MOBILITY

9.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Specify the ways in which mobilities of various sorts—of individuals as well as things and ideas—are important for development.

The movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place has rarely been symmetrical. Instead, some places are net exporters of people, goods, and ideas, while others import them. This has led to the enrichment of some places at the expense or the impoverishment of others. In this section, we consider aspects of how the mobility of people, goods, and ideas has shifted over time and from place to place, and how this affects people’s lives. We start by considering the importance of transportation and transportation-related infrastructure.

TRANSPORTATION AND DEVELOPMENT

Development, industrialization, and urbanization are profoundly connected. Development as we know it—both of the narrow economic sort as well as the broader attainment of basic needs and loftier human aspirations—could not have occurred without industrialization (i.e., the shift from primary to secondary sector activities) or the existence of cities (see Chapter 10). And, it is the movement of goods, people, and ideas from one place to another—transportation, in other words—that provides perhaps the most important element linking development, industrialization, and urbanization.

The Industrial Revolution saw a radical transformation in economic activities and processes. The Industrial Revolution began in England in the early 1700s. Machines, new power sources, and novel chemical processes replaced human hands in the making of products, initially in the cotton textile industry. In addition, many aspects of how people lived their lives in places were altered, including concepts of time, money, work, home, and gender roles.

Industrial Revolution

Beginning in England in the early 1700s, the Industrial Revolution saw the rapid transformation of the economy through the introduction of machines, new power sources, and novel chemical processes. These replaced human hands in the making of products, initially in the cotton textile industry.

The Industrial Revolution both encouraged and was furthered by the development of new forms of transportation. Traditional wooden sailing ships gave way to steel vessels driven by steam engines, and later railroads became more prevalent. The need to move raw materials and finished products from one place to another cheaply and quickly was the main stimulus that led to these transportation breakthroughs. Without them, the impact of the Industrial Revolution would have been minimized.

Once in place, the railroads and other innovative modes of transport associated with the Industrial Revolution fostered additional cultural diffusion. Ideas and, in fact, the Industrial Revolution itself spread more rapidly and easily because of this efficient transportation network.

Great Britain maintained a virtual monopoly on the Industrial Revolution well into the 1800s. Indeed, the British government actively tried to prevent other countries from acquiring the various inventions and innovations that distinguished the Industrial Revolution. After all, they gave Britain an enormous economic advantage and contributed greatly to the growth and strength of the British Empire. Nevertheless, this technology finally spread beyond the bounds of the British Isles, with continental Europe feeling the impact first. In the last half of the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution took firm root in the coalfields of Belgium, Germany, and other nations of northwestern and central Europe. The growth of railroads in Europe provides a good index of the spread of the Industrial Revolution there. The United States began rapid adoption of this new technology around 1850, followed half a century later by Japan, the first major non-Western nation to undergo full industrialization. In the first third of the twentieth century, industry and modern transport spilled over into Russia and Ukraine.

381

TRANSPORTATION AND THE COLONIAL LEGACY

As you have already seen in previous chapters, Europe’s colonization of large parts of the world from the fifteenth century through the early decades of the twentieth century has shaped much of today’s cultural geographies. That colonization was, in great measure, what allowed Europe to become wealthy and industrialized—developed—and also led to the progressive impoverishment and underdevelopment of the colonized areas.

The physical transportation of raw materials from the site of their extraction from the Earth, to places where they were processed into manufactured goods, was an essential aspect of industrialization. Before the advent of the steam engine in the late 1700s, for instance, the running water of streams and rivers drove the mechanical textile looms of northwestern England. However, once the steam engine came into use, textile factories were no longer geographically tied to locations with running water. They could be moved to cities where labor was cheaper and where transportation of their finished product to market—in ships and locomotives also powered by steam—was more centralized and efficient.

Thanks then to the steam engine and other transportation innovations, colonizer and colonized became drawn together in a geographically ever-wider and increasingly complex orbit. Raw materials such as cotton could be brought into England’s mill towns from as far away as India, to be spun, woven into fabric, dyed, and made into clothing. These finished goods were then re-exported to the colonies, to be sold at far higher prices than the original raw cotton had commanded.

