.8 million semipermanent Palestinian refugees resulting from the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 and the 1967 Arab-Israeli war (Figure 6.17). The great majority of refugees may be found in developing countries, many of which do not have the adequate infrastructure and resources to manage the flow of forced migrants. This is where the UNHCR comes in. Its primary mission is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. In practical terms, this means delivering shelters, clothing, and medical and personal hygiene supplies to millions of people in hundreds of refugee camps. Refugee camps are meant to be temporary settlements to house and care for displaced persons until they can be safely repatriated. Sometimes repatriation takes years, in which case the UNHCR acts as a surrogate state, securing birth certificates, facilitating schooling, and improving sanitary infrastructure.

REFUGEE SPACES

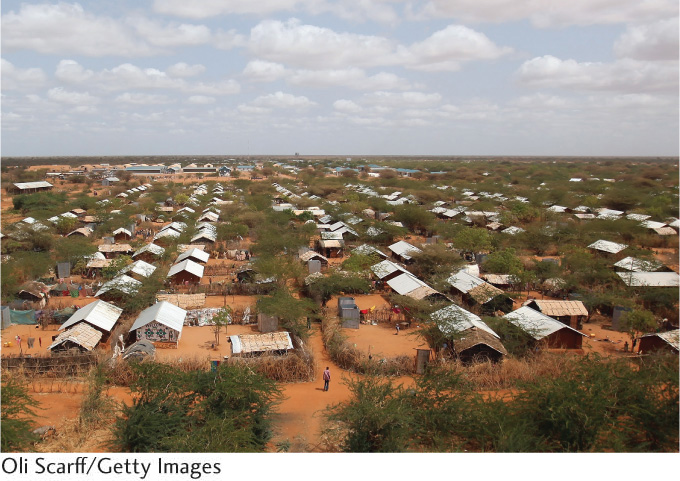

There is thus a nearly hidden political geography of displaced persons worldwide. The UNHCR operates hundreds of camps and settlements housing millions of people in 124 countries. Although meant as temporary solutions, some camps last decades and become major population centers absent on most maps. Dadaab, Kenya, is the location of one of the oldest, established in l991 and currently housing at least 320,000 people, probably many more (Figure 6.18). The camp and its population do not show up on standard world atlases. Imagine an atlas without St. Louis, Missouri, or Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. cities with equivalent population totals. Millions of people are born and come into adulthood in refugee camps with no promise of becoming citizens in a new country and little hope of returning to a home they never knew. The UN refers to such cases as a protracted refugee situation (PRS). An increasing number of refugee camps fall under this designation, thus creating a geography of semipermanent settlements the size of major cities that remain invisible on the world map.

protracted refugee situation

Results when people are born and mature into adulthood in refugee camps with no promise of becoming citizens in a new country and little hope of returning to their home country.

243

244

Geographers have taken an interest in PRSs, which present conditions of both mobility and long-term stasis. From a feminist political geography perspective, northern, developed states perceive refugees very differently if they are in a PRS or are actively on the move. Jennifer Hyndman and Wenona Giles show that refugees in PRSs are feminized based on their location and legal status. That is, refugees in PRSs are viewed as externalized, motionless, and politically passive and powerless, and thus are coded as nonthreatening/feminine. In contrast, refugees seeking asylum in northern, developed countries are viewed as internalized, on the move, and politically active and vocal, and thus are coded as threatening to both national security and the welfare state. Such feminization, Hyndman and Giles argue, can serve to reinforce the conditions that create PRSs by reducing urgency and lowering priorities for official action.

In another PRS study, geographer Adam Ramadan reveals the relative and contingent qualities of mobility/stasis. Ramadan categorizes the refugee camp as a distinctive political space. PRS camps can become, in his words, “spaces of exceptional sovereignty.” To illustrate his point, he examines the case of Palestinian refugee camps within Lebanon during the brief 2006 war between the Israel and Hizbullah, a Shi’ite political and paramilitary organization. When Israel bombed Hizbullah positions in southern Lebanon, nearly 5,000 Lebanese citizens fled to the Palestinian refugee camps of El-Bus and Rashidieh for shelter and protection. Over generations, Palestinian refugees in southern Lebanon have evolved a great degree of internal autonomy over camp political and social affairs, thus gaining a degree of sovereignty over these spaces. They exercised that sovereignty, making the decision to receive thousands of the displaced Lebanese citizens into their private homes and public buildings and care for their well-being. The study shows how the 2006 war inverted the normal relationship of host (Lebanon) and guest (Palestinian refugee). In addition, the war shifted Lebanese citizens’ vision of the camps from dangerous, no-go zones to spaces of shelter and refuge. Finally, it demonstrated and reinforced Palestinian refugees’ sovereignty over spaces originally conceived to be temporary and void of political status.

THE DIFFUSION OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE

Mass news media and political leaders often speak of the civil wars and internal armed conflicts that produce masses of refugees worldwide as chaotic and spotty in time and space. Unlike traditional interstate warfare with readily identifiable borders, civil wars are often diffuse with no discernable front. According to geographers Sebastian Schuttea and Nils B. Weidmann, that does not mean there are no regular spatial patterns to be found. In fact, they suggest, civil wars and conflicts exhibit common diffusion characteristics.

Many observers have recognized the relevance of contagion diffusion in the spread of armed conflict from one state to another. Schuttea and Weidman’s study showed, however, that diffusion patterns are also relevant to analyzing the spread of a single conflict within state boundaries. Using data from four recent internal armed conflicts in Europe and Africa, they analyzed how violence spread in time and space. They found that in all cases violence spread in a pattern of expansion diffusion. They propose that such cases illustrate what they call escalation diffusion in civil wars and armed conflicts. By this, they mean that civil wars “intensify” or “escalate” through diffusion of violence across ever-greater areas over time. They also note that in one case in their study, relocation diffusion—the movement of violence to another location— took place as well, although expansion diffusion was the main pattern of spreading of violence. Such modeling of political violence may aid in predicting, and thus possibly preventing, the escalation of civil wars.

contagious diffusion

A type of expansion diffusion in which cultural innovation spreads by person-to-person contact, moving wavelike through an area and population without regard to social status.

245

expansion diffusion

The spread of innovations within an area in a snowballing process, so that the total number of knowers or users becomes greater and the area of occurrence grows.

escalation diffusion

The idea that civil wars may escalate through the diffusion of violence across ever-greater areas over time.

relocation diffusion

The spread of an innovation or other element of culture that occurs with the bodily relocation (migration) of the individual or group responsible for the innovation.