Developing Proposals

Developing Proposals

In developing a proposal, you will have to do some or all of the following:

Define a problem that needs a solution or describe a need that is not currently addressed.

Make a strong claim that addresses the problem or need. Your solution should be an action directed at the future.

Show why your proposal will fix the problem or address the need.

Demonstrate that your proposal is feasible.

This might sound easy, but writing a proposal argument can be a process of discovery. At the outset, you think you know exactly what ought to be done, but by the end, you may see (and even recommend) other options.

Defining a Need or Problem

To make a proposal, first establish that a need or problem exists. You’ll typically dramatize the problem that you intend to fix at the beginning of your project and then lead up to a specific claim. But in some cases, you could put the need or problem right after your claim as the major reason for adopting the proposal:

Let’s ban cell phones on campus now. Why? Because we’ve become a school of walking zombies. No one speaks to or even acknowledges the people they meet or pass on campus. Half of our students are so busy chattering to people that they don’t participate in the community around them.

How can you make readers care about the problem you hope to address? Following are some strategies:

Paint a vivid picture of the need or problem.

Show how the need or problem affects people, both those in the immediate audience and the general public as well.

Underscore why the need or problem is significant and pressing.

Explain why previous attempts to address the issue may have failed.

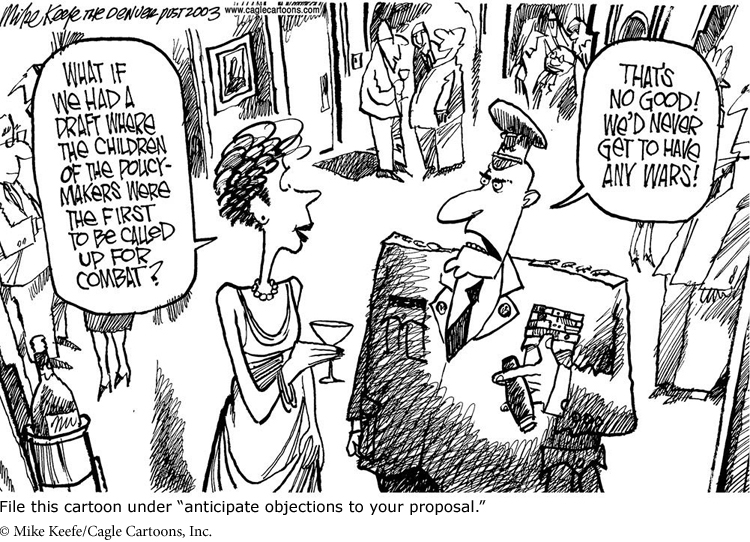

For example, in proposing that the military draft be restored in the United States or that all young men and women give two years to national service (a tough sell!), you might begin by drawing a picture of a younger generation that is self-absorbed, demands instant gratification, and doesn’t understand what it means to participate as a full member of society. Or you might note how many young people today fail to develop the life skills they need to strike out on their own. Or like congressional representative Charles Rangel (D-New York), who regularly proposes a Universal National Service Act, you could define the issue as a matter of fairness, arguing that the current all-volunteer army shifts the burden of national service to a small and unrepresentative sample of the American population. Speaking on CNN on January 26, 2013, Rangel said:

Since we replaced the compulsory military draft with an all-volunteer force in 1973, our nation has been making decisions about wars without worry over who fights them. I sincerely believe that reinstating the draft would compel the American public to have a stake in the wars we fight as a nation. That is why I wrote the Universal National Service Act, known as the “draft” bill, which requires all men and women between ages 18 and 25 to give two years of service in any capacity that promotes our national defense.

Of course, you would want to cite authorities and statistics to prove that any problem you’re diagnosing is real and that it touches your likely audience. Then readers may be ready to hear your proposal.

In describing a problem that your proposal argument intends to solve, be sure to review earlier attempts to fix it. Many issues have a long history that you can’t afford to ignore (or be ignorant of). Understand too that some problems seem to grow worse every time someone tinkers with them. You might pause before proposing any new attempt to reform the current system of financing federal election campaigns when you discover that previous reforms have resulted in more bureaucracy, more restrictions on political expression, and more unregulated money flowing into the system. “Enough is enough” can be a potent argument when faced with such a mess.

