GLOBALIZATION

8.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe how the processes of globalization alter the geography of agriculture.

For most of human history, people obtained their provisions locally and maintained their own distinct dietary cultures. The development of global markets over the past 500 years has shifted cultural food preferences and altered the ecology of vast areas of the planet.

LOCAL-GLOBAL FOOD PROVISIONING

As European maritime explorers brought far-flung cultures into contact, a multitude of crops were diffused around the globe. The processes of exploration, colonization, and globalization created new regional cuisines (imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes from the Americas) and at the same time simplified the global diet to a disproportionate reliance on only three grains: wheat, rice, and maize.

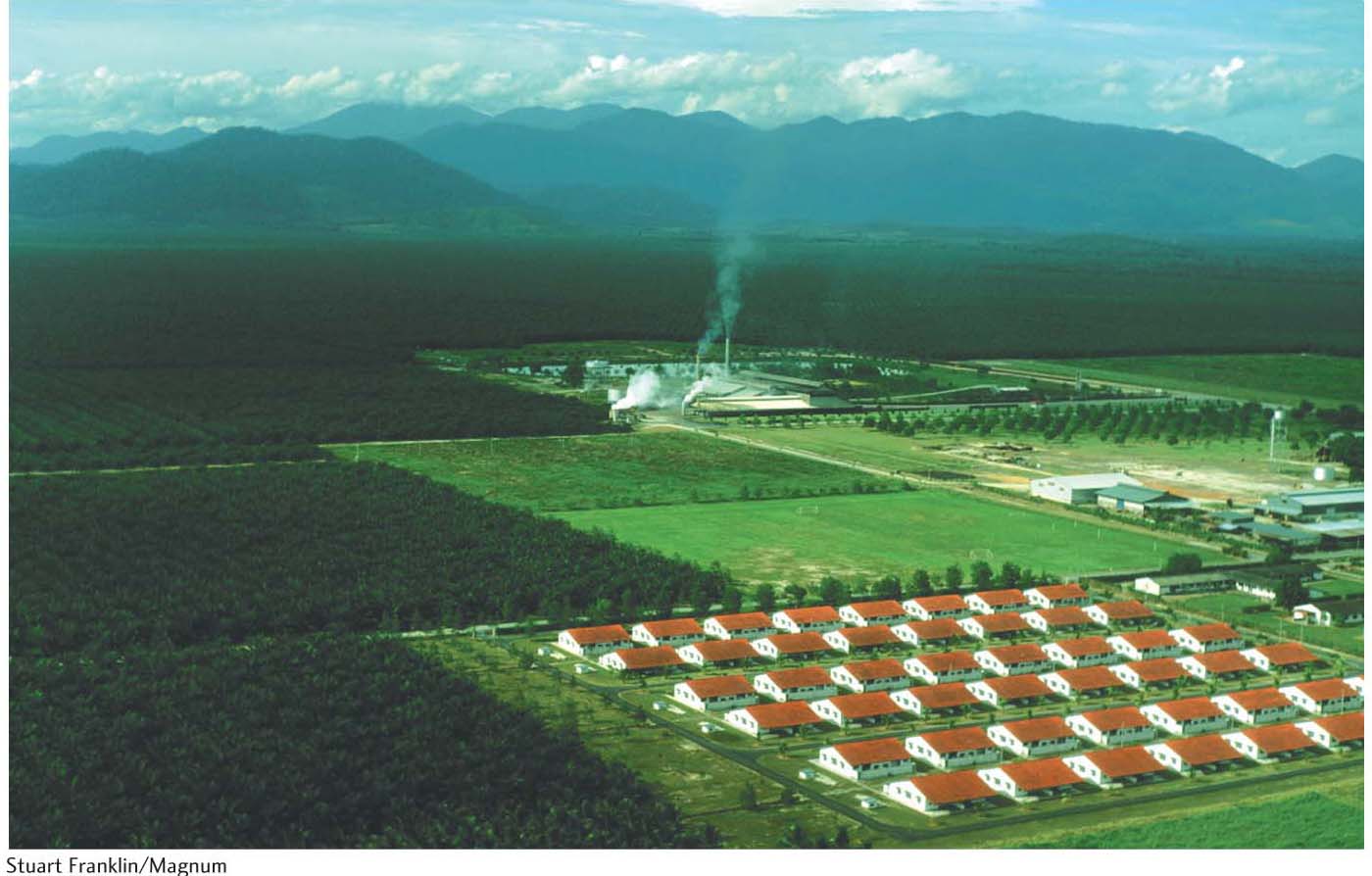

The expansion of European empires in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was inseparable from the expansion of tropical plantation agriculture. Plantations in warm climates produced what were then luxury foods for markets in the global North, which had developed seemingly insatiable appetites for sugar, tea, coffee, and other tropical crops. The expansion of plantation agriculture had profound effects on local ecology, all but obliterating, for example, the forests of the Caribbean and the tropical coasts of the Americas (Figure 8.20).

