10.1 Basic Motivational Concepts, Affiliation, and Achievement

Motivational Concepts

10-

motivation a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior.

Psychologists define motivation as a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior. Our motivations arise from the interplay between nature (the bodily “push”) and nurture (the “pulls” from our thought processes and culture).

If our motivations get hijacked, our lives go awry. Those with substance use disorder, for example, may find their cravings for an addictive substance override their longings for sustenance, safety, and social support.

In their attempts to understand ordinary motivated behavior, psychologists have viewed it from four perspectives:

Instinct theory (now replaced by the evolutionary perspective) focuses on genetically predisposed behaviors.

Drive-

reduction theory focuses on how we respond to our inner pushes.Arousal theory focuses on finding the right level of stimulation.

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs focuses on the priority of some needs over others.

Instincts and Evolutionary Psychology

instinct a complex behavior that is rigidly patterned throughout a species and is unlearned.

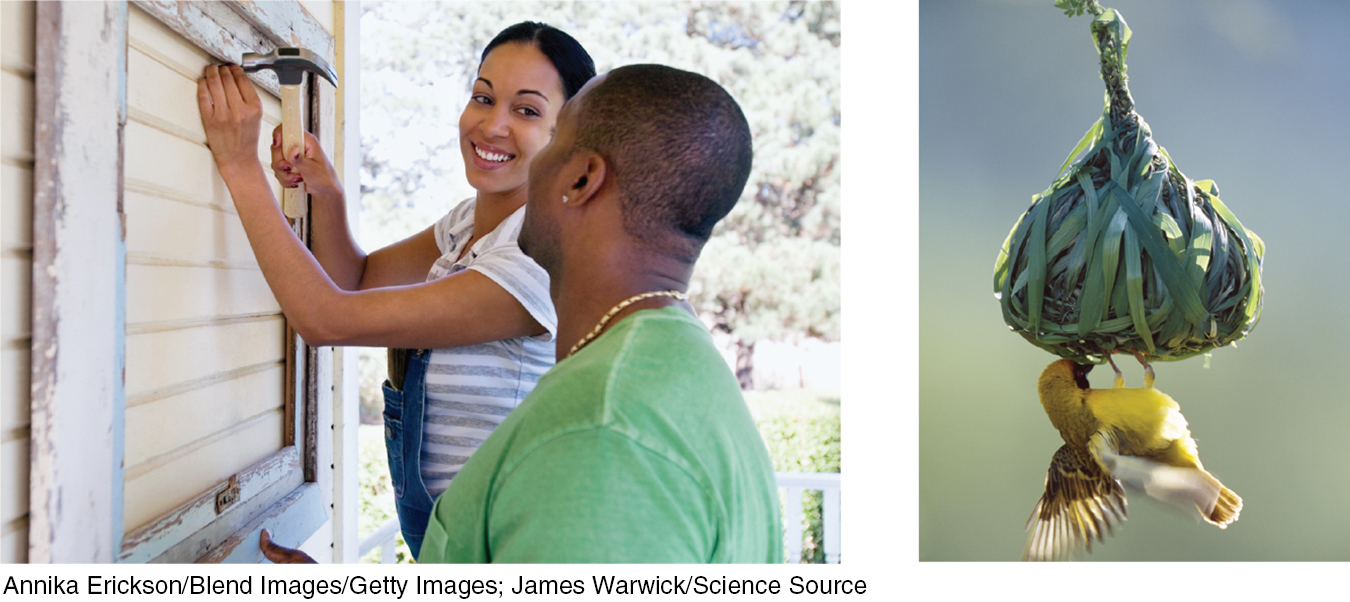

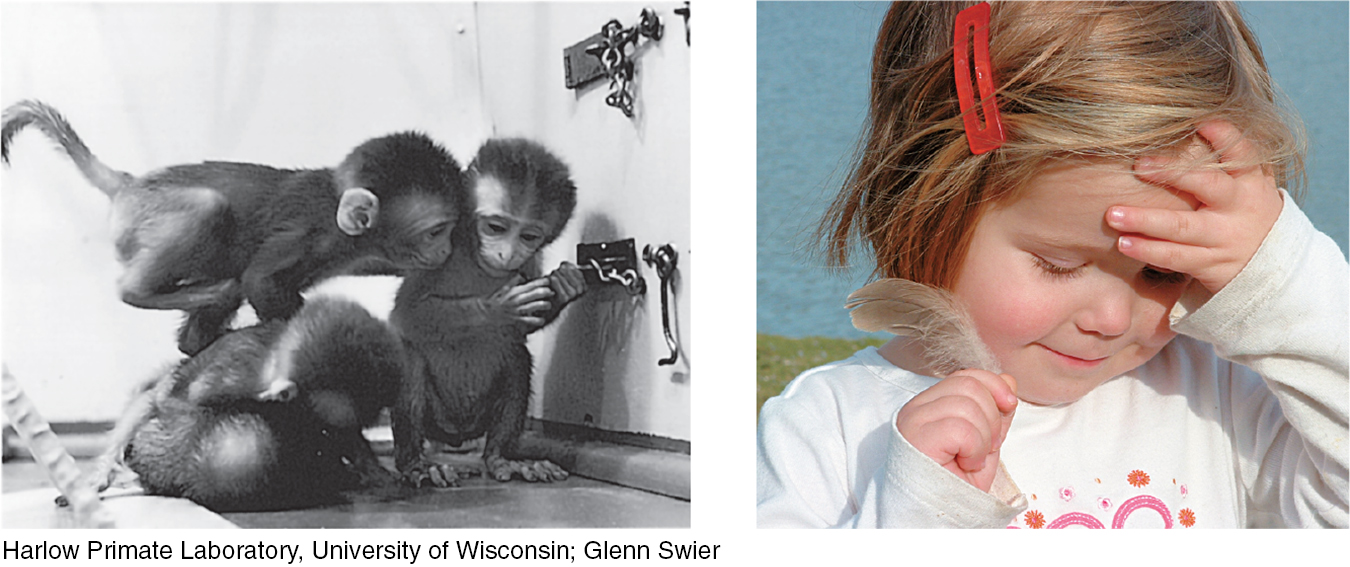

To qualify as an instinct, a complex behavior must have a fixed pattern throughout a species and be unlearned (Tinbergen, 1951). Such behaviors are common in other species and include imprinting in birds and the return of salmon to their birthplace. A few human behaviors, such as infants’ innate reflexes to root for a nipple and suck, exhibit unlearned fixed patterns, but many more are directed by both physiological needs and psychological wants.

