GLOBALIZATION

9.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify how formerly poor places are today significant agents of development.

As we have already seen in this chapter, development today looks a lot different than it did right after World War II. In some very important ways, economic, technological, cultural, and even media-related transformations have brought different actors and sites into prominence. These transformations have fundamentally reoriented the landscape of global development geographies.

POSTDEVELOPMENT AND THE RISE OF THE GLOBAL SOUTH

Were today’s less developed places always poor, isolated, and largely engaged in primary sector activities? Not necessarily. As you have learned already, and will see again in the next chapter on urban geographies, many civilizations now considered “underdeveloped” formerly were hubs of economic activity, technological innovation, cultural diversity, and political dominance.

Consider the arc of Islamic influence, stretching from Rabat in northern Africa to Manila in Southeast Asia. As former university president William Frawley describes, “There is a fifteen-century-old line of faith and business that runs straight from Morocco to the Philippines and that has drawn Muslims and workers of need to countries of religion and economic prosperity.” This 7,600 mile (12,300 kilometer) sweep of Islamic influence constituted a vital corridor of economic, cultural, and political activity: an arc of development. It arose in a world where Europe had languished for centuries in the Dark Ages, and the so-called New World was populated by indigenous societies that were themselves centers of innovation and prosperity (see also Chapter 10).

The stark division between “developed” and “underdeveloped” places discussed earlier in the Region section has itself been largely redrawn. In reality, very few of the world’s places are impoverished, isolated, and predominantly agricultural anymore. Individual countries, like China, or entire regions, for instance, Sub-Saharan Africa or Southeast Asia, that did fit this profile as recently as 30 years ago have witnessed the transformation of their economic, political, technological, and cultural systems. Even within countries that may still be less developed as a whole, there are pockets of accelerated urbanization, innovation, and connection to global networks that make these locales look, feel, and act wealthy, contemporary, and plugged-in (Figure 9.23).

389

By the same token, places that several decades ago unquestionably occupied the ranks of the wealthy, connected, and modern—in other words, developed countries and regions—have slipped. Earlier, we discussed the United States’ crumbling transportation infrastructure and noted the high toll placed on economic productivity by this situation. Europe, too, has seen its seemingly secure First World status called into question by debt, financial crisis, an aging workforce, fears of terrorism, conflicts over immigration, and racist violence. In addition, places within these countries and regions, once centers of economic, technological, political, and cultural dynamism, have fallen on hard times.

The city of Detroit is a perfect example. Once a world leader in the auto industry and the United States’ fourth largest city, Detroit was home to secure jobs and seen as a cultural embodiment of quintessentially Midwestern American values and lifestyle. In 2013 Detroit declared bankruptcy, the largest U.S. city ever to do so. It has lost over half of its population since its heyday in 1950, and with it the tax base needed to pay for city services and maintenance. Financial mismanagement and the burden of health care and pensions for city workers have further impoverished Detroit. In many ways, Detroit’s landscape today is reminiscent of a Third World place (Figure 9.24).

Some scholars see these changes as evidence of postdevelopment: the idea that “development” was simply a way to categorize most of the world as needing the assistance of a few, wealthy nations. However, postdevelopment scholars argue, development as we knew it—in the form of monetary aid, investments, expertise, and projects—was seldom successful. Instead, development in reality constituted a modern form of imperialism, whereby wealthy nations ruled poor nations by controlling their economic, political, and cultural systems. The age of development, they argue, is over.

postdevelopment

A theoretical approach that is critical of standard development practices, asserting that traditional development efforts do not work because they are ultimately about controlling, not empowering, poor nations and people.

imperialism

A relationship whereby wealthy nations dominate poor ones by controlling their economic, political, and cultural systems.

390

Whether or not one agrees with this statement, it is clear that places formerly dismissed as underdeveloped have emerged as major players in a global world. There are several countries that are particularly important in what is commonly called the Global South: a term that has largely replaced Third World when referring to the countries of Latin America, Africa, and most of Asia. The term also represents an attempt to move beyond the negative connotations of “Third World,” recognizing that much of the world’s growth—economic, population, and urban—is happening in these countries, and that powerful contributions and alliances are emerging among them without the involvement of traditionally wealthy nations.

Global south

A term that has largely replaced “Third World” when referring to regions of Latin America, Africa, and most of Asia, in recognition that much of the world’s dynamism, growth, and power resides in these places.