336

In short, we have witnessed the development of a global food system that, for better or worse, has freed consumers in the affluent regions of the world from the constraints of local ecologies. Fresh strawberries, bananas, pears, avocados, pineapples, and many, many other types of temperate, subtropical, and tropical produce are available in our urban supermarkets any day, any time of the year. On the other hand, the emphasis on a relatively small number of staple crops desired by northern consumers can mean the abandonment of local crop varieties and a decline in the associated biological diversity. Imported refined wheat from the global North enters poor tropical countries by the shipload, altering local dietary cultures and undercutting the ability of local farmers to sell their crops at a profitable price.

These are the general patterns, but the globalization of food and agriculture has complex effects on culture and ecology that vary by location and spatial scale. These complexities are best illustrated by a case study from the Peruvian Andes. Geographer Karl Zimmerer (see Rod’s Notebook for a different look at the globalization of food and agriculture) conducted extensive fieldwork among Quichua peasant farmers in the Paucartambo Andes to determine the effects of economic change on indigenous agricultural practices and the genetic diversity of local crops. He wanted to test the general hypothesis that as globalization and national economic policies integrate indigenous farmers into market production, the diversity of crops declines, ultimately resulting in genetic erosion (i.e., a decline in the genetic diversity of cultivars).

Zimmerer’s study produced surprising findings on the complex relationships among culture, economy, and the environment. On the question of whether farmers must abandon crop diversity in order to adopt new, commercially oriented high-yielding varieties, he found there was no simple answer. In fact, it was the more well-off peasants, heavily involved in commercial farming, who had the resources and land to cultivate diverse crops and “enjoy their agronomic, culinary, cultural, and ritual values.” Among these values was the use of diverse, noncommercial potato varieties in local bartering. The ability to use noncommercial varieties in this way is valued in the local culture because it is a traditional way to cement interpersonal bonds. Such uses emphasize the cultural importance of crop diversity. Zimmerer discovered that the cultural relevance of crops was a strong motivation for planting by well-off farmers. At least 90 percent of the genetically diverse crops had been conserved, even as the Quichua were further integrated into commercial production for the market.

A number of lessons can be drawn from Zimmerer’s study, chief among them the need to carefully examine the effects of globalization on culture and environment, rather than simply assuming that local agricultural practices will give way to the demands of the marketplace. The Quichua farmers who benefited most from their participation in the market were those best able to cultivate traditional varieties, which functioned as an expression of cultural identity and their sense of place. Cultural values, not merely a strict economic or ecological calculus, critically influenced farming decisions.

337

Rod’s Notebook: The Importance of Place in the Global Food System

Rod’s Notebook

The Importance of Place in the Global Food System

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

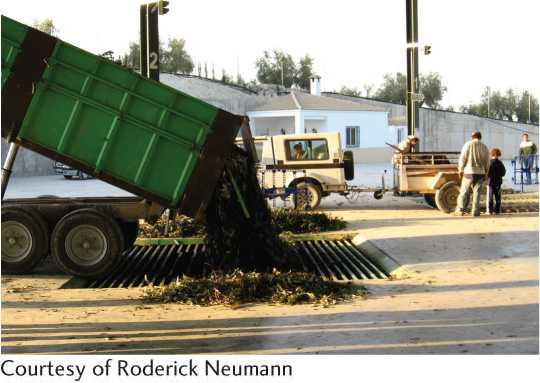

December is olive harvest season in southern Spain, when farmers large and small bring their crops to nearby mills for processing. On a recent research trip to Jaén Province in southern Spain, my colleague Gail Hollander and I observed the process at the mill of the Sierra de Cazorla Olive Growers’ Cooperative. We watched as families with 5-foot tow trailers lined up next to huge corporate-owned dumptrucks to unload their harvests onto 150-foot conveyer belts leading to the oil presses. We were witnessing a centuries-old harvest ritual refitted to agroindustrial mass production.

Olives and olive oil are staple foods in the Mediterranean diet. Thus, people in the region are sensitized to varying tastes, colors, and consistencies of olive oils to which most North Americans are oblivious. Approach most North Americans about olive oil and they are likely to respond with something like, “Italian food.” In one sense, this is correct, since Italy is indeed the largest exporter of processed olive oil. But Spain is the world’s largest producer of olives, the greatest share coming from Jaén Province. Most of Spain’s harvest, however, is sent to Italy for repackaging and export under Italian brand names that are more familiar to North American shoppers.