Although instincts cannot explain most human motives, the underlying assumption continues in evolutionary psychology: Genes do predispose some species-

Drives and Incentives

drive-reduction theory the idea that a physiological need creates an aroused tension state (a drive) that motivates an organism to satisfy the need.

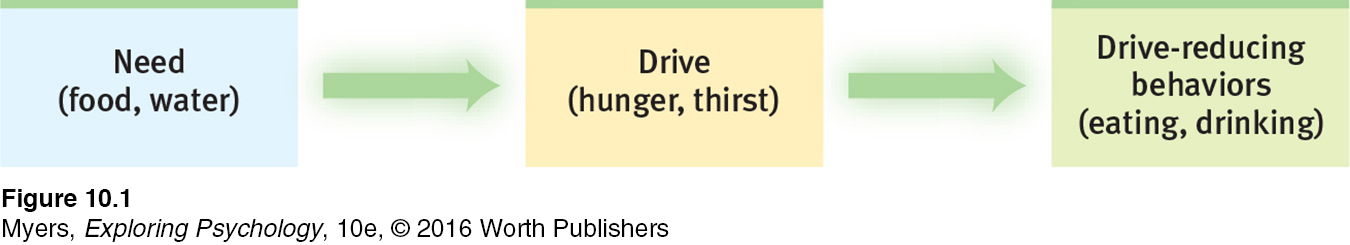

In addition to our predispositions, we have drives. Physiological needs (such as for food or water) create an aroused, motivated state—

homeostasis a tendency to maintain a balanced or constant internal state; the regulation of any aspect of body chemistry, such as blood glucose, around a particular level.

Drive reduction is one way our bodies strive for homeostasis (literally “staying the same”)—the maintenance of a steady internal state. For example, our body regulates its temperature in a way similar to a room’s thermostat. Both systems operate through feedback loops: Sensors feed room temperature to a control device. If the room’s temperature cools, the control device switches on the furnace. Likewise, if our body’s temperature cools, our blood vessels constrict (to conserve warmth) and we feel driven to put on more clothes or seek a warmer environment (FIGURE 10.1).

incentive a positive or negative environmental stimulus that motivates behavior.

Not only are we pushed by our need to reduce drives, we also are pulled by incentives—positive or negative environmental stimuli that lure or repel us. This is one way our individual learning histories influence our motives. Depending on our learning, the aroma of good food, whether fresh roasted peanuts or toasted ants, can motivate our behavior. So can the sight of those we find attractive or threatening.

