Thinking Critically about Hard Evidence

Thinking Critically about Hard Evidence

Aristotle helps us out in classifying arguments by distinguishing two kinds:

| Artistic Proofs | Arguments the writer/speaker creates | Constructed arguments | Appeals to reason; common sense |

| Inartistic Proofs | Arguments the writer/speaker is given | Hard evidence | Facts, statistics, testimonies, witnesses, contracts, documents |

We can see these different kinds of logical appeals at work in a single paragraph from President Barack Obama’s 2014 State of the Union address. Typically in such speeches — nationally televised and closely reviewed — the president assesses the current condition of the United States and then lays out an agenda for the coming years, a laundry list of commitments and goals. One of those items mentioned about halfway through the 2014 address focuses on the admirable objective of improving the conditions of working women:

Today, women make up about half our workforce. But they still make 77 cents for every dollar a man earns. That is wrong, and in 2014, it’s an embarrassment. A woman deserves equal pay for equal work. She deserves to have a baby without sacrificing her job. A mother deserves a day off to care for a sick child or sick parent without running into hardship — and you know what, a father does, too. It’s time to do away with workplace policies that belong in a Mad Men episode. This year, let’s all come together — Congress, the White House, and businesses from Wall Street to Main Street — to give every woman the opportunity she deserves. Because I firmly believe when women succeed, America succeeds.

— Barack Obama, State of the Union address

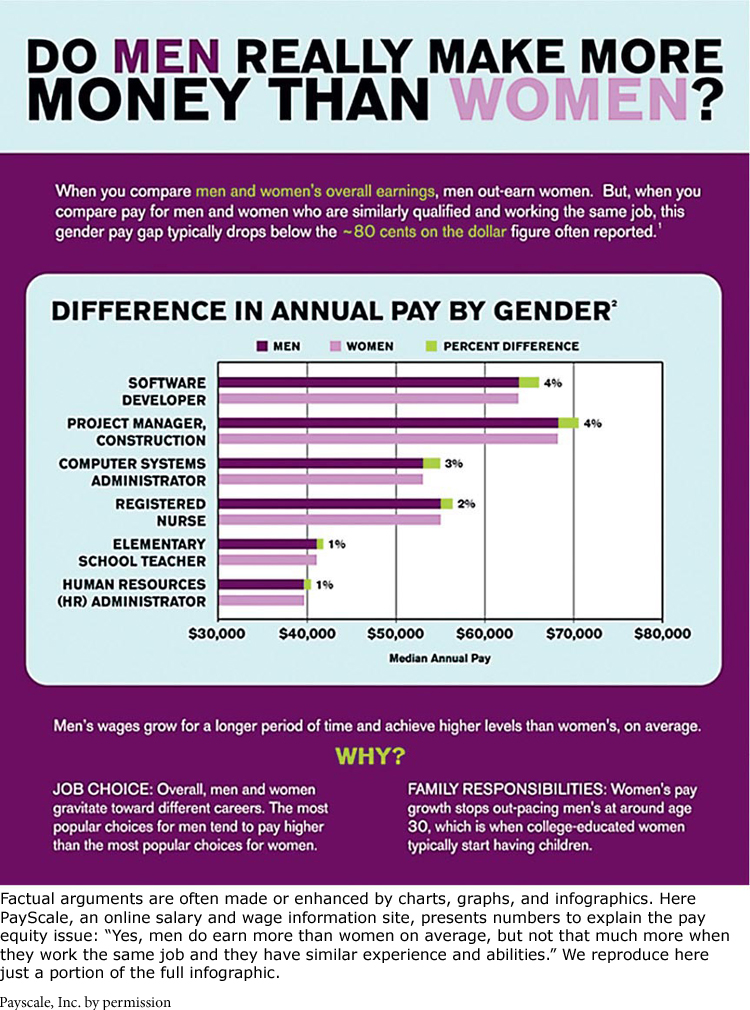

As you see, Obama opens the paragraph with an important “inartistic” proof, that ratio of just 77 cents to a dollar representing what women earn in the United States compared to men. Beginning with that fact, he then offers a series of reasonable “artistic” appeals phrased as applause lines: that is wrong; a woman deserves equal pay; a mother deserves a day off . . . a father does, too.” Obama then concludes the paragraph by stating the core principle behind all these claims, what we’ll later describe as the warrant in an argument (see Chapter 7): when women succeed, America succeeds.

