Developing Causal Arguments

Developing Causal Arguments

Exploring Possible Claims

To begin creating a strong causal claim, try listing some of the effects — events or phenomena — that you’d like to know the causes of:

Why do college tuition costs routinely outstrip the rate of inflation?

What’s really behind the slow pace of development of alternative energy sources?

Why are almost all the mothers in animated movies either dead to begin with or quickly killed off?

Page 249Why is same-sex marriage more acceptable to American society than it was a decade ago?

Why do so few younger Americans vote, even in major elections?

Or try moving in the opposite direction, listing some phenomena or causes you’re interested in and then hypothesizing what kinds of effects they may produce:

How will the growing popularity of e-readers change our relationships to books?

What will happen as the result of efforts to repeal the Affordable Health Care Act?

What will be the consequences if more liberal (or conservative) judges are appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court?

What will happen as China and India become dominant industrialized nations?

Read a little about the causal issues that interest you most, and then try them out on friends and colleagues. They might suggest ways to refocus or clarify what you want to do or offer leads to finding information about your subject. After some initial research, map out the causal relationship you want to explore in simple form:

X might cause (or might be caused by) Y for the following reasons:

(add more as needed)

Such a statement should be tentative because writing a causal argument should be an exercise in which you uncover facts, not assume them to be true. Often, your early assumptions (Tuition was raised to renovate the stadium) might be undermined by the facts you later discover (Tuition doesn’t fund the construction or maintenance of campus buildings).

You might even decide to write a wildly exaggerated or parodic causal argument for humorous purposes. Humorist Dave Barry does this when he explains the causes of El Niño and other weather phenomena: “So we see that the true cause of bad weather, contrary to what they have been claiming all these years, is TV weather forecasters, who have also single-handedly destroyed the ozone layer via overuse of hair spray.” Most of the causal reasoning you do, however, will take a serious approach to subjects that you, your family, and your friends care about.

RESPOND •

Working with a group, write a big Why? on a sheet of paper or computer screen, and then generate a list of why questions. Don’t be too critical of the initial list:

Why

— do people laugh?

— do swans mate for life?

— do college students binge drink?

— do teenagers drive fast?

— do babies cry?

— do politicians take risks on social media?

Generate as lengthy a list as you can in fifteen minutes. Then decide which of the questions might make plausible starting points for intriguing causal arguments.

Defining the Causal Relationships

In developing a causal claim, you can examine the various types of causes and effects in play in a given argument and define their relationship. Begin by listing all the plausible causes or effects you need to consider. Then decide which are the most important for you to analyze or the easiest to defend or critique. The following chart on “Causes” may help you to appreciate some important terms and relationships.

| Type of Causes | What It Is or Does | What It Looks Like |

|---|---|---|

|

Sufficient cause |

Enough for something to occur on its own |

Lack of oxygen is sufficient to cause death Cheating on an exam is sufficient to fail a course |

|

Necessary cause |

Required for something to occur (but in combination with other factors) |

Fuel is necessary for fire Capital is necessary for economic growth |

|

Precipitating cause |

Brings on a change |

Protest march ignites a strike by workers Plane flies into strong thunderstorms |

|

Proximate cause |

Immediately present or visible cause of action |

Strike causes company to declare bankruptcy Powerful wind shear causes plane to crash |

|

Remote cause |

Indirect or underlying explanation for action |

Company was losing money on bad designs and inept manufacturing Wind shear warning failed to sound in cockpit |

|

Reciprocal causes |

One factor leads to a second, which reinforces the first, creating a cycle |

Lack of good schools leads to poverty, which further weakens education, which leads to even fewer opportunities . . . |

Even the most everyday causal analysis can draw on such distinctions among reasons and causes. What persuaded you, for instance, to choose the college you decided to attend? Proximate reasons might be the location of the school or the college’s curriculum in your areas of interest. But what are the necessary reasons — the ones without which your choice of that college could not occur? Adequate financial support? Good test scores and academic record? The expectations of a parent?

