CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

9.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Observe how development projects have shaped the landscapes around us.

It is difficult to look at any particular landscape and not see some evidence of economic development. Factories, shopping malls, housing developments, industrial agriculture, cities: all provide examples of landscapes that arise over the course of economic development. There is literally no place on Earth that has not been touched in some way by human activity.

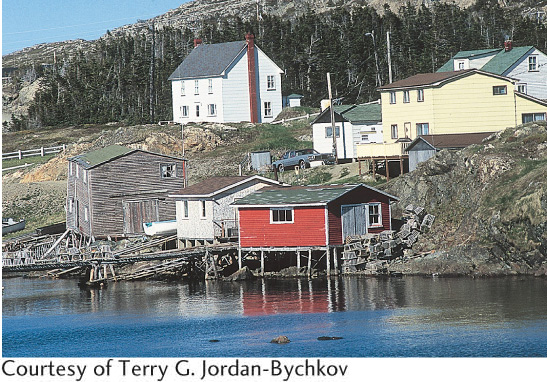

Primary industries produce perhaps the most drastic impacts. The resulting landscapes contain slag heaps, clear-cut commercial forests, strip-mining and open-pit mining scars, and forestlike clusters of oil derricks (Figure 9.33). The destruction of nature is less apparent in other types of primary industrial landscapes. The fishing villages of Portugal and Newfoundland continue to attract tourists even though the fisheries are depleted (Figure 9.34). In still other cases, efforts are made to restore the preindustrial landscape or to repurpose it into something more attractive. Examples include the establishment of artificial new grasslands in old strip-mining areas of the American Midwest, and the creation of recreational ponds in old mine pits along interstate highways.

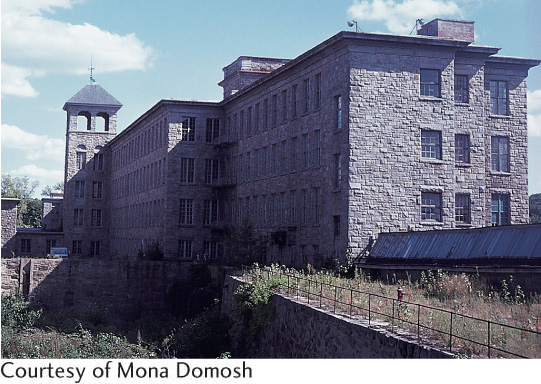

Among the most obvious features of the landscapes of secondary sector activities (manufacturing) are factory buildings. Early- to mid-nineteenth-century industrial landscapes are easy to identify, because the technologies that ran these factories were reliant on water power. Hence, the mill buildings that housed the machinery were designed in linear form to take full advantage of the turbines that were connected to waterwheels. Given this locational requirement, these mill complexes were most often built in rural areas. Entire communities, usually with housing for the workers, thus had to be constructed along with the mills. These mill towns dotted the landscape of England, Scotland, and New England, the site of the first industrial developments in the United States (Figure 9.35 and Mona’s Notebook). Later—as water power was supplanted by steam, coal, and then electric power—factories were located near urban areas, taking advantage of the housing supply already there and the proximity to a large consumer base. These industrial landscapes were often located at the edge of downtowns, lining the railroad routes into the city, and were surrounded by working-class housing. In the second half of the twentieth century—with the development of the interstate highway system and the trucking industry, as well as the switch to high-tech industries such as electronics—industrial landscapes took on a different form. Factories began to move to industrial parks at interstate exchanges, and their architecture began to resemble other types of mass-produced architecture (Figure 9.36).

403

Given the degree of deindustrialization in certain parts of the old core industrial regions, it is not surprising that many of these factory complexes, particularly those that date from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, are derelict or are being repurposed for housing or commercial uses. Others now house historical museums depicting past industrial technologies and ways of life. Lowell, Massachusetts, an early (mid-nineteenth-century) planned industrial town that produced textiles, is now the site of a national park. A good percentage of its factories, canals, and housing complexes have been preserved and can be toured by visitors. In Great Britain, many sites of industrial history are now preserved as museums (see World Heritage Site).

Service industries, too, produce a cultural landscape. Its visual content includes elements as diverse as high-rise bank buildings, fast-food restaurants, gasoline stations, strip malls, and the concrete and steel webs of highways and railroads. Some highway interchanges can best be described as a modern art form, but perhaps the aesthetic high point of the industrial landscape may be found in bridges, which are often graceful and beautiful structures. The massive investment in these transportation systems has even changed the way we view the landscape. As geographer Yi-Fu Tuan commented, “In the early decades of the twentieth century vehicles began to displace walking as the prevalent form of locomotion, and street scenes were perceived increasingly from the interior of automobiles moving staccato-fashion through regularly spaced traffic lights.” Yet, the ubiquity of such landscapes throughout the world has led to a sense of loss of the distinctiveness from one place to another. What geographers call placelessness—a disorienting sense of sameness in the cultural landscape—is on the rise (see Chapter 2).

placelessness

A disorienting sense of sameness in the cultural landscape.

404

Producer services related to financial activities, such as legal services, trade, insurance, and banking, traditionally were located in high-rise buildings in urban centers, but with suburbanization they have taken on a nonurban form. Many are now located in five- or six-story buildings, along the interstates surrounding cities, in what we’ve called high-tech corridors. Other producer service industries choose to maintain their downtown location for symbolic reasons. Some consumer services, particularly retailing, have created distinctive and, within the American context at least, socially important landscapes. Shopping malls are now dominant features of the North American suburb and often serve as catalysts for suburban land development, in effect creating entirely new landscapes, all geared toward consumption. As more and more of this activity moves online, it is interesting to contemplate what sorts of landscapes will be created.

Indeed, the quaternary sector landscapes of intellectual and informational activities—including the development of technology that allows the other sectors to conduct business in an online environment—are notoriously difficult to see. Yet, these landscapes do exist. Named after a place that founder Jeff Bezos thought to be “exotic and different,” Amazon.com began life as an online bookstore. Today, you may purchase just about anything you can think of from Amazon.com. Its headquarters are located in Seattle, Luxembourg, and Belgium. Nevertheless, its physical locations also include a vast global network of mammoth warehouses and fulfillment centers, and software development and customer service offices. Much of Amazon.com's business, however, is conducted in noncommercial locations such as households: with customers ordering online in their pajamas, for instance. It also occurs in nonplaces. Think, for example, of Amazon’s cloud computing services, or the books and video only available in digital format. The company is envisioning same-day delivery of orders via drone in some urban markets as early as 2015 (Figure 9.37). This reshaping of the quaternary sector cultural landscape echoes the vertical landscapes of privilege discussed previously.