Special Effects: Figurative Language

Special Effects: Figurative Language

You don’t have to look hard to find examples of figurative language adding style to arguments. When a writing teacher suggests you take a weed whacker to your prose, she’s using a figure of speech (in this case, a metaphor) to suggest you cut the wordiness. To indicate how little he trusts the testimony of John Koskinen, head of the Internal Revenue Service, political pundit Michael Gerson takes the metaphor of a “witch hunt” and flips it on the bureaucrat, relying on readers to recognize an allusion to Shakespeare’s Macbeth:

Explore the meaning and effectiveness of figurative expressions such as “Gourmet Hay” and “‘trail mix’ for earthworms” in Eric Mortenson’s “A Diversified Farm Prospers in Oregon’s Willamette Valley by Going Organic and Staying Local.”

Democrats were left to complain about a Republican “witch hunt” — while Koskinen set up a caldron, added some eye of newt and toe of frog and hailed the Thane of Cawdor.

— Michael Gerson, “An Arrogant and Lawless IRS”

Figurative language like this — indispensable to writers — dramatizes ideas, either by clarifying or enhancing the thoughts themselves or by framing them in language that makes them stand out. As a result, figurative language makes arguments attractive, memorable, and powerful. An apt simile, a timely rhetorical question, or a wicked understatement might do a better job bringing an argument home than whole paragraphs of evidence.

Figures of speech are usually classified into two main types: tropes, which involve a change in the ordinary meaning of a word or phrase; and schemes, which involve a special arrangement of words. Here is a brief alphabetical listing — with examples — of some of the most familiar kinds.

Tropes

To create tropes, you often have to think of one idea or claim in relationship to others. Some of the most powerful — one might even say inevitable — tropes involve making purposeful comparisons between ideas: analogies, metaphors, and similes. Other tropes such as irony, signifying, and understatement are tools for expressing attitudes toward ideas: you might use them to shape the way you want your audience to think about a claim that you or someone else has made.

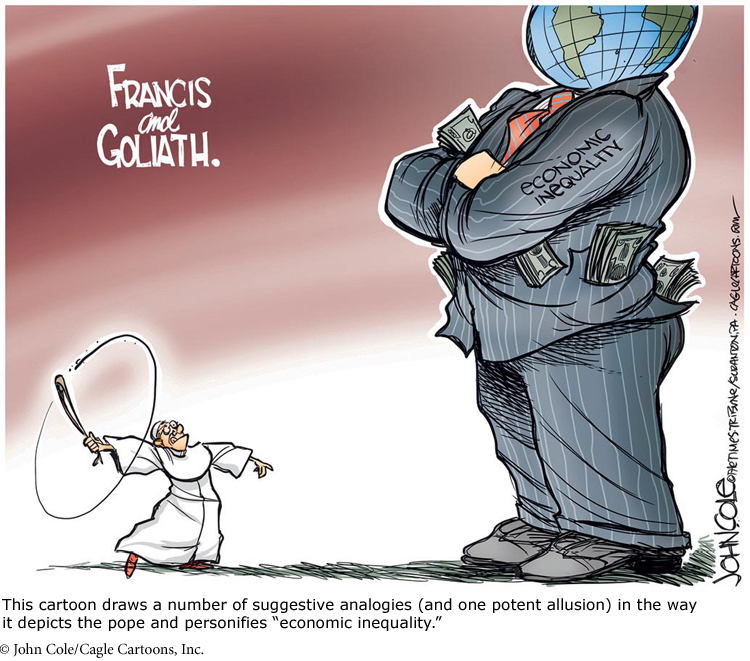

Allusion

An allusion is a connection that illuminates one situation by comparing it to another similar but usually more famous one, often with historical or literary connections. Allusions work with events, people, or concepts — expanding and enlarging them so readers better appreciate their significance. For example, a person who makes a career-ending blunder might be said to have met her Waterloo, the famous battle that terminated Napoleon’s ambitions. Similarly, every impropriety in Washington brings up mentions of Watergate, the only scandal to lead to a presidential resignation; any daring venture becomes a moon shot, paralleling the ambitious program that led to a lunar landing in 1969. Using allusions can be tricky: they work only if readers get the connection. But when they do, they can pack a wallop. When Michael Gerson, above, mentions “eye of newt” and “toe of frog” in the same breath as IRS chief John Koskinen, he knows what fans of Macbeth are thinking. But other readers might be left clueless.

