Synthesizing Information

Synthesizing Information

As you gather information, you must find a way to make all the facts, ideas, points of view, and quotations you have encountered work with and for you. The process involves not only reading information and recording data carefully (paying “infotention”), but also pondering and synthesizing it — that is, figuring out how the sources you’ve examined come together to support your specific claims. Synthesis, a form of critical thinking highly valued by business, industry, and other institutions — especially those that reward innovation and creative thinking — is hard work. It almost always involves immersing yourself in your information or data until it feels familiar and natural to you.

At that point, you can begin to look for patterns, themes, and commonalities or striking differences among your sources. Many students use highlighters to help with this process: mark in blue all the parts of sources that mention point A; mark in green those that have to do with issue B; and so on. You are looking for connections among your sources, bringing together what they have to say about your topic in ways you can organize to help support the claim you are making.

You typically begin this process by paraphrasing or summarizing sources so that you understand exactly what they offer and which ideas are essential to your project. You also decide which, if any, sources offer materials you want to quote directly or reproduce (such as an important graph or table). Then you work to introduce such borrowed materials so that readers grasp their significance, and organize them to highlight important relationships. Throughout this review process, use “infotention” strategies by asking questions such as the following:

Which sources help to set the context for your argument? In particular, which items present new information or give audiences an incentive for reading your work?

Which items provide background information that is essential for anyone trying to understand your argument?

Which items help to define, clarify, or explain key concepts of your case? How can these sources be presented or sequenced so that readers appreciate your claims as valid or, at a minimum, reasonable?

Which of your sources might be used to illustrate technical or difficult aspects of your subject? Would it be best to summarize such technical information to make it more accessible, or would direct quotations be more authoritative and convincing?

Which sources (or passages within sources) furnish the best support or evidence for each claim or sub-claim within your argument? Now is the time to group these together so you can decide how to arrange them most effectively.

Which materials do the best job outlining conflicts or offering counterarguments to claims within a project? Which sources might help you address any important objections or rebuttals?

Remember that yours should be the dominant and controlling voice in an argument. You are like the conductor of an orchestra, calling upon separate instruments to work together to create a rich and coherent sound. The least effective academic papers are those that mechanically walk through a string of sources — often just one item per paragraph — without ever getting all these authorities to talk to each other or with the author. Such papers go through the motions but don’t get anywhere. You can do better.

Paraphrasing Sources You Will Use Extensively

In a paraphrase, you put an author’s ideas — including major and minor points — into your own words and sentence structures, following the order the author has given them in the original piece. You usually paraphrase sources that you expect to use heavily in a project. But if you compose your notes well, you may be able to use much of the paraphrased material directly in your paper (with proper citation) because all of the language is your own. A competent paraphrase proves you have read material or data carefully: you demonstrate not only that you know what a source contains but also that you appreciate what it means. There’s an important difference.

Here are guidelines to help you paraphrase accurately and effectively in an academic argument:

Identify the source of the paraphrase, and comment on its significance or the authority of its author.

Respect your sources. When paraphrasing an entire work or any lengthy section of it, cover all its main points and any essential details, following the same order the author uses. If you distort the shape of the material, your notes will be less valuable, especially if you return to them later.

If you’re paraphrasing material that extends over more than one page in the original source, note the placement of page breaks since it is highly likely that you will use only part of the paraphrase in your argument. You will need the page number to cite the specific page of material you want to cite.

Make sure that the paraphrase is in your own words and sentence structures. If you want to include especially memorable or powerful language from the original source, enclose it in quotation marks. (See “Using Quotations Selectively and Strategically” later in this chapter.)

Keep your own comments, elaborations, or reactions separate from the paraphrase itself. Your report on the source should be clear, objective, and free of connotative language.

Collect all the information necessary to create an in-text citation as well as an item in your works cited list or references list. For online materials, be sure you know how to recover the source later.

Label the paraphrase with a note suggesting where and how you intend to use it in your argument.

Recheck to make sure that the words and sentence structures are your own and that they express the author’s meaning accurately.

Here is a passage from linguist David Crystal’s book Language Play, followed by a student’s paraphrase of the passage.