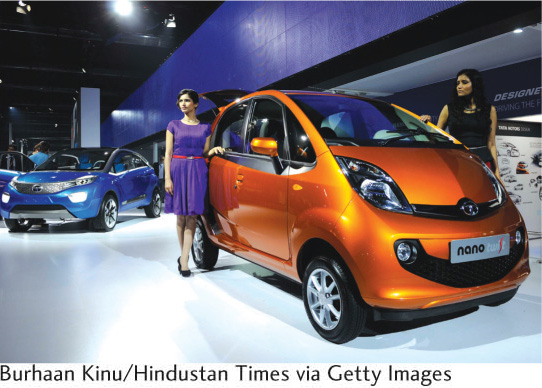

South-South cooperation is a major dimension of the dynamism occurring within the Global South. Several countries traditionally not part of the developed nations—Brazil, China, India, South Africa, Venezuela, Malaysia, and Indonesia among them—have large populations and growing economies. In many respects, they are the new centers for technical and economic development vis-à-vis their poorer neighbors. These countries are emerging as major global lenders, investors, researchers, educators, and employers (Figure 9.25). A report by the World Bank finds that South-South trade, for instance, has grown on average by 13 percent every year since 1995. They are also standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the world’s former political powerhouses, demanding a voice in issues like global climate change, energy use, and the world’s political organization.

south-south cooperation

Trade, technological innovation, and other forms of exchange and assistance that occur between the larger and wealthier nations of the Global South, and poorer nations.

TECHNOLOGY’S ROLE IN CLOSING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

Technology has long played a central role in economic development. Earlier in this chapter, we discussed Europe’s transformation from an agricultural to an industrial society, beginning in the eighteenth century. Recall that technological developments, particularly in powering machinery for manufacturing goods and transporting them, were the key to this transformation. Throughout the centuries that followed and today as well, revolutions in transportation and communications technologies continue to play a huge role in economic development. Small- to medium-sized enterprises in countries of the Global South are the catalysts for providing low-cost solutions to common problems there. Tata Motors, one of whose best-selling products is shown in Figure 9.25, is just one example. Other innovations are occurring in the fields of energy, environment, public health, education, and transportation.

India’s Aakash tablet computer, for instance, is priced around $35 U.S. with a government subsidy (it retails for around $60 U.S.). It is targeted for use in the educational sector, to expose Indian students to interactive online learning, testing, and computer programming. In another example, the One Laptop per Child initiative aims to facilitate children’s engagement with education by distributing low-cost, rugged, low-power, and connected laptops to students in 46 countries of the Global South, with the stated goal of “collaborative, joyful, and self-empowered learning.”

391

Mobile phones provide another field of South-South technological innovation and exchange. In 2012 the World Bank reported that three out of every four people on the planet have access to a mobile phone, and usage in the Global South has surpassed that in wealthy Northern countries. “Mobile phones are arguably the most ubiquitous modern technology: in some developing countries, more people have access to a mobile phone than to a bank account, electricity, or even clean water.” Mobile phones and applications (apps) are used by farmers, fishers, and traders to monitor weather conditions, track schools of fish, and follow market prices. Health care providers use mobile phones and apps to remotely diagnose ailments and to text patients medication reminders. Mobile phones are used by migrants to send money home, by citizens to monitor elections, and by workers to apply for jobs.

All these projects attempt to close the digital divide. The digital divide is the rift between those who benefit from easy access to the Internet and, more importantly, the vast storehouse of knowledge available online; and those who do not have easy access. The digital divide is a contemporary aspect of the longstanding gap between development’s haves and have-nots. Those who do not have easy access to the Internet are disadvantaged to the extent that they cannot readily participate in today’s globally connected world. Though Internet access is growing rapidly, 65 percent of the world’s inhabitants do not use the Internet (Figure 9.26). Even within wealthy countries, some segments of the population—the elderly, disabled people, and the poor—are far less likely to go online than are the young, healthy, and wealthy.

digital divide

The rift between those who benefit from easy access to the Internet and, more importantly, the vast storehouse of knowledge available online; and those who do not have easy access.

