Appropriating Native American Imagery Honors No One but the Prejudice

Amy Stretten, a member of the Chickahominy Tribe of Virginia, is a Florida-based bilingual (Spanish/English) multimedia consultant and producer whose focus is helping public and private entities successfully deal with the challenges of being part of a diverse, multicultural country and world. This technology-enriched essay appeared on the Web site Fusion in late 2013. As you’ll note, much of Stretten’s evidence for her claims is only a click away; we’ve provided a URL (paragraph 13) to help you find the evidence she is drawing on as she makes her argument. As you read Stretten’s essay, consider the interesting ways in which she combines personal experience with artistic and inartistic proofs to support her claims. (If these terms are unfamiliar to you, check out Chapter 4 on arguments based on fact and reason.)

Appropriating Native American Imagery Honors No One but the Prejudice

AMY STRETTEN

Sept. 18, 2013

I was a sophomore in high school, about fifteen years old, when a rather hostile group of cheerleaders and football players cornered me, yelling, as I sat on a bench in the quad between classes. “Don’t you have school pride?” a cheerleader shouted. “You should feel proud! We’re honoring your people!” one football player hollered.

I was the only Native American (as far as I knew) at Woodbridge High School in Irvine, California. Irvine is a planned city in Southern California and one of the safest cities in the United States, but I didn’t feel safe that day.

I had met one-on-one with the principal, my guidance counselor, a few teachers, and several students to share my negative feelings toward our school’s mascot — an anonymous Native American “warrior” with long, flowing, jet-black hair, a large nose, and huge muscles. I guess I thought if I made it known that I felt appropriating Native American imagery was offensive, they’d stop. I was outnumbered, though, and my personal feelings didn’t matter. But that’s the thing: as Native people, especially as urban Natives (what we Indigenous people living in urban centers call ourselves), we are almost always outnumbered. So, we go unnoticed and unheard. Our opinions never really matter.

Students wore goofy, cartoonish costumes of our mascot (and his equally tasteless “warrior princess” girlfriend) at pep rallies and games. The pair would dance and do occasional acrobatic moves, as they made their grand entrance to the deafening sounds of the school’s marching band, playing the quintessential Hollywood fight song that, for me at least, conjures up images of a scene from an old Western movie: “savage” Indians on horseback approaching a village of settlers . . . Uh-oh, there must be trouble.

5 Spectators always stood for the song and sliced the air with their arms. I’m sure you’ve seen it, or done it yourself — the tomahawk chop. Every now and then you’d hear a distant war whoop. And if you were lucky, you’d get to see an imitation of war paint on game day.

I didn’t understand how face paint purchased from a drug store and a faux headdress made of brown construction paper and dyed arts & crafts feathers was respect. How does celebrating Native people with war imagery honor a living people? Well, it doesn’t. It saddens me that this is all we are to you: people who speak in broken English (“How.”) and the only thing we do is engage in battle with bows, arrows, and tomahawks. Oh, and perform an occasional rain dance when we hear a repetitive drum beat.

Racial stereotyping, inaccurate racial portrayals, and cultural appropriation do not honor a living breathing people. Plain and simple, cultural appropriation — especially when members of the culture protest the appropriation — is not respectful.

It’s beyond me why people are okay with this. With any other culture, people would be up in arms.

Maybe the Woodbridge High School community and others don’t understand how this type of bullying — yes, it’s bullying — affects young people. Native American and Alaskan Native youth have the highest rates of suicide-related fatalities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The lack of positive images of Native Americans doesn’t help self-esteem.

10 I’m not the only one who thinks that racist mascots don’t belong in sports. Just ask a psychologist.

The American Psychology Association (APA) recommends retiring American Indian mascots altogether. First of all, the organization found that the stereotypical images were harmful for the development and self-esteem of American Indian students. That wasn’t all. The portrayals had a negative effect on all students.

The problem, according to the APA, is that American Indian mascots are “undermining the educational experiences of members of all communities — especially those who have had little or no contact with Indigenous peoples.” And, it “establishes an unwelcome and often times hostile learning environment for American Indian students that affirms negative images/stereotypes that are promoted in mainstream society.”

One of the best films on the subject that I’ve seen is the documentary film In Whose Honor?. The film focuses on Charlene Teters (Spokane) and her campaign against “Chief Illiniwek,” the mascot of University of Illinois. Other highly publicized Native American mascot battles are described here: http://abcnews.go.com/US/sports-mascots-stir-controversy/story?id=20194389.

Unfortunately, this racial insensitivity extends beyond U.S. borders. Ian Campeau, an Ojibway father and member of the DJ group, A Tribe Called Red, has filed a human rights complaint with the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal against an amateur football club, the Nepean “Redskins,” in hopes of eradicating the use of the term altogether. The team is based in Canada’s capital city, Ottawa, and uses a cartoon image of a red-faced Indian man with a large nose, a long, black braid, and two feathers in his hair as their mascot.

15 “The players call each other ‘redskins’ on the field,” said Campeau in a press release. “How are they going to differentiate the playing field from the school yard? What’s going to stop them from calling my daughter a redskin in the schoolyard? That’s as offensive as using the n-word.”

If Campeau’s request is granted, the Human Rights Tribunal would order the National Capital Amateur Football Association to change the name and logo. His complaint also requests that the Tribunal draft a policy on the use of Indigenous imagery in sports, which could have an impact on teams of various levels that use the Redskins name in Canada.

The most in-your-face examples of racist mascots are in professional sports, including the football team of our nation’s capital, the Washington Redskins. The team’s owner, Dan Snyder, refuses to change the team’s name despite the obvious offensive nature of the imagery and name itself. Snyder has been quoted as saying, “We’ll never change it. It’s that simple. NEVER — you can use caps.”