Language play, the arguments suggest, will help the development of pronunciation ability through its focus on the properties of sounds and sound contrasts, such as rhyming. Playing with word endings and decoding the syntax of riddles will help the acquisition of grammar. Readiness to play with words and names, to exchange puns and to engage in nonsense talk, promotes links with semantic development. The kinds of dialogue interaction illustrated above are likely to have consequences for the development of conversational skills. And language play, by its nature, also contributes greatly to what in recent years has been called metalinguistic awareness, which is turning out to be of critical importance to the development of language skills in general and literacy skills in particular (180).

Paraphrase of the Passage from Crystal’s Book

In Language Play, David Crystal argues that playing with language—creating rhymes, figuring out riddles, making puns, playing with names, using inverted words, and so on—helps children figure out a great deal, from the basics of pronunciation and grammar to how to carry on a conversation. This kind of play allows children to understand the overall concept of how language works, a concept that is key to learning to use—and read—language effectively (180).

Summarizing Sources

Unlike a paraphrase, a summary records just the gist of a source or a key idea — that is, only enough information to identify a point you want to emphasize. Once again, this much-shortened version of a source puts any borrowed ideas into your own words. At the research stage, summaries help you identify key points you want to make and, just as important, provide a record of what you have read. In a project itself, a summary helps readers understand the sources you are using.

In the excerpt from his book Does Science Need a Global Language? English and the Future of Research, Scott L. Montgomery uses a bulleted list to summarize the major conclusions of leading language scholars.

Here are some guidelines to help you prepare accurate and helpful summaries:

Identify the thesis or main point in a source and make it the heart of your summary. In a few detailed phrases or sentences, explain to yourself (and readers) what the source accomplishes.

If your summary includes a comment on the source (as it might in the summaries used for annotated bibliographies), be sure that you won’t later confuse your comments with what the source itself asserts.

When using a summary in an argument, identify the source, state its point, and add your own comments about why the material is significant for the argument that you’re making.

Include just enough information to recount the main points you want to cite. A summary is usually much shorter than the original. When you need more information or specific details, you can return to the source itself or prepare a paraphrase.

Use your own words in a summary and keep the language objective and denotative. If you include any language from the original source, enclose it in quotation marks.

Collect all the information necessary to create an in-text citation as well as an item in your works cited list or references list. For online sources without page numbers, record the paragraph, screen, or section number(s) if available.

Label the summary with a note that suggests where and how you intend to use it in your argument.

Recheck the summary to make sure that you’ve captured the author’s meaning accurately and that the wording is entirely your own.

Following is a summary of the David Crystal passage:

In Language Play, David Crystal argues that playing with language helps children figure out how language works, a concept that is key to learning to use—and read—language effectively (180).

Notice that the summary is shorter than the paraphrase shown above.

Using Quotations Selectively and Strategically

To support your argumentative claims, you’ll want to quote (that is, to reproduce an author’s precise words) in at least three kinds of situations:

when the wording expresses a point so well that you cannot improve it or shorten it without weakening it,

when the author is a respected authority whose opinion supports your own ideas powerfully, and/or

when an author or authority challenges or seriously disagrees with others in the field.