Analogy

Analogies compare two things, often point by point, either to show similarity or to suggest that if two concepts, phenomena, events, or even people are alike in one way, they are probably alike in other ways as well. Often extended in length, analogies can clarify or emphasize points of comparison, thereby supporting particular claims.

Here’s the first paragraph of an essay in which a writer who is also a runner thinks deeply about the analogies between the two tough activities:

When people ask me what running and writing have in common, I tend to look at the ground and say it might have something to do with discipline: You do both of those things when you don’t feel like it, and make them part of your regular routine. You know some days will be harder than others, and on some you won’t hit your mark and will want to quit. But you don’t. You force yourself into a practice; the practice becomes habit and then simply part of your identity. A surprising amount of success, as Woody Allen once said, comes from just showing up.

— Rachel Toor, “What Writing and Running Have in Common”

To be effective, an analogy has to make a good point and hold up to scrutiny. If it doesn’t, it can be criticized as a faulty analogy, a fallacy of argument (see “Faulty Analogy” in Chapter 5, “Fallacies of Argument”).

Antonomasia

Antonomasia is an intriguing trope that simply involves substituting a descriptive phrase for a proper name. It is probably most familiar to you from sports or entertainment figures: “His Airness” still means Michael Jordan; Aretha Franklin remains “The Queen of Soul,” jazz singer Mel Torme was “The Velvet Fog,” and Superman, of course, is “The Man of Steel.” In politics, antonomasia is sometimes used neutrally (Ronald Reagan as “The Gipper”), sometimes as a backhanded compliment (Margaret Thatcher as “The Iron Lady”), and occasionally as a crude and sexist put-down (Sarah Palin as “Caribou Barbie”). As you well know if you have one, nicknames can pack potent arguments into just one phrase.

Hyperbole

Hyperbole is the use of overstatement for special effect, a kind of fireworks in prose. The tabloid gossip magazines that scream at you in the checkout line survive by hyperbole. Everyone has seen these overstated arguments and perhaps marveled at the way they sell.

Hyperbole can, however, serve both writers and audiences when very strong opinions need to be registered. One senses exasperation in the no-holds-barred opening of Rex Reed’s review of the film Tammy — the paragraph ripples with hyperbole and other tropes:

The good news is that Tammy is not a crappy remake of the 1957 Tammy movie with Debbie Reynolds that spawned three sequels and a TV comedy series. The bad news is that this one is much worse. It’s a desperate and brainless vehicle for Melissa McCarthy, which she wrote herself, with her husband, Ben Falcone, who also directed, with all the efficiency and verve of an abandoned Volkswagen on the Jersey Turnpike. There isn’t a single shred of evidence that either of them has one iota of talent in the world of filmmaking. Tammy is not just a celebration of everything vulgar and stupid in the dumbing down of American movies. It’s a rambling, pointless and labored attempt to cash in on Ms. McCarthy’s fan base without respect for any audience with a collective IQ of 10. And it’s about as funny as a liver transplant.

— Rex Reed, “Melissa McCarthy Gives ‘Tammy’ Her All, but It’s Nowhere Near Enough”

Can you tell that Reed did not like the film?

Irony

Irony is a complex trope in which words convey meanings that are in tension with or even opposite to their literal meanings. Readers who catch the irony realize that a writer is asking them (or someone else) to think about all the potential connotations in their language. One of the most famous uses of satiric irony in literature occurs in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar when Antony punctuates his condemnation of Caesar’s assassins with the repeated word “honourable.” He begins by admitting, “So are they all, honourable men” but ends railing against “the honourable men / Whose daggers have stabb’d Caesar.” Within just a few lines, Antony’s funeral speech has altered the meaning of the term.

