MOBILITY

7.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Discuss how and why the world’s religions became distributed as they are today.

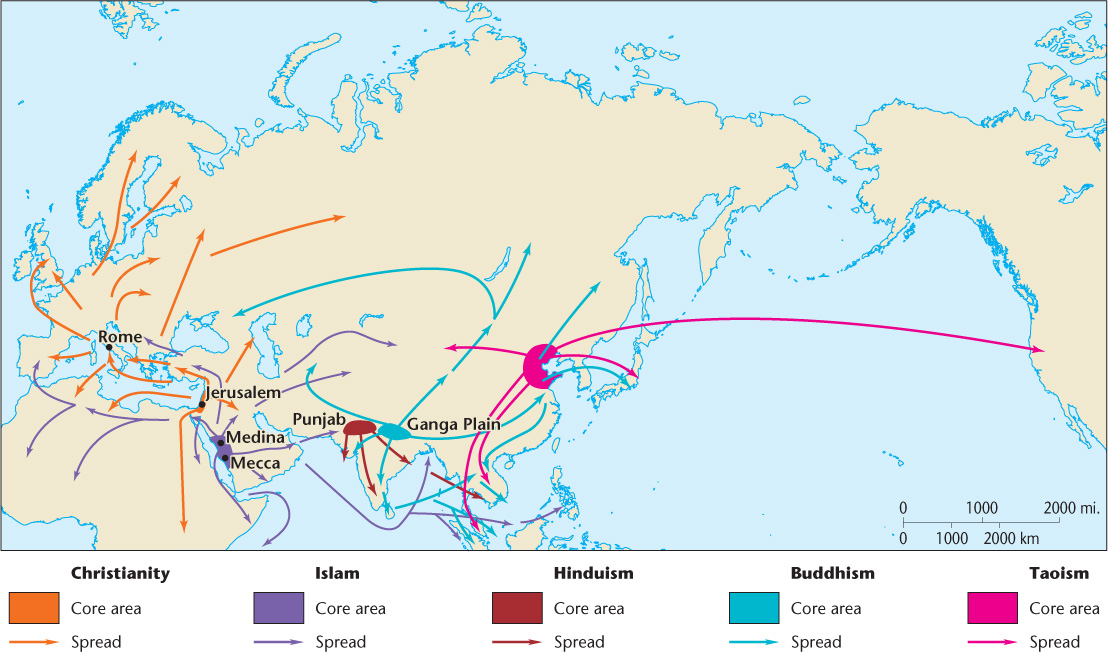

Religions, according to religious studies scholar Thomas Tweed, can be thought of as “flows that intensify joy and confront suffering by drawing on human and suprahuman forces to make homes and cross boundaries.” In other words, religions have always been on the move, crossing oceans and borders to establish new dwelling places. To a remarkable degree, the origin of the major religions was concentrated spatially in three principal culture hearth areas (Figure 7.14). A culture hearth is a focused geographic area where important innovations are born and from which they spread. Many religions mandate periodic return of the faithful to these culture hearths in order to confirm or renew their faith.

culture hearth

A focused geographic area where important innovations are born and from which they spread.

THE SEMITIC RELIGIOUS HEARTH

All three of the great monotheistic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—arose among Semitic peoples who lived in or on the margins of the deserts of southwestern Asia, in the Middle East (see Figure 7.14). Judaism, the oldest of the three, originated some 4000 years ago. Only gradually did its followers acquire dominion over the lands between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River—the territorial core of modern Israel. Christianity, whose parent religion is Judaism, originated here about 2000 years ago. Seven centuries later, the Semitic culture hearth once again gave birth to a major faith when Islam arose in western Arabia, partly from Jewish and Christian roots.

Religions spread by both relocation and expansion diffusion. Recall from Figure 1.8 that expansion diffusion can be divided into hierarchical and contagious subtypes. In hierarchical diffusion, ideas become implanted at the top of a society, leapfrogging across the map to take root in cities and bypassing smaller villages and rural areas. Because their main objective is to convert nonbelievers, proselytic faiths are more likely to diffuse than ethnic religions, and it is not surprising that the spread of monotheism was accomplished largely by Christianity and Islam, rather than Judaism. From Semitic southwestern Asia, both of the proselytic monotheistic faiths diffused widely, as shown in Figure 7.14.

Christians, observing the admonition of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew—“Go ye therefore and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you”—initially spread through the Roman Empire, using the splendid system of imperial roads to extend the faith. In its early centuries of expansion, Christianity displayed a spatial distribution that clearly reflected hierarchical diffusion. The early congregations were established in cities and towns, temporarily producing a pattern of Christianized urban centers and pagan rural areas. Indeed, traces of this process remain in our language. The Latin word pagus, “countryside,” is the root of both pagan and peasant, suggesting the ancient connection between non-Christians and the countryside.