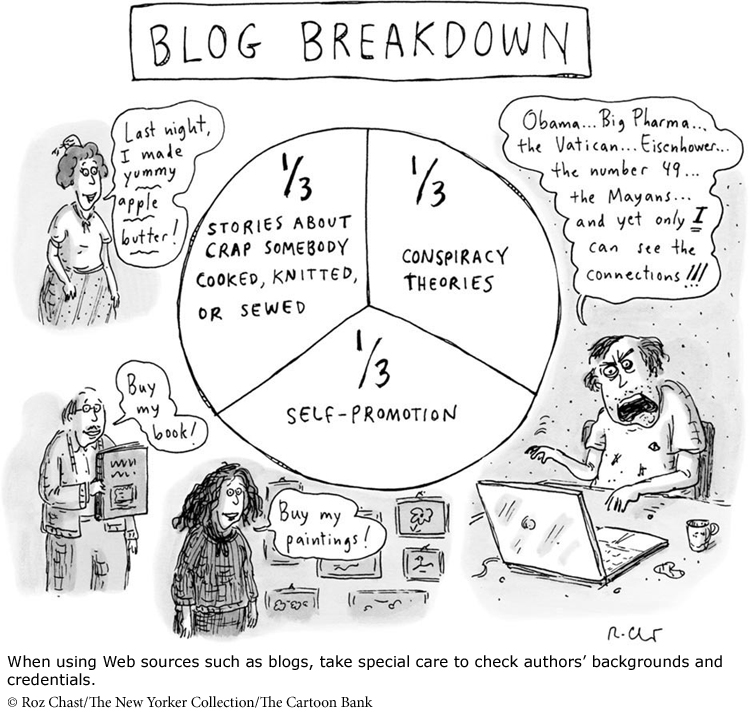

Consider, too, that charts, graphs, and images may also function like direct quotations, providing convincing evidence for your academic argument.

In an argument, quotations from respected authorities will establish your ethos as someone who has sought out experts in the field. Just as important sometimes, direct quotations (such as a memorable phrase in your introduction or a detailed eyewitness account) may capture your readers’ attention. Finally, carefully chosen quotations can broaden the appeal of your argument by drawing on emotion as well as logic, appealing to the reader’s mind and heart. A student who is writing on the ethical issues of bullfighting, for example, might introduce an argument that bullfighting is not a sport by quoting Ernest Hemingway’s comment that “the formal bull-fight is a tragedy, not a sport, and the bull is certain to be killed” and then accompany the quotation with an image such as the one on the next page.

The following guidelines can help you quote sources accurately and effectively:

Quote or reproduce materials that readers will find especially convincing, purposeful, and interesting. You should have a specific reason for every quotation.

Don’t forget the double quotation marks [“ ”] that must surround a direct quotation in American usage. If there’s a quote within a quote, it is surrounded by a pair of single quotation marks [‘ ’]. British usage does just the opposite, and foreign languages often handle direct quotations much differently.

When using a quotation in your argument, introduce its author(s) and follow the quotation with commentary of your own that points out its significance.

Keep quoted material relatively brief. Quote only as much of a passage as is necessary to make your point while still accurately representing what the source actually said.

If the quotation extends over more than one page in the original source, note the placement of page breaks in case you decide to use only part of the quotation in your argument.

In your notes, label a quotation you intend to use with a note that tells you where you think you’ll use it.

Page 445Make sure you have all the information necessary to create an in-text citation as well as an item in your works cited list or references list.

Copy quotations carefully, reproducing the punctuation, capitalization, and spelling exactly as they are in the original. If possible, copy the quotation from a reliable text and paste it directly into your project.

Make sure that quoted phrases, sentences, or passages fit smoothly into your own language. Consider where to begin the quotation to make it work effectively within its surroundings or modify the words you write to work with the quoted material.

Use square brackets if you introduce words of your own into the quotation or make changes to it (“And [more] brain research isn’t going to define further the matter of ‘mind’”).

Use ellipsis marks if you omit material (“And brain research isn’t going to define . . . the matter of ‘mind’ ”).

If you’re quoting a short passage (four lines or less in MLA style; forty words or less in APA style), it should be worked into your text, enclosed by quotation marks. Longer quotations should be set off from the regular text. Begin such a quotation on a new line, indenting every line a half inch or five to seven spaces. Set-off quotations do not need to be enclosed in quotation marks.

Never distort your sources or present them out of context when you quote from them. Misusing sources is a major offense in academic arguments.

Framing Materials You Borrow with Signal Words and Introductions

Because source materials are crucial to the success of arguments, you need to introduce borrowed words and ideas carefully to your readers. Doing so usually calls for using a signal phrase of some kind in the sentence to introduce or frame the source. Often, a signal phrase will precede a quotation. But you need such a marker whenever you introduce borrowed material, as in the following examples:

According to noted primatologist Jane Goodall, the more we learn about the nature of nonhuman animals, the more ethical questions we face about their use in the service of humans.

The more we learn about the nature of nonhuman animals, the more ethical questions we face about their use in the service of humans, according to noted primatologist Jane Goodall.

The more we learn about the nature of nonhuman animals, according to noted primatologist Jane Goodall, the more ethical questions we face about their use in the service of humans.