In popular culture, irony often takes a humorous bent in publications such as the Onion and the appropriately named Ironic Times. Yet even serious critics of society and politics use satiric devices to undercut celebrities and politicians, particularly when such powerful figures ignore the irony in their own positions. After Hillary Clinton argued that Americans don’t regard her and her husband as part of the country’s problem with income inequality “because we pay ordinary income tax . . . and we’ve done it through dint of hard work,” Washington Post columnist and fellow liberal Ruth Marcus offered advice rich in sarcasm and irony:

And for goodness’ sake — truly well-off? hard work? You are truly well-off by anyone’s definition of the term. And hard work is the guys tearing up my roof right now. It’s not flying by private jet to pick up a check for $200,000 to stand at a podium for an hour. . . .

— Ruth Marcus, “Hillary Clinton’s Money Woes”

Metaphor

A bedrock of our language, metaphor creates or implies a comparison between two things, illuminating something unfamiliar by correlating it to something we usually know much better. For example, to explain the complicated structure of DNA, scientists Watson and Crick famously used items people would likely recognize: a helix (spiral) and a zipper. Metaphors can clarify and enliven arguments. In the following passage, novelist and poet Benjamin Sáenz uses several metaphors (highlighted) to describe his relationship to the southern border of the United States:

It seems obvious to me now that I remained always a son of the border, a boy never quite comfortable in an American skin, and certainly not comfortable in a Mexican one. My entire life, I have lived in a liminal space, and that space has both defined and confined me. That liminal space wrote and invented me. It has been my prison, and it has also been my only piece of sky.

— Benjamin Sáenz, “Notes from Another Country”

In another example from Andrew Sullivan’s blog, he quotes an 1896 issue of Munsey’s Magazine that uses a metaphor to explain what, at that time, the bicycle meant to women and to clarify the new freedom it gave women who weren’t accustomed to being able to ride around on their own:

To men, the bicycle in the beginning was merely a new toy, another machine added to the long list of devices they knew in their work and play. To women, it was a steed upon which they rode into a new world.

Metonymy

Metonymy is a rhetorical trope in which a writer uses a particular object to stand for a general concept. You’ll recognize the move immediately in the expression “The pen is mightier than the sword” — which obviously is not about Bics and sabers. Metonyms are vivid and concrete ways of compacting big concepts into expressive packages for argument: the term Wall Street can embody the nation’s whole complicated banking and investment system, while all the offices and officials of the U.S. military become the Pentagon. You can quickly think of dozens of expressions that represent larger, more complex concepts: Nashville, Hollywood, Big Oil, the Press, the Oval Office, even perhaps the electorate.

Oxymoron

Oxymoron is a rhetorical trope that states a paradox or contradiction. John Milton created a classic example when he described Hell as a place of “darkness visible.” We may be less poetic today, but we nevertheless appreciate the creativity (or arrogance) in expressions such as light beer, sports utility vehicle, expressway gridlock, or negative economic growth. You might not have much cause to use this figure in your writing, but you’ll get credit for noting and commenting on oxymoronic ideas or behaviors.

Rhetorical Question

Rhetorical questions, which we use frequently, are questions posed by a speaker or writer that don’t really require answers. Instead, an answer is implied or unimportant. When you say “Who cares?” or “What difference does it make?” you’re using such questions.

Rhetorical questions show up in arguments for many reasons, most often perhaps to direct readers’ attention to the issues a writer intends to explore. For example, Erin Biba asks a provocative, open-ended rhetorical question in her analysis of Facebook “friending”:

So if we’re spending most of our time online talking to people we don’t even know, how deep can the conversation ever get?

