Preparing a Presentation

Preparing a Presentation

Sooner or later, you’ll be asked to deliver a presentation in a college class. That’s because the ability to explain material clearly to an audience is a skill much admired by potential employers. Unfortunately, instructors sometimes give little practical advice about how to hone that talent, which is not a natural gift for most people. While it’s hard to generalize here, capable presenters attribute their success to the following strategies and perceptions:

They make sure they know their subjects thoroughly.

They pay attention to the values, ideas, and needs of their listeners.

They use patterns and styles that make their spoken arguments easy to follow.

They realize that oral arguments are interactive. (Live audiences can argue back!)

They appreciate that most oral presentations involve visuals, and they plan accordingly. (We’ll address multimedia presentations in the next chapter.)

They practice, practice — and then practice some more.

We suggest a few additional moves for when you are specifically required to make a formal argument or presentation in class (or on the job): assess the rhetorical situation you face, nail down the details of the presentation, fashion a script or plan, choose media to fit your subject, and then deliver a good show.

Assess the Rhetorical Situation

Whether asked to make a formal oral report in class, to speak to the general public, or to join a panel discussion, ask yourself the same questions about rhetorical choices that you face whenever you make an argument.

Understanding Purpose. Figure out the major purpose of the assignment or situation. Is it to inform and enlighten your audience? To convince or persuade them? To explore a concept or principle? To stimulate discussion? To encourage a decision? Something else? Very important in school, will you be speaking to share your expertise or to prove that you have it (as you might in a class report)?

Assessing the Audience. Determine who will be listening to your talk. Just an instructor and classmates? Interested observers at a public meeting? People who know more about the subject than you do — or less? Or will you be a peer of the audience members — typically, a classmate? What mix of age groups, of gender, of political affiliation, of rank, etc., will be in the group? What expectations will listeners bring to the talk, and what opinions are they likely to hold? Will this audience be invited to ask questions after the event?

Compare the Supreme Court ruling in Chapter 27 to the cartoons in the same chapter. Consider how audience has shaped the way these pieces address a similar topic.

Deciding on Content. What exactly is the topic for the presentation? What is its general scope? Are you expected to make a narrow and specific argument drawn from a research assignment? Are you expected to argue facts, definitions, causes and effects? Will you be offering an evaluation or perhaps a proposal? What degree of detail is necessary, and how much evidence should you provide for your claims?

Choosing Structure and Style. Will your instructor or audience expect a specific type of report? What “parts” must your presentation include: introduction, background information, thesis, evidence, refutation, discussion, conclusion? Can you model the talk after other reports you have heard or public events you have attended? Can you modify a conventional presentation to suit your topic better? Will the audience expect a serious presentation in academic style or can you be friendly and colloquial, perhaps even funny? Crucially, by what standards is your report likely to be assessed or graded?

Following are three excerpts from a detailed, three-page outline that sophomore George Chidiac worked up on his own to prepare for a fifteen-minute oral report on Thomas More’s “Petition for Free Speech” (1523) — an important document on the path to establishing free speech as a natural right. Chidiac’s outline of rhetorical issues and concerns prepped him well enough to deliver the entire report without notes. His thesis is highlighted, but also notice the question Chidiac asks at the very end: So what? He recognizes an obligation to explain why his report should matter to his audience.

Oral Report Outline

Requirements:

10 minutes

Share what I’ve learned in my research

Help colleagues appreciate the research I’ve done

Introduction

Introduce myself

Agenda — subject of presentation

Define free speech: the right to express any opinions without censorship or restraint

Set the stage and present a dilemma

Stage: From history of free speech, we are going to micro-focus to Renaissance, to 16th-century England, to April 18, 1523, in the House of Commons where I want to share insight on a pivotal point in the advancement of free speech in a political context.

Dilemma: The king called all his advisers and those able to enact legislation to raise funds to go to war. You are the intermediary between the main legislative body and the king. You have three obligations: one to truth, one to the king, and one to the body you’re representing. The king wants money, the legislative body cannot object, and you want truth and the best outcome to win out. How do you reconcile this?

What

What’s my message? What’s the focal point of my presentation?

I want to provide a snapshot in time of the evolution of free speech.

Thomas More, in his Petition for Free Speech, incrementally advanced free speech as a duty and a right.

Who

Who made this happen? Who was involved?

Thomas More

Brief bio: Before he became Speaker → Chancellor of England, friend of King Henry VIII, theologian, poet, father

Henry VIII

William Roper (minor role)

Brief bio: son-in-law and chief biographer

* * *

Why

Why was More’s Petition “successful”? Why did Henry VIII accept the petition?

Henry VIII’s character

Humanist — or wished to subscribe to humanist principles

Resembled More

Rediscovery and reevaluation of classical civilization and application into modern intellectual and social culture

Spirit of amicitia — friendship with counsel — constancy, mutual loyalty, and concern for justice where the crux was “freedom of speech”

Parliamentary expectations

Relationship between king and Parliament

Still a matter of license, not true freedom — sufferance

Members of Parliament acting in goodwill

By accepting the petition, Henry acknowledged that while not all parliamentary speech should be permitted, not all speech critical of monarchy is slanderous

Oncoming war

* * *

SO WHAT?

What do I want my colleagues to take with them? Big lesson?

Freedom of speech we have today wasn’t always enjoyed.

“A Campus More Colorful than Reality: Beware That College Brochure” is a transcript of Deena Prichep’s interview on NPR. The NPR Web site (and this textbook) contain a picture of the controversial campus brochure, but those listening on the radio would not have had this visual reference.

Nail Down the Specific Details

Big-picture rhetorical considerations are obviously important in an oral report, but so are the details. Pay attention to exactly how much time you have to prepare for an event, a lecture, or a panel session, and how long the actual presentation should be: never infringe on the time of other speakers. Determine what visual aids, slides, or handouts might make the presentation successful. Will you need an overhead projector, a flip chart, a whiteboard? Decide whether presentation software, such as PowerPoint, Keynote, or Prezi, will help you make a stronger report. Then figure out where to acquire the equipment as well as the expertise to use it. If you run into problems, especially with classroom reports, consider low-tech alternatives. Sometimes, speaking clearly or sharing effective handouts works better than a plodding slideshow.

If possible, check out where your presentation will take place. In a classroom with fixed chairs? A lecture or assembly hall? An informal sitting area? Will you have a lectern? Other equipment? Will you sit or stand? Remain in one place or move around? What will the lighting be, and can you adjust it? Take nothing for granted, and if you plan to use media equipment, be ready with a backup strategy if a projector bulb dies or a Web site won’t load.

Not infrequently, oral presentations are group efforts. When that’s the case, plan and practice accordingly. The work should be divvied up according to the strengths of the participants: you will need to work out who speaks when, who handles the equipment, who takes the questions, and so on.

Fashion a Script Designed to Be Heard by an Audience

Unless you are presenting a formal lecture (pretty rare in college), most oral presentations are delivered from notes. But even if you do deliver a live presentation from a printed text, be sure to compose a script that is designed to be heard rather than read. Such a text — whether in the form of note cards, an overhead list, or a fully written-out paper — should feature a strong introduction and conclusion, an unambiguous structure with helpful transitions and signposts, concrete diction, and straightforward syntax.

Strong Introductions and Conclusions. Like readers, listeners remember beginnings and endings best. Work hard, therefore, to make these elements of your spoken argument memorable and personable. Consider including a provocative or puzzling statement, opinion, or question; a memorable anecdote; a powerful quotation; or a strong visual image. If you can connect your report directly to the interests or experiences of your listeners in the introduction or conclusion, then do so.

Be sure that your introduction clearly explains what your presentation will cover, what your focus will be, and perhaps even how the presentation will be arranged. Give listeners a mental map of where you are taking them. If you are using presentation software, a bare-bones outline sometimes makes sense, especially when the argument is a straightforward academic presentation: thesis + evidence.

The conclusion should drive home and reinforce your main point. You can summarize the key arguments you have made (again, a simple slide could do some of the work), but you don’t want to end with just a rehash, especially when the presentation is short. Instead, conclude by underscoring the implications of your report: what do you want your audience to be thinking and feeling at the end?

Clear Structures and Signposts. For a spoken argument, you want your organizational structure to be crystal clear. So make sure that you have a sharply delineated beginning, middle, and end and share the structure with listeners. You can do that by remembering to pause between major points of your presentation and to offer signposts marking your movement from one topic to the next. They can be transitions as obvious as next, on the contrary, or finally. Such words act as memory points in your spoken argument and thus should be explicit and concrete: The second crisis point in the breakup of the Soviet Union occurred hard on the heels of the first, rather than just The breakup of the Soviet Union led to another crisis. You can also keep listeners on track by repeating key words and concepts and by using unambiguous topic sentences to introduce each new idea. These transitions can also be highlighted as you come to them on a whiteboard or on presentation slides.

Straightforward Syntax and Concrete Diction. Avoid long, complicated sentences in an oral report and use straightforward syntax (subject-verb-object, for instance, rather than an inversion of that order). Remember, too, that listeners can grasp concrete verbs and nouns more easily than they can mentally process a steady stream of abstractions. When you need to deal with abstract ideas, illustrate them with concrete examples.

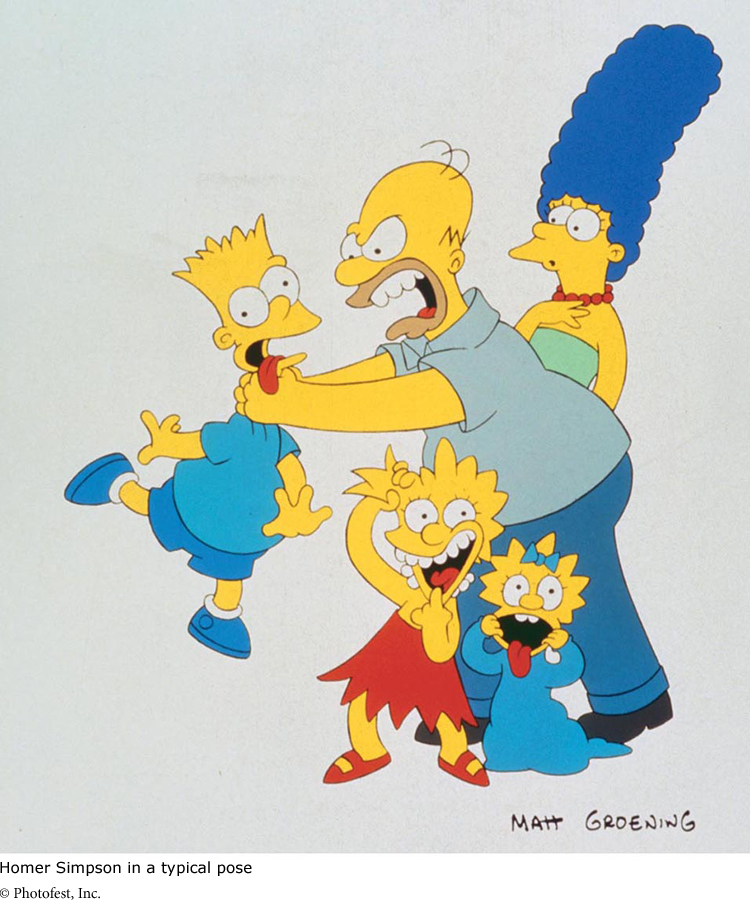

Take a look at the following text that student Ben McCorkle wrote about The Simpsons, first as he prepared it for an essay and then as he adapted it for a live oral and multimedia presentation:

Print Version

The Simpson family has occasionally been described as a nuclear family, which obviously has a double meaning: first, the family consists of two parents and three children, and, second, Homer works at a nuclear power plant with very relaxed safety codes. The overused label “dysfunctional,” when applied to the Simpsons, suddenly takes on new meaning. Every episode seems to include a scene in which son Bart is being choked by his father, the baby is being neglected, or Homer is sitting in a drunken stupor transfixed by the television screen. The comedy in these scenes comes from the exaggeration of commonplace household events (although some talk shows and news programs would have us believe that these exaggerations are not confined to the madcap world of cartoons).

— Ben McCorkle, “The Simpsons: A Mirror of Society”

Oral Version (with a visual illustration)

What does it mean to describe the Simpsons as a nuclear family? Clearly, a double meaning is at work. First, the Simpsons fit the dictionary meaning — a family unit consisting of two parents and some children. The second meaning, however, packs more of a punch. You see, Homer works at a nuclear power plant [pause here] with very relaxed safety codes!

Still another overused family label describes the Simpsons. Did everyone guess I was going to say dysfunctional? And like nuclear, when it comes to the Simpsons, dysfunctional takes on a whole new meaning.

Remember the scene when Bart is being choked by his father?

How about the many times the baby is being neglected?

Or the classic view — Homer sitting in a stupor transfixed by the TV screen!

My point here is that the comedy in these scenes often comes from double meanings — and from a lot of exaggeration of everyday household events.

Note that the second version presents the same information as the first, but this time it’s written to be heard. The revision uses simpler syntax, so the argument is easy to listen to, and employs signposts, repetition, a list, and italicized words to prompt the speaker to give special emphasis where needed.

RESPOND •

Take three or four paragraphs from an essay that you’ve recently written. Then, following the guidelines in this chapter, rewrite the passage to be heard by a live audience. Finally, make a list of every change that you made.

Repetition, Parallelism, and Climactic Order. Whether they’re used alone or in combination, repetition, parallelism, and climactic order are especially appropriate for spoken arguments that sound a call to arms or that seek to rouse the emotions of an audience. Perhaps no person in the twentieth century used them more effectively than Martin Luther King Jr., whose sermons and speeches helped to spearhead the civil rights movement. Standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., on August 23, 1963, with hundreds of thousands of marchers before him, King called on the nation to make good on the “promissory note” represented by the Emancipation Proclamation.

Look at the way that King uses repetition, parallelism, and climactic order in the following paragraph to invoke a nation to action:

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check — a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. There is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquillizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God’s children. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

— Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream” (emphasis added)

The italicized words highlight the way that King uses repetition to drum home his theme and a series of powerful verb phrases (to rise, to open, to lift) to build to a strong climax. These stylistic choices, together with the vivid image of the “bad check,” help to make King’s speech powerful, persuasive — and memorable.

You don’t have to be as highly skilled as King to take advantage of the power of repetition and parallelism. Simply repeating a key word in your argument can impress it on your audience, as can arranging parts of sentences or items in a list in parallel order.

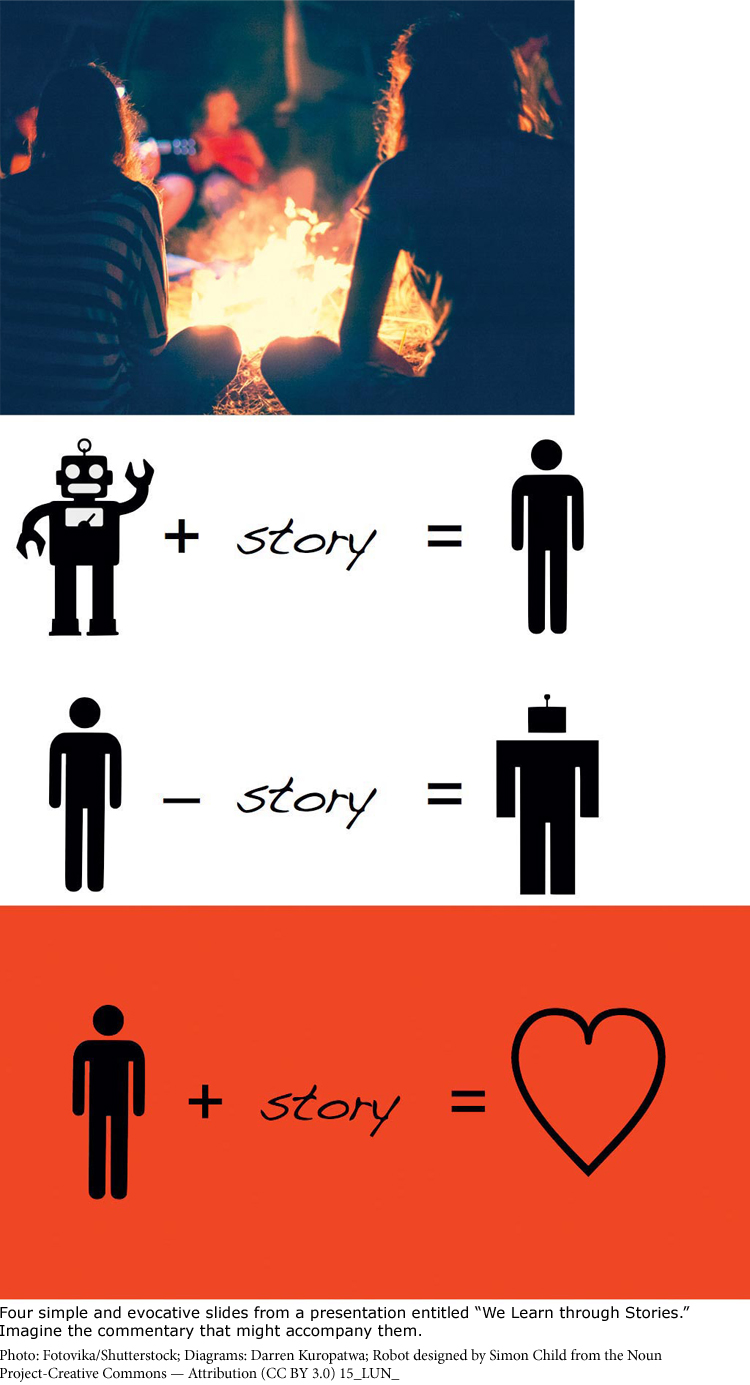

Choose Media to Fit Your Subject

Visual materials — charts, graphs, posters, and presentation slides — are major tools for conveying your message and supporting your claims. People are so accustomed to visual (and aural) texts that they genuinely expect to see them in most oral reports. And, in many cases, a picture, video, or graph can truly be worth a thousand words. (For more about visual argument, see Chapter 14.)

Successful Use of Visuals. Be certain that any visuals that you use are large enough to be seen by all members of your audience. If you use slides or overhead projections, the information on each frame should be simple, clear, and easy to process. For slides, use 24-point type for major headings, 18 point for subheadings, and at least 14 point for other text. Remember, too, to limit the number of words per slide. The same rules of clarity and simplicity hold true for posters, flip charts, and whiteboards. (Note that if your presentation is based on source materials — either text or images — remember to include a slide that lists all those sources at the end of the presentation.)

Use presentation software to furnish an overview for a report or lecture and to give visual information and signposts to listeners. Audiences will be grateful to see the people you are discussing, the key data points you are addressing, the movement of your argument as it develops. But if you’ve watched many oral presentations, you’re sure to have seen some bad ones. Perhaps nothing is deadlier than a speaker who stands up and just reads from each screen. Do this and you’ll just put people to sleep. Also remember not to turn your back on your audience when you refer to these visuals. And if you prepare supplementary materials (such as bibliographies or other handouts), don’t distribute them until the audience actually needs them, or wait until the end of the presentation so that they don’t distract listeners from your spoken arguments. (For advice on creating multimedia arguments, see Chapter 16.)

The best way to test the effectiveness of any images, slides, or other visuals is to try them out on friends, family members, classmates, or roommates. If they don’t get the meaning of the visuals right away, revise and try again.

Accommodations for Everyone. Remember that visuals and accompanying media tools can help make your presentation accessible but that some members of your audience may not be able to see your presentation or may have trouble seeing or hearing them. Here are a few key rules to remember:

Use words to describe projected images. Something as simple as “That’s Eleanor Roosevelt in 1944” can help even sight-impaired audience members appreciate what’s on a screen.

If you use video, take the time to label sounds that might not be audible to audience members who are hearing impaired. (Be sure your equipment is caption capable and use the captions; they can be helpful to everyone when audio quality is poor.)

For a lecture, consider providing a written handout that summarizes your argument or putting the text on an overhead projector — for those who learn better by reading and listening.

Deliver a Good Show

In spite of your best preparation, you may feel some anxiety before a live presentation. This is natural. (According to one Gallup poll, Americans often identify public speaking as a major fear — scarier than possible attacks from outer space.) Experienced speakers say that they have strategies for dealing with anxiety, and even suggest that a little nervousness — and its accompanying adrenaline — can work to a speaker’s advantage.

The most effective strategy seems to be simply knowing your topic and material thoroughly. Confidence in your own knowledge goes a long way toward making you an eloquent speaker. In addition to being well prepared, you may want to try some of the following strategies:

Practice a number of times, running through every part of the presentation. Leave nothing out, even audio or video clips. Work with the equipment you intend to use so that you are familiar with it. It also may help to visualize your presentation, imagining the scene in your mind as you run through your materials.

Time your presentation to make sure you stay within your allotted slot.

Tape yourself (video, if possible) at least once so that you can listen to your voice. Tone of voice and body language can dispose audiences for — or against — speakers. For most oral arguments, you want to develop a tone that conveys commitment to your position as well as respect for your audience.

Think about how you’ll dress for your presentation, remembering that audience members notice how a speaker looks. Dressing for a presentation depends on what’s appropriate for your topic, audience, and setting, but experienced speakers choose clothes that are comfortable, allow easy movement, and aren’t overly casual. Dressing up indicates that you take pride in your appearance, have confidence in your argument, and respect your audience. (Notice George Chidiac’s bow tie in the opening photo in Chapter 15, “Presenting Arguments”.)

Get some rest before the presentation, and avoid consuming too much caffeine.

Relax! Consider doing some deep-breathing exercises. Then pause just before you begin, concentrating on your opening lines.

Maintain eye contact with members of your audience. Speak to them, not to your text or to the floor.

Interact with the audience whenever possible; doing so will often help you relax and even have some fun.

Most speakers make a stronger impression standing than sitting, so stand if you have that option. Moving around a bit may help you maintain good eye contact.

Remember to allow time for audience responses and questions. Keep your answers brief so that others may join the conversation.

Finally, at the very end of your presentation, thank the audience for its attention to your arguments.

A Note about Webcasts: Live Presentations over the Web

This discussion of live oral presentations has assumed that you’ll be speaking before an audience in the same room with you. Increasingly, though — especially in business, industry, and science — the presentations you make will be live, but you won’t occupy the same physical space as the audience. Instead, you might be in front of a camera that will capture your voice and image and relay them via the Web to attendees who might be anywhere in the world. In another type of Webcast, participants can see only your slides or the software that you’re demonstrating, using a screen-capture relay without cameras: you’re not visible but still speaking live.

In either case, most of the strategies that work well for oral presentations with an in-house audience will continue to serve in Webcast environments. But there are some significant differences:

Practice is even more important in Webcasts, since you need to be able to access online any slides, documents, video clips, names, dates, and sources that you provide during the Webcast.

Because you can’t make eye contact with audience members, it’s important to remember to look into the camera (if you are using one), at least from time to time. If you’re using a stationary Webcam, perhaps one mounted on your computer, practice standing or sitting without moving out of the frame and yet without looking stiff.

Even though your audience may not be visible to you, assume that if you’re on camera, the Web-based audience can see you. If you slouch, they’ll notice. Assume too that your microphone is always live. Don’t mutter under your breath, for example, when someone else is speaking or asking a question.

RESPOND •

Attend a presentation on your campus, and observe the speaker’s delivery. Note the strategies that the speaker uses to capture and hold your attention (or not). What signpost language and other guides to listening can you detect? How well are visuals integrated into the presentation? What aspects of the speaker’s tone, dress, eye contact, and movement affect your understanding and your appreciation (or lack of it)? What’s most memorable about the presentation, and why? Finally, write up an analysis of this presentation’s effectiveness.