In each of these sentences, the signal phrase tells readers that you’re drawing on the work of a person named Jane Goodall and that this person is a “noted primatologist.”

Now look at an example that uses a quotation from a source in more than one sentence:

In Job Shift, consultant William Bridges worries about “dejobbing and about what a future shaped by it is going to be like.” Even more worrisome, Bridges argues, is the possibility that “the sense of craft and of professional vocation . . . will break down under the need to earn a fee” (228).

The signal verbs worries and argues add a sense of urgency to the message Bridges offers. They also suggest that the writer either agrees with — or is neutral about — Bridges’s points. Other signal verbs can have a more negative slant, indicating that the point being introduced by the quotation is open to debate and that others (including the writer) might disagree with it. If the writer of the passage above had said, for instance, that Bridges unreasonably contends or that he fantasizes, these signal verbs would carry quite different connotations from those associated with argues.

In some cases, a signal verb may require more complex phrasing to get the writer’s full meaning across:

Bridges recognizes the dangers of changes in work yet refuses to be overcome by them: “The real issue is not how to stop the change but how to provide the necessary knowledge and skills to equip people to operate successfully in this New World” (229).

As these examples illustrate, the signal verb is important because it allows you to characterize the author’s or source’s viewpoint as well as your own — so choose these verbs with care.

David H. Freedman quotes scientists and biology experts in his article “Are Engineered Foods Evil?” Explore how he uses signal verbs. Where might he incorporate more of them?

| Some Frequently Used Signal Verbs | |||

| acknowledges | claims | emphasizes | remarks |

| admits | concludes | expresses | replies |

| advises | concurs | hypothesizes | reports |

| agrees | confirms | interprets | responds |

| allows | criticizes | lists | reveals |

| argues | declares | objects | states |

| asserts | disagrees | observes | suggests |

| believes | discusses | offers | thinks |

| charges | disputes | opposes | writes |

Note that in APA style, these signal verbs should be in a past tense: Blau (1992) claimed; Clark (2001) has concluded.

Using Sources to Clarify and Support Your Own Argument

The best academic arguments often have the flavor of a hearty but focused intellectual conversation. Scholars and scientists create this impression by handling research materials strategically and selectively. Here’s how some college writers use sources to achieve their own specific goals within an academic argument.

Establish context. Taylor Pearson, whose essay “Why You Should Fear Your Toaster More Than Nuclear Power” appears in Chapter 8, sets the context for his argument in the first two sentences, in which he cites a newspaper source (“Japan Nuclear Disaster Tops Scale”) as representative of “headlines everywhere” warning of nuclear crises and the danger of existing nuclear plants. Assuming that these sentences will remind readers of other warnings and hence indicate that this is a highly fraught argument with high emotional stakes, Pearson connects those fears to his own argument by shifting, in the third sentence, into a direct rebuttal of the sources (such fears are “nothing more than media sensationalism”) before stating his thesis: “We need nuclear energy. It’s clean, it’s efficient, it’s economic, and it’s probably the only thing that will enable us to quickly phase out fossil fuels.” It will be up to Pearson in the rest of the essay to explain how, even in a context of public fear, his thesis is defensible:

For the past month or so, headlines everywhere have been warning us of the horrible crises caused by the damaged Japanese nuclear reactors. Titles like “Japan Nuclear Disaster Tops Scale” have fueled a new wave of protests against anything nuclear—namely, the construction of new nuclear plants or even the continued operation of existing plants. However, all this reignited fear of nuclear energy is nothing more than media sensationalism. We need nuclear energy. It’s clean, it’s efficient, it’s economic, and it’s probably the only thing that will enable us to quickly phase out fossil fuels.

Review the literature on a subject. You will often need to tell readers what authorities have already written about your topic, thus connecting them to your own argument. So, in a paper on the effectiveness of peer editing, Susan Wilcox does a very brief “review of the literature” on her subject, pointing to three authorities who support using the method in writing courses. She quotes from the authors and also puts some of their ideas in her own words:

Bostock cites one advantage of peer review as “giving a sense of ownership of the assessment process” (1). Topping expands this view, stating that “peer assessment also involves increased time on task: thinking, comparing, contrasting, and communicating” (254). The extra time spent thinking over the assignment, especially in terms of helping someone else, can draw in the reviewer and lend greater importance to taking the process seriously, especially since the reviewer knows that the classmate is relying on his advice. This also adds an extra layer of accountability for the student; his hard work—or lack thereof—will be seen by peers, not just the instructor. Cassidy notes, “[S]tudents work harder with the knowledge that they will be assessed by their peers” (509): perhaps the knowledge that peer review is coming leads to a better-quality draft to begin with.