Note, then, the importance of that single number the president puts forward. It is evidence that, despite decades of political commitment to pay equity and even federal laws banning gender discrimination in employment and compensation, much work remains to be done. Who can be satisfied with the status quo in the face of that damning number? But where did that statistic come from, and what if it is wrong?

Now, no one expects footnotes and documentation in a presidential address. The ethos of the office itself makes the public (at least some portion of it) willing to accept a president’s factual claims, if only because his remarks have surely been vetted by legions of staffers. Yet some statistics and claims assume a life of their own, repeated so often that most people — even presidents and their speechwriters — assume that they are true. Add the problem of “confirmation bias,” the tendency of most people to believe evidence that confirms their views of the world, and you have numbers that will not die.

We live, however, in an age of critics and fact-checkers. Writing for the Daily Beast, Christina Hoff Sommers, a former professor of philosophy and no fan of contemporary feminism, complains that the president is perpetuating an error: “What is wrong and embarrassing is the President of the United States reciting a massively discredited factoid.” And in case you won’t believe Sommers (and most feminists and those in the president’s camp wouldn’t), she directs skeptics to a more objective source, the Washington Post, which routinely fact-checks the State of the Union and other major addresses.

Like Sommers, that paper does raise questions about the 77/100 earnings ratio, and its detailed analysis of that number suggests just how complicated evidential claims can be. Here’s a shortened version of the Post’s statement, which you’ll note cites several government sources:

There is clearly a wage gap, but differences in the life choices of men and women — such as women tending to leave the workforce when they have children — make it difficult to make simple comparisons.

Obama is using a figure (annual wages, from the Census Bureau) that makes the disparity appear the greatest. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, for instance, shows that the gap is 19 cents when looking at weekly wages. The gap is even smaller when you look at hourly wages — it is 14 cents — but then not every wage earner is paid on an hourly basis, so that statistic excludes salaried workers. . . .

Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis surveyed economic literature and concluded that “research suggests that the actual gender wage gap (when female workers are compared with male workers who have similar characteristics) is much lower than the raw wage gap.” They cited one survey, prepared for the Labor Department, which concluded that when such differences are accounted for, much of the hourly wage gap dwindled, to about 5 cents on the dollar.

Is the entire paragraph of the president’s address discredited because his hard evidence seems overstated or oversimplified? Not if we accept the constructed arguments he makes on the general principle of fairness for offering women — and men — more support as laborers in the job force. But he might have been more convincing at this point in a very lengthy speech if someone in the White House had taken a moment to check the government’s own numbers, as the Washington Post did. This ongoing controversy over wage equity does, however, illustrate how closely logical arguments — whether artistic or inartistic — will be read and criticized. And so the connections between them matter.

RESPOND •

Discuss whether the following statements are examples of hard evidence or constructed arguments. Not all cases are clear-cut.

Drunk drivers are involved in more than 50 percent of traffic deaths.

DNA tests of skin found under the victim’s fingernails suggest that the defendant was responsible for the assault.

A psychologist testified that teenage violence could not be blamed on video games.

An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Air bags ought to be removed from vehicles because they can kill young children and small-framed adults.