All these activities involved transportation from one point to another, with many stops along the journey from raw material to final consumer. Transportation technologies and infrastructure (such as roads, railways, and ports) played a central role in the relationship between colonizer and colonized. Thus, it should not come as a surprise that struggles for independence were often waged on and around the means of transportation. In many colonial places, nationalization—the government takeover of the transportation infrastructure and fuel sources from private foreign ownership—was a crucial element. For example, Japan nationalized its railways in 1906, Mexico nationalized its petroleum industry in 1938, and Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956. Airlines, banks, and a wide variety of natural resources have also been subject to nationalization as a part of decolonization and independence movements.

nationalization

Government takeover of the transportation infrastructure and fuel sources from private foreign ownership, occurring in many previously colonized nations in the twentieth century.

Today, many formerly colonized countries have inherited the transportation infrastructure that was built during the colonial era. Because colonies were seen primarily as sources of raw materials, the primary focus of colonial-era infrastructure was moving the products extracted from the Earth— lumber, ores, minerals, and agricultural products—to ports and transporting them to factories in the cities of England, France, Germany, Belgium, Spain, and other colonial power centers, to be processed into finished goods. Latin America and Africa, in particular, have transportation infrastructures oriented toward the coasts and port cities. They do not, however, necessarily move people and goods about efficiently within the country.

Countries formerly colonized by the same European power are also not likely to be connected to each other. Long-distance air travel to African nations tends to make at least one stop in a European capital city en route, rather than flying direct. And, you may find it cheaper and even quicker to fly from one African city to a European capital first in order to get to a second African city, rather than flying directly within Africa. In other words, today even modern transportation infrastructure such as airports and flight routes may still be oriented toward transporting people to and from former colonial powers than within formerly colonized regions.

This is not to say that precolonial societies did not develop transportation networks and infrastructure: indeed, many did. For instance, the roadways of the Incan and Mayan societies in the Americas were noted for their complexity and high quality. The sixteenth-century Spanish conquerors of Peru observed the Incan road system to be better than the Roman roads at the time (Figure 9.15). Other remarkable roadways detailed in Highways, Byways, and Road Systems in the Pre-Modern World (see Ten Recommended Books on Development Geography) include those built by imperial China, in the indigenous U.S. Southwest, and trans-regional roadways across the Sahara Desert and the Silk Road through Asia. The major difference between precolonial and colonial-era transportation infrastructure was their orientation. Precolonial transportation routes focused inward, on moving people and goods across interiors and connecting places to each other; whereas colonial-era infrastructure for the most part was concerned with getting people and goods to sea and river ports as expediently as possible.

382

Major regional differences exist in the relative importance of the various modes of transport. In Russia and Ukraine, for example, highways are not very important to industrial development; instead, railroads—and, to a lesser extent, waterways—carry much of the transport load. Indeed, Russia still lacks a paved transcontinental highway. In the United States, by contrast, highways reign supreme, while the railroad system has declined in importance. Western European nations have a greater balance among rail, highway, and waterway transport.

AUSTRALIA’S COLONIAL RAILWAY WOES

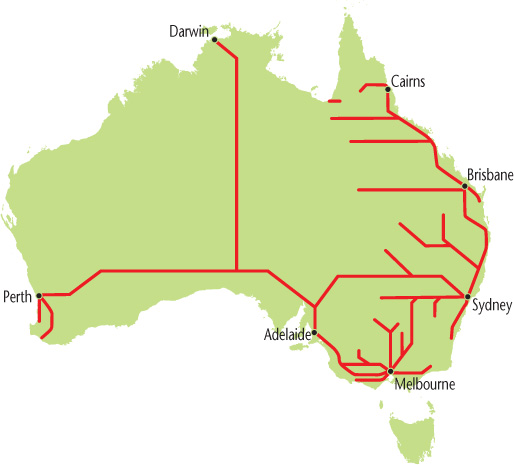

Even some countries that we would today consider to be “developed,” for instance, Australia, Canada, and Russia, developed rail systems and to a lesser extent roads that are primarily focused on moving raw materials to port and then on to European colonial powers. Figure 9.16 shows a map of the present-day Australian passenger rail system. Notice how the geographic focus of the routes is on the coastal areas, and that interior and transcontinental railways are few and far between.

Australia is coping with an additional colonial transportation legacy as well. The gauges (or widths) of railway tracks differ from state to state. Before the unified nation of Australia came into being in 1901, the continent consisted of six British colonies. Each developed its own railway system and, for a variety of personal and political reasons, chose different railway gauges. In 1848 the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London, Earl Grey (yes, the man associated with the tea that bears his name), advised the colonial governors to adopt a uniform railway gauge, the English Standard Gauge. Three of the colonies did so, while the others later adopted different gauges or a mixture of gauges.