Part of the problem may be that the creators of the Internet and its content represent a narrow sector of the world’s population. According to Chris Csikszentmihályi, director of the MIT Center for Future Civic Media, “What you end up with is an Internet that assumes a particular kind of user, one that resembles the authors. So in a sense, almost everyone who uses the Internet has to sort of pass as a white, 20-something, urban-dwelling kind of person.” Consider, for instance, that since 2000 the Middle East has been the most active world region for growth in online use. Yet, less than 1 percent of Internet content is in Arabic. It is interesting to think about the ways that the growing Global South presence online might significantly reshape the Internet’s content and delivery.

392

GENDER, GLOBALIZATION, AND DEVELOPMENT

The traditional development models formulated after World War II were gender-blind. They did not distinguish between women and men in their understanding of how development unfolds in a place. In other words, development was supposed to affect everyone equally. Beginning in the 1970s, development geographers and others demonstrated that development is, in fact, a highly uneven process with respect to gender. Feminists in wealthy Northern countries were at that time concerned that the labor market in the developed world had systematically left women behind. Women were underpaid, unemployed and underemployed, and marginalized into certain sectors of the economy, such as teaching and nursing. The situation, feminists speculated, was likely to be the same in countries that were just then undergoing the process of development.

Evidence shows that women in the developing as well as the developed world earn less than their male counterparts, have fewer employment choices, and are far more likely to lose their jobs during economic downturns. In some societies in the developing world, there are cultural prohibitions against women working for wages outside of the home. These women are entirely economically dependent on their fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons for economic support. Research conducted in many areas of the developing world has demonstrated that men are more likely to spend their wages on alcohol and leisure activities, whereas women tend to use money for food, education, and health care (see also Subject to Debate).

Women’s economic vulnerability often translates into vulnerabilities in the other key arenas of development: among them, health, housing, safety, and education. The logical solution, according to this understanding, is to more fully include women in the development process, particularly in paid employment outside of the home. Women’s inclusion in the labor market would reduce their economic dependence on men; in addition, it would raise overall economic productivity. Figure 9.27 shows how the GDPs of several countries would rise if women were incorporated in the labor force at the same levels as men in those countries. Yet, such a solution overlooks several important factors.

First, many women are already involved in the development process, even if they do not participate in paid employment outside of the home. All of the labor performed by women in the home for free, including child care, meal preparation, in-home health care, and cleaning, subsidizes the world economy. This is true everywhere, not just in the Global South. Says New Zealand economist Marilyn Waring, “Unpaid work makes all the rest of work possible. The market wouldn’t survive if it wasn’t able to survive on the backbone of unpaid work.” Waring calculates unpaid labor, the vast majority of it performed by women, to be the largest sector of any national economy. If this so-called nonmarket household production was incorporated into the economic output of the United States, for instance, it would raise the national GDP by 26 percent.

Second, women—even those who are actively participating in paid employment outside of the home—face systematic barriers that men do not. For instance, women often confront discrimination, harassment, and violence in the labor market and specific workplaces, but also in other public spaces as well as inside their homes. Prevalent cultural associations of women with motherhood and the spaces of domesticity (see also Chapter 3) mean that women who work outside the home are seen as transgressing into male-dominated spaces. In order to force these women back into their homes and mothering roles, men—and other women as well as public policy and the media—subtly (and not so subtly) retaliate in a variety of ways.

393

394

Because such scenarios occur throughout the world, you are probably familiar with some of these retaliatory tactics. For instance, women moving through public spaces such as city streets and on public urban transit are subjected to catcalls, groping, and sexual assault. Working Indian women have been raped on public transit and in city spaces, reports of which have only recently become international news. Since the 1990s, hundreds of female factory workers in Northern Mexico have been murdered as they traveled to and from their jobs.

Women’s mobility is restricted in other ways as well. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, women are still legally forbidden to drive automobiles. Many societies expect women to dress in restrictive clothing that limits their mobility and comfort in the name of modesty. You might think of high-heeled shoes as an example of this tactic. Even the persistently lower pay for women the world over who hold the same jobs as men can be seen as a tactic to discourage women who work. In the United States, young college-graduate women working full time, on average, make 82 percent of what their male counterparts are paid; in South Korea and Japan, women earn less than 70 cents for every dollar earned by a man. In many ways, women are still second-class citizens, a reality that hinders progress in development by holding back fully one-half of humanity.

