Characterizing Proposals

Characterizing Proposals

Proposals have three main characteristics:

They call for change, often in response to a problem.

They focus on the future.

They center on the audience.

Proposals always call for some kind of action. They aim at getting something done — or sometimes at preventing something from being done. Proposals marshal evidence and arguments to persuade people to choose a course of action: Let’s build a completely green house. Let’s oppose the latest Supreme Court ruling on Internet privacy. Let’s create a campus organization for first-generation college students. Let’s ban drones from campus airspace, especially at sporting events. But you know the old saying, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.” It’s usually easier to convince audiences what a good course of action is than to persuade them to take it (or pay for it). Even if you present a cogent proposal, you may still have work to do.

What is Charles A. Riley II proposing in Disability and the Media: Prescriptions for Change? How does his argument center on the audience?

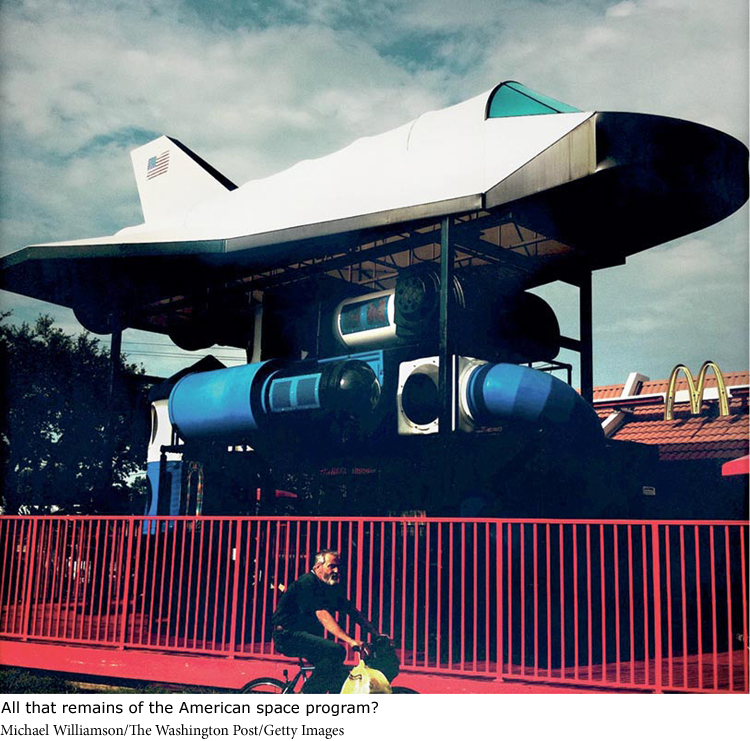

Proposal arguments must appeal to more than good sense. Ethos matters, too. It helps if a writer suggesting a change carries a certain gravitas earned by experience or supported by knowledge and research. If your word and credentials carry weight, then an audience is more likely to listen to your proposal. So when the commanders of three Apollo moon missions, Neil Armstrong, James Lovell, and Eugene Cernan, wrote an open letter to President Obama expressing their dismay at his administration’s decision to cancel NASA’s plans for advanced spacecraft and new lunar missions, they won a wide audience:

For The United States, the leading space faring nation for nearly half a century, to be without carriage to low Earth orbit and with no human exploration capability to go beyond Earth orbit for an indeterminate time into the future, destines our nation to become one of second or even third rate stature. While the President’s plan envisages humans traveling away from Earth and perhaps toward Mars at some time in the future, the lack of developed rockets and spacecraft will assure that ability will not be available for many years.

Without the skill and experience that actual spacecraft operation provides, the USA is far too likely to be on a long downhill slide to mediocrity. America must decide if it wishes to remain a leader in space. If it does, we should institute a program which will give us the very best chance of achieving that goal.

But even their considerable ethos was not enough to carry the day with the space agency and the man who made the decision.

Yet, as the space program example obviously demonstrates, proposal arguments focus on the future — what people, institutions, or governments should do over the upcoming weeks, months, or, in the NASA moon-mission example, decades. This orientation toward the future presents special challenges, since few of us have crystal balls. Proposal arguments must therefore offer the best evidence available to suggest that actions we recommend will achieve what they promise.