383

Before unification, this system of differing gauges was not foreseen to be a problem because the colonial governors could not envision the need to connect their railways across the continent to one another. Rather, their focus was moving people and raw materials to the port cities and back and forth from Europe. Transcontinental freight or passenger traffic had to transfer lines as it crossed from one colony to another. Thus, the Australian railway network became a mixture of narrow, standard, and broad gauge tracks. Significant personnel and resources had to be devoted to so-called break-of-gauge activities in places where routes of different gauges became connected to one another. Several initiatives to convert to a standard railway gauge nationwide have been undertaken, but the work is slow, politically complicated, and expensive (Figure 9.17).

TRANSPORTATION HAVES AND HAVE-NOTS

As the Australian railroad gauge mismatch problem illustrates, modernizing transportation infrastructure can be a costly and difficult undertaking. Yet, having a modern transportation infrastructure in place is vital to a place’s ability to develop. For example, the port of San Francisco declined in importance relative to the port of Oakland just across the bay for this very reason. The local authorities were unwilling or unable to undertake the difficulties and expense of modernizing San Francisco’s port facilities to accommodate containerized shipping, whereas Oakland’s decision-makers took the plunge and modernized that port’s infrastructure (see Chapter 10).

384

Because of the colonial legacy, many of the world’s underdeveloped places have an inadequate transportation infrastructure. Old and dilapidated, failing to connect places to one another in an efficient fashion, mismatched, and often running on outdated technologies, these ports, roadways, and rail systems prevent a place from becoming developed. Much of Africa, Latin America, and former communist countries in Europe are facing this very predicament. Rightly or wrongly, their decision makers have determined that it is simply too expensive an undertaking to demolish existing facilities and build new, modern ones.

It is typically the poor that have the least access to everything related to development: income, health care, clean water and adequate food, housing, and so on. Where access to transportation infrastructure and mobility are concerned, this axiom generally holds true. For example, in Africa it is a fact that 90 percent of the continent’s land area and 80 percent of the population are 100 kilometers (62.1 miles) or more away from the sea coast or a navigable river. Given Africa’s colonial legacy of an extraction-oriented transportation infrastructure, this means that the majority of Africans do not have easy access to the infrastructure of mobility. As we have seen already, this makes moving about from place to place within the continent difficult and costly, and inhibits the sort of regional cooperation and integration that would allow African nations to work together to establish a stronger global economic presence. In other words, Africa’s colonial mobility legacy impedes the region’s development potential, making it all that much more difficult for an already poor place to progress.

Yet, we have also seen that places which are today thought of as developed—Russia, Canada, the United States, and Australia, in particular—have similarly extraction-focused transportation infrastructures. This is true because these countries (or regions within them) were themselves former colonies. At least in the United States, a persistent unwillingness to modernize the nation’s transportation infrastructure has and will continue to hurt the country economically. On the other hand, formerly underdeveloped areas that have emphasized the modernization and expansion of their transportation infrastructure, including many East Asian places, have become global hubs of economic mobility for this very reason.

We can also drill down deeper into the structure of mobility haves and have-nots within individual countries or cities.

Singapore’s Transportation Infrastructure Reboot Some formerly underdeveloped places have prioritized building a state-of-the-art transportation infrastructure. Many Asian nations fall into this category. Fifty years ago, for example, Singapore was an overcrowded, housing- and transportation-poor city-state situated at the southern the tip of the Malay Peninsula. Since the 1970s, the Singaporean government has prioritized transportation infrastructure expansion and modernization as a development strategy, to position Singapore as a regional Asian as well as global hub of economic exchange. Singapore expanded and modernized its deep-water port facilities. Today, one-fifth of the entire world’s container traffic and half of global crude oil shipments pass through the port of Singapore. Singapore’s airport facilities were moved from a residential area to reclaimed land away from the urban population. The new Changai Airport was expanded with the addition of terminals and runways, and is today an ultra-modern facility handling, on average, over a million passengers per week. Finally, Singapore’s Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) rail system, built in 1987, is a model of cleanliness, safety, and efficiency (Figure 9.18). The MRT claims to transport 2.5 million people per day around a city-state of roughly 5 million inhabitants. That’s half of the entire population moving about the city on mass transit.