Facts

Gathering factual information and transmitting it faithfully practically define what we mean by professional journalism and scholarship. We’ll even listen to people we don’t agree with if their evidence is really good. Below, a reviewer for the conservative National Review praises William Julius Wilson, a liberal sociologist, because of how well he presents his case:

In his eagerly awaited new book, Wilson argues that ghetto blacks are worse off than ever, victimized by a near-total loss of low-skill jobs in and around inner-city neighborhoods. In support of this thesis, he musters mountains of data, plus excerpts from some of the thousands of surveys and face-to-face interviews that he and his research team conducted among inner-city Chicagoans. It is a book that deserves a wide audience among thinking conservatives.

— John J. DiIulio Jr., “When Decency Disappears” (emphasis added)

When your facts are compelling, they may stand on their own in a low-stakes argument, supported by little more than saying where they come from. Consider the power of phrases such as “reported by the Wall Street Journal” or “according to FactCheck.org.” Such sources gain credibility if they have reported facts accurately and reliably over time. Using such credible sources in an argument can also reflect positively on you.

In scholarly arguments, which have higher expectations for accuracy, what counts is drawing sober conclusions from the evidence turned up through detailed research or empirical studies. The language of such material may seem dryly factual to you, even when the content is inherently interesting. But presenting new knowledge dispassionately is (ideally at least) the whole point of scholarly writing, marking a contrast between it and the kind of intellectual warfare that occurs in many media forums, especially news programs and blogs. Here for example is a portion of a lengthy opening paragraph in the “Discussion and Conclusions” section of a scholarly paper arguing that people who spend a great deal of time on Facebook often frame their lives by what they observe there:

The results of this research support the argument that using Facebook affects people’s perceptions of others. For those that have used Facebook longer, it is easier to remember positive messages and happy pictures posted on Facebook; these readily available examples give users an impression that others are happier. As expected in the first hypothesis, the results show that the longer people have used Facebook, the stronger was their belief that others were happier than themselves, and the less they agreed that life is fair. Furthermore, as predicted in the second hypothesis, this research found that the more “friends” people included on their Facebook whom they did not know personally, the stronger they believed that others had better lives than themselves. In other words, looking at happy pictures of others on Facebook gives people an impression that others are “always” happy and having good lives, as evident from these pictures of happy moments. In contrast to their own experiences of life events, which are not always positive, people are very likely to conclude that others have better lives than themselves and that life is not fair.

— Hui-Tzu Grace Chou, PhD, and Nicholas Edge, BS, “‘They Are Happier and Having Better Lives Than I Am’: The Impact of Using Facebook on Perceptions of Others’ Lives”

There are no fireworks in this conclusion, no slanted or hot language, no unfair or selective reporting of data, just a faithful attention to the facts and behaviors uncovered by the study. But one can easily imagine these facts being subsequently used to support overdramatized claims about the dangers of social networks. That’s often what happens to scholarly studies when they are read and interpreted in the popular media.

Of course, arguing with facts can involve challenging even the most reputable sources if they lead to unfair or selective reporting or if the stories are presented or “framed” unfairly.

In an ideal world, good information — no matter where it comes from — would always drive out bad. But you already know that we don’t live in an ideal world, so sometimes bad information gets repeated in an echo chamber that amplifies the errors.

Statistics

You’ve probably heard the old saying “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” and, to be sure, it is possible to lie with numbers, even those that are accurate, because numbers rarely speak for themselves. They need to be interpreted by writers — and writers almost always have agendas that shape the interpretations.

