Punctuation and Argument

Punctuation and Argument

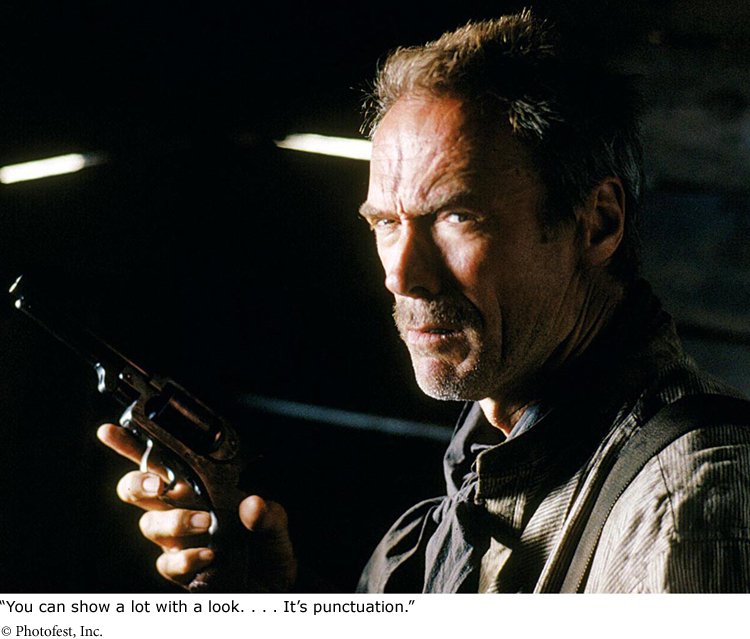

In a memorable comment, actor and director Clint Eastwood said, “You can show a lot with a look. . . . It’s punctuation.” He’s certainly right about punctuation’s effect, and it is important that as you read and write arguments, you consider punctuation closely.

Eastwood may have been talking about the dramatic effect of end punctuation: the finality of periods; the tentativeness of ellipses (. . .); the query, disbelief, or uncertainty in question marks; or the jolt in the now-appearing-almost-everywhere exclamation point! Yet even exclamations can help create tone if used strategically. In an argument about the treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo, consider how Jane Mayer evokes the sense of desperation in some of the suspected terrorists:

As we reached the end of the cell-block, hysterical shouts, in broken English, erupted from a caged exercise area nearby. “Come here!” a man screamed. “See here! They are liars! . . . No sleep!” he yelled. “No food! No medicine! No doctor! Everybody sick here!”

— Jane Mayer, “The Experiment”

Punctuation that works within sentences can also do much to enhance meaning and style. The semicolon, for instance, marks a pause that is stronger than a comma but not as strong as a period. Semicolons function like “plus signs”; used correctly, they join items that are alike in structure, conveying a sense of balance, similarity, or even contrast. Do you recall Nathaniel Stein’s parody of grading standards at Harvard University (see “Looking at Style” in Chapter 6, “Rhetorical Analysis”)? Watch as he uses a semicolon to enhance the humor in his description of what an A+ paper achieves:

Nearly every single word in the paper is spelled correctly; those that are not can be reasoned out phonetically within minutes.

— Nathaniel Stein, “Leaked! Harvard’s Grading Rubric”

In many situations, however, semicolons, with their emphasis on symmetry and balance, can feel stodgy, formal, and maybe even old-fashioned, and lots of writers avoid them, perhaps because they are very difficult to get right. Check a writing handbook before you get too friendly with semicolons.

Much easier to manage are colons, which function like pointers within sentences: they say pay attention to this. Philip Womack’s London Telegraph review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 demonstrates how a colon enables a writer to introduce a lengthy illustration clearly and elegantly:

The first scene of David Yates’s film picks up where his previous installment left off: with a shot of the dark lord Voldemort’s noseless face in triumph as he steals the most powerful magic wand in the world from the tomb of Harry’s protector, Professor Dumbledore.

— Philip Womack

And Paul Krugman shows how to use a colon to catch a reader’s attention:

Recently two research teams, working independently and using different methods, reached an alarming conclusion: The West Antarctic ice sheet is doomed.

— Paul Krugman, “Point of No Return”

Colons can serve as lead-ins for complete sentences, complex phrases, or even single words. As such, they are versatile and potentially dramatic pieces of punctuation.

Like colons, dashes help readers focus on important, sometimes additional details. But they have even greater flexibility since they can be used singly or in pairs. Alone, dashes function much like colons to add information. Here’s Eugene Washington commenting pessimistically on a political situation in Iraq, using a single dash to extend his thoughts:

The aim of U.S. policy at this point should be minimizing the calamity, not chasing rainbows of a unified, democratic, pluralistic Iraq — which, sadly, is something the power brokers in Iraq do not want.

— Eugene Robinson, “The ‘Ungrateful Volcano’ of Iraq”

And here are paired dashes used to insert such information in the opening of the Philip Womack review of Deathly Hallows 2 cited earlier:

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 — the eighth and final film in the blockbusting series — begins with our teenage heroes fighting for their lives, and for their entire world.

And finally, notice how in an essay about President Obama’s second term, writer Peggy Noonan surrounds a single word with dashes to emphasize it:

All this is weird, unprecedented. The president shows no sign — none — of being overwhelmingly concerned and anxious at his predicaments or challenges.

— Peggy Noonan, “The Daydream and the Nightmare”

As these examples illustrate, punctuation often enhances the rhythm of an argument. Take a look at how Maya Angelou uses a dash along with another punctuation mark — ellipsis points — to create a pause or hesitation, in this case one that builds anticipation:

Then the voice, husky and familiar, came to wash over us — “The winnah, and still heavyweight champeen of the world . . . Joe Louis.”

— Maya Angelou, “Champion of the World”

RESPOND •

Try writing a brief movie review for your campus newspaper, experimenting with punctuation as one way to create an effective style. See if using a series of questions might have a strong effect, whether exclamation points would add or detract from the message you want to send, and so on. When you’ve finished the review, compare it to one written by a classmate, and look for similarities and differences in your choices of punctuation.