This system of mass production of olive oil for Italian export firms worked well for Spanish farmers until recent years. The forces of globalization are now challenging Spain’s dominance of the market. North African countries, such as Tunisia, are expanding olive production and competing with Spain for access to the global mass market of undifferentiated oil. In interviews with farmers in Jaén, we discovered that they are looking for ways to differentiate their product from mass-produced oils. Similar to the way fine wines are marketed, they seek to emphasize the unique qualities of oils that are produced in specific places with particular climate and soil characteristics. The idea is to find a niche market of high-end consumers who are appreciative of the distinct qualities and characteristics of local olive varieties.

Jaén farmers have responded to the challenges of globalization by creating new place-based products. Olive oil is being bottled with denominación de origen labeling, a third-party certification system that guarantees consumers that the product originates from a specific place. We discovered that the number of marketing cooperatives using the denominación de origen designation has exploded across Jaén. Each co-op offers an array of olive-based products. We are still enjoying, for example, our bottle of extra-virgin Royal Aniversario 10 olive oil from the Sierre de Cazorla denominación de origen, a product that many Spaniards consider to be of the highest quality anywhere. Currently, denominación de origen olive oil is sold mostly to an appreciative domestic Spanish market. Farmers are eyeing North America and East Asia as future export markets as affluent consumers learn of the complexities of olive oil quality and seek new culinary experiences. We were reminded that place matters in the global food system.

338

THE VON THÜNEN MODEL

Geographers and others have long tried to understand the distribution and intensity of agriculture based on transportation costs to market. Long before globalization took hold, the nineteenth-century German scholar-farmer Johann Heinrich von Thünen developed a core-periphery model to address the problem. In his model, von Thünen proposed an “isolated state” that had no trade connections with the outside world; possessed only one market, located centrally in the state; had uniform soil and climate; and had level terrain throughout. He further assumed that all farmers located the same distance from the market had equal access to it and that all farmers sought to maximize their profits and produced solely for market. Von Thünen created this model to study the influence of distance from market and the concurrent transport costs on the type and intensity of agriculture.

core-periphery

A concept based on the tendency of both formal and functional culture regions to consist of a core or node, in which defining traits are purest or functions are headquartered, and a periphery that is tributary and displays fewer of the defining traits.