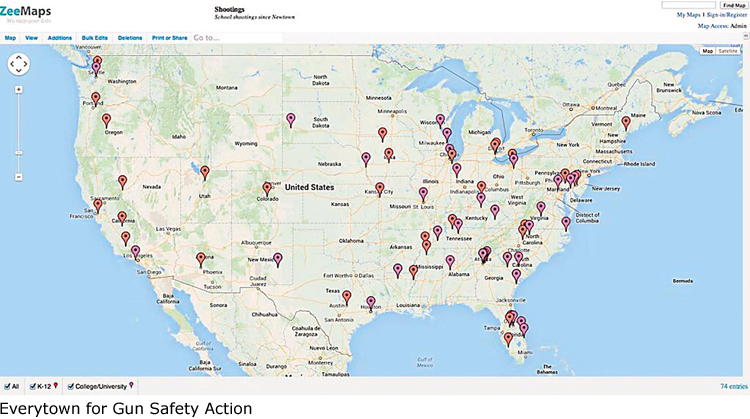

Of course, just because they are often misused doesn’t mean that statistics are meaningless, but it does suggest that you need to use them carefully and to remember that your careful reading of numbers is essential. Consider the attention-grabbing map below that went viral in June 2014. Created by Mark Gongloff of the Huffington Post in the wake of a school shooting in Oregon, it plotted the location of all seventy-four school shootings that had occurred in the United States since the Sandy Hook tragedy in December 2012, when twenty elementary school children and six adults were gunned down by a rifle-wielding killer. For the graphic, Gongloff drew on a list assembled by the group Everytown for Gun Safety, an organization formed by former New York City mayor and billionaire Michael Bloomberg to counter the influence of the National Rifle Association (NRA). Both the map and Everytown’s sobering list of shootings received wide attention in the media, given the startling number of incidents it recorded.

It didn’t take long before questions were raised about their accuracy. Were American elementary and secondary school children under such frequent assault as the map based on Everytown’s list suggested? Well, yes and no. Guns were going off on and around school campuses, but the firearms weren’t always aimed at children. The Washington Post, CNN, and other news outlets soon found themselves pulling back on their initial reporting, offering a more nuanced view of the controversial number. To do that, the Washington Post began by posing an important question:

What constitutes a school shooting?

That five-word question has no simple answer, a fact underscored by the backlash to an advocacy group’s recent list of school shootings. The list, maintained by Everytown, a group that backs policies to limit gun violence, was updated last week to reflect what it identified as the 74 school shootings since the massacre in Newtown, Conn., a massacre that sparked a national debate over gun control.

Multiple news outlets, including this one, reported on Everytown’s data, prompting a backlash over the broad methodology used. As we wrote in our original post, the group considered any instance of a firearm discharging on school property as a shooting — thus casting a broad net that includes homicides, suicides, accidental discharges and, in a handful of cases, shootings that had no relation to the schools themselves and occurred with no students apparently present.

— Niraj Chokshi, “Fight over School Shooting List Underscores Difficulty in Quantifying Gun Violence”

CNN followed the same path, re-evaluating its original reporting in light of criticism from groups not on the same page as Everytown for Gun Safety:

Without a doubt, that number is startling.

So . . . CNN took a closer look at the list, delving into the circumstances of each incident Everytown included. . . .

CNN determined that 15 of the incidents Everytown included were situations similar to the violence in Newtown or Oregon — a minor or adult actively shooting inside or near a school. That works out to about one such shooting every five weeks, a startling figure in its own right.

Some of the other incidents on Everytown’s list included personal arguments, accidents and alleged gang activities and drug deals.

— Ashley Fantz, Lindsey Knight, and Kevin Wang, “A Closer Look: How Many Newtown-like School Shootings since Sandy Hook?”