Once you’ve identified a causal claim, you can draw out the reasons, warrants, and evidence that can support it most effectively:

Claim |

Certain career patterns cause women to be paid less than men. |

Reason |

Women’s career patterns differ from men’s. |

Warrant |

Successful careers are made during the period between ages twenty-five and thirty-five. |

Evidence |

Women often drop out of or reduce work during the decade between ages twenty-five and thirty-five to raise families. |

|

Claim |

Lack of community and alumni support caused the football coach to lose his job. |

Reason |

Ticket sales and alumni support have declined for three seasons in a row despite a respectable team record. |

Warrant |

Winning over fans is as important as winning games for college coaches in smaller athletic programs. |

Evidence |

Over the last ten years, coaches at several programs have been sacked because of declining support and revenues. |

RESPOND •

Here’s a schematic causal analysis of one event, exploring the difference among precipitating, necessary, and sufficient causes. Critique and revise the analysis as you see fit. Then create another of your own, beginning with a different event, phenomenon, incident, fad, or effect.

Event: Traffic fatality at an intersection

Precipitating cause: A pickup truck that runs a red light, totals a Prius, and injures its driver

Necessary cause: Two drivers who are navigating Friday rush-hour traffic (if no driving, then no accident)

Sufficient cause: A truck driver who is distracted by a cell-phone conversation

Supporting Your Point

In drafting your causal argument, you’ll want to do the following:

Show that the causes and effects you’ve suggested are highly probable and backed by evidence, or show what’s wrong with the faulty causal reasoning you may be critiquing.

Assess any links between causal relationships (what leads to or follows from what).

Show that your explanations of any causal chains are accurate, or identify where links in a causal chain break down.

Show that plausible cause-and-effect explanations haven’t been ignored or that the possibility of multiple causes or effects has been considered.

In other words, you will need to examine your subject carefully and find appropriate ways to support your claims. There are different ways to accomplish that goal.

For example, in studying effects that are physical (as they would be with diseases or climate conditions), you can offer and test hypotheses, or theories about possible causes. That means researching such topics thoroughly because you’ll need to draw upon authorities and research articles for your explanations and evidence. (See Chapter 17, “Academic Arguments,” and Chapter 18, “Finding Evidence.”) Don’t be surprised if you find yourself debating which among conflicting authorities make the most plausible causal or explanatory arguments. Your achievement as a writer may be simply that you present these differences in an essay, leaving it to readers to make judgments of their own — as John Tierney does in “Can a Playground Be Too Safe?” at the end of this chapter.

But not all the evidence in compelling causal arguments needs to be strictly scientific or scholarly. Many causal arguments rely on ethnographic observations — the systematic study of ordinary people in their daily routines. How would you explain, for example, why some people step aside when they encounter someone head-on and others do not? In an argument that attempts to account for such behavior, investigators Frank Willis, Joseph Gier, and David Smith observed “1,038 displacements involving 3,141 persons” at a Kansas City shopping mall. In results that surprised the investigators, “gallantry” seemed to play a significant role in causing people to step aside for one another — more so than other causes that the investigators had anticipated (such as deferring to someone who’s physically stronger or higher in status). Doubtless you’ve read of other such studies, perhaps in psychology courses. You may even decide to do a little fieldwork on your own — which raises the possibility of using personal experiences in support of a causal argument.

Indeed, people’s experiences generally lead them to draw causal conclusions about things they know well. Personal experience can also help build your credibility as a writer, gain the empathy of listeners, and thus support a causal claim. Although one person’s experiences cannot ordinarily be universalized, they can still argue eloquently for causal relationships. Listen to Sara Barbour, a recent graduate of Columbia University, as she draws upon her own carefully described experiences to bemoan what may happen when e-readers finally displace printed books:

In eliminating a book’s physical existence, something crucial is lost forever. Trapped in a Kindle, the story remains but the book can no longer be scribbled in, hoarded, burned, given, or received. We may be able to read it, but we can’t share it with others in the same way, and its ability to connect us to people, places, and ideas is that much less powerful.

I know the Kindle will eventually carry the day — an electronic reader means no more embarrassing coffee stains, no more library holds and renewals, no more frantic flipping through pages for a lost quote, or going to three bookstores in one afternoon to track down an evasive title. Who am I to advocate the doom of millions of trees when the swipe of a finger can deliver all 838 pages of Middlemarch into my waiting hands?