Subject To Debate: MICROFINANCE AND DEVELOPMENT

Subject To Debate

MICROFINANCE AND DEVELOPMENT

In the 1970s, an economics professor by the name of Mohammed Yunnus was troubled. On the one hand, he was teaching textbook economic theory; while on the other hand, he was surrounded by the poverty and hunger of so many inhabitants of his native Bangladesh. One thing that stood out to Professor Yunnas was the difficulty faced by poor people, particularly women, in securing credit. Banks didn’t want to lend to them because they had no assets or credit history. The loan sharks who did lend to women demanded exorbitant interest rates in return. Yunnus himself initially loaned a total of $27, which was enough to erase the debts of 42 individuals.

In 1983 Yunnus founded the Grameen (“Village”) Bank. The Grameen Bank lends only to those without assets or credit, and requires loan recipients to educate their children and establish savings. Most of the microloan recipients are women or groups of women, who—far from being credit risks—have very high loan repayment rates. The loans, which average $100, are used to establish small businesses and to lift families out of poverty. In 2006 Yunnus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize; at that time, over 7 million individuals had received loans through the Grameen Bank.

Why do microfinance efforts like the Grameen Bank focus on women? Research and experience have shown that poor women in the Global South by and large prioritize expenditures on family well-being, including health care, nutrition, and education. Poor men, on the other hand, often spend money on short-term pursuits that do not enhance family well-being, such as leisure activities and alcohol. In addition, women are far more likely than men to repay loans on time and in full and less likely to default.

Microfinance efforts throughout the developing world challenge the traditional focus of economic development, which emphasizes lending significant sums of money to organizations and governments to finance large-scale projects. Women are typically not well represented in the ranks of formal development organizations and national governments. In some ways, you might think of microfinance as a postdevelopment undertaking.

Continuing the Debate

Consider the debates surrounding microfinance, and ask yourself these questions:

•Do you believe that women are truly better credit risks than men? Why or why not?

•Microloans are for such small amounts of money—can they really make a difference?

•Are microfinance initiatives under way where you live?

CELEBRITIES AND DEVELOPMENT

Technology is not just good for solving logistical problems in poor areas, such as bringing electricity to remote villages or tracking the height and weight of children. In the development field, technology has also been used to create communities of concern and action that are truly global in scope. Many times, celebrity figures from the world of music, film, and sports are the faces of such communities. This is not a new development. In 1940, for instance, silent movie star Charlie Chaplin’s first talking film The Great Dictator condemned Hitler, Nazi Germany, and fascism. Film star Jane Fonda was a very vocal participant in the antiwar movement of the 1960s. Singer Johnny Cash performed at California’s Folsom State Prison, in part to protest conditions there in 1968.

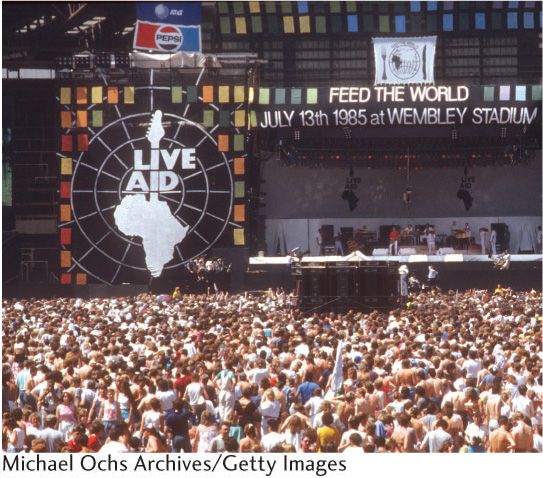

The Ethiopian famine of 1984, however, heralded the advent of contemporary high-profile celebrity-led development efforts televised worldwide. The 1985 Live Aid charity concert, assembled by the Boomtown Rats’ front man Bob Geldof, was the most visible of these early efforts (Figure 9.28). Geldof had been deeply affected by coverage of the famine, which claimed more than 1 million lives. Geldof assembled a superstar musical lineup, including Bono, Mick Jagger, Elton John, Madonna, Paul McCartney, and B. B. King, performing in one of two shows broadcast via satellite technology. Phil Collins actually performed in both events: first in London and then, after flying across the Atlantic to perform again with the reunited superband Led Zeppelin, in Philadelphia. Each performer had no more than 17 minutes on stage, and the performances were interspersed with film clips depicting the famine and calls by Geldof to donate money to the famine relief efforts.