The paragraph is straightforward and useful, giving readers an efficient overview of the subject. If they want more information, they can find it by consulting Wilcox’s works cited page.

Introduce a term or define a concept. Quite often in an academic argument, you may need to define a term or explain a concept. Relying on a source may make your job easier and enhance your credibility. That is what Laura Pena achieves in the following paragraph, drawing upon two authorities to explain what teachers mean by a “rubric” when it comes to grading student work:

To understand the controversy surrounding rubrics, it is best to know what a rubric is. According to Heidi Andrade, a professor at SUNY-Albany, a rubric can be defined as “a document that lists criteria and describes varying levels of quality, from excellent to poor, for a specific assignment” (“Self-Assessment” 61). Traditionally, rubrics have been used primarily as grading and evaluation tools (Kohn 12), meaning that a rubric was not used until after students handed their papers in to their teacher. The teacher would then use a rubric to evaluate the students’ papers according to the criteria listed on the rubric.

Note that the first source provides the core definition while information from the second offers a detail important to understanding when and how rubrics are used — a major issue in Pena’s paper. Her selection of sources here serves her thesis while also providing readers with necessary information.

Present technical material. Sources can be especially helpful, too, when material becomes technical or difficult to understand. Writing on your own, you might lack the confidence to handle the complexities of some subjects. While you should challenge yourself to learn a subject well enough to explain it in your own words, there will be times when a quotation from an expert serves both you and your readers. Here is Natalie San Luis dealing with some of the technical differences between mainstream and Black English:

The grammatical rules of mainstream English are more concrete than those of Black English; high school students can’t check out an MLA handbook on Ebonics from their school library. As with all dialects, though, there are certain characteristics of the language that most Black English scholars agree upon.

According to Samy Alim, author of Roc the Mic Right, these characteristics are the “[h]abitual be [which] indicates actions that are continuing or ongoing. . . . Copula absence. . . . Stressed been. . . . Gon [indicating] the future tense. . . . They for possessive. . . . Postvocalic-r. . . . [and] Ank and ang for ‘ink’ and ‘ing’ ” (115). Other scholars have identified “[a]bsence of third-person singular present-tense s. . . . Absence of possessive ’s,” repetition of pronouns, and double negatives (Rickford 111-24).

Note that using ellipses enables San Luis to cover a great deal of ground. Readers not familiar with linguistic terms may have trouble following the quotation, but remember that academic arguments often address audiences comfortable with some degree of complexity.

Develop or support a claim. Even academic audiences expect to be convinced, and one of the most important strategies for a writer is to use sources to amplify or support a claim.

Here is Manasi Deshpande, whose proposal argument appears in Chapter 12, making the following claim: “Although the University has made a concerted and continuing effort to improve access, students and faculty with physical disabilities still suffer from discriminatory hardship, unequal opportunity to succeed, and lack of independence.” See how she weaves sources together in the following paragraph to help support that claim:

The current state of campus accessibility leaves substantial room for improvement. There are approximately 150 academic and administrative buildings on campus (Grant). Eduardo Gardea, intern architect at the Physical Plant, estimates that only about nineteen buildings comply fully with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). According to Penny Seay, PhD, director of the Center for Disability Studies at UT Austin, the ADA in theory “requires every building on campus to be accessible.”