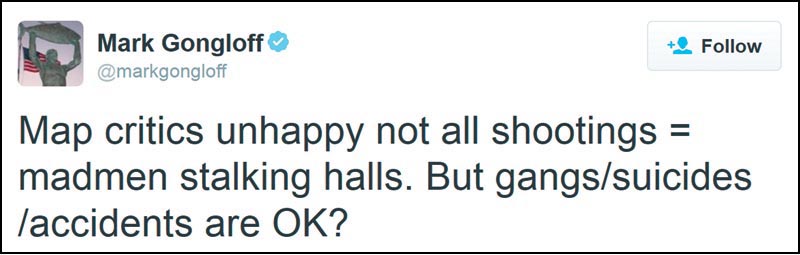

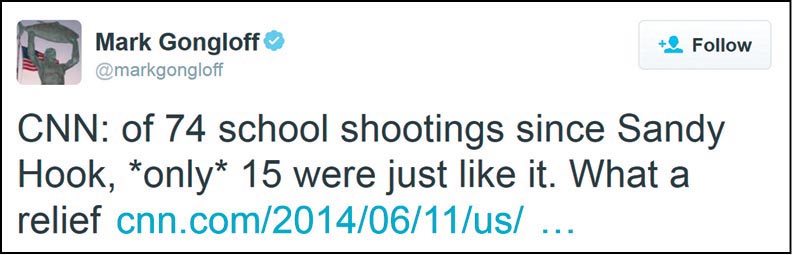

Other news organizations came up with their own revised numbers, but clearly the interpretation of a number can be as important as the statistic itself. And what were Mark Gongloff’s Twitter reactions to these reassessments? They made an argument as well:

One lesson, surely, is that when you rely on statistics in your arguments, make sure you understand where they come from, what they mean, and what their limitations might be. Check and double-check them or get help in doing so: you don’t want to be accused of using fictitious data based on questionable assumptions.

RESPOND •

Statistical evidence becomes useful only when interpreted fairly and reasonably. Go to the USA Today Web site and look for the daily graph, chart, or table called the “USA Today Snapshot.” Pick a snapshot, and use the information in it to support three different claims, at least two of which make very different points. Share your claims with classmates. (The point is not to learn to use data dishonestly but to see firsthand how the same statistics can serve a variety of arguments.)

Surveys and Polls

When they verify the popularity of an idea or a proposal, surveys and polls provide strong persuasive appeals because they come as close to expressing the will of the people as anything short of an election — the most decisive poll of all. However, surveys and polls can do much more than help politicians make decisions. They can be important elements in scientific research, documenting the complexities of human behavior. They can also provide persuasive reasons for action or intervention. When surveys show, for example, that most American sixth-graders can’t locate France or Wyoming on a map — not to mention Ukraine or Afghanistan — that’s an appeal for better instruction in geography. It always makes sense, however, to question poll numbers, especially when they support your own point of view. Ask who commissioned the poll, who is publishing its outcome, who was surveyed (and in what proportions), and what stakes these parties might have in its outcome.

Are we being too suspicious? No. In fact, this sort of scrutiny is exactly what you might anticipate from your readers whenever you use (or create) surveys to explore an issue. You should be confident that enough subjects have been surveyed to be accurate, that the people chosen for the study were representative of the selected population as a whole, and that they were chosen randomly — not selected because of what they are likely to say. In a splendid article on how women can make research-based choices during their pregnancy, economist Emily Oster explores, for example, whether an expectant mother might in fact be able to drink responsibly. She researches not only the results of the data, but also who was surveyed, and how their participation might have influenced the results:

It is possible to unearth research that points to light drinking as a problem, but this work is deeply flawed. One frequently cited study from the journal Pediatrics, published in 2001, interviewed women about their drinking while they were pregnant and then contacted them for a child behavior assessment when their children were about 6. The researchers found some evidence that lighter drinking had an impact on behavior and concluded that even one drink a day could cause behavior problems.

So what’s wrong with this finding?

In the study, 18% of the women who didn’t drink at all and 45% of the women who had one drink a day reported using cocaine during pregnancy. Presumably your first thought is, really? Cocaine? Perhaps the problem is that cocaine, not the occasional glass of Chardonnay, makes your child more likely to have behavior problems.

— Emily Oster, “Take Back Your Pregnancy”

Clearly, polls, surveys, and studies need to be examined critically. You can’t take even academic research at face value until you have explored its details.

The meaning of polls and surveys is also affected by the way that questions are posed. In the recent past, research revealed, for example, that polling about same-sex unions got differing responses according to how questions are worded. When people were asked whether gay and lesbian couples should be eligible for the same inheritance and partner health benefits that heterosexual couples receive, a majority of those polled said yes — unless the word marriage appeared in the question; then the responses are primarily negative. If anything, the differences here reveal how conflicted people may have been about the issue and how quickly opinions might shift — as they did. Remember, then, to be very careful in reviewing the wording of survey or poll questions.

