CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

8.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Relate how agriculture is expressed within the cultural landscape.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, 37.3 percent of the world’s land area is cultivated or pastured. In this huge area, the visible imprint of humankind might best be called the agricultural landscape. The agricultural landscape often varies even over short distances, telling us much about local cultures and subcultures. Moreover, it remains in many respects a window on the past, and archaic features abound. For this reason, the traditional rural landscape can teach us a great deal about the cultural heritage of its occupants.

agricultural landscape

The cultural landscape of agricultural areas.

In Chapter 3, we discussed some aspects of the agricultural landscape, in particular the rural settlement forms. We saw the different ways in which farming people situate their dwellings in various cultures. In Chapter 2, we considered traditional rural architecture, another element in the agricultural landscape. In this chapter, we attend to a third aspect of the rural landscape: the patterns of fields and property ownership created as people occupy land for the purpose of farming.

SURVEY, CADASTRAL, AND FIELD PATTERNS

A cadastral pattern is one that describes property ownership lines, whereas a field pattern reflects the way that a farmer subdivides land for agricultural use. Both can be greatly influenced by survey patterns, the lines laid out by surveyors prior to the settlement of an area. Major regional contrasts exist in survey, cadastral, and field patterns, for example, unit-block versus fragmented landholding and regular, geometric survey lines versus irregular or unsurveyed property lines.

cadastral pattern

The shapes formed by property borders; the pattern of land ownership.

survey pattern

A pattern of original land survey in an area.

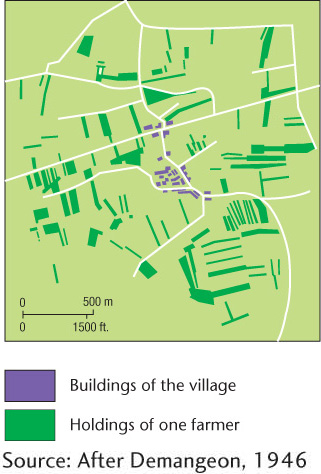

Fragmented farms are the rule in the Eastern Hemisphere. Under this system, farmers live in farm villages or smaller hamlets. Their landholdings lie splintered into many separate fields situated at varying distances and lying in various directions from the settlement. One farm can consist of 100 or more separate, tiny parcels of land (Figure 8.33). The individual plots may be roughly rectangular in shape, as in Asia and southern Europe, or they may lie in narrow strips. The latter pattern is most common in Europe, where farmers traditionally worked with a bulky plow that was difficult to turn. The origins of the fragmented farm system date back to an early period of peasant communalism. One of its initial justifications was a desire for peasant equality. Each farmer in the village needed land of varying soil composition and terrain. Travel distance from the village was to be equalized. From the rice paddies of Japan and India to the fields of western Europe, the fragmented holding remains a prominent feature of the cultural landscape.

hamlet

A small rural settlement, smaller than a village.