Highlight differences or counterarguments. The sources you encounter in developing a project won’t always agree with each other or you. In academic arguments, you don’t want to hide such differences, but instead point them out honestly and let readers make judgments based upon actual claims. Here is a paragraph in which Laura Pena again presents two views on the use of rubrics as grading tools:

Some naysayers, such as Alfie Kohn, assert that “any form of assessment that encourages students to keep asking, ‘How am I doing?’ is likely to change how they look at themselves and what they’re learning, usually for the worse.” Kohn cites a study that found that students who pay too much attention to the quality of their performance are more likely to chalk up the outcome of an assignment to factors beyond their control, such as innate ability, and are also more likely to give up quickly in the face of a difficult task (14). However, Ross and Rolheiser have found that when students are taught how to properly implement self-assessment tools in the writing process, they are more likely to put more effort and persistence into completing a difficult assignment and may develop higher self-confidence in their writing ability (sec. 2). Building self-confidence in elementary-age writers can be extremely helpful when they tackle more complicated writing endeavors in the future.

In describing Kohn as a “naysayer,” Pena may tip her hand and lose some degree of objectivity. But her thesis has already signaled her support for rubrics as a grading tool, so academic readers will probably not find the connotations of the term inappropriate.

These examples suggest only a few of the ways that sources, either summarized or quoted directly, can be incorporated into an academic argument to support or enhance a writer’s goals. Like these writers, you should think of sources as your copartners in developing and expressing ideas. But you are still in charge.

Avoiding “Patchwriting”

When using sources in an argument, writers — and especially those new to research-based writing — may be tempted to do what Professor Rebecca Moore Howard terms “patchwriting”: stitching together material from Web or other sources without properly paraphrasing or summarizing and with little or no documentation. Here, for example, is a patchwork paragraph about the dangers wind turbines pose to wildlife:

Scientists are discovering that technology with low carbon impact does not mean low environmental or social impacts. That is the case especially with wind turbines, whose long, massive fiberglass blades have been chopping up tens of thousands of birds that fly into them, including golden eagles, red-tailed hawks, burrowing owls, and other raptors in California. Turbines are also killing bats in great numbers. The 420 wind turbines now in use across Pennsylvania killed more than 10,000 bats last year—mostly in the late summer months, according to the State Game Commission. That’s an average of 25 bats per turbine per year, and the Nature Conservancy predicts as many as 2,900 turbines will be set up across the state by 2030. It’s not the spinning blades that kill the bats; instead, their lungs effectively blow up from the rapid pressure drop that occurs as air flows over the turbine blades. But there’s hope we may figure out solutions to these problems because, since we haven’t had too many wind turbines heretofore in the country, we are learning how to manage this new technology as we go.

The paragraph reads well and is full of details. But it would be considered plagiarized (see Chapter 21) because it fails to identify its sources and because most of the material has simply been lifted directly from the Web. How much is actually copied? We’ve highlighted the borrowed material:

Scientists are discovering that technology with low carbon impact does not mean low environmental or social impacts. That is the case especially with wind turbines, whose long, massive fiberglass blades have been chopping up tens of thousands of birds that fly into them, including golden eagles, red-tailed hawks, burrowing owls, and other raptors in California. Turbines are also killing bats in great numbers. The 420 wind turbines now in use across Pennsylvania killed more than 10,000 bats last year—mostly in the late summer months, according to the State Game Commission. That’s an average of 25 bats per turbine per year, and the Nature Conservancy predicts as many as 2,900 turbines will be set up across the state by 2030. It’s not the spinning blades that kill the bats; instead, their lungs effectively blow up from the rapid pressure drop that occurs as air flows over the turbine blades. But there’s hope we may figure out solutions to these problems because, since we haven’t had too many wind turbines heretofore in the country, we are learning how to manage this new technology as we go.

But here’s the point: an academic writer who has gone to the trouble of finding so much information will gain more credit and credibility just by properly identifying, paraphrasing, and quoting the sources used. The resulting paragraph is actually more impressive because it demonstrates how much reading and synthesizing the writer has actually done:

Scientists like George Ledec of the World Bank are discovering that technology with low carbon impact “does not mean low environmental or social impacts” (Tracy). That is the case especially with wind turbines. Their massive blades spinning to create pollution-free electricity are also killing thousands of valuable birds of prey, including eagles, hawks, and owls in California (Rittier). Turbines are also killing bats in great numbers (Thibodeaux). The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reports that 10,000 bats a year are killed by the 420 turbines currently in Pennsylvania. According to the state game commissioner, “That’s an average of 25 bats per turbine per year, and the Nature Conservancy predicts as many as 2,900 turbines will be set up across the state by 2030” (Schwartzel). It’s not the spinning blades that kill the animals; instead, DiscoveryNews explains, “the bats’ lungs effectively blow up from the rapid pressure drop that occurs as air flows over the turbine blades” (Marshall). But there’s hope that scientists can develop turbines less dangerous to animals of all kinds. “We haven’t had too many wind turbines heretofore in the country,” David Cottingham of the Fish and Wildlife Service points out, “so we are learning about it as we go” (Tracy).

