Fallacies of Logical Argument

Fallacies of Logical Argument

You’ll encounter a problem in any argument when the claims, warrants, or proofs in it are invalid, insufficient, or disconnected. In theory, such problems seem easy enough to spot, but in practice, they can be camouflaged by a skillful use of words or images. Indeed, logical fallacies pose a challenge to civil argument because they often seem reasonable and natural, especially when they appeal to people’s self-interests.

Hasty Generalization

A hasty generalization is an inference drawn from insufficient evidence: because my Fiat broke down, then all Fiats must be junk. It also forms the basis for most stereotypes about people or institutions: because a few people in a large group are observed to act in a certain way, all members of that group are inferred to behave similarly. The resulting conclusions are usually sweeping claims of little merit: women are bad drivers; men are slobs; English teachers are nitpicky; computer jocks are . . . , and on and on.

To draw valid inferences, you must always have sufficient evidence (see Chapter 18) and you must qualify your claims appropriately. After all, people do need generalizations to make reasonable decisions in life. Such claims can be offered legitimately if placed in context and tagged with sensible qualifiers — some, a few, many, most, occasionally, rarely, possibly, in some cases, under certain circumstances, in my limited experience.

Faulty Causality

In Latin, faulty causality is known as post hoc, ergo propter hoc, which translates as “after this, therefore because of this” — the faulty assumption that because one event or action follows another, the first causes the second. Consider a lawsuit commented on in the Wall Street Journal in which a writer sued Coors (unsuccessfully), claiming that drinking copious amounts of the company’s beer had kept him from writing a novel.

Some actions do produce reactions. Step on the brake pedal in your car, and you move hydraulic fluid that pushes calipers against disks to create friction that stops the vehicle. In other cases, however, a supposed connection between cause and effect turns out to be completely wrong. For example, doctors now believe that when an elderly person falls and breaks a hip or leg, the injury usually caused the fall rather than the other way around.

That’s why overly simple causal claims should always be subject to scrutiny. In summer 2008, writer Nicholas Carr posed a simple causal question in a cover story for the Atlantic: “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” Carr essentially answered yes, arguing that “as we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens” and that the more one is online the less he or she is able to concentrate or read deeply.

But others, like Jamais Cascio (senior fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies), soon challenged that causal connection: rather than making us stupid, Cascio argues, Internet tools like Google will lead to the development of “‘fluid intelligence’ — the ability to find meaning in confusion and to solve new problems, independent of acquired knowledge.” The final word on this contentious causal relationship — the effects on the human brain caused by new technology — has yet to be written, and will probably be available only after decades of complicated research.

Begging the Question

Most teachers have heard some version of the following argument: You can’t give me a C in this course; I’m an A student. A member of Congress accused of taking kickbacks can make much the same argument: I can’t be guilty of accepting such bribes; I’m an honest person. In both cases, the claim is made on grounds that can’t be accepted as true because those grounds themselves are in question. How can the accused bribe-taker defend herself on grounds of honesty when that honesty is in doubt? Looking at the arguments in Toulmin terms helps to see the fallacy:

