CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

7.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe how religions have left their particular mark on the cultural landscape.

Religion is a vital aspect of culture; its visible presence can be quite striking, reflecting the role played by religious motives in the human transformation of the landscape. In some places, the religious aspect is the dominant visible evidence of culture, producing sacred landscapes. At the opposite extreme are areas almost purely secular in appearance. Religions differ greatly in visibility, but even those least apparent to the eye usually leave some subtle mark on the countryside.

RELIGIOUS STRUCTURES

The most obvious religious contributions to the landscape are the buildings erected to house divinities or to shelter worshippers. These structures vary greatly in size, function, architectural style, construction material, and degree of ornateness (Figure 7.30). To Roman Catholics, for example, the church building is literally the house of God, and the altar is the focus of key rituals. Partly for these reasons, Catholic churches are typically large, elaborately decorated, and visually imposing. In many towns and villages, the Catholic house of worship is the focal point of the settlement, exceeding all other structures in size and grandeur. In medieval European towns, Christian cathedrals were the tallest buildings, representing the supremacy of religion over all other aspects of life.

301

For many Protestants—particularly the traditional Calvinistic chapel-goers of British background, including Presbyterians and Baptists—the church building is, by contrast, simply a place to assemble for worship. The result is a small, simple structure that appeals less to the senses and more to personal faith. For this reason, traditional Protestant houses of worship typically are not designed for comfort, beauty, or high visibility but instead appear deliberately humble (see Figure 7.30, middle). Similarly, the religious landscape of the Amish and Mennonites in rural North America, the “plain folk,” is very subdued because they reject ostentation in any form. Some of their adherents meet in houses or barns, and the churches that do exist are very modest in appearance, much like those of the southern Calvinists.

So-called megachurches present a recent twist on the Protestant house of worship, one that shuns humbleness and plainness for size and grandeur (Figure 7.31). Located in suburban areas, but also on the rise in Protestant areas worldwide, megachurches count from 2000 to 10,000 members and rely on a business-oriented approach to designing spaces and services in line with their congregation’s wishes. These include plenty of parking and bathrooms, but also recreational facilities, high-tech audio visual sermon delivery, and casual dress codes. Megachurches also foster a sense of connectedness and community in an increasingly secular world. Geographers Barney Warf and Morton Winsberg (2010), who have studied megachurches, claim that they are “the new face of American religion, a threat that many traditional denominations have understandably viewed with alarm.”

megachurch

Large Protestant church structures, usually located in suburban areas of the United States, which have large congregations (2000-10,000 members) and utilize business models to tailor their spaces and services to their congregation’s needs.

302

Islamic mosques are usually the most imposing structures in the landscape, whereas the visibility of Jewish synagogues varies greatly. Hinduism has produced large numbers of visually striking temples for its multiplicity of gods, but much worship is practiced in private households with their own personal shrines (Figure 7.32).

Nature religions such as animism generally place only a subtle mark on the landscape. Nature itself is sacred, and imposing features already present in the landscape—mountains, waterfalls, and grottos, for example—mean that few human-made shrines are needed.

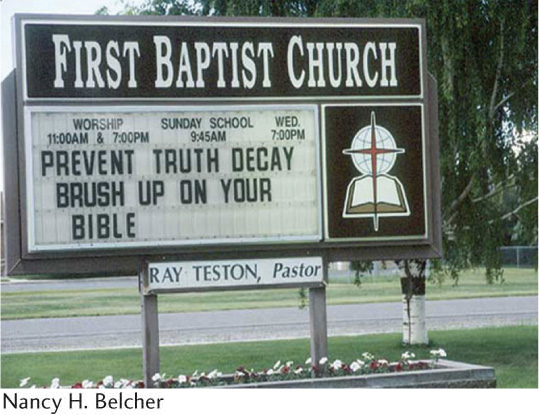

Paralleling this contrast in church styles are attitudes toward roadside shrines and similar manifestations of faith. Catholic culture regions typically abound with shrines, crucifixes, and other visual reminders of religion, as do some Eastern Orthodox Christian areas. Protestant areas, by contrast, are bare of such symbolism. Their landscapes instead display such features as signboards advising the traveler to “get right with God,” a common sight in the southern United States (Figure 7.33).

