Developing a Definitional Argument

Developing a Definitional Argument

Definitional arguments don’t just appear out of the blue; they often evolve out of daily life. You might get into an argument over the definition of ordinary wear and tear when you return a rental car with some soiled upholstery. Or you might be asked to write a job description for a new position to be created in your office: you have to define the job position in a way that doesn’t step on anyone else’s turf. Or maybe employees on your campus object to being defined as temporary workers when they’ve held their same jobs for years. Or someone derides one of your best friends as just a nerd. In a dozen ways every day, you encounter situations that are questions of definition. They’re so frequent and indispensable that you barely notice them for what they are.

Formulating Claims

In addressing a question of definition, you’ll likely formulate a tentative claim — a declarative statement that represents your first response to such situations. Note that such initial claims usually don’t follow a single definitional formula.

Claims of Definition

A person paid to do public service is not a volunteer.

Institutional racism can exist — maybe even thrive — in the absence of overt civil rights violations.

Political bias has been consistently practiced by the mainstream media.

Theatergoers shouldn’t confuse musicals with operas.

White lies are hard to define but easy to recognize.

None of the statements listed here could stand on its own because it likely reflects a first impression and gut reaction. But that’s fine because making a claim of definition is typically a starting point, a cocky moment that doesn’t last much beyond the first serious rebuttal or challenge. Statements like these aren’t arguments until they’re attached to reasons, data, warrants, and evidence (see Chapter 7).

Finding good reasons to support a claim of definition usually requires formulating a general definition by which to explore the subject. To be persuasive, the definition must be broad and not tailored to the specific controversy:

A volunteer is . . .

Institutional racism is . . .

Political bias is . . .

A musical is . . . but an opera is . . .

A white lie is . . .

Now consider how the following claims might be expanded with a general definition to become full-fledged definitional arguments:

Arguments of Definition

Someone paid to do public service is not a volunteer because volunteers are people who . . .

Institutional racism can exist even in the absence of overt violations of civil rights because, by definition, institutional racism is . . .

Political bias in the media is evident when . . .

Musicals focus on words first while operas . . .

The most important element of a white lie is its destructive nature; the act of telling one hurts both the receiver and the sender.

Notice, too, that some of the issues can involve comparisons between things — such as operas and musicals.

Crafting Definitions

Imagine that you decide to tackle the concept of paid volunteer in the following way:

Participants in the federal AmeriCorps program are not really volunteers because they receive “education awards” for their public service. Volunteers are people who work for a cause without receiving compensation.

In Toulmin terms, as explained in Chapter 7, the argument looks like this:

| Claim | Participants in AmeriCorps aren’t volunteers . . . |

| Reason | . . . because they are paid for their service. |

| Warrant | People who are compensated for their services are, ordinarily, employees. |

As you can see, the definition of volunteers will be crucial to the shape of the argument. In fact, you might think you’ve settled the matter with this tight little formulation. But now it’s time to listen to the readers over your shoulder (again, see Chapter 7), who are pushing you further. Do the terms of your definition account for all pertinent cases of volunteerism — in particular, any related to the types of public service AmeriCorps members might be involved in? What do you do with unpaid interns: how do they affect your definition of volunteers? Consider, too, the word cause in your original claim of the definition:

Volunteers are people who work for a cause without receiving compensation.

Cause has political connotations that you may or may not intend. You’d better clarify what you mean by cause when you discuss its definition in your paper. Might a phrase such as the public good be a more comprehensive or appropriate substitute for a cause? And then there’s the matter of compensation in the second half of your definition:

Volunteers are people who work for a cause without receiving compensation.

Aren’t people who volunteer to serve on boards, committees, and commissions sometimes paid, especially for their expenses? What about members of the so-called all-volunteer military? They’re financially compensated during their years of service, and they enjoy benefits after they complete their tours of duty.

As you can see, you can’t just offer up a definition as part of an argument and expect that readers will accept it. Every part of a definition has to be interrogated, critiqued, and defended. So investigate your subject in the library, on the Internet, and in conversation with others, including experts if you can. You might then be able to present your definition in a single paragraph, or you may have to spend several pages coming to terms with the complexity of the core issue.

After conducting research of this kind, you’ll be in a better position to write an extended definition that explains to your readers what you believe makes a volunteer a volunteer, how to identify institutional racism, or how to distinguish between a musical and an opera.

Matching Claims to Definitions

Once you’ve formulated a definition that readers will accept — a demanding task in itself — you might need to look at your particular subject to see if it fits your general definition. It should provide evidence of one of the following:

It is a clear example of the class defined.

It clearly falls outside the defined class.

It falls between two closely related classes or fulfills some conditions of the defined class but not others.

It defies existing classes and categories and requires an entirely new definition.