| Claim | You can’t give me a C in this course . . . |

| Reason | . . . because I’m an A student. |

| Warrant | An A student is someone who can’t receive Cs. |

| Claim | Representative X can’t be guilty of accepting bribes . . . |

| Reason | . . . because she’s an honest person. |

| Warrant | An honest person cannot be guilty of accepting bribes. |

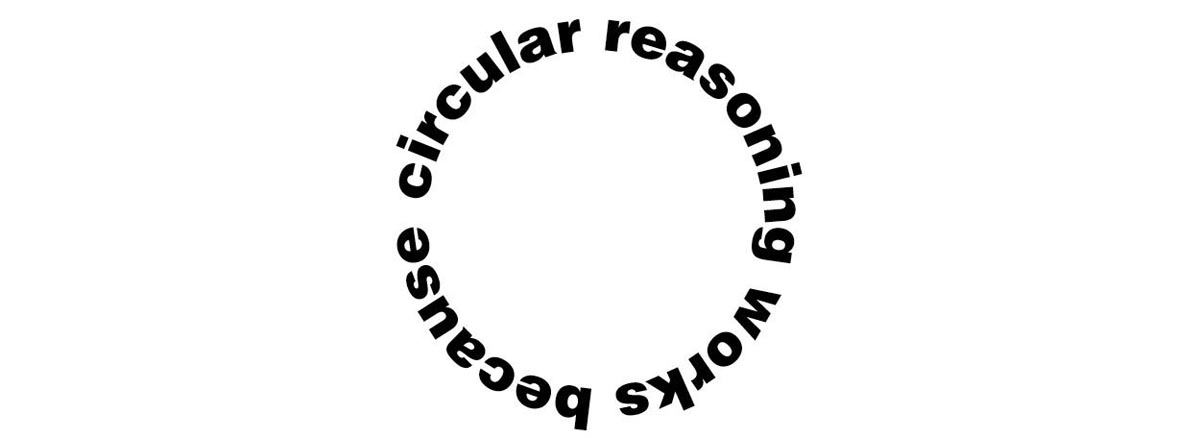

With the warrants stated, you can see why begging the question — assuming as true the very claim that’s disputed — is a form of circular argument that goes nowhere. (For more on Toulmin argument, see Chapter 7.)

Equivocation

Equivocations — half truths or arguments that give lies an honest appearance — are usually based on tricks of language. Consider the plagiarist who copies a paper word for word from a source and then declares that “I wrote the entire paper myself” — meaning that she physically copied the piece on her own. But the plagiarist is using wrote equivocally and knows that most people understand the word to mean composing and not merely copying words.

Parsing words carefully can sometimes look like equivocation or be the thing itself. For example, early in 2014 Internal Revenue Service Commissioner John Koskinen promised to turn over to a committee of the House of Representatives all the relevant emails in a scandal involving the agency. Subsequently, the agency revealed that some of those requested emails had been destroyed by the failure of a computer’s hard drive. But Koskinen defended his earlier promise by telling the chair of the committee, “I never said I would provide you emails we didn’t have.” A simple statement of fact or a slick equivocation?

Non Sequitur

A non sequitur is an argument whose claims, reasons, or warrants don’t connect logically. You’ve probably detected a non sequitur when you react to an argument with a puzzled, “Wait, that doesn’t follow.” Children are adept at framing non sequiturs like this one: You don’t love me or you’d buy me a new bicycle! It doesn’t take a parental genius to realize that love has little connection with buying children toys.

Non sequiturs often occur when writers omit steps in an otherwise logical chain of reasoning. For example, it might be a non sequitur to argue that since postsecondary education now costs so much, it’s time to move colleges and university instruction online. Such a suggestion may have merit, but a leap from brick-and-mortar schools to virtual ones is extreme. Numerous issues and questions must be addressed step-by-step before the proposal can be taken seriously.

Politicians sometimes resort to non sequiturs to evade thorny issues or questions. Here for example is presidential candidate Mitt Romney in a 2011 CNBC Republican primary debate turning moderator John Harwood’s question about changing political positions into one about demonstrating personal integrity:

Harwood: . . . Your opponents have said you switched positions on many issues. . . . What can you say to Republicans to persuade them that the things you say in the campaign are rooted in something deeper than the fact that you are running for office?

Romney: John, I think people know me pretty well. . . . I think people understand that I’m a man of steadiness and constancy. I don’t think you are going to find somebody who has more of those attributes than I do. I have been married to the same woman for . . . 42 years. . . . I have been in the same church my entire life.

Conservative writer Matt K. Lewis took Romney to task for this move, pointing out that a steady personal life is no guarantor of a consistent political philosophy:

This, of course, is not to say that values and character do not matter — they do — but it is to say that Romney’s answer was a non sequitur. Everyone knows Mitt Romney is a decent, respectable person. The question is whether or not he can be trusted to advance conservatism as president.

Straw Man

Those who resort to the straw man fallacy attack arguments that no one is really making or portray opponents’ positions as more extreme or far less coherent than they actually are. The speaker or writer thus sets up an argument that is conveniently easy to knock down (like a man of straw), proceeds to do so, and then claims victory over an opponent who may not even exist.

Straw men are especially convenient devices for politicians who want to characterize the positions of their opponents as more extreme than they actually are: consider obvious memes such as “war on women” and “war on Christmas.” But straw man arguments are often more subtle. For instance, Steven Novella of Yale University argues that political commentator Charles Krauthammer slips into the fallacy when he misconstrues the meaning of “settled science” in a column on climate change. Novella rebuts Krauthammer’s assertion that “There is nothing more anti-scientific than the very idea that science is settled, static, impervious to challenge” by explaining why such a claim is deceptive:

Calling something an established scientific fact means that it is reasonable to proceed with that fact as a premise, for further research or for policy. It does not mean “static, impervious to challenge.” That is the straw man. Both evolution deniers and climate change deniers use this tactic to misinterpret scientific confidence as an anti-scientific resistance to new evidence or arguments. It isn’t. It does mean that the burden of proof has shifted to those opposing the theory that is now well-established (because it has already met a significant burden of proof).