385

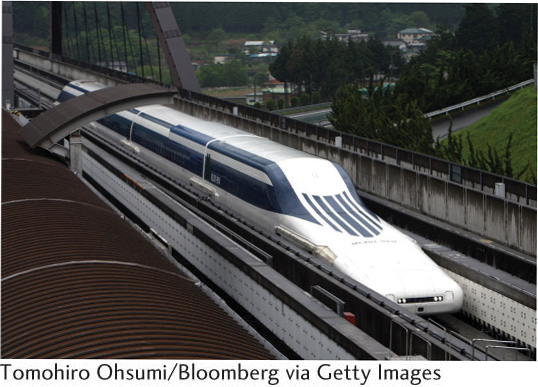

The investment has clearly paid off, though Singapore’s small size arguably makes such undertakings easier. In addition, Singapore’s government is criticized for being highly restrictive with respect to the civil liberties allowed their population: when a course of national investment is set, there is not much room for meaningful protest. The Chinese government is making similar investments in transportation infrastructure, on a much larger scale. Japan’s transportation infrastructure leads the world in high-tech innovation (Figure 9.19). South Korea as well is rapidly building a modern national transportation infrastructure. East Asia is “on track,” literally and figuratively speaking, to lead the world in transportation.

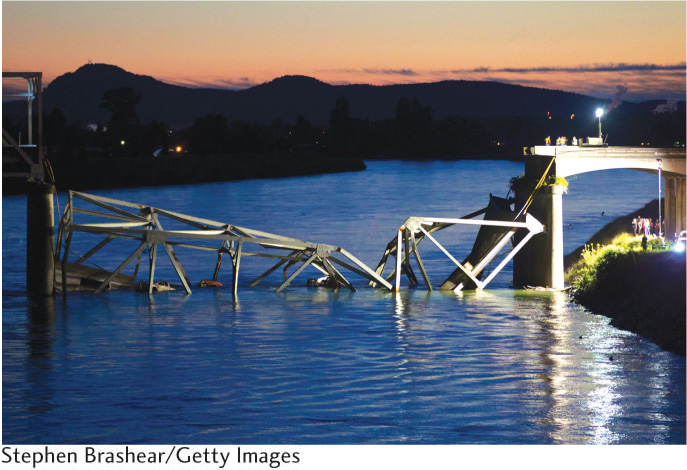

The United States: A Transportation Infrastructure Left Behind The United States provides an interesting example of a wealthy country whose aging transportation infrastructure is fast becoming a serious deterrent to the well-being of its citizens and a drag on economic growth. Think about recent “infrastructure incidents” in your local news: a collapsed bridge, airport delays arising from congestion, railway accidents due to damaged track or misrouted signals, or unsafe roadways closed to traffic (Figure 9.20). Why does the United States have so many problems with its transportation infrastructure?

386

As in many developing regions, the transportation infrastructure of the United States is generally old, outdated, and not adequately maintained (Figure 9.21). Most of the country’s railways, airports, seaports, bridges, and roadways were built decades, if not centuries, ago. The American Society of Civil Engineers publishes a Report Card for America’s Infrastructure. The 2013 report awarded an overall grade of D+ to the transportation infrastructure of the United States, estimating that some $3.6 trillion would need to be invested by the year 2020 to update it.

The World Economic Forum ranked America’s infrastructure 23rd worldwide, between Spain and Chile. Compared to northern Europe, the infrastructure for U.S. roads, railways, ports, and air transport is ranked “mediocre.” Traffic congestion, delays, and fatalities are significantly higher when compared to western Europe. By comparison to those in Europe, U.S. railways are slow and delays common. When it comes to air travel, a 1950s-era ground-tracking system forces flights to take inefficient routes to maintain contact with controllers, airports are overbooked, and cumbersome security measures cause passenger delays. The United States’ inland waterways and rivers, what the American Society of Civil Engineers calls “the hidden backbone of our freight network … inland marine highways,” received a grade of “D-,” which puts it on the line between poor and failing. Aging, unrepaired, and inadequate facilities cause an average of 52 service interruptions per day throughout this system.

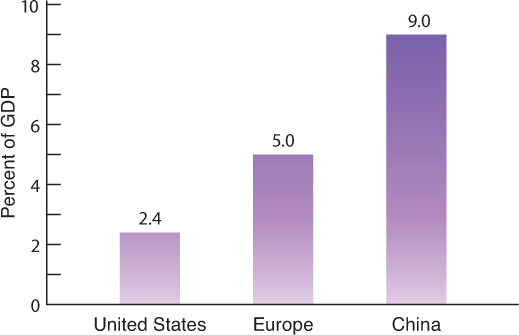

The deplorable state of the U.S. transportation infrastructure poses economic costs and real dangers to its users. The United States is today the world’s largest economy, but as Figure 9.22 shows, it spends far less as a percentage of GDP than other nations on infrastructure. This stands in direct contrast to a sustained history of large-scale transportation infrastructure construction in the United States, with the nation’s canal system constructed in the late 1700s, the transcontinental railway linking the East and West coasts created in the late 1800s, and the interstate highways built in the mid-1900s. What happened?