How do you make this key move in an argument? Here’s an example from an article by Anthony Tommasini entitled “Opera? Musical? Please Respect the Difference.” Early in the piece, Tommasini argues that a key element separates the two musical forms:

Both genres seek to combine words and music in dynamic, felicitous and, to invoke that all-purpose term, artistic ways. But in opera, music is the driving force; in musical theater, words come first.

His claim of definition (or of difference) makes sense because it clarifies aspects of the two genres.

This explains why for centuries opera-goers have revered works written in languages they do not speak. . . . As long as you basically know what is going on and what is more or less being said, you can be swept away by a great opera, not just by music, but by visceral drama.

In contrast, imagine if the exhilarating production of Cole Porter’s Anything Goes now on Broadway . . . were to play in Japan without any kind of titling technology. The wit of the musical is embedded in its lyrics. . . .

But even after having found a distinction so perceptive, Tommasini (like most writers making arguments of definition) still has to acknowledge exceptions.

Theatergoing audiences may not care much whether a show is a musical or an opera. But the best achievements in each genre . . . have been from composers and writers who grounded themselves in a tradition, even while reaching across the divide. [emphasis added]

If evidence you’ve gathered while developing an argument of definition suggests that similar limitations may be necessary, don’t hesitate to modify your claim. It’s amazing how often seemingly cut-and-dried matters of definition become blurry — and open to compromise and accommodation — as you learn more about them. That has proved to be the case as various campuses across the country have tried to define hate speech or internship — tricky matters. And even the Supreme Court has never said exactly what pornography is. Just when matters seem to be settled, new legal twists develop. Should virtual child pornography created with software be illegal, as is the real thing? Or is a virtual image — even a lewd one — an artistic expression that is protected (as other works of art are) by the First Amendment?

Considering Design and Visuals

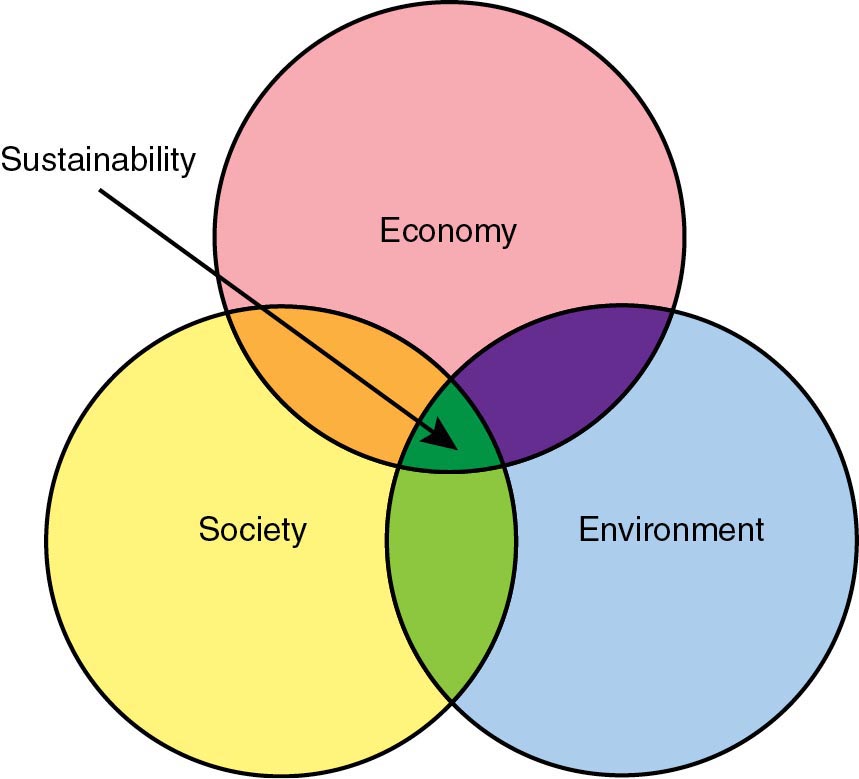

In thinking about how to present your argument of definition, you may find a simple visual helpful, such as the Venn diagram below from Wikimedia Commons that defines sustainability as the place where our society and its economy intersect with the environment. Such a visual might even suggest a structure for an oral presentation.

Remember too that visuals like photographs, charts, and graphs can also help you make your case. Such items might demonstrate that the conditions for a definition have been met — as the widely circulated and horrific photographs from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq helped to define torture. Or you might create a graphic yourself to illustrate a concept you are defining, perhaps through comparison and contrast.

Finally, don’t forget that basic design elements — such as boldface and italics, headings, or links in online text — can contribute to (or detract from) the credibility and persuasiveness of your argument of definition. (See Chapter 14 for more on “Visual Rhetoric.”)

See this diagram in context as one of the visuals supporting Christian R. Weisser’s definitional argument in “Sustainability,” from Sustainability: A Bedford Spotlight Reader