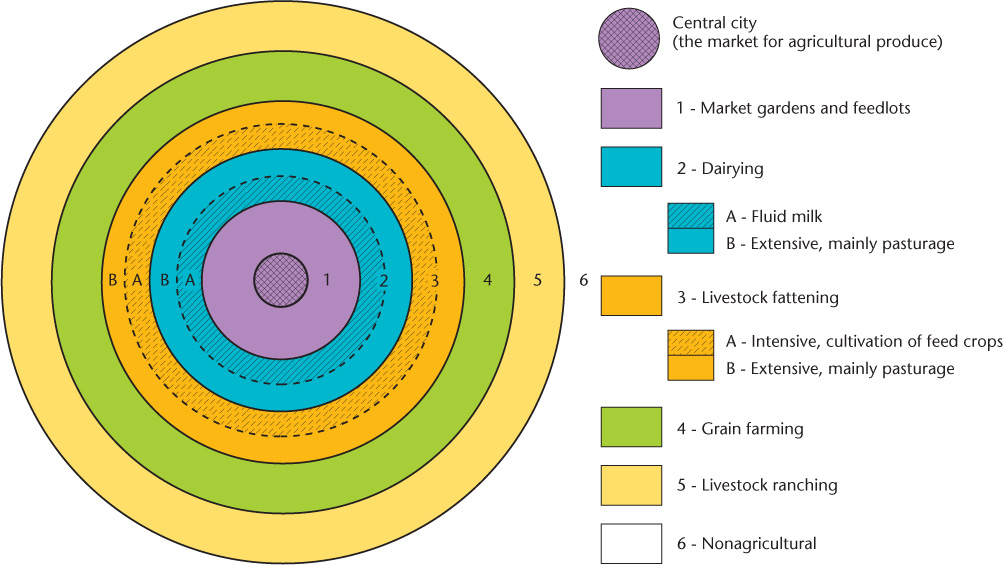

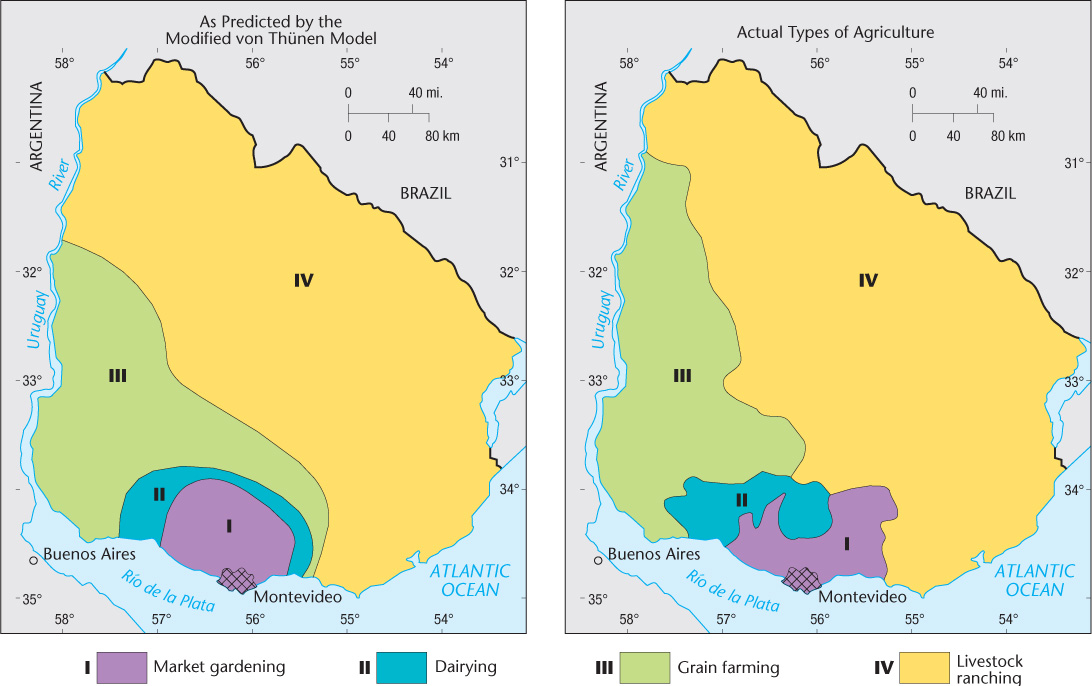

Figure 8.21 presents a modified version of von Thünen’s isolated-state model, which reflects the effects of improvements in transportation since the 1820s, when von Thünen proposed his theory. The model’s fundamental feature is a series of concentric zones, each occupied by a different type of agriculture, located at progressively greater distances from the central market.

For any given crop, the intensity of cultivation declines with increasing distance from the market. Farmers near the market have minimal transportation costs and can invest most of their resources in labor, equipment, and supplies to augment production. Indeed, because their land is more valuable and subject to higher taxes, they have to farm intensively to make a bigger profit. With increasing distance from the market, farmers invest progressively less in production per unit of land because they have to spend progressively more on transporting produce to market. The effect of distance means that highly perishable products such as milk, fresh fruit, and garden vegetables need to be produced near the market, whereas peripheral farmers have to produce nonperishable products or convert perishable items into a more durable form, such as cheese or dried fruit.

339

The concentric-zone model describes a situation in which highly capital-intensive forms of commercial agriculture, such as market gardening and feedlots, lie nearest to market. The increasingly distant, successive concentric belts are occupied by progressively less intensive types of agriculture, represented by dairying, livestock fattening, grain farming, and ranching.

How well does this modified model describe reality? As we would expect, the real world is far more complicated. For example, the emergence of cool chains for agricultural commodities—the refrigeration and transport technologies that bring fresh produce from fields around the globe to our dinner tables—have collapsed distance. Still, on a world scale, we can see that intensive commercial types of agriculture tend to occur most commonly near the huge urban markets of northwestern Europe and the eastern United States. An even closer match can be observed in smaller areas, such as in the South American nation of Uruguay (Figure 8.22).

cool chain

The refrigeration and transport technologies that allow for the distribution of perishables.

The value of von Thünen’s model can also be seen in the underdeveloped countries of the world. Geographer Ronald Horvath made a detailed study of the African region centering on the Ethiopian capital city of Addis Ababa. Although noting disruptions caused by ethnic and environmental differences, Horvath found “remarkable parallels between von Thünen’s crop theory and the agriculture around Addis Ababa.” Similarly, German geographer Ursula Ewald applied the model to the farming patterns of colonial Mexico during the period of Spanish rule, concluding that even this culturally and environmentally diverse land provided “an excellent illustration of von Thünen’s principles on spatial zonation in agriculture.”

340

WILL THE WORLD BE FED?