— Erin Biba, “Friendship Has Its Limits”

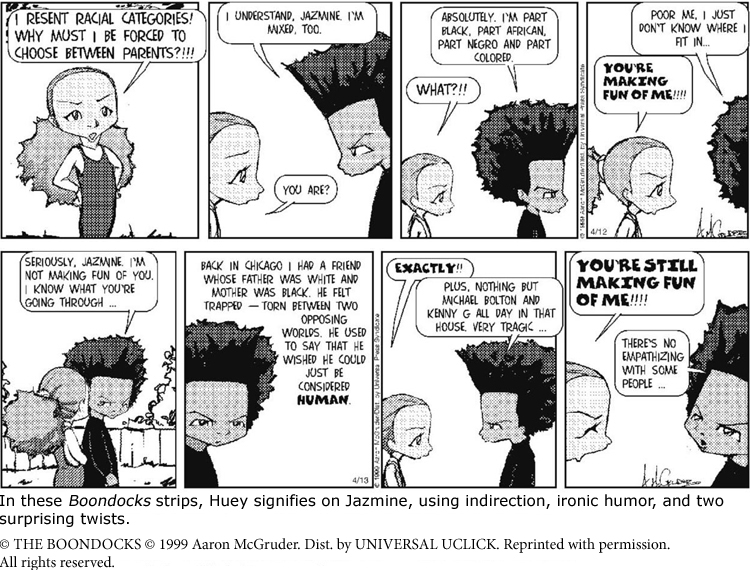

Signifying

Signifying, in which a speaker or writer cleverly and often humorously needles another person, is a distinctive trope found extensively in African American English. In the following passage, two African American men (Grave Digger and Coffin Ed) signify on their white supervisor (Anderson), who has ordered them to discover the originators of a riot:

“I take it you’ve discovered who started the riot,” Anderson said.

“We knew who he was all along,” Grave Digger said.

“It’s just nothing we can do to him,” Coffin Ed echoed.

“Why not, for God’s sake?”

“He’s dead,” Coffin Ed said.

“Who?”

“Lincoln,” Grave Digger said.

“He hadn’t ought to have freed us if he didn’t want to make provisions to feed us,” Coffin Ed said. “Anyone could have told him that.”

— Chester Himes, Hot Day, Hot Night

Coffin Ed and Grave Digger demonstrate the major characteristics of effective signifying — indirection, ironic humor, fluid rhythm, and a surprising twist at the end. Rather than insulting Anderson directly by pointing out that he’s asked a dumb question, they criticize the question indirectly by ultimately blaming a white man for the riot (and not just any white man, but one they’re supposed to revere). This twist leaves the supervisor speechless, teaching him something and giving Grave Digger and Coffin Ed the last word — and last laugh.

Take a look at the example of signifying from a Boondocks cartoon (see below). Note how Huey seems to be sympathizing with Jazmine and then, in two surprising twists, reveals that he has been needling her all along.

Simile

A simile uses like or as to compare two things. Here’s a simile from an essay on cosmology from the New York Times:

Through his general theory of relativity, Einstein found that space, and time too, can bend, twist, and warp, responding much as a trampoline does to a jumping child.

— Brian Greene, “Darkness on the Edge of the Universe”

And here is a series of similes, from an excerpt of a Wired magazine review of a new magazine for women:

Women’s magazines occupy a special niche in the cluttered infoscape of modern media. Ask any Vogue junkie: no girl-themed Web site or CNN segment on women’s health can replace the guilty pleasure of slipping a glossy fashion rag into your shopping cart. Smooth as a pint of chocolate Häagen-Dazs, feckless as a thousand-dollar slip dress, women’s magazines wrap culture, trends, health, and trash in a single, decadent package. But like the diet dessert recipes they print, these slick publications can leave a bad taste in your mouth.

— Tiffany Lee Brown, “En Vogue”

Here, three similes — smooth as a pint of chocolate Häagen-Dazs and feckless as a thousand-dollar slip dress in the third sentence, and like the diet dessert recipes in the fourth — add to the image of women’s magazines as a mishmash of “trash” and “trends.”

Understatement

Understatement uses a quiet message to make its point. In her memoir, Rosa Parks — the civil rights activist who made history in 1955 by refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger — uses understatement so often that it becomes a hallmark of her style. She refers to her lifelong efforts to advance civil rights as just a small way of “carrying on.”