The scattered urban clusters of early Christianity were created by such missionaries as the apostle Paul, one of Jesus’s disciples who moved from town to town bearing the news of the emerging faith. In later centuries, Christian missionaries often used the strategy of converting kings or tribal leaders, setting in motion additional hierarchical diffusion. The Russians and Poles were converted in this manner. Some Christian expansion was militaristic, as in the reconquest of Iberia from the Muslims and the invasion of Latin America. Once implanted in this manner, Christianity spread farther by means of contagious diffusion. When applied to religion, this method of spread is called contact conversion and is the result of everyday associations between believers and nonbelievers.

contact conversion

The spread of religious beliefs by personal contact.

287

The Islamic faith spread from its Semitic hearth area in a predominately militaristic manner. Obeying the command in the Qur’an that they “do battle against them until there be no more seduction from thetruth and the only worship be that of Allah,” the Arabs expanded westward across North Africa in a wave of religious conquest. The Turks, once converted by the Arabs, carried out similar Islamic conquests. In a different sort of diffusion, Muslim missionaries followed trade routes eastward to implant Islam hierarchically in the Philippines, Indonesia, and the interior of China. Tropical Africa is the current major region of Islamic expansion, an effort that has produced competition with Christians for the conversion of animists. As a result of missionary successes in sub-Saharan Africa and high birthrates in its older sphere of dominance, Islam has become the world’s fastest-growing religion in terms of the number of new adherents.

THE INDUS-GANGES RELIGIOUS HEARTH

The second great religious hearth area lay in the plains fringing the northern edge of the Indian subcontinent. This lowland, drained by the Ganges and Indus rivers, gave birth to Hinduism and Buddhism. Hinduism, which is at least 4000 years old, was the earliest faith to arise in this hearth. Its origin apparently took place in Punjab, from where it diffused to dominate the subcontinent, although some historians believe that the earliest form of Hinduism was introduced from Iran by emigrating Indo-European tribes about 1500 B.C.E. Missionaries later carried the faith, in its proselytic phase, to overseas areas, but most of these converted regions were subsequently lost to other religions.

288

Branching off from Hinduism, Buddhism began in the foothills bordering the Ganges Plain about 500 B.C.E. (see Figure 7.14). For several centuries, it remained confined to the Indian subcontinent, but missionaries later carried the religion to China (100 B.C.E. to 200 C.E.), Korea and Japan (300 to 500 C.E.), Southeast Asia (400 to 600 C.E.), Tibet (700 C.E.), and Mongolia (1500 C.E.). Buddhism developed many regional forms throughout Asia, except in India, where it was ultimately accommodated within Hinduism.

The diffusion of Buddhism, like that of Christianity and Islam, continues to the present day. Some 2 million Buddhists live in the United States, about the same number as Episcopalians. Mostly, their presence is the result of relocation diffusion by Asian immigrants to the United States, where immigrant Buddhists outnumber Buddhist converts by 3 to 1.

THE EAST ASIAN RELIGIOUS HEARTH

K’ung Fu-tzu and Lao Tzu, the respective founders of Confucianism and Taoism, were contemporaries who reputedly once met with each other. Both religions were adopted widely throughout China only when the ruling elite promoted them. In the case of Confucianism, this was several centuries after the master’s death. During his life, Kong Fu-tzu wandered about with a small band of disciples trying to convince rulers to put his ideas on good governance into practice. But he was shunned even by lowly peasants, who criticized him as “a man who knows he cannot succeed but keeps trying.” Thus, early attempts at contagious diffusion were unsuccessful, whereas hierarchical diffusion from politicians and schools eventually spread Confucianism from the top down. Taoism, as well, did not gain wide acceptance until it was promoted by the ruling Chinese elite.

After 1949, China’s communist government officially repressed organized religious expression, dismissing it as a relic of the past. In other words, the government attempted to erect an absorbing barrier that would not only halt the spread of religion but would also erase it from Chinese public and private life. As noted in Chapter 1, absorbing barriers are rarely completely successful, and this example is no exception. Although temples were converted to secular uses, and even looted and burned, religion was driven underground rather than eradicated. After the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), which aimed to purify Chinese society of bourgeois excesses such as religion, tolerance for religious expression grew. However, the Chinese Communist Party’s official stance still holds that religious and party affiliations are incompatible; thus, some party officials are reluctant to divulge their religious status. This, combined with the fact that many Chinese practice elements of several Taoic faiths simultaneously, makes the precise enumeration of adherents difficult.