FAITHFUL DETAILS

Not only buildings but also other architectural choices, such as color and landscaping elements, can convey spiritual meaning through the landscape. Consider the color green. The image of a Muslim mosque in northern Nigeria in Figure 7.34 depicts how green—sacred in Islam—appears often on mosque domes and minarets, the tall circular towers from which Muslims are called to prayer. The prophet Muhammad declared his favorite color to be green, and his cloak and turban were said to be green. In Christianity, green also has positive connotations, symbolizing fertility, freedom, hope, and renewal. It is used in decorations, such as banners, and for clergy vestments, especially those associated with the Trinity and with the Epiphany season.

303

Water, often used as a decorative element in fountains, baths, and pools, has religious meaning. In fact, all three of the great desert monotheisms— Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—consider water to have a special status in religious rituals. In general, followers of all three religions believe water has the ability to purify and cleanse the body as well as to purify and cleanse the soul of sins. Muslims use water in ablutions, or washing, of the hands, face, or ears before daily prayers and other rituals. Footbaths, or ablution fountains, are important features located outside of mosques, and decorating with water, particularly pools and fountains, is a common practice in Islamic architecture. Central to Christianity is baptism, where the newborn infant or adult convert is sprinkled with or fully immersed in holy water, symbolizing the cleansing of original sin for infants and repentance or cleansing from sin for adults. Jews may engage in a ritual bath, known as a mikveh, before important events, such as weddings (for women), or on Fridays, the evening of the Jewish Sabbath (for men). The story of the Great Flood, found in the Book of Genesis (common to both Jews and Christians), depicts the washing away of the sins of the world so that it could be born anew.

LANDSCAPES OF THE DEAD

Religions differ greatly in the type of tribute each awards to its dead. These variations appear in the cultural landscape. The few remaining Zoroastrians, called Parsees, who preserve a once-widespread Middle Eastern faith now confined to parts of India, have traditionally left their dead exposed to be devoured by vultures. Thus, the Parsee dead leave no permanent mark on the landscape. Hindus cremate their dead. Having no cemeteries, their dead, as with the Parsees, leave no obvious mark on the land. Yet on the island of Bali in Indonesia, Hinduism has blended with animism such that temples to family ancestors occupy prominent places outside the houses of the Balinese, a landscape feature that does not exist in India itself (see Figure 7.32).

304

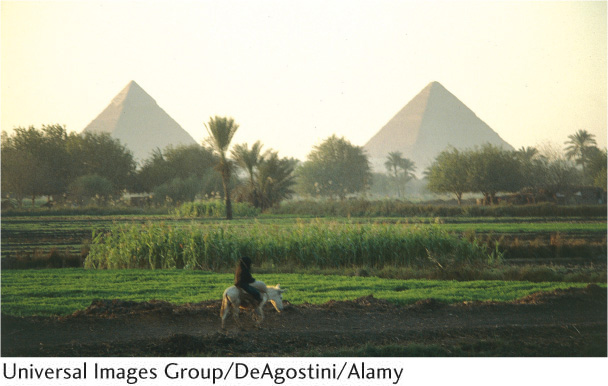

In Egypt, spectacular pyramids and other tombs were built to house dead leaders. These monuments, as well as the modern graves and tombs of the rural Islamic folk of Egypt, lie on desert land not suitable for farming (Figure 7.35). Muslim cemeteries are usually modest in appearance, but spectacular tombs are sometimes erected for aristocratic persons, giving us such sacred structures as the Taj Mahal in India (Figure 7.36), one of the architectural wonders of the world.

Taoic Chinese typically bury their dead, setting aside land for that purpose and erecting monuments to their deceased kin. In parts of China—reflecting its pre-communist history—cemeteries and ancestral shrines take up as much as 10 percent of the land in some districts, greatly reducing the acreage available for agriculture.