Finally, always keep in mind that the date of a poll may strongly affect the results — and their usefulness in an argument. In 2010, for example, nearly 50 percent of California voters supported building more nuclear power plants. Less than a year later, that percentage had dropped to 37 percent after the meltdown of Japanese nuclear power plants in the wake of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. On public and political issues, you need to be sure that you are using timely information.

RESPOND •

Choose an important issue and design a series of questions to evoke a range of responses in a poll. Try to design a question that would make people strongly inclined to agree, another question that would lead them to oppose the same proposition, and a third that tries to be more neutral. Then try out your questions on your classmates.

Amy Stretten shares her personal experience with prejudice to strengthen her argument in “Appropriating Native American Imagery Honors No One but the Prejudice.”

Testimonies and Narratives

Writers can support arguments by presenting human experiences in the form of narrative or testimony — particularly if those experiences are their own. In courts, judges and juries often take into consideration detailed descriptions and narratives of exactly what occurred. Look at this reporter’s account of a court case in which a panel of judges decided, based on the testimony presented, that a man had been sexually harassed by another man. The narrative, in this case, supplies the evidence:

The Seventh Circuit, in a 1997 case known as Doe v. City of Belleville, drew a sweeping conclusion allowing for same-sex harassment cases of many kinds. . . . This case, for example, centered on teenage twin brothers working a summer job cutting grass in the city cemetery of Belleville, Ill. One boy wore an earring, which caused him no end of grief that particular summer — including a lot of menacing talk among his coworkers about sexually assaulting him in the woods and sending him “back to San Francisco.” One of his harassers, identified in court documents as a large former marine, culminated a verbal campaign by backing the earring-wearer against a wall and grabbing him by the testicles to see “if he was a girl or a guy.” The teenager had been “singled out for this abuse,” the court ruled, “because the way in which he projected the sexual aspect of his personality” — meaning his gender — “did not conform to his coworkers’ view of appropriate masculine behavior.”

— Margaret Talbot, “Men Behaving Badly”

Personal perspectives can support a claim convincingly and logically, especially if a writer has earned the trust of readers. In arguing that Tea Party supporters of a government shutdown in 2011 had no business being offended when some opponents described them as “terrorists,” Froma Harrop, one of the writers who used the term, argued logically and from experience why the characterization was appropriate:

[T]he hurt the tea party writers most complained of was to their feelings. I had engaged in name-calling, they kept saying. One professing to want more civility in our national conversation, as I do, should not be flinging around the terrorist word.

May I presume to disagree? Civility is a subjective concept, to be sure, but hurting people’s feelings in the course of making solid arguments is fair and square. The decline in the quality of our public discourse results not so much from an excess of spleen, but a deficit of well-constructed arguments. Few things upset partisans more than when the other side makes a case that bats home.

“Most of us know that effectively scoring on a point of argument opens us to the accusation of mean-spiritedness,” writes Frank Partsch, who leads the National Conference of Editorial Writers’ Civility Project. “It comes with the territory, and a commitment to civility should not suggest that punches will be pulled in order to avoid such accusations.”

— Froma Harrop, “Hurt Feelings Can Be a Consequence of Strong Arguments”

This narrative introduction gives a rationale for supporting the claim Harrop is making: we can expect consequences when we argue ineffectively. (For more on establishing credibility with readers, see Chapter 3.)

RESPOND •

Bring to class a full review of a recent film that you either enjoyed or did not enjoy. Using testimony from that review, write a brief argument to your classmates explaining why they should see that movie (or why they should avoid it), being sure to use evidence from the review fairly and reasonably. Then exchange arguments with a classmate, and decide whether the evidence in your peer’s argument helps to change your opinion about the movie. What’s convincing about the evidence? If it doesn’t convince you, why doesn’t it?