289

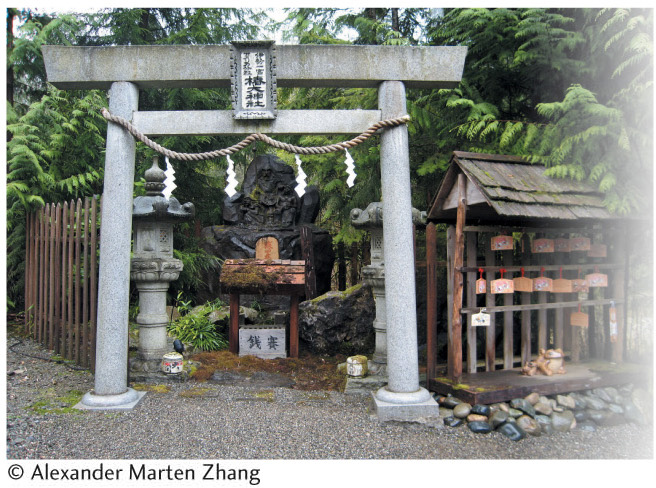

Taoism and Confucianism have spread with the Chinese people through trade and military conquest. Thus, people in Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, along with mainland China, practice these beliefs or at least have been influenced by them. Today, Chinese and Japanese migrants alike have relocated their belief systems across the globe, as the image of the Tsubaki Shinto Shrine in Washington State shown in Figure 7.15 confirms.

RELIGIOUS PILGRIMAGE

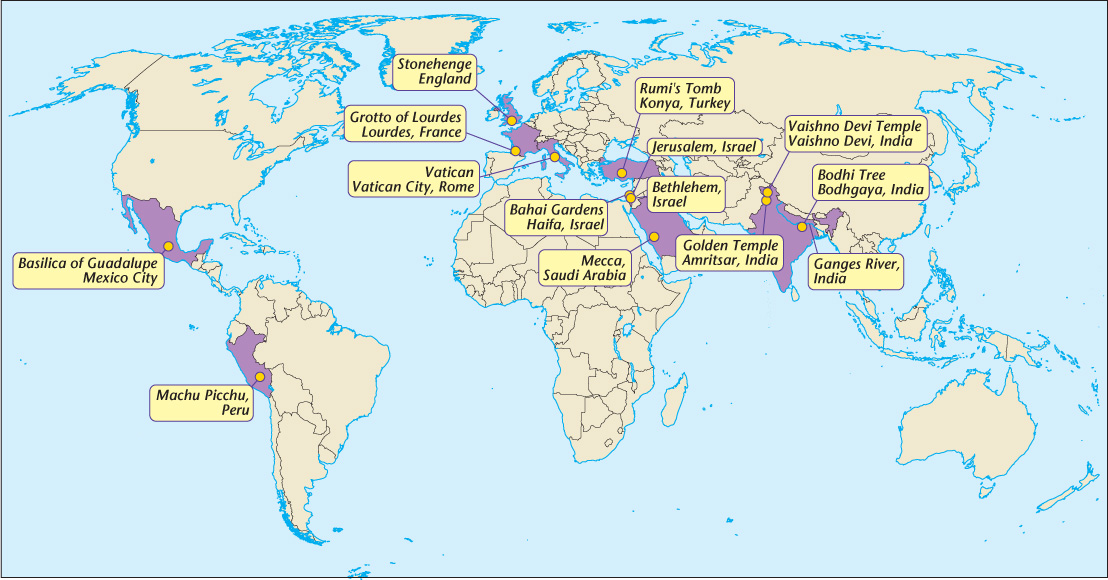

For many religious groups, journeys to sacred places, or pilgrimages, are an important aspect of faith-based mobility (Figure 7.16). Pilgrimages are typical of both ethnic and proselytic religions. They are particularly significant for followers of Islam, Hinduism, Shintoism, and Roman Catholicism. Along with missionaries, pilgrims constitute one of the largest groups of people voluntarily on the move for religious reasons: religious pilgrimage is the number one driver of tourism. Pilgrims do not aim to convert people to their faith through their journeys. Rather, they enact in their travels a connection with the sacred spaces of their faith. Indeed, some religions mandate pilgrimage, as is the case with Islam, where pilgrimage to Mecca is one of the Five Pillars of the faith.

pilgrimages

Journeys to places of religious importance.