In May 2014, Senator Elizabeth Warren introduced legislation aimed at reducing student loan debt, in part by allowing for refinancing. In an interview in Rolling Stone, Senator Warren explained:

Homeowners refinance their loans when interest rates go down. Businesses refinance their loans. But right now, there’s no way for students to be able to do that. I’ve proposed that we reduce the interest rate on the outstanding loan debt to the same rate Republicans and Democrats came together last year to set on new loans [3.86 percent]. For millions of borrowers, that would cut interest rates in half or more.

Yet Warren’s proposal soon came under fire, particularly from senators who argued that the proposed bill did little to reduce borrowing or lower the cost of higher education. So despite the concerns of bankers and economists that the $1.1 trillion student loan debt is dampening the national economy, the bill was turned aside on June 11, 2014.

Which raises the matter of audiences, and we are left asking whether Senator Warren’s bill spoke equally well to students, parents, bankers, and members of Congress. Some of those audiences failed to be convinced.

Some proposals are tailored to general audiences; consequently, they avoid technical language, make straightforward and relatively simple points, and sometimes use charts, graphs, and tables to make data comprehensible. You can find such arguments, for example, in newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, and political documents like Senator Warren’s proposed legislation. And such appeals to a broad group make sense when a proposal — say, to finance new toll roads or build an art museum — must surf on waves of community support and financing.

But often proposals need to win the approval of specific groups or individuals (such as financiers, developers, public officials, and legislators) who have the power to make change actually happen. Such arguments will usually be more technical, detailed, and comprehensive than those aimed at the general public because people directly involved with an issue have a stake in it. They may be affected by it themselves and thus have in-depth knowledge of the subject. Or they may be responsible for implementing the proposal. You can expect them to have specific questions about it and, possibly, formidable objections. So identifying your potential audiences is critical to the success of any proposal. On your own campus, for example, a plan to alter admissions policies might be directed both to students in general and (perhaps in a different form) to the university president, members of the faculty council, and admissions officers.

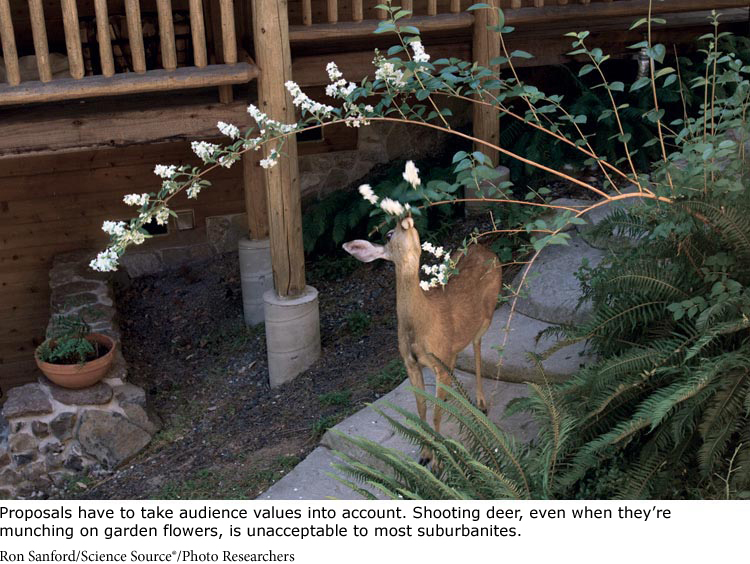

An effective proposal also has to be compatible with the values of the audience. Some ideas may make good sense but cannot be enacted. For example, many American towns and cities have a problem with expanding deer populations. Without natural predators, the deer are moving closer to homes, dining on gardens and shrubbery, and endangering traffic. Yet one obvious and feasible solution — culling the herds through hunting — is usually not saleable to communities (perhaps too many people remember Bambi).

RESPOND •

Work in a group to identify about half a dozen problems on your campus or in the local community, looking for a wide range of issues. (Don’t focus on problems in individual classes.) Once you have settled on these issues, then use various resources — the Web, the phone book (if you can find one), a campus directory — to locate specific people, groups, or offices whom you might address or influence to deal with the issues you have identified.