RESPOND •

If you review “Let’s Charge Politicians for Wasting Our Time” at the end of this chapter, a brief proposal by political and culture writer/blogger Virginia Postrel, you’ll see that she spends quite a bit of time pointing out the irritation caused by unwanted political robocalls to her landline, even though she recognizes that such calls are illegal on cell phones. Does this focus on the landline take away from her proposal that the politicians should have to pay a fee for such calls as well as for unsolicited email messages they send, a proposal also put forward by technology guru Esther Dyson? Would you advise her to revise her argument — and if so, how?

Making a Strong and Clear Claim

After you’ve described and analyzed a problem, you’re prepared to offer a fix. Begin with your claim (a proposal of what X or Y should do), followed by the reason(s) that X or Y should act and the effects of adopting the proposal:

| Claim | Communities should encourage the development of charter schools. |

| Reason | Charter schools are not burdened by the bureaucracy that is associated with most public schooling. |

| Effects | Instituting such schools will bring more effective education to communities and offer an incentive to the public schools to improve their programs. |

Having established a claim, you can explore its implications by drawing out the reasons, warrants, and evidence that can support it most effectively:

| Claim | In light of a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision that ruled that federal drug laws cannot be used to prosecute doctors who prescribe drugs for use in suicide, our state should immediately pass a bill legalizing physician-assisted suicide for patients who are terminally ill. |

| Reason | Physician-assisted suicide can relieve the suffering of those who are terminally ill and will die soon. |

| Warrant | The relief of suffering is desirable. |

| Evidence | Oregon voters have twice approved the state’s Death with Dignity Act, which has been in effect since 1997, and to date the suicide rate has not risen sharply, nor have doctors given out a large number of prescriptions for death-inducing drugs. Several other states are considering ballot initiatives in favor of doctor-assisted suicide. |

The reason sets up the need for the proposal, whereas the warrant and evidence demonstrate that the proposal is just and could meet its objective. Your actual argument would develop each point in detail.

RESPOND •

For each problem and solution below, make a list of readers’ likely objections to the solution offered. Then propose a solution of your own, and explain why you think it’s more workable than the original.

| Problem | Future deficits in the Social Security system |

| Solution | Raise the age of retirement to seventy-two. |

| Problem | Severe grade inflation in college courses |

| Solution | Require a prescribed distribution of grades in every class: 10% A; 20% B; 40% C; 20% D; 10% F. |

| Problem | Increasing rates of obesity in the general population |

| Solution | Ban the sale of high-fat sandwiches and entrees in fast-food restaurants. |

| Problem | Inattentive driving because drivers are texting |

| Solution | Institute a one-year mandatory prison sentence for the first offense. |

| Problem | Increase in sexual assaults on and around campus |

| Solution | Establish a 10:00 p.m. curfew on weekends. |

Showing That the Proposal Addresses the Need or Problem

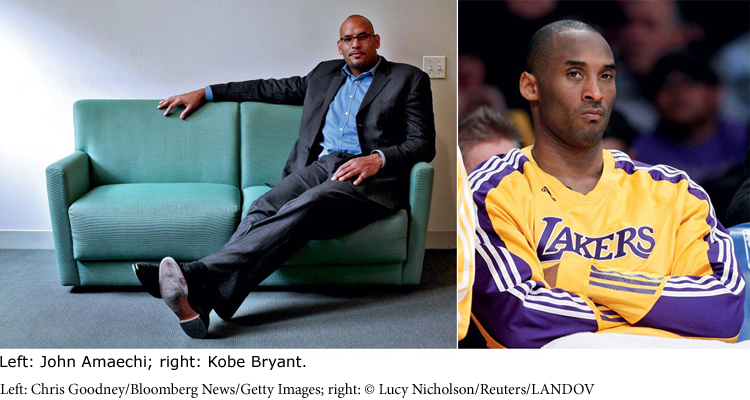

An important but tricky part of making a successful proposal lies in relating the claim to the need or problem that it addresses. Facts and probability are your best allies. Take the time to show precisely how your solution will fix a problem or at least improve upon the current situation. Sometimes an emotional appeal is fair play, too. Here’s former NBA player John Amaechi using that approach when he asks superstar Kobe Bryant of the L.A. Lakers not to appeal a $100,000 penalty he received for hurling an antigay slur at a referee:

Rose Eveleth explains how subtitled television and movies could help to preserve endangered languages in “Saving Languages through Korean Soap Operas.”

Kobe, stop fighting the fine. You spoke ill-advised words that shot out like bullets, and if the emails I received from straight and gay young people and sports fans in Los Angeles alone are anything to go by, you did serious damage with your outburst.