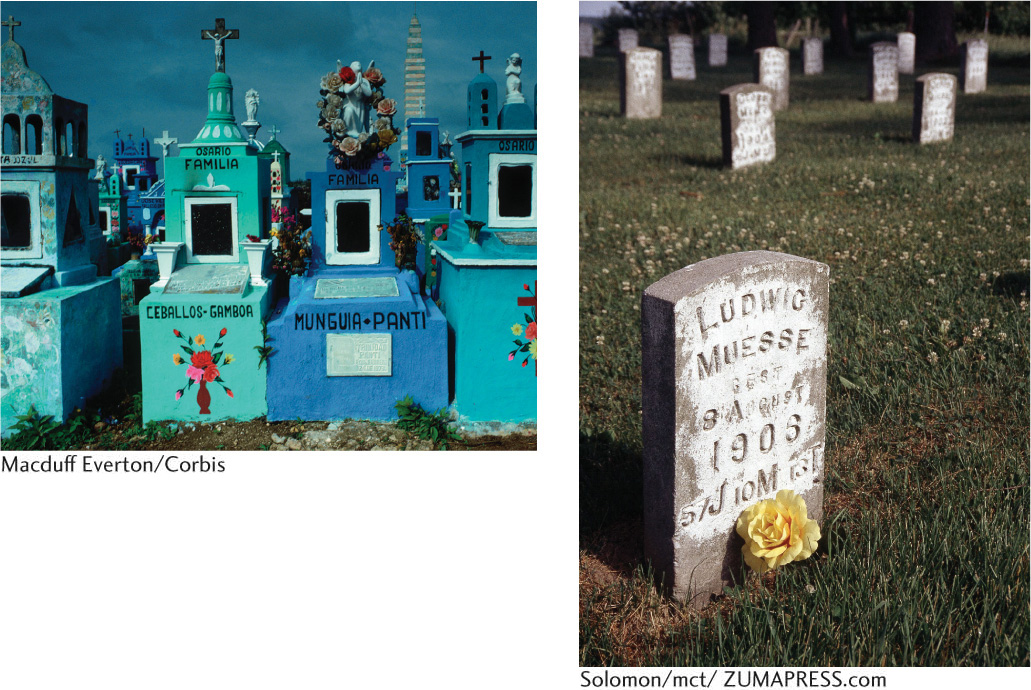

Christians also typically bury their dead in sacred places set aside for that purpose. These sacred places vary significantly from one Christian denomination to another. Some graveyards, particularly those of Mennonites and southern Protestants, are very modest in appearance, reflecting the reluctance of these groups to use any symbolism that might be construed as idolatrous. Among certain other Christian groups, such as Roman Catholics and members of the various Orthodox Churches, cemeteries are places of color and elaborate decoration (Figure 7.37).

Cemeteries often preserve truly ancient cultural traits because people as a rule are reluctant to change their practices relating to the dead. The traditional rural cemetery of the southern United States provides a case in point. Freshwater mussel shells are placed atop many of the elongated grave mounds, and rose bushes and cedars are planted throughout the cemetery. Recent research suggests that the use of roses may derive from the worship of an ancient, pre-Christian mother goddess of the Mediterranean lands. The rose was a symbol of this great goddess, who could restore life to the dead. Similarly, the cedar evergreen is an age-old pagan symbol of death and eternal life, and the use of shell decoration derives from an animistic custom in West Africa, the geographic origin of slaves in the American South. Although the present Christian population of the South is unaware of the origins of their cemetery symbolism, it seems likely that their landscape of the dead contains animistic elements thousands of years old, revealing truly ancient beliefs and cultural diffusions.

305

SACRED SPACE

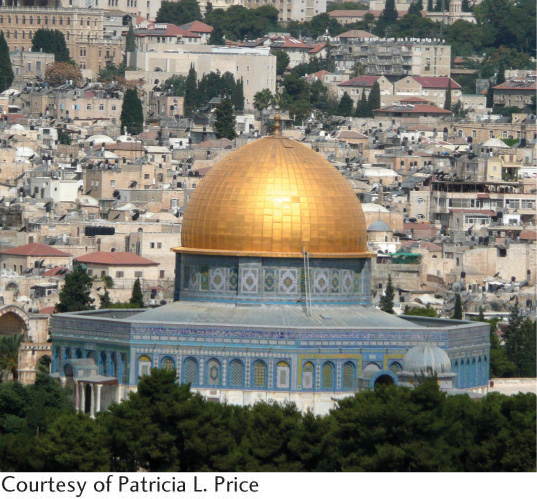

Sacred spaces consist of natural and/or human-made sites that possess special religious meaning that is recognized as worthy of devotion, loyalty, fear, or esteem. By virtue of their sacredness, these special places might be avoided by the faithful, sought out by pilgrims, or barred to members of other religions (see Figure 7.18). Often, sacred space includes the site of supposed supernatural events or is viewed as the abode of gods. Cemeteries, too, are also generally regarded as a type of sacred space. So is Mount Sinai, described by geographer Joseph Hobbs as endowed “with special grace,” where God instructed the Hebrews to “mark out the limits of the mountain and declare it sacred.” Conflict can result if two religions venerate the same space. In Jerusalem, for example, the Muslim Dome of the Rock, on the site where Muhammad is believed to have ascended to heaven, stands above the Western Wall, the remnant of the ancient Jewish temple (Figure 7.38; see Patricia’s Notebook and the World Heritage Site). These two religions literally claim the same space as their holy site, which has led to conflict.