290

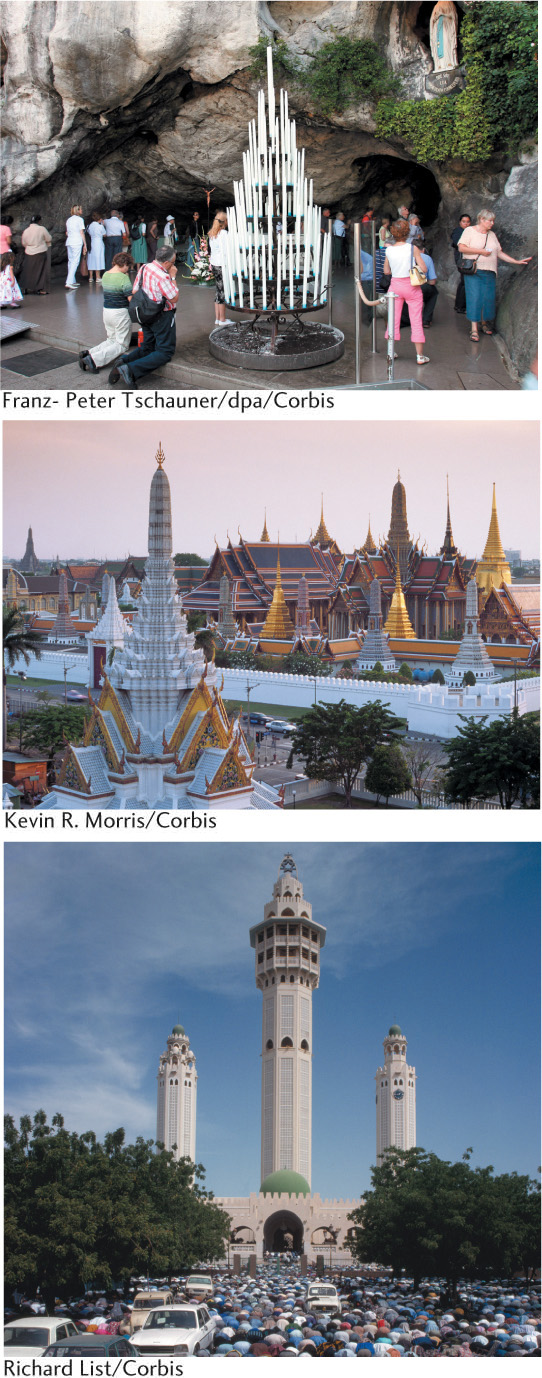

The sacred places visited by pilgrims vary in character (Figure 7.17). Some have been the setting for miracles; a few are the regions where religions originated or areas where the founders of the faith lived and worked; others contain sacred physical features such as rivers, caves, springs, and mountain peaks; and still others are believed to house gods or are religious administrative centers where leaders of the religion reside. Examples include the Arabian cities of Mecca and Medina in Islam, which are cities where Muhammed resided and thus form Islam’s culture hearth; Rome, the home of the Roman Catholic pope; the French town of Lourdes, where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to a girl in 1858; the Indian city of temples on the holy Ganges River, Varanasi, a destination for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain pilgrims; and Ise, a shrine complex located in the culture hearth of Shintoism in Japan. Places of pilgrimage might be regarded as places of spatial convergence, or nodes, of functional culture regions.

Religion provides the stimulus for pilgrimage by offering those who participate in the purification of their souls or the attainment of some desired objective in their lives, by mandating pilgrimage as part of devotion, or by allowing the faithful to connect with important historic sites of their faith. For this reason, pilgrims often journey great distances to visit major shrines. Other sites of lesser significance draw pilgrims only from local districts or provinces. Pilgrimages can have tremendous economic impact because the influx of pilgrims is a form of tourism.

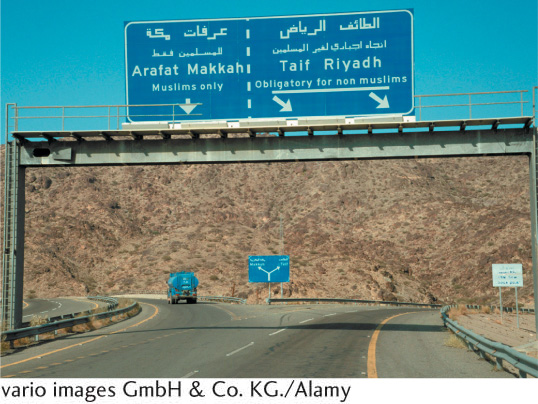

In some localities, the pilgrim trade provides the only significant source of revenue for the community. Lourdes, a town of about 16,000, attracts between 4 million and 5 million pilgrims each year, with many seeking miraculous cures at the famous grotto where the Virgin Mary reportedly appeared. Not surprisingly, among French cities, Lourdes ranks second only to Paris in its number of hotels, although most of these are small. Mecca, a small city, annually attracts millions of Muslim pilgrims from every corner of the Islamic culture region as they perform the hajj, or Fifth Pillar of Islam, which all able-bodied Muslims who can afford the journey are encouraged to perform at least once in their lifetime. By land, by sea, and (mainly) by air, the faithful come to this hearth of Islam, a city closed to all non-Muslims (Figure 7.18). Such mass pilgrimages obviously have a major impact on the development of transportation routes and carriers, as well as other provisions such as inns, food, water, and sanitation facilities.

291