A young man from a Los Angeles public school emailed me. You are his idol. He is playing up, on the varsity team, he has your posters all over his room, and he hopes one day to play in college and then in the NBA with you. He used to fall asleep with images of passing you the ball to sink a game-winning shot. He watched every game you played this season on television, but this week he feels less safe and less positive about himself because he stared adoringly into your face as you said the word that haunts him in school every single day.

Kobe, stop fighting the fine. Use that money and your influence to set a new tone that tells sports fans, boys, men, and the society that looks up to you that the word you said in anger is not OK, not ever. Too many athletes take the trappings of their hard-earned success and leave no tangible legacy apart from “that shot” or “that special game.”

— John Amaechi, “A Gay Former NBA Player Responds to Kobe Bryant”

Kobe Bryant

The paragraph describing the reaction of the schoolboy provides just the tie that Amaechi needs between his proposal and the problem it would address. The story also gives his argument more power.

Alternatively, if you oppose an idea, these strategies work just as well in reverse: if a proposal doesn’t fix a problem, you have to show exactly why. Here are a few paragraphs from an editorial posting by Doug Bandow for Forbes in which he refutes a proposal for reinstating military conscription:

All told, shifting to conscription would significantly weaken the military. New “accessions,” as the military calls them, would be less bright, less well educated, and less positively motivated. They would be less likely to stay in uniform, resulting in a less experienced force. The armed forces would be less effective in combat, thereby costing America more lives while achieving fewer foreign policy objectives.

Why take such a step?

One argument, most recently articulated by Thomas Ricks of the Center for a New American Security, is that a draft would save “the government money.” That’s a poor reason to impress people into service.

First, conscription doesn’t save much cash. It costs money to manage and enforce a draft — history demonstrates that not every inductee would go quietly. Conscripts serve shorter terms and reenlist less frequently, increasing turnover, which is expensive. And unless the government instituted a Czarist lifetime draft, everyone beyond the first ranks would continue to expect to be paid.

Second, conscription shifts rather than reduces costs. Ricks suggested that draftees should “perform tasks currently outsourced at great cost to the Pentagon: paperwork, painting barracks, mowing lawns, driving generals around.” Better to make people do grunt work than to pay them to do it? Force poorer young people into uniform in order to save richer old people tax dollars. Ricks believes that is a good reason to jail people for refusing to do as the government demands?

The government could save money in the same way by drafting FBI agents, postal workers, Medicare doctors, and congressmen. Nothing warrants letting old politicians force young adults to pay for Washington’s profligacy. Moreover, by keeping some people who want to serve out while forcing others who don’t want to serve in — creating a veritable evasion industry along the way — conscription would raise total social costs. It would be a bad bargain by any measure.

— Doug Bandow, “A New Military Draft Would Revive a Very Bad Old Idea”

Finally, if your own experience backs up your claim or demonstrates the need or problem that your proposal aims to address, then consider using it to develop your proposal (as John Amaechi does in addressing his proposal to Kobe Bryant). Consider the following questions in deciding when to include your own experiences in showing that a proposal is needed or will in fact do what it claims:

Is your experience directly related to the need or problem that you seek to address or to your proposal about it?

Will your experience be appropriate and speak convincingly to the audience? Will the audience immediately understand its significance, or will it require explanation?

Does your personal experience fit logically with the other reasons that you’re using to support your claim?

Be careful. If a proposal seems crafted to serve mainly your own interests, you won’t get far.

Showing That the Proposal Is Feasible

To be effective, proposals must be feasible — that is, the action proposed can be carried out in a reasonable way. Demonstrating feasibility calls on you to present evidence — from similar cases, from personal experience, from observational data, from interview or survey data, from Internet research, or from any other sources — showing that what you propose can indeed be done with the resources available. “Resources available” is key: if the proposal calls for funds, personnel, or skills beyond reach or reason, your audience is unlikely to accept it. When that’s the case, it’s time to reassess your proposal, modify it, and test any new ideas against these revised criteria. This is also when you can reconsider proposals that others might suggest are better, more effective, or more workable than yours. There’s no shame in admitting that you may have been wrong. When drafting a proposal, ask friends to think of counterproposals. If your own proposal can stand up to such challenges, it’s likely a strong one.