But once we all power up our Kindles something will be gone, a kind of language. Books communicate with us as readers — but as important, we communicate with each other through books themselves. When that connection is lost, the experience of reading — and our lives — will be forever altered.

— Sara Barbour, “Kindle vs. Books: The Dead Trees Society,” Los Angeles Times, June 17, 2011

All these strategies — testing hypotheses, presenting experimental evidence, and offering personal experience — can help you support a causal argument or undermine a causal claim you regard as faulty.

RESPOND •

One of the fallacies of argument discussed in Chapter 5 is the post hoc, ergo propter hoc (“after this, therefore because of this”) fallacy. Causal arguments are particularly prone to this kind of fallacious reasoning, in which a writer asserts a causal relationship between two entirely unconnected events. When Angelina Jolie gave birth to twins in 2008, for instance, the stock market rallied by nearly six hundred points, but it would be difficult to argue that either event is related to the other.

Because causal arguments can easily fall prey to this fallacy, you might find it instructive to create and defend an absurd connection of this kind. Begin by asserting a causal link between two events or phenomena that likely have no relationship: The enormous popularity of Doctor Who is partially due to global warming. Then spend a page or so spinning out an imaginative argument to defend the claim. It’s OK to have fun with this exercise, but see how convincing you can be at generating plausibly implausible arguments.

Considering Design and Visuals

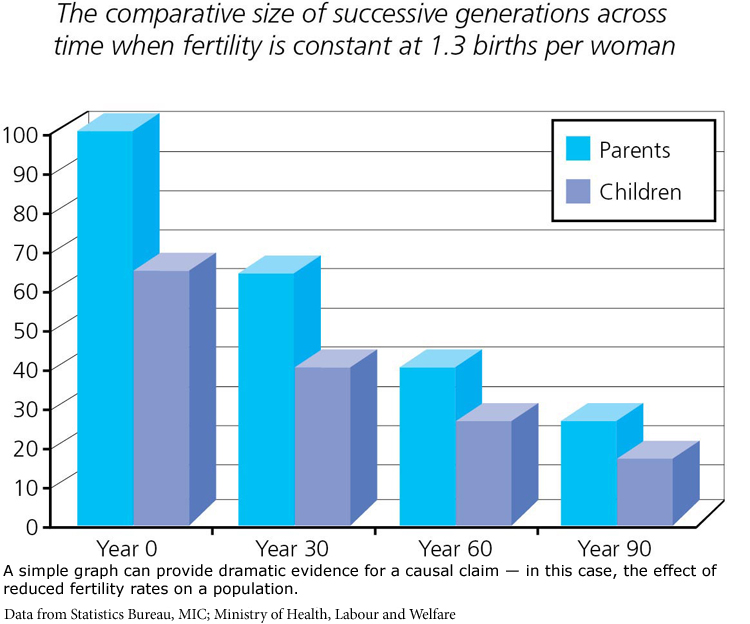

You may find that the best way to illustrate a causal relationship is to present it visually. Even a simple bar graph or chart can demonstrate a relationship between two variables that might be related to a specific cause, like the one above showing the dramatic effects of lowered birthrates. The report that uses this figure explores the effects that such a change would have on the economies of the world.

Or you may decide that the most dramatic way to present important causal information about a single issue or problem is via an infographic, cartoon, or public service announcement. Our arresting example below is part of a campaign by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). An organization that advocates for animal rights, PETA promotes campaigns that typically try to sway people to adopt vegetarian diets by depicting the practices of the agriculture industry as cruel. (Many of us have also seen their celebrity anti-fur campaigns; see “Examining Arguments Based on Facts and Reason: Logos” in Chapter 6, “Rhetorical Analysis” for one example.) Their “Meat’s Not Green!” campaign, however, attempts to reach an audience that might not buy into the animal rights argument. Instead, it appeals to people who have environmentalist beliefs by presenting data that claims a causal link between animal farming and environmental destruction. How much of this data surprises you?