sacred spaces

Areas recognized by a religious group as worthy of devotion, loyalty, esteem, or fear to the extent that they become sought out, avoided, inaccessible to nonbelievers, or removed from economic use.

Sacred space is receiving increased attention in the world. In the mid-1990s, the internationally funded Sacred Land Project began to identify and protect such sites, 5000 of which have been cataloged in the United Kingdom alone. Included are such places as ancient stone circles, pilgrim routes, holy springs, and sites that convey mystery or great natural beauty. This last type falls into the category of mystical places: locations unconnected with established religion where, for whatever reason, some people believe that extraordinary, supernatural things can happen. The Bermuda Triangle in the western Atlantic, where airplanes and ships supposedly disappear, is a mystical place and, in effect, a vernacular culture region. Some people find the expanses of the American Great Plains mystical, and writer Jonathan Raban spoke of them as “a landscape ideally suited to the staging of the millennium, open to the gaze of the Almighty.” Sometimes the sacred space of vanished ancient religions never loses—or later regains—the functional status of mystical place, which is what has happened at Stonehenge in England.

306

307

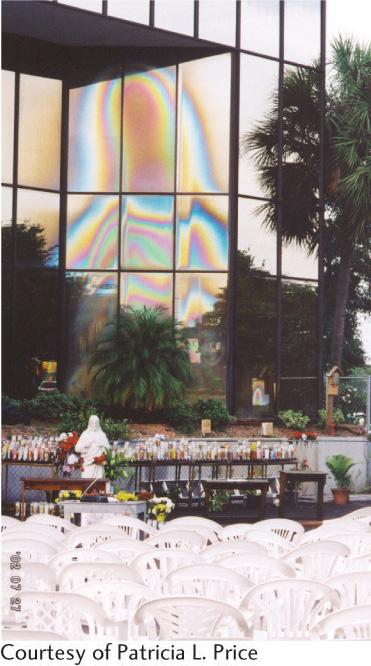

In his book The Sacred and the Profane, the renowned religious historian Mircea Eliade suggested that all societies, past and present, have sacred spaces. According to Eliade, sacred spaces are so important because they establish a geographic center on which society can be anchored. Through what he termed hierophany, a sacred space emerges from the profane, ordinary spaces surrounding it. A contemporary example of hierophany is provided by the appearance of an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on a bank building in Clearwater, Florida, transforming the profane space of finance into a Catholic pilgrimage site (Figure 7.39).

308

Patricia’s Notebook: My Travels to Jerusalem

Patricia’s Notebook

My Travels to Jerusalem

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

One of the best things about being a geographer is that I always have a good excuse to travel the world! Among the most interesting places I have visited thus far is Israel. It’s hard to think of any place on Earth where so much globally significant history, passion, and conflict are packed into such a small area. Because I’m a cultural geographer whose work emphasizes the humanistic theme of how it is that societies establish meaningful ties to places—in other words, how we dwell on Earth—I always have my eyes open for traces of meaning-making on the landscape.

In Jerusalem, for instance, you can walk the Via Dolorosa route, visiting all 14 Stations of the Cross walked by Jesus from his condemnation by the Romans to the site of his crucifixion and death. You can see the iconic golden Dome of the Rock on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, which shelters the rock (hence the name) from which Muhammad is said to have ascended to heaven. Jews also believe the site to be sacred because it is said to be the place where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac and is the site of the Western Wall, the remnant of the ancient Jewish temple. Non-Muslims are forbidden from entering the Dome of the Rock for reasons of political conflict and control as well as pollution taboos (which are held by most religions, including Islam). Some Jews voluntarily decline to set foot on the Temple Mount as well, believing it too holy for mere mortal presence.