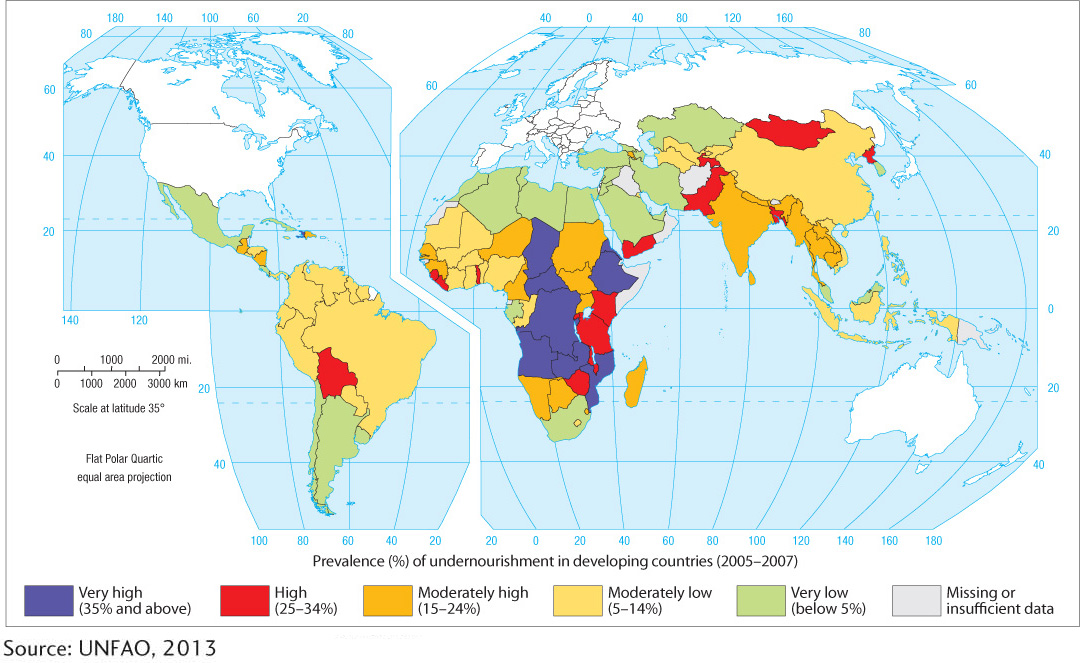

Are famine and starvation inevitable as the world’s population grows, as Thomas Malthus predicted (see Chapter 3)? Or, will our agricultural systems successfully feed nearly 7 billion people? In trying to answer these questions, we face a paradox. Today, nearly 1 billion people are malnourished, some to the point of starvation. Almost every year, we read of food shortages occurring somewhere in the world. In 2008 there were food riots in 30 countries around the world when food prices shot beyond the reach of hundreds of thousands of the urban poor. Between 1990 and 2010, the number of hungry people in western and southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa increased by tens of millions (Figure 8.23).

Yet—and this would astound Malthus—food production has grown more rapidly than the world population over the past 50 or 60 years. Per capita, more food is available today than in 1950, when fewer than half as many people lived on Earth. Production continues to increase. From 1996 to 2006, world food production increased at an annual rate of 2.2 percent, and hunger was reduced by 30 percent in more than 30 countries. Global projections foresee continuing annual production increases of 1.5 percent through 2030. Thus, paradoxically, on a global scale there is enough food produced to feed everyone, while famines and malnutrition prevail. If the world food supply is sufficient to feed everyone and yet hunger afflicts one of every six or seven persons, then Malthus was wrong about the limits on population growth but right about the persistence of deprivation.

341

What explains this paradox of dearth amidst plenty? As geographer Thomas Bassett and economist Alex Winter-Nelson show in their Atlas of World Hunger, one must ask both where and why people are hungry. We see in Figure 8.23 where people are going hungry on a global scale. Why they are hungry is complex and varies geographically and historically. For example, Bassett and Winter-Nelson explain that the crisis of HIV/AIDS in southern Africa affects mostly 15- to 49-year-olds, the most productive segment of the population. The epidemic thus negatively affects food production and raises the level of food insecurity, especially in rural areas.

To a great extent, international political economics, not global food shortages, causes hunger and starvation. International trade favors the farmers of wealthier countries through systems of government subsidies that keep the prices of their agricultural exports artificially low. Third World farmers find it difficult to compete. Many Third World countries do not grow enough food to feed their populations, and they cannot afford to purchase enough imported food to make up the difference. As a result, famines can occur even when plenty of food is available. Millions of Irish people starved in the 1840s while the adjacent nation of Great Britain possessed enough surplus food to have prevented this catastrophe. Bangladesh suffered a major famine in 1974, a year of record agricultural surpluses in the world.

Internal government policies are also an important cause of famine. The roots of the largest famine of the twentieth century may be traced to the agricultural policies of the Chinese government’s 1958-1961 Great Leap Forward. The Chinese government required peasants to abandon their individual fields and work collectively on large, state-run farms. This policy of collectivization succeeded in boosting food production in some cases but failed in most. Thirty million rural Chinese died of starvation during the Great Leap Forward. Misguided government policies triggered one of the first famines of the twenty-first century as well. In the early 2000s, Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe clung to power by demonizing white commercial farmers. In 2002 he threatened Zimbabwe’s commercial farmers with imprisonment if they continued to farm. Other government policies discouraged planting and cultivation, thus producing another human-caused famine.