Considering Design and Visuals

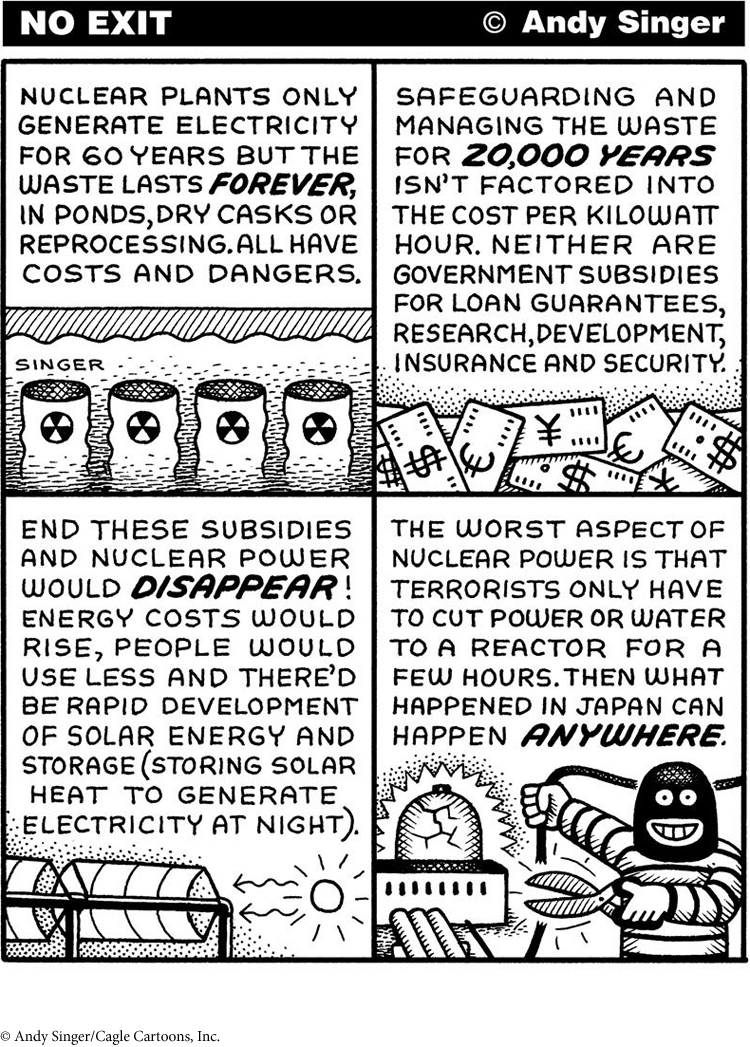

Because proposals often address specific audiences, they can take a number of forms — a letter, a memo, a Web page, a feasibility report, an infographic, a brochure, a prospectus, or even an editorial cartoon (see Andy Singer’s “No Exit” item in “Making a Strong and Clear Claim”). Each form has different design requirements. Indeed, the design may add powerfully to — or detract significantly from — the effectiveness of the proposal. Typically, though, proposals are heavy in photographs, tables, graphs, comparison charts, and maps, all designed to help readers understand the nature of a problem and how to solve it. Needless to say, any visual items should be handsomely presented: they contribute to your ethos.

Lengthy reports also usually need headings — or, in an oral report, slides — that clearly identify the various stages of the presentation. Those headings, which will vary, would include items such as Introduction, Nature of the Problem, Current Approaches or Previous Solutions, Proposal/Recommendations, Advantages, Counterarguments, Feasibility, Implementation, and so on. So before you produce a final copy of any proposal, be sure its design enhances its persuasiveness.

A related issue to consider is whether a graphic image might help readers understand key elements of the proposal — what the challenge is, why it demands action, and what exactly you’re suggesting — and help make the idea more attractive. That strategy is routinely used in professional proposals by architects, engineers, and government agencies.

For example, the artist rendering below shows the Bionic Arch, a proposed skyscraper in Taiwan designed by architect Vincent Callebaut. As a proposal, this one stands out because it not only suggests an addition to the city skyline, but it also offers architectural innovations to make the structure more environmentally friendly. If you look closely, you’ll notice that each floor of the building includes suspended “sky gardens” that, according to the proposal, will help solve the problem of city smog by siphoning away toxic fumes. According to Callebaut, “The skyscraper reduces our ecological footprint in the urban area. It respects the environment and gives a new symbiotic ecosystem for the biodiversity of Taiwan. The Bionic Arch is the new icon of sustainable development.”