— Steven Novella, NeuroLogica Blog, February 25, 2014

In other words, Krauthammer’s definition of science is not one that most scientists use.

Red Herring

This fallacy gets its name from the old British hunting practice of dragging a dried herring across the path of the fox in order to throw the hounds off the trail. A red herring fallacy does just that: it changes the subject abruptly or introduces an irrelevant claim or fact to throw readers or listeners off the trail. For example, people skeptical about climate change will routinely note that weather is always changing and point to the fact that Vikings settled in Greenland one thousand years ago before harsher conditions drove them away. True, scientists will say, but the point is irrelevant to arguments about worldwide global warming caused by human activity.

The red herring is not only a device writers and speakers use in the arguments they create, but it’s also a charge used frequently to undermine someone else’s arguments. Couple the term “red herring” in a Web search to just about any political or social cause and you’ll come up with numerous articles complaining of someone’s use of the device.

climate change + red herring

common core + red herring

immigration reform + red herring

“Red herring” has become a convenient way of saying “I disagree with your argument” or “your point is irrelevant.” And perhaps making a too-easy rebuttal like that can itself be a fallacy?

Faulty Analogy

Comparisons can help to clarify one concept by measuring it against another that is more familiar. Consider the power and humor of this comparison attributed to Mark Twain, an implicit argument for term limits in politics:

Politicians and diapers must be changed often, and for the same reason.

When comparisons such as this one are extended, they become analogies — ways of understanding unfamiliar ideas by comparing them with something that’s better known (see “Analogies” in Chapter 4, “Arguments Based on Facts and Reason: Logos”). But useful as such comparisons are, they may prove false if either taken on their own and pushed too far, or taken too seriously. At this point, they turn into faulty analogies — inaccurate or inconsequential comparisons between objects or concepts. Economist Paul Krugman provides an eye-opening analysis of a familiar but, as he sees it, false analogy between personal and government debt:

Deficit-worriers portray a future in which we’re impoverished by the need to pay back money we’ve been borrowing. They see America as being like a family that took out too large a mortgage, and will have a hard time making the monthly payments.

This is, however, a really bad analogy in at least two ways.

First, families have to pay back their debt. Governments don’t — all they need to do is ensure that debt grows more slowly than their tax base. The debt from World War II was never repaid; it just became increasingly irrelevant as the U.S. economy grew, and with it the income subject to taxation.

Second — and this is the point almost nobody seems to get — an overborrowed family owes money to someone else; U.S. debt is, to a large extent, money we owe to ourselves.

Whether you agree with the Nobel laureate or not, his explanation offers insight into how analogies work (or fail) and how to think about them critically.

RESPOND •

Examine each of the following political slogans or phrases for logical fallacies.

“Resistance is futile.” (Borg message on Star Trek: The Next Generation)

“It’s the economy, stupid.” (sign on the wall at Bill Clinton’s campaign headquarters)

“Make love, not war.” (antiwar slogan popularized during the Vietnam War)

“A chicken in every pot.” (campaign slogan)

“Guns don’t kill, people do.” (NRA slogan)

Page 86“Dog Fighters Are Cowardly Scum.” (PETA T-shirt)

“If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” (attributed to Harry S Truman)

Choose a paper you’ve written for a college class and analyze it for signs of fallacious reasoning. Then find an editorial, a syndicated column, and a news report on the same topic and look for fallacies in them. Which has the most fallacies — and what kind? What may be the role of the audience in determining when a statement is fallacious?

Find a Web site that is sponsored by an organization (the Future of Music Coalition, perhaps), a business (Coca-Cola, Pepsi), or another group (the Democratic or Republican National Committee), and analyze the site for fallacious reasoning. Among other considerations, look at the relationship between text and graphics and between individual pages and the pages that surround or are linked to them.

Political blogs such as Mother Jones and InstaPundit typically provide quick responses to daily events and detailed critiques of material in other media sites, including national newspapers. Study one such blog for a few days to see whether and how the site critiques the articles, political commentary, or writers it links to. Does the blog ever point out fallacies of argument? If so, does it explain the problems with such reasoning or just assume readers will understand the fallacies? Summarize your findings in a brief oral report to your class.