MTV estimated that 1.4 billion of the world’s then 5 billion inhabitants watched, and that at one point 95 percent of the world’s television sets were tuned in to the concert. More than $200 million was raised. Keep in mind that this huge participation occurred in the mid-1980s, when cell phones, the Internet, and Twitter did not exist. Indeed, the 1981 birth of MTV—and the music video—can itself be seen as a technological innovation facilitating massive charity rallies such as Live Aid. Broadcasts like this one allowed virtual participation, leading to a widening of the concerned community away from just the face-to-face audience at live concerts. MTV thrived on the repeated playing of music video clips, and those shot at Live Aid were soon iconic, such as U2’s performance of “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” These performances resonated with the career development of this era’s pop musicians, which would become increasingly video-based rather than linked solely to live performances.

395

Since then, there have been any number of celebrities associated with causes in the Global South. Actors, musicians, and television personalities make up a large portion of such celebrity ranks: Angelina Jolie, Madonna, George Clooney, Oprah Winfrey, and Leonardo DiCaprio have all engaged in social justice charity work in Africa, for instance. To be sure, the wealth, mobility, and cultural visibility of celebrities can go a long way toward bringing worldwide attention to events that might otherwise remain under the digital radar. These individuals leverage their fame to raise millions of dollars for development-related causes, sometimes far more effectively than the traditional economic development agencies officially charged with funding development efforts in the Global South.

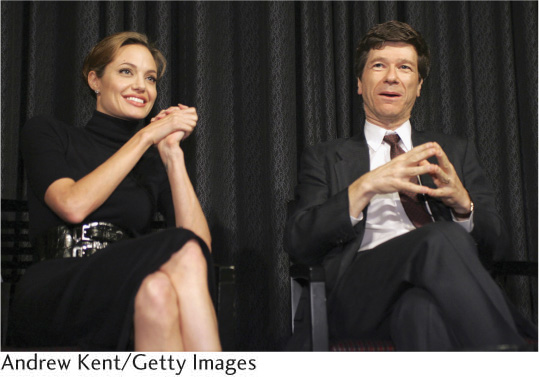

Nevertheless, there is also widespread criticism of celebrity development efforts. Most media celebrities are not trained economists, climate change scientists, medical doctors, educators, or social workers. In some ways, they are playing a role—that of development expert—they are not really qualified to play. A few celebrities acknowledge this and have teamed up with international development organizations or experts. Figure 9.29 depicts Angelina Jolie’s professional association with renowned development economist Jeffrey Sachs, for example. Others, however, seem oblivious to their limitations, as seen in the example of Madonna’s failed $3.8 million Malawian school project, apparently a victim of financial mismanagement.

Critics have noted that celebrity development efforts tend to portray the Global South and its residents as passive victims of calamity who are waiting for wealthy Westerners to rescue them. Writes Andrew M. Mwenda, “So some [celebrities] come to save orphans, others to defend human rights, feed the hungry, treat the sick, educate our children, protect the environment, end civil wars, negotiate aid and promote family planning, lest we overproduce ourselves. It is almost as if Africans cannot do anything by themselves and need a combination of Mother Teresa and Santa Claus to survive.” Critics of celebrity development figures suggest that their efforts are more about attempting to enhance the individual celebrity’s brand, rather than reflecting any true concern with living people and places.

In 2010 Twitter technology spawned the Digital Death campaign on December 1, World AIDS day. Music, sports, and entertainment personalities such as Usher, Swizz Beats, Kim Kardashian, Ryan Seacrest, Justin Timberlake, and Alicia Keys posed in caskets. They threatened to leave their collective 30 million Twitter followers “in the dark” until $1 million was raised. Videos narrating each celebrity’s “last tweet and testament” implored viewers to buy back their favorite star’s digital life; until then, there would be no Facebook or Twitter, no beats and no music (see Development Geography on the Internet for a link to the last tweets and testament videos of participating stars). Justin Timberlake, for instance, claims to have “sacrificed my digital life in order to give real life to millions of people who are affected by HIV and AIDS in Africa and India.” The Digital Death campaign raised $1 million within a week, but there is speculation that the stars kicked in cash of their own to reach the goal and buy back their digital lives. In all likelihood, celebrity development efforts are not entirely naïve and self-serving undertakings. In some ways, they underscore a longstanding and problematic relationship between the world’s haves and have-nots.

396

As we have seen, technological, cultural, and political transformations at the global scale will certainly continue to shape and reshape how development is practiced and who benefits.