So much of what we hear and see about this place on our nightly news depicts only the political tensions existing between Israelis and Palestinians. So it is eye-opening to wander the streets of Jerusalem and witness Jews, Christians, and Muslims, orthodox and secular alike, living their daily lives in this city (see also the World Heritage Site). Yes, there is tension. Mobility and access are sometimes blocked or at least slowed down, thanks mostly to security concerns. But, as with anyplace else on Earth, most people in Jerusalem are merely going about their business.

I always tell my students that, if given the chance to travel anywhere in the world, they should seriously consider visiting the Middle East. Directly experiencing peoples and places goes a long way toward dispelling the myths and stereotypes about those peoples and places, which are particularly prevalent in this part of the world.

World Heritage Site: Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland

World Heritage Site

The Old City of Jerusalem and Its Walls

The Old City of Jerusalem and its walls were added to the list of World Heritage Sites in 1981. The area is less than one-half of a square mile, set within modern-day Jerusalem. The old city has been occupied from the fourth millennium B.C.E., thus making Jerusalem one of the world’s oldest urban settlements (see Chapter 10). Divided into four quarters—Armenian, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim—these different “neighborhoods” were formed based on major ethnic and religious divisions dating back centuries.

◼ Greater Jerusalem holds tremendous significance to the major world religions as it is the place where Jews built and rebuilt the temple that served as a center of worship, Christ was crucified, and Mohammed ascended to heaven.

◼ The Old City includes the city’s holiest sites: the Temple Mount and the portion of the wall of the Jewish Second Temple known as the Western Wall, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Dome of the Rock. Access to these sites, some of which are off-limits to Jews, is severely contested today and is discussed further in Patricia’s Notebook, above.

◼ The Dome of the Rock pictured here is considered to be the “most contested piece of real estate on Earth” due to its religious importance. For thousands of years, Jews, Christians, and Muslims have shared Jerusalem’s city spaces— sometimes cooperatively and other times in conflict.

309

WAILING WALL: Pictured here is a portion the Jewish Second Temple that was built in 515 B.C.E. after the first temple, constructed in 957 by King Solomon, was attacked by the Egyptian pharaoh and then destroyed by the Babylonians in 586. The Second Temple, itself threatened by Greek and Roman invaders, was ultimately destroyed by the latter in 70 C.E. A remnant of the Western Wall encloses the Second Temple courtyard and is one of Judaism’s holiest sites.

◼ It is often referred to as the “Wailing Wall” because of the Jewish custom of mourning the destruction of the Second Temple at this spot. Jews pray here and place slips of paper containing written prayers inside the crevices of the wall. More than 1 million notes are placed within the wall’s crevices each year, and some organizations allow the faithful to e-mail notes that are later placed within the wall.

◼ As with holy sites from many faiths, the Wailing Wall is segregated by gender. Men visit one side, while women and children are restricted to a much smaller and crowded portion of the wall on the right-hand side.

◼ Some women argue that ultra-Orthodox restrictions against women and men sharing the same space in places of worship illegally restrict women’s right to space, and that bans against women wearing prayer garments and reading aloud from the Torah at the Wall are unconstitutional under Israeli law.

TOURISM: Jews, Christians, and Muslims have for millennia shared Jerusalem’s city spaces in ways that involve cooperation as well as conflict. Its streets, apartments, and public spaces bustle with nearly 1 million inhabitants of diverse faiths and ethnicities going about their daily lives. It is fascinating to experience the mixture of language, dress, and customs interacting in Jerusalem.

◼ In addition, 3.5 million tourists visit every year—roughly 4 times the city’s resident population. Given the number of religious sites in Jerusalem, pilgrimage alone accounts for many tourist visits. The country of Israel, where Jerusalem is located, is also home to many sites of historical, archaeological, cultural, and religious significance, as well as being near picturesque Mediterranean beaches and the greater Middle Eastern region.

◼ In 1982 Jerusalem’s Old City and Walls were placed on the list of World Heritage Sites in danger, due in part to the deterioration and damage stemming from tourism and a lack of adequate conservation efforts. In other words, Jerusalem’s Old City is literally in danger of being loved to death.

◼ Approximately 3 million tourists each year

◼ Divided into four quarters: Armenian, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim

◼ Home to key holy sites: The Temple Mount and Western Wall, Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Dome of the Rock

◼ Sometimes a site of conflict due to shared religious spaces

310