Understatement can be particularly effective in arguments that might seem to call for its opposite. Outraged that New York’s Metropolitan Opera has decided to stage The Death of Klinghoffer, a work depicting the murder by terrorists of a wheelchair-bound Jewish passenger on a cruise ship in 1985, writer Eve Epstein in particular points to an aria in which a terrorist named Rambo blames all the world’s problems on Jews, and then, following an evocative dash, she makes a quiet observation:

Rambo’s aria echoes the views of Der Stürmer, Julius Streicher’s Nazi newspaper, without a hint of irony or condemnation. The leitmotif of the morally and physically crippled Jew who should be disposed of has been heard before — and it did not end well.

— Eve Epstein, “The Met’s Staging of Klinghoffer Should Be Scrapped”

“It did not end well” alludes, of course, to the Holocaust.

RESPOND •

Use online sources (such as American Rhetoric’s Top 100 Speeches at americanrhetoric.com/top100speechesall.html) to find the text of an essay or a speech by someone who uses figures of speech liberally. Pick a paragraph that is rich in figures and rewrite it, eliminating every bit of figurative language. Then read the original and your revised version aloud to your class. Can you imagine a rhetorical situation in which your pared-down version would be more appropriate?

Schemes

Schemes are rhetorical figures that manipulate the actual word order of phrases, sentences, or paragraphs to achieve specific affects, adding stylistic power or “zing” to arguments. The variety of such devices is beyond the scope of this work. Following are schemes that you’re likely to see most often, again in alphabetical order.

Anaphora

Anaphora, or effective repetition, can act like a drumbeat in an argument, bringing the point home. Sometimes an anaphora can be quite obvious, especially when the repeated expressions occur at the beginning of a series of sentences or clauses. Here is President Lyndon Johnson urging Congress in 1965 to pass voting rights legislation:

There is no constitutional issue here. The command of the Constitution is plain.

There is no moral issue. It is wrong — deadly wrong — to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country.

There is no issue of States rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights.

I have not the slightest doubt what will be your answer.

Repetitions can occur within sentences or paragraphs as well. Here, in an argument about the future of Chicago, Lerone Bennett Jr. uses repetition to link Chicago to innovation and creativity:

[Chicago]’s the place where organized Black history was born, where gospel music was born, where jazz and the blues were reborn, where the Beatles and the Rolling Stones went up to the mountaintop to get the new musical commandments from Chuck Berry and the rock’n’roll apostles. — Lerone Bennett Jr. “Blacks in Chicago”

Antithesis

Antithesis is the use of parallel words or sentence structures to highlight contrasts or opposition:

Marriage has many pains, but celibacy has no pleasures.

— Samuel Johnson

Those who kill people are called murderers; those who kill animals, sportsmen.

Inverted Word Order

Inverted word order is a comparatively rare scheme in which the parts of a sentence or clause are not in the usual subject-verb-object order. It can help make arguments particularly memorable:

Into this grey lake plopped the thought, I know this man, don’t I?

— Doris Lessing

Hard to see, the dark side is. — Yoda

Parallelism

Parallelism involves the use of grammatically similar phrases or clauses for special effect. Among the most common of rhetorical effects, parallelism can be used to underscore the relationships between ideas in phrases, clauses, complete sentences, or even paragraphs. You probably recognize the famous parallel clauses that open Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times,

it was the worst of times . . .

The author’s paralleled clauses and sentences go on and on through more than a half-dozen pairings, their rhythm unforgettable. Or consider how this unattributed line from the 2008 presidential campaign season resonates because of its elaborate and sequential parallel structure:

Rosa sat so that Martin could walk. Martin walked so that Obama could run. Obama ran so that our children could fly.

RESPOND •

Identify the figurative language used in the following slogans. Note that some slogans may use more than one device.

“A day without orange juice is like a day without sunshine.” (Florida Orange Juice)

“Open happiness.” (Coca-Cola)

“Be all that you can be.” (U.S. Army)

“Breakfast of champions.” (Wheaties)

“America runs on Dunkin’.” (Dunkin’ Donuts)

“Like a rock.” (Chevrolet trucks)