Even when major efforts are made to send food from wealthy countries to famine-stricken areas, the poor transportation infrastructure of Third World countries often prevents effective distribution. Political instability can disrupt food shipments, and the donated food often falls into the hands of corrupt local officials. Such was the case in Somalia during the famine of 2011-2012, where warring factions prevented food aid from reaching starving populations. Over one-quarter of a million people died needlessly during that period of drought. So while the trigger for famine may be environmental, there are frequently deep-seated political and economic problems that conspire to block famine relief.

THE GROWTH OF AGRIBUSINESS

Globalization and its impact on agriculture have been referred to throughout this chapter. Globalization, you will recall, involves the restructuring of the world economy by multinational corporations thriving in an era of free-trade capitalism, rapid communications, improved transport, and computer-based information systems. When applied to agriculture, globalization tends to produce agribusiness: a modern farming system that is totally commercial, large-scale, mechanized, and dependent upon chemicals, hybrid seeds, genetic engineering, and the practice of monoculture (raising a single specialty crop on vast tracts of land). Furthermore, agribusinesses are often vertically integrated; that is, corporations own the land as well as the processing and marketing facilities. Vertical integration takes a variety of forms depending on the nature of production processes and markets. The case of the “global chicken” provides a useful illustration of vertically integrated agribusiness as well as the interconnections of changing cultural values and global food production.

globalization

The binding together of all the lands and peoples of the world into an integrated system driven by capitalistic free markets, in which cultural diffusion is rapid, independent states are weakened, and cultural homogenization is encouraged.

agribusiness

Highly mechanized, large-scale farming, usually under corporate ownership.

monoculture

The raising of only one crop on a huge tract of land in agribusiness.

342

The origins of the “global chicken” can be found in the shift from beef to poultry as the preferred protein source in American dietary culture, which underwent fundamental changes during the post-World War II period. From 1945 to 1995, per-capita consumption of chicken in the United States rose from 5 to 70 pounds (2.25 to 31.5 kilograms), and by 1990 it had surpassed that of beef. This was a startling development in American culture, where the myth of the cowboy herding cattle on the open range has been so central to an imagined national identity. Since the 1990s, the per-capita consumption of chicken has continued to grow as that of beef continues to decline, especially following the publicity about mad cow disease.

Advances in U.S. agrotechnologies for the breeding, nutrition, housing, and processing of chickens largely account for increases in production efficiency (Figure 8.24). This has allowed the U.S. poultry industry, largely centered in the South, to become the world’s single largest supplier of broilers. As the taste for chicken spread worldwide, U.S. producers gained an increasing share of an expanding global market. In the last decades of the twentieth century, world trade in broilers grew nearly 500 percent, while the U.S. share of that trade doubled. China has been the hottest import market, because rising affluence there has led to increasing per-capita consumption. At the same time, China, along with Brazil, Turkey, and Japan, is increasing its production and its exports of poultry. Thus, U.S. share of the global market has shrunk in the twenty-first century even as per-capita poultry consumption continues to rise worldwide.

Farmers who produce a single commodity, such as poultry, must produce far more than the local market can consume in order to be profitable. They must therefore sell in both national and global markets, access to which requires a dependence on multinational agribusinesses. So pervasive is the reach of agribusiness that many poultry farmers no longer own the chickens they produce; multinational corporations do. Farmers contract with multinationals to receive farm inputs such as chicks and feed and to cover other expenses related to marketing and transport. When the chickens mature, they are trucked to the contracting corporation’s processing plant where they are weighed and corporate expenditures are deducted from the farmer’s shares. The farmers take their earnings to pay the mortgages on their lands and buildings, and the chickens are processed for the global food system.

THE ONGOING GREEN REVOLUTION

The green revolution generally refers to the transfer of agroindustrial technological packages to Third World countries. It can also been seen as one component of agricultural globalization, along with countless “rural development” projects in Third World countries, usually funded by the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. These projects often displace small-scale peasant farmers to make way for larger enterprises and even multinational agribusinesses. The green revolution is thus a continuation and geographic expansion of the industrialization of agriculture. Key to the industrialization process are seeds, which are the foundation of cultivation. Whoever controls seeds controls access to the next crop harvest.

343

Control of seeds has been consolidated in fewer and fewer companies. The five biggest hybrid vegetable seed suppliers control 75 percent of the global market, and the ten largest agrochemical manufacturers command 85 percent of the world supply. Four corporations supply more than two-thirds of the U.S. consumption of hybrid seed maize. Sometimes single companies—Monsanto, for example—both supply the seeds and manufacture the pesticides. What’s more, the genetic engineering of seeds is often done in-house. This arrangement allows Monsanto to genetically engineer “Roundup Ready” seed varieties. Roundup is an herbicide manufactured by Monsanto, and its Roundup Ready gene builds in greater tolerance to higher doses. The seeds essentially became vehicles to sell more herbicide.

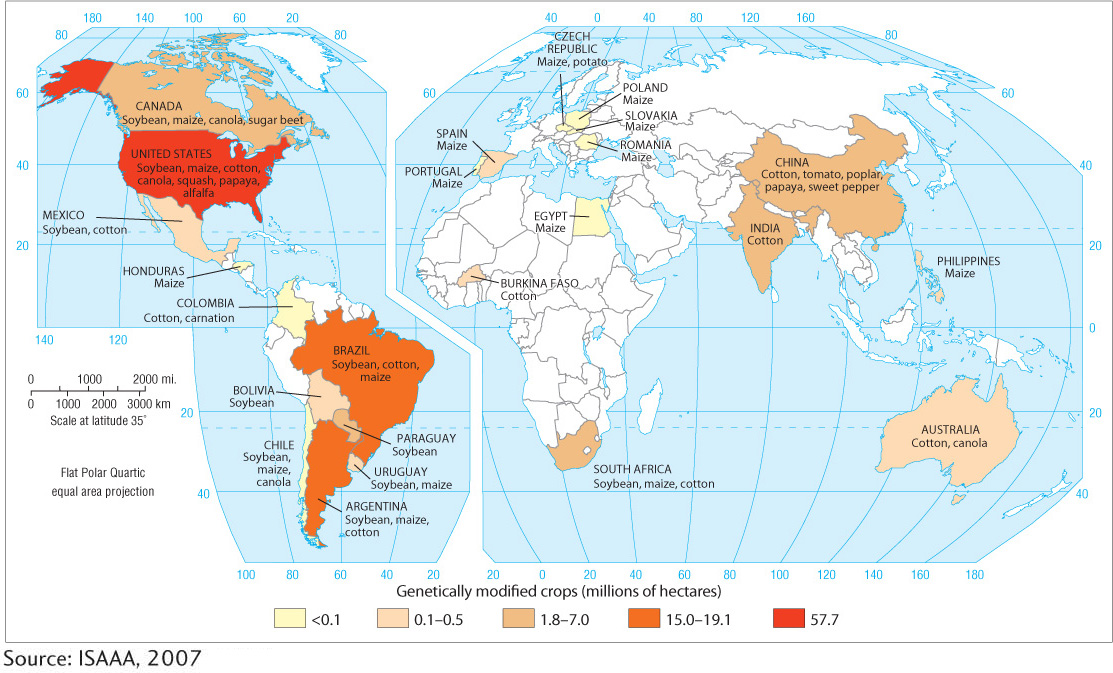

Genetically modified (GM) crops, the products of biotechnology, are seen by many as another aspect of globalization. Genetic engineering produces new organisms through gene splicing. Pieces of DNA can be recombined with the DNA of other organisms to produce new properties, such as pesticide tolerance or disease resistance. DNA can be transferred between not only species but also plants and animals, which makes this technology truly revolutionary and unlike any other development since the beginning of domestication. Agribusinesses are often able to patent the processes and resulting genetically engineered organisms and, thus, claim legal ownership of new life-forms.

genetically modified (GM) crops

Plants whose genetic characteristics have been altered through recombinant DNA technology.

Political, economic, and environmental problems resulting from the concentration of ownership of seeds and the production of pesticide-resistant GM seeds are beginning to emerge in the United States. The Department of Justice began an antitrust investigation of Monsanto’s activities in the seed market. One reason for the investigation was the sharp rise in corn and soybean seed prices, which have more than doubled since 2001. The use of Roundup Ready seeds has resulted in the emergence and spread of so-called superweeds, weeds that have evolved resistance to increasing doses of Roundup herbicide. Thus, the gains in yield initially produced by Roundup Ready seeds are starting to decline, suggesting the environmental limitations of GM seeds that promote the use of pesticides.

Commercial production of GM crops began in the United States in 1996. The technology has now spread around the globe, but the United States still dominates, accounting for two-thirds of the world’s acreage (Figure 8.25). Two crops, soybeans and corn, account for the rapid growth of GM food production in the United States. By 2010, 93 percent of all soybeans and 86 percent of all corn produced in the United States were genetically modified. Their genetically engineered resistance to disease and drought are an important reason for the spread of GM crops, but that’s only part of the story. For example, all of the GM soybean seeds in the United States are engineered to tolerate greater doses of synthetic herbicides produced by agrochemical companies.

If you provision your household from a U.S. supermarket, you have undoubtedly ingested GM foods. Whether or not one finds this troubling is closely related to the strength of certain cultural norms and values that vary from region to region and country to country. In England and western Europe, where national identities are strongly linked to the countryside, agrarian culture, and regional cuisines, there has been a lot of opposition to biotechnology in agriculture. In response to public pressure, major supermarket chains, such as Sainsbury’s in England, have refused since 1998 to sell GM foods. In the United States, the response has been far more muted, so much so that the expansion of GM crop planting has proceeded virtually without public debate. These cultural differences are now coming to the fore of globalization debates as the European Union challenges the United States over international trade in GM seeds and foods.

344

FOOD FEARS

A globalized food system is vulnerable to events that threaten food safety. Globally significant events, such as the 1990s outbreaks of mad cow disease in Great Britain that shut down the country’s export of live cattle and devastated consumer demand for beef, make international headlines. Likewise, national-level recalls of contaminated foods in the United Seat es seem to be in the news almost daily. News of disease outbreaks, some life-threatening, has raised anxiety levels among consumers about eating food transported from distant: places. Responses to such crises in the global food system vary culturally and individually and may be based more on the perception of risk than on the probability of illness or death. The way in which national governments and consumers respond to a particular food safety problem can fundamentally reshape geographic patterns of agricultural production on a global scale. Conversely, the idea that a culturally symbolic food may be tainted and life-threatening can shake the strongest of cultural identities. For example, the case of mad cow disease in Great Britain—where beef and dairy production and consumption have long been associated with British cultural identity—challenged culturally defined notions of a proper British meal.

There have been many more cases of foodborne disease outbreaks around the world since mad cow disease made headlines. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has responded by taking on a larger role in monitoring and investigating foodborne outbreaks—illnesses that occur when two or more people consume the same food or drink. CDC records show the most frequent contaminants are various genetic strains and species of common viruses and bacteria, principally the bacteria Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli (abbreviated as E. coli) and the viruses hepatitis A and norovirus. Infections can result in hospitalization and even death, mostly in the cases of children, the elderly, and the infirm. Salmonella infections are the single largest source of fatalities.

foodborne outbreaks

When two or more people acquire the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink.

345

Ironically, many of the most common foodborne outbreaks occur in what nutritionists consider the basics of a healthy diet—fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, and lean protein sources such as chicken and fish. In particular, pre-packaged leafy greens have repeatedly been implicated in outbreaks of E. coli and Salmonella. In 2012 mixed greens from a Massachusetts grower infected 33 people in 5 states with E. coli. In 2013 Taylor Farms, a giant grower with multiple processing facilities in the United States and Mexico, recalled from 39 states its baby green spinach, which was potentially contaminated with E. coli (Figure 8.26). Such preemptive recalls are becoming commonplace. Taylor Farms conducted three recalls in 2011 and three again in 2012. The growth in consumer demand for fresh produce combined with the consolidation and centralization of food production leads to increased incidents, outbreaks, and recalls.

The centralization and globalization of food production systems have made foodborne outbreaks both more common and difficult to control. Take the case of a 2013 outbreak of hepatitis A in 10 U.S. states that afflicted 161 people coast to coast, of whom 70 were hospitalized. The product common to all cases was “Townsend Farms Organic Antioxidant Blend.” The strain of hepatitis A was identified as common in the Middle East and North Africa. Using this genetic clue and information about the geographic origins of the product’s component ingredients, investigators narrowed the likely source to pomegranate seeds from a global exporter in Turkey. The location of the seeds’ production has not been identified, but the CDC noted that a similar outbreak in Europe was traced to seeds grown in Egypt. This case illustrates how the growing complexity of the global food system both increases consumer choice while simultaneously exposing consumers to risks that transcend national borders.

A final case illustrates how under globalization the dangers of foodborne outbreaks can alter agricultural practices in far-flung parts of the world. Disproportionately high levels of Salmonella contamination have been discovered in common spices found in kitchens worldwide. A 2010 outbreak that sickened 250 in the United States, for example, was traced to red and black pepper. India is the world’s largest spice producer and has been for centuries, so it is vulnerable to huge economic losses when such outbreaks occur. Responding to Salmonella outbreaks, the Indian government has mandated changes in the way pepper is harvested and processed. The costs of the changes are out of reach for many farmers, prompting the government to issue subsidies and organize grower cooperatives.

The cases of foodborne disease outbreaks demonstrate the global interconnectivity of food-producing and food-consuming regions, the vulnerability of the global food system, and the role of cultural norms and values surrounding questions of food safety.

346