Well, to anyone else who believes in turning a marginalized group of people into a goofy caricature, I’d like to ask: Who asked you to honor me? Let alone in this way? Cultural exploitation for profit in the name of respect is not how you honor a minority group. You honor someone important with a building named in their honor, a street named after them, a scholarship fund in their name, or a key to the city — not a sports mascot.

In 2001, after facing increased pressure from the Southern California Indian Center and others, Irvine Unified School District decided to retire Woodbridge High School’s Warrior mascot and imagery. The school would paint over the huge mural on the side of the gym of the anonymous Native American warrior and they would remove it from the gym floor. The L.A. Times reported on it.

20 But racism dies hard. In 2009, eight years later, my mother was forced to contact the school district due to cyber-bullying my sister, who is nine years younger, faced while a student at Woodbridge. A group of students who were in favor of the Warrior mascot created a Facebook campaign called “Save Our Warrior Mascot” and several members of the group wanted to find out who the sophomore girl opposed to the mascot was and “teach her a lesson.” (Their words.)

Last year was my ten-year high school reunion, and despite making close friendships with some classmates, I decided not to attend primarily because one former classmate suggested they get together to repaint the warrior face on the exterior of the gym.

The name Redskins is offensive to many, but my beef is not just with the name. It’s with the imagery. When can we let go of our need to own Native American imagery?

RESPOND •

Stretten makes a complex argument that does not mince words, claiming that Native mascots are harmful to both Native Americans and Americans who are not Native. In particular, she links mascots with bullying in schools — a hot topic in 2013 — and raises what are ultimately profound questions about ownership of images. Did Stretten challenge you to think about this issue in new ways? Why or why not?

How and where does Stretten use personal experience to good effect in this essay? Reread the essay, marking the passages where Stretten relies on personal experience. How would the essay be different if those passages were omitted? (If you find this question challenging, look up “personal experience” in the book’s index, and you’ll find discussions in several chapters of its use and power.)

As the headnote points out, Stretten does not rely uniquely on personal experience, however. What other sorts of evidence does she present? (Again, Chapter 4 may help you out here.) Visit the URL link in paragraph 13 of this article to determine whether Stretten uses online sources in fair and appropriate ways. (Chapters 18–20, which deal with aspects of finding, evaluating, and using sources appropriately, may be helpful here.)

Stretten’s essay raises complex questions about who owns or should own the past and the present. Characterize her position on these questions, making explicit as best you can her reasoning for her position. Where, exactly, do stereotypes play into these questions? (Chapter 7 on structuring arguments may prove useful here.)

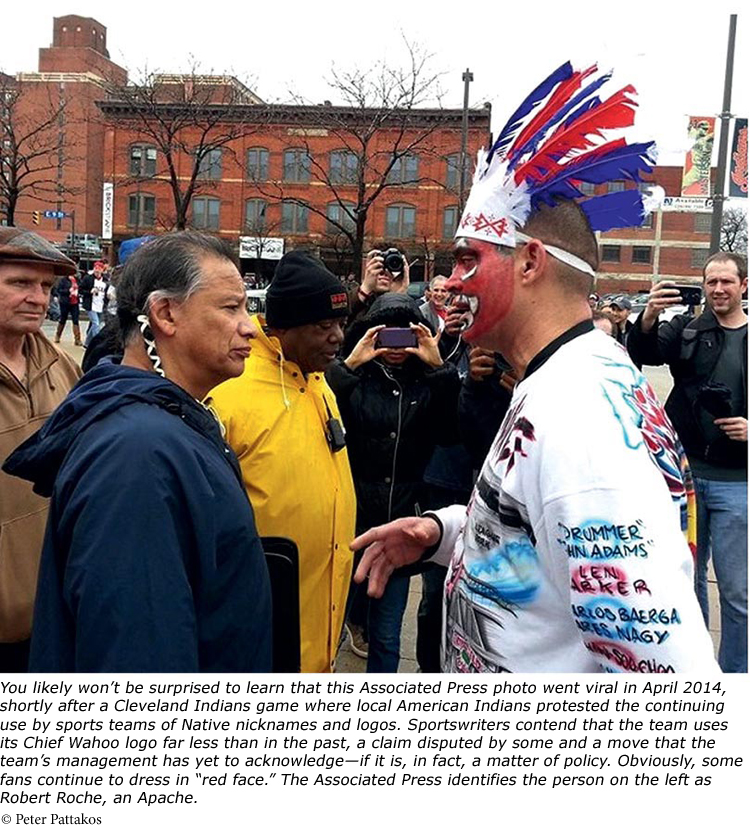

Write an extended dialogue between the two Americans pictured in the photo accompanying this article: Robert Roche, a Native American who is Apache, and the sports fan, who is not Native American (or, certainly, that is the assumption that everyone who reposted or retweeted this image made, and it is likely a safe one for many reasons). In the dialogue, you’ll obviously want to construct an argument, likely a proposal argument. You will need to determine whether your goal is to construct a Rogerian or an invitational argument, one that builds on common ground (see Chapter 7) or one that offers no room for compromise.

Write a proposal essay in which you tackle the issues Stretten raises but with a focus on another debate about stereotypical representations. The mascots for college football teams have often been controversial, but there are certainly other issues: the statues that do (and do not) grace the campuses of colleges across the country; the Confederate flag; the presence of crosses, statues representing the Ten Commandments, or menorahs; the Muslim call to prayer played over loudspeakers; and the representation of various groups in television cartoons or programs. As in all strong proposal arguments, you’ll need to acknowledge and discuss perspectives other than the one you put forward. (See Chapter 12 on proposal arguments for assistance with this assignment.)