Understanding Arguments of Fact

Understanding Arguments of Fact

Factual arguments come in many varieties, but they all try to establish whether something is or is not so, answering questions such as Is a historical legend true? Has a crime occurred? or Are the claims of a scientist accurate? At first glance, you might object that these aren’t arguments at all but just a matter of looking things up and then writing reports. And you’d be correct to an extent: people don’t usually argue factual matters that are settled or undisputed (The earth revolves around the sun), that might be decided with simple research (The Mendenhall Glacier has receded 1.75 miles since 1958), or that are the equivalent of a rule (One mile measures 5,280 feet). Reporting facts, you might think, should be free of the friction of argument.

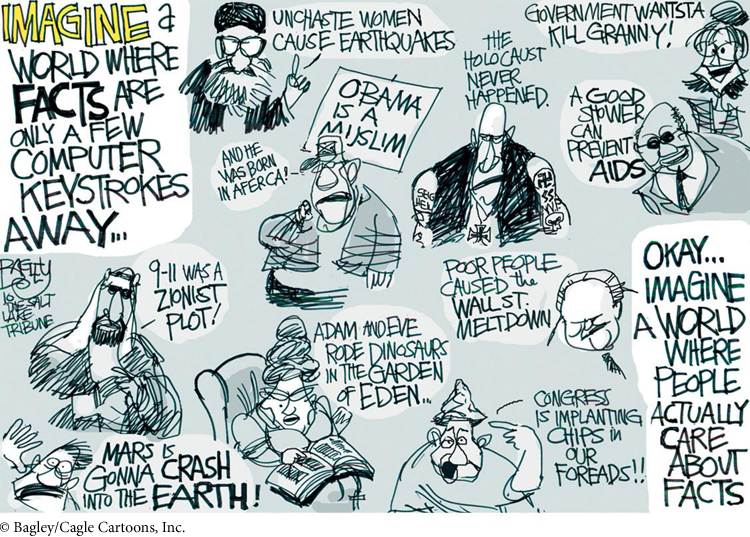

Yet facts become arguments whenever they’re controversial on their own or challenge people’s beliefs and lifestyles. Disagreements about childhood obesity, endangered species, or energy production ought to have a kind of clean, scientific logic to them. But that’s rarely the case because the facts surrounding them must be interpreted. Those interpretations then determine what we feed children, where we can build a dam, or how we heat our homes. In other words, serious factual arguments almost always have consequences. Can we rely on wind and solar power to solve our energy needs? Will the Social Security trust fund really go broke? Is it healthy to eat fatty foods? People need well-reasoned factual arguments on subjects of this kind to make informed decisions. Such arguments educate the public.

For the same reason, we need arguments to challenge beliefs that are common in a society but held on the basis of inadequate or faulty information. Corrective arguments appear daily in the media, often based on studies written by scientists or researchers that the public would not encounter on their own. Many people, for example, believe that talking on a cell phone while driving is just like listening to the radio. But their intuition is not based on hard data: scientific studies show that using a cell phone in a car is comparable to driving under the influence of alcohol. That’s a fact. As a result, fourteen states (and counting) have banned the use of handheld phones in cars.

Factual arguments also routinely address broad questions about how we understand the past. For example, are the accounts that we have of the American founding — or the Civil War, Reconstruction, or the heroics of the “Greatest Generation” in World War II — accurate? Or do the “facts” that we teach today sometimes reflect the perspectives and prejudices of earlier times or ideologies? The telling of history is almost always controversial and rarely settled: the British and Americans will always tell different versions of what happened in North America in 1776.

The Internet puts mountains of information at our fingertips, but we need to be sure to confirm whether or not that information is fact, using what Howard Rheingold calls “crap detection,” the ability to distinguish between accurate information and inaccurate information, misinformation, or disinformation. (For more on “crap detection,” see Chapter 19, “Evaluating Sources.”)

As you can see, arguments of fact do much of the heavy lifting in our world. They report on what has been recently discovered or explore the implications of that new information. They also add interest and complexity to our lives, taking what might seem simple and adding new dimensions to it. In many situations, they’re the precursors to other forms of analysis, especially causal and proposal arguments. Before we can explore why things happen as they do or solve problems, we need to do our best to determine the facts.

RESPOND •

For each topic in the following list, decide whether the claim is worth arguing to a college audience, and explain why or why not.

Earthquakes are increasing in number and intensity.

Many people die annually of heart disease.

Fewer people would be obese if they followed the Paleo Diet.

Japan might have come to terms more readily in 1945 if the Allies in World War II hadn’t demanded unconditional surrender.

Boys would do better in school if there were more men teaching in elementary and secondary classrooms.

The sharp drop in oil prices could lead drivers to go back to buying gas-guzzling trucks and SUVs.

There aren’t enough high-paying jobs for college graduates these days.

Hydrogen may never be a viable alternative to fossil fuels because it takes too much energy to change hydrogen into a usable form.

Proponents of the Keystone Pipe Line have exaggerated the benefits it will bring to the American economy.