For one thing, Americans have insisted on low automobile and fuel taxes, yet in most countries these are a principal source of funding for building and maintaining roadways. Poor regional planning and political squabbling often lead to reluctance to fund construction and repairs. Budget crises at all levels—federal, state, and local—mean less public investment in transportation infrastructure, particularly in a deficit-averse environment. And, solutions that would privatize these costs, such as tolls, taxes, and fees levied on users, are unpopular. Only one thing is clear: the political gridlock preventing the prioritization of investment to repair and improve the U.S. transportation infrastructure is resulting in literal gridlock on the nation’s roads, railways, waterways, and airports.

387

Nicaragua’s Disembedded Elite Often it is the case that the elite residents of a place—whether the place in question is a city, a country, or a world region—have access to different and better (safer, quicker, more comfortable) transportation options than the less-well-off residents. This discrepancy is an example of how development geographies, in general, tend to be uneven, with the benefits accruing disproportionately to those who are already relatively well-off. Uneven development has spatial implications as well, with some places becoming progressively better-connected, wealthier, and more modern while others grow isolated, impoverished, and dilapidated.

If we consider the scale of most cities, the way that uneven development typically plays out is in the creation of enclaves or areas of relative wealth that exist side by side with areas of relative poverty. You might recall driving through a city where luxurious perhaps gated communities are located right next to impoverished ghettos or barrios. (See also Chapter 5.) In this case, spatial differences in development are very clear on the ground. Travel through such cities is seldom a straightforward exercise of moving from Point A to Point B, because roadways frequently bypass the poorer neighborhoods, while walls and fences make it impossible to transit freely through wealthier ones. As we will discuss in Chapter 10, this compromises the notion of public space, which so many have regarded as central to the exercise of democracy.

Research from Managua, Nicaragua, demonstrates how uneven development in some metropolises has become verticalized. Dennis Rodgers found that “rather than fragmenting into an archipelago of self-sustaining and isolated islands of wealth within a wider sea of poverty, urban space has undergone a process whereby a whole layer of the metropolis has been disconnected from the general fabric of the city.” Wealthy Managuans attempt to escape from rising crime rates by going up, rather than further out into the suburbs. Managua’s urban elites inhabit what Rodgers calls a “fortified network,” moving back and forth from high-rise apartments, office towers, and shopping and leisure spaces located above the poverty, insecurity, and pollution found in the street-level areas of the city. Roadways connecting elite urban spaces to each other were modernized so that elite car traffic could move at higher speeds across urban space. Roundabouts were constructed to reduce carjackings at intersections. Use of these roads presupposes ownership of a private vehicle and the ability to pay tolls. Pedestrians face significant dangers simply trying to cross multilane high-speed roadways: Rodgers reports that pedestrian fatalities constitute fully 40 percent of all traffic fatalities in Managua.

The next time you move through a large city, look around and see if you can find evidence of the verticalization of privilege. More and more cities around the globe look like Managua, where the urban elites have literally detached their lives from the social and spatial fabric of the city, hovering above it. Indeed, globalization in many areas—economic, technological, and even of celebrity—has reshaped places and their relationships to other places in ways that bring into question some of the fundamental assumptions of development.

388

Paraíso

![]() Paraíso

Paraíso

Three Mexican immigrants who work as window washers on Chicago’s downtown high-rise buildings are profiled in this video. The process of window washing is depicted, and the men speculate about the dangers—but also the beauty and craft—of the work they do. In addition, the men discuss more abstract notions: death, heaven, and the future that awaits them. Their conversations also bring up comparisons to the lives they might have lived had they stayed in Mexico. A great deal of nuance characterizes this video, and the three men’s understandings of central contrasts— between danger and beauty, poverty and wealth, heaven and earth—are not what you might expect.

Thinking Geographically:

One of the topics covered in this chapter’s Mobility section is the verticalization of privilege. How does this look in Chicago? In what specific ways do these men see and experience the verticalization of privilege from their vantage point as window washers?

Window washing is a dangerous occupation. How do these three men rationalize that danger? What do they view as the positive aspects of their job?

The three men talk a lot about wealth and poverty. Give some examples from the video of their understandings of wealth and poverty. Does anything strike you as unexpected?