When there is both a need and an incentive, we feel strongly driven. The food-

Optimum Arousal

We are much more than homeostatic systems, however. Some motivated behaviors actually increase rather than decrease arousal. Well-

So, human motivation aims not to eliminate arousal but to seek optimum levels of arousal. Having all our biological needs satisfied, we feel driven to experience stimulation and we hunger for information. Lacking stimulation, we feel bored and look for a way to increase arousal to some optimum level. If left alone by themselves, most people prefer to do something—

Yerkes-Dodson law the principle that performance increases with arousal only up to a point, beyond which performance decreases.

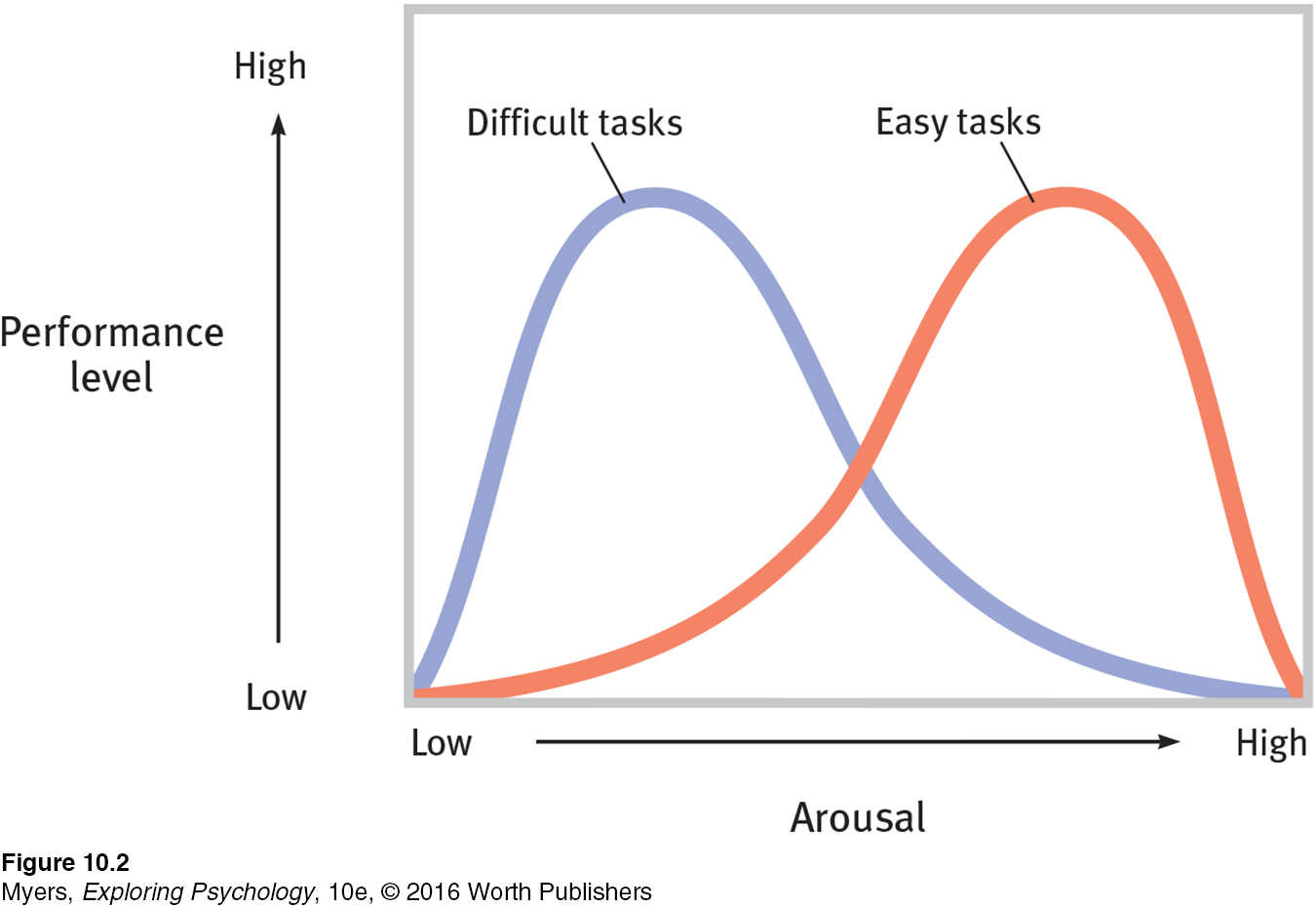

Two early twentieth-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Performance peaks at lower levels of arousal for difficult tasks, and at higher levels for easy or well-

learned tasks. (1) How might this phenomenon affect runners? (2) How might this phenomenon affect anxious test- takers facing a difficult exam? (3) How might the performance of anxious students be affected by relaxation training? ANSWER: (1) Runners, who are executing a well-learned task, tend to excel when aroused by competition. (2) High anxiety in test- takers, who are completing a difficult task, may disrupt their performance. (3) Teaching anxious students how to relax before an exam can enable them to perform better (Hembree, 1988).