Works Cited

Marshall, Jessica. “Wind Turbines Kill Bats without Impact.” Discovery News, 25 Aug. 2008, news.discovery.om/20111112-turbinebats/.

Rittier, John. “Wind Turbines Taking Toll on Birds of Prey.” USA Today, 4 Jan. 2005, usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-01-04-windmills-usat_x.htm.

Schwartzel, Erich. “Pa. Wind Turbines Deadly to Bats, Costly to Farmers.” Post-Gazette.com, 17 July 2011, www.post-gazette.com/business/businessnews/2011/07/17/Pa-wind-turbines-deadly-to-bats-costly-to-farmers/stories/201107170197.

Thibodeaux, Julie. “Bats Getting Caught in Texas Wind Turbines.” PegasusNews.com, 9 Nov. 2011, www.pegasusnews.com/2011/11/09/bats-getting-caught-in-texas-wind-turbines/.

Tracy, Ryan. “Wildlife Slows Wind Power.” The Wall Street Journal, 10 Dec. 2011, www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970203501304577088593307132850.

RESPOND •

Select one of the essays from Chapters 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, or 17. Following the guidelines in this chapter, write a paraphrase of the essay that you might use subsequently in an academic argument. Be careful to describe the essay accurately and to note on what pages specific ideas or claims are located. The language of the paraphrase should be entirely your own — though you may include direct quotations of phrases, sentences, or longer passages you would likely use in a paper. Be sure these quotations are introduced and cited in your paraphrase: Pearson claims that nuclear power is safe, even asserting that “your toaster is far more likely to kill you than any nuclear power plant” (175). When you are done, trade your paraphrase with a partner to get feedback on its clarity and accuracy.

Summarize three readings or fairly lengthy passages from Parts 1–3 of this book, following the guidelines in this chapter. Open the item with a correct MLA or APA citation for the piece (see Chapter 22). Then provide the summary itself. Follow up with a one- or two-sentence evaluation of the work describing its potential value as a source in an academic argument. In effect, you will be preparing three items that might appear in an annotated bibliography. Here’s an example:

Pearson, Taylor. “Why You Should Fear Your Toaster More Than Nuclear Power.” Everything’s an Argument, by Andrea A. Lunsford and John J. Ruszkiewicz, 7th ed., Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016, pp. 174-79. Argues that since the dangers of nuclear power (death, radiation, waste) are actually less than those of energy sources we rely on today, nuclear plants represent the only practical way to generate the power we need and still reduce greenhouse gases. The journalistic piece provides many interesting facts about nuclear energy, but is informally documented and so does not identify its sources in detail or include a bibliography.

Working with a partner, agree upon an essay that you will both read from Chapters 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, or 17, examining it as a potential source for a research argument. As you read it, choose about a half-dozen words, phrases, or short passages that you would likely quote if you used the essay in a paper and attach a frame or signal phrase to each quotation. Then compare the passages you selected to quote with those your partner culled from the same essay. How do your choices of quoted material create an image or ethos for the original author that differs from the one your partner has created? How do the signal phrases shape a reader’s sense of the author’s position? Which set of quotations best represents the author’s argument? Why?

Select one of the essays from Chapters 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, or 17 to examine the different ways an author uses source materials to support claims. Begin by highlighting the signal phrases you find attached to borrowed ideas or direct quotations. How well do they introduce or frame this material? Then categorize the various ways the author actually uses particular sources. For example, look for sources that provide context for the topic, review the scholarly literature, define key concepts or terms, explain technical details, furnish evidence, or lay out contrary opinions. When you are done, write a paragraph assessing the author’s handling of sources in the piece. Are the borrowed materials integrated well with the author’s own thoughts? Do the sources represent an effective synthesis of ideas?