357

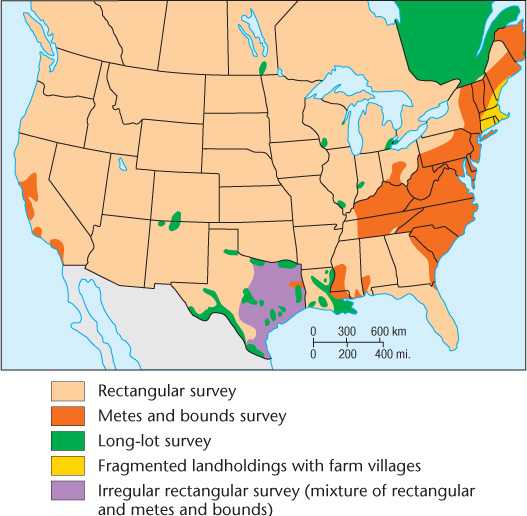

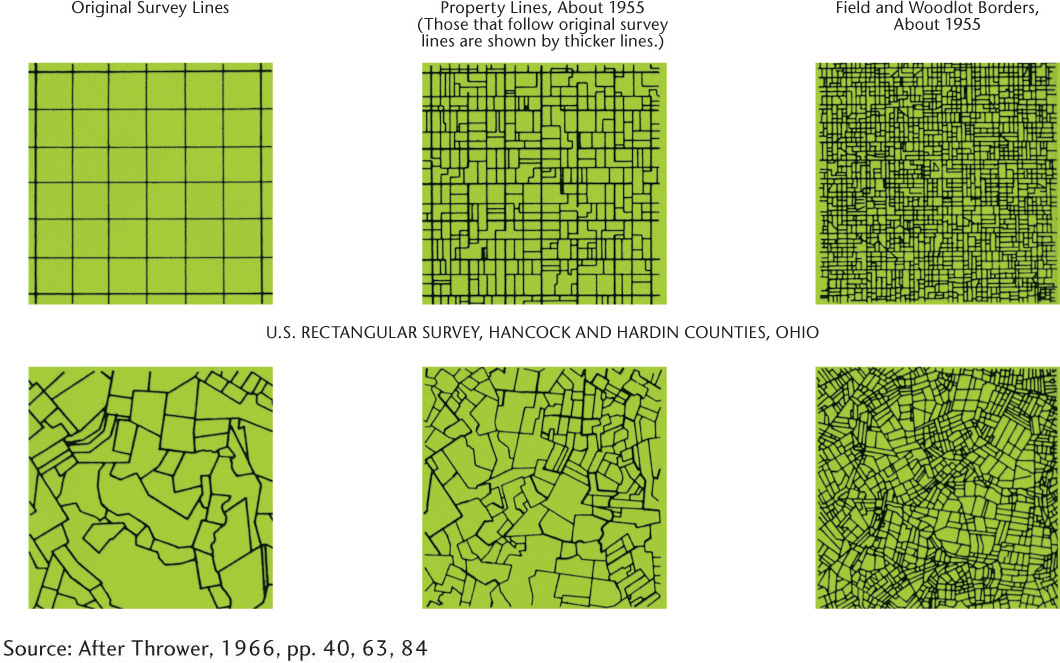

Unit-block farms, by contrast, are those in which all of the farmer’s property is contained in a single, contiguous piece of land. Such forms are found mainly in the overseas area of European settlement, particularly the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Most often, they reveal a regular, geometric land survey. The checkerboard of farm fields in the rectangular survey areas of the United States provides a good example of this cadastral pattern (Figure 8.34).

358

The American township and range system, discussed in Chapter 6, first appeared after the Revolutionary War as an orderly method for parceling out federally owned land for sale to pioneers. It imposed a rigid, square, graphpaper pattern on much of the American countryside; geometry triumphed over physical geography (Figure 8.35). Similarly, roads follow section and township lines, adding to the checkerboard character of the American agricultural landscape. Canada adopted an almost identical survey system, which is particularly evident in the Prairie Provinces.

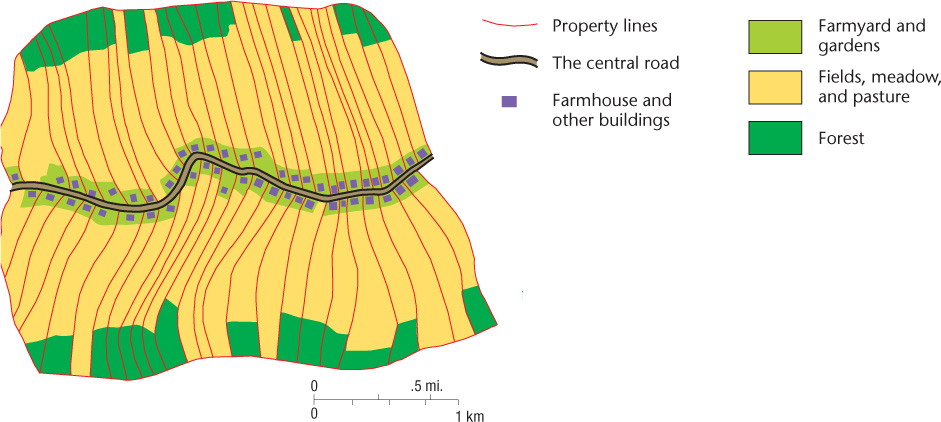

Equally striking in appearance are long-lot farms, where the landholding consists of a long, narrow unit block stretching back from a road, river, or canal (Figure 8.36). Long lots lie grouped in rows, allowing this cadastral survey pattern to dominate entire districts. Long lots occur widely in the hills and marshes of central and western Europe, in parts of Brazil and Argentina, along the rivers of French-settled Québec and southern Louisiana, and in parts of Texas and northern New Mexico. These unit-block farms are elongated because such a layout provides each farmer with fertile valley land, water, and access to transportation facilities, either roads or rivers. In French America, long lots appear in rows along streams, because waterways provided the chief means of transport in colonial times. In the hill lands of central Europe, a road along the valley floor provides the focus, and long lots reach back from the road to the adjacent ridge crests.

Some unit-block farms have irregular shapes rather than the rectangular or long-lot patterns. Most of these result from metes and bounds surveying, which makes much use of natural features such as trees, boulders, and streams. Parts of the eastern United States were surveyed under the metes and bounds system, with the result that farms there are much less regular in outline than those where rectangular surveying was used (Figure 8.37).

359

subject To Debate: CAN BIOFUELS SAVE THE PLANET?

Subject To Debate

CAN BIOFUELS SAVE THE PLANET?

In 2005, in response to diminishing oil reserves and global warming, the U.S. government mandated that biofuels be added to gasoline. Governments around the world have implemented similar initiatives to increase renewable fuel use. Globally, the most promising environmental outcome of increased biofuel use is a decrease in greenhouse gasses. Growing plants consume atmospheric carbon dioxide. Using them for fuel thus recycles an important greenhouse gas, in contrast with fossil fuels, which release stored carbon into the atmosphere when combusted.

Biofuel demand is transforming agriculture around the world, but the energy and environmental benefits are uncertain. Because U.S. corn cultivation is so thoroughly industrialized, ethanol production consumes as much fossil fuel as it replaces. By some estimates, corn ethanol production uses more energy than it supplies. Brazil’s sugarcane ethanol industry has a far better energy balance of 1 unit of fossil fuel input to 8 units of biofuel output. These energy gains may be offset by other environmental costs. Sugarcane cultivation has created a monocultural desert that is expected to double in acreage by 2014. Many fear this will contribute to deforestation. Likewise, in the United States, portions of 35 million acres of land set aside for soil and wildlife conservation have been plowed to grow corn for ethanol.

Continuing the Debate

Contemplate the future role biofuels will play in addressing the linked crises of energy supply and global warming and consider these questions:

•What do you think can be done to make biofuels more promising environmentally?

•How can food security for the poor be assured as biofuel use increases?

•Who do you think will benefit the most from the expansion of biofuel use? Small farmers or agribusiness? High-income countries or low-income countries? Consumers or corporations?

360

FENCING AND HEDGING

Property and field borders are often marked by fences or hedges, heightening the visibility of these lines in the agricultural landscape. Open-field areas, where the dominance of crop raising and the careful tending of livestock make fences unnecessary, still prevail in much of western Europe, India, Japan, and some other parts of the Eastern Hemisphere, but much of the remainder of the world’s agricultural land is enclosed.

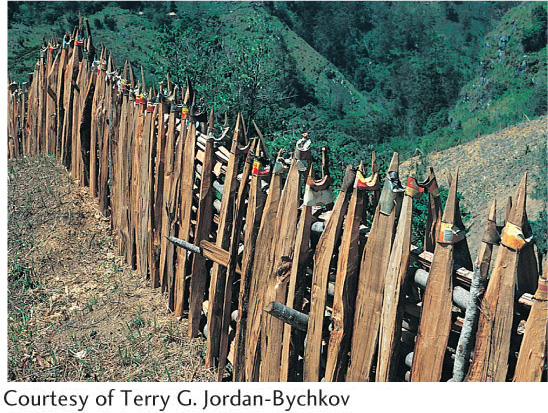

Fences and hedges add a distinctive touch to the cultural landscape (Figure 8.38). Because different cultures have their own methods and ways of enclosing land, types of fences and hedges can be linked to particular groups. Fences in different parts of the world are made of substances as diverse as steel wire, logs, poles, split rails, brush, rock, and earth. Those who visit rural New England, western Ireland, or the Yucatán Peninsula will see mile upon mile of stone fence that typifies those landscapes. Barbed-wire fences swept across the American countryside a century ago, but remnants of older styles can still be seen. In Appalachia, the traditional split-rail zigzag fence of pioneer times survives here and there. As do most visible features of culture, fence types can serve as indicators of cultural diffusion.

The hedge is a living fence. In Brittany and Normandy in France and in large areas of Great Britain and Ireland, hedgerows are a major aspect of the rural landscape (Figure 8.39). To walk or drive the roads of hedgerow country is to experience a unique feeling of confinement quite different from the openness of barbed wire or unenclosed landscapes. In recent decades, hedgerows have been disappearing as landholdings have been consolidated and grown larger. The removal of hedgerows means not only the loss of a defining feature of the rural landscape but also a decline in habitat for many rare plants, mammals, and birds. In response, the U.K. government passed regulations in 1997 to protect hedgerows in England and Wales; these regulations appear to have slowed their removal.