A Hierarchy of Motives

“Hunger is the most urgent form of poverty.”

Alliance to End Hunger, 2002

Some needs take priority over others. At this moment, with your needs for air and water hopefully satisfied, other motives—

To test your understanding of the hierarchy of needs, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Building Maslow’s Hierarchy.

To test your understanding of the hierarchy of needs, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Building Maslow’s Hierarchy.

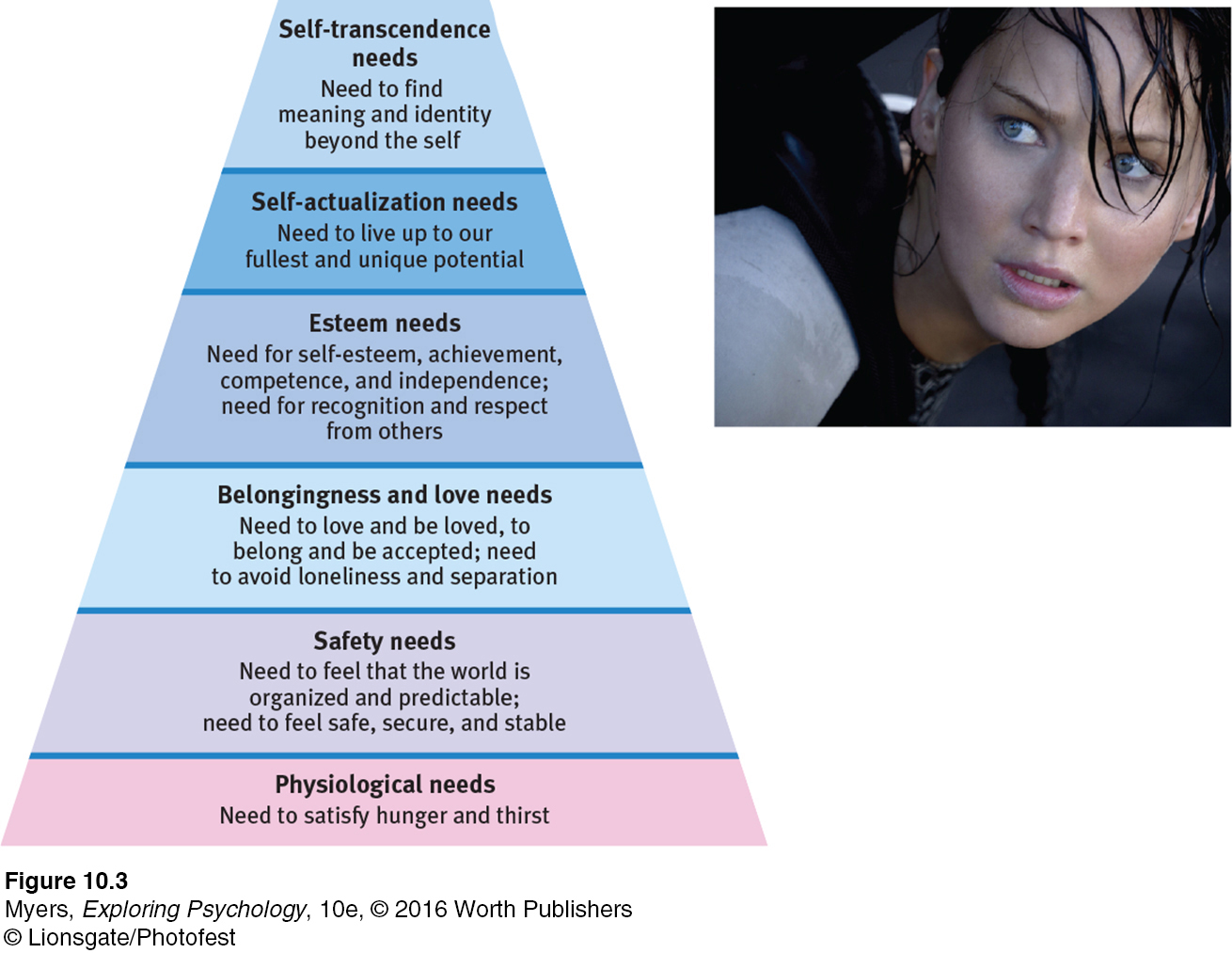

hierarchy of needs Maslow’s pyramid of human needs, beginning at the base with physiological needs that must first be satisfied before higher-

Abraham Maslow (1970) described these priorities as a hierarchy of needs (FIGURE 10.3). At the base of this pyramid are our physiological needs, such as those for food and water. Only if these needs are met are we prompted to meet our need for safety, and then to satisfy our human needs to give and receive love and to enjoy self-

Near the end of his life, Maslow proposed that some of us also reach a level of self-

The order of Maslow’s hierarchy is not universally fixed: People have starved themselves to make a political statement. Culture also influences our priorities: Self-

Nevertheless, the simple idea that some motives are more compelling than others provides a framework for thinking about motivation. Worldwide life-

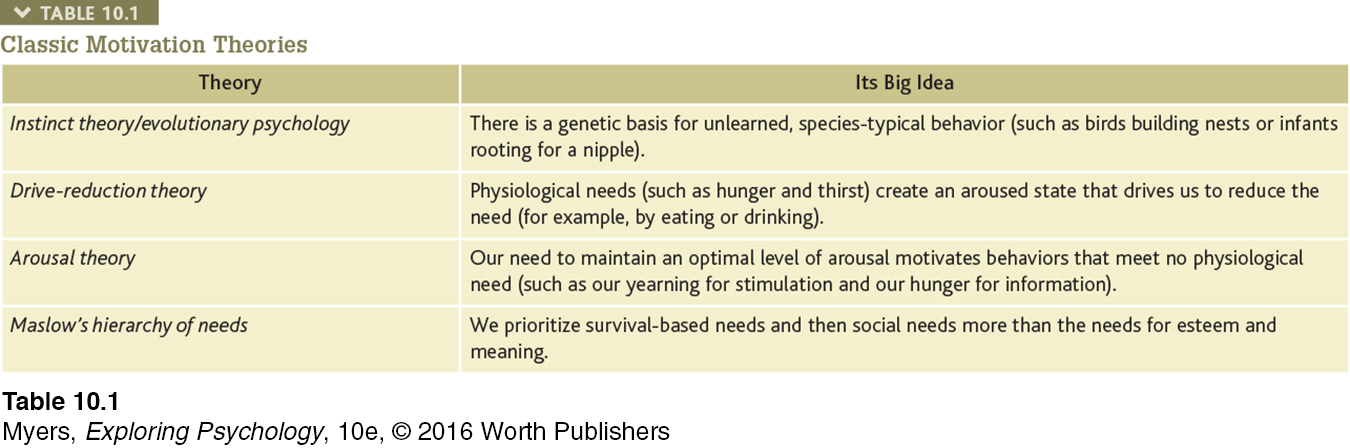

With these classic motivation theories in mind (see TABLE 10.1), let’s now take a closer look at two specific, higher-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

After hours of driving alone in an unfamiliar city, you finally see a diner. Although it looks deserted and a little creepy, you stop because you are really hungry and thirsty. How would Maslow's hierarchy of needs explain your behavior?

The Need to Belong

10-

affiliation need the need to build relationships and to feel part of a group.

We are what Greek philosopher Aristotle called the social animal. Cut off from friends or family—

The Benefits of Belonging

Social bonds boosted our early ancestors’ chances of survival. Adults who formed attachments were more likely to reproduce and to co-

Cooperation also enhanced survival. In solo combat, our ancestors were not the toughest predators. But as hunters, they learned that six hands were better than two. As food gatherers, they gained protection from two-

Do you have close friends—

“We must love one another or die.”

W. H. Auden, “September 1, 1939”

The need to belong colors our thoughts and emotions. We spend a great deal of time thinking about actual and hoped-

Consider: What was your most satisfying moment in the past week? Researchers asked that question of American and South Korean collegians, then asked them to rate how much that moment had satisfied various needs (Sheldon et al., 2001). In both countries, the peak moment had contributed most to satisfaction of self-

Is it surprising, then, that so much of our social behavior aims to increase our feelings of belonging? To gain acceptance, we generally conform to group standards. We monitor our behavior, hoping to make a good impression. We spend billions on clothes, cosmetics, and diet and fitness aids—

Thrown together in groups at school, at work, on a hiking trip, we behave like magnets, moving closer, forming bonds. Parting, we feel distress. We promise to call, to write, to return for reunions. By drawing a sharp circle around “us,” the need to belong feeds both deep attachments and menacing threats. Out of our need to define a “we” come loving families, faithful friendships, and team spirit, but also teen gangs, ethnic rivalries, and fanatic nationalism.

Feelings of love activate brain reward and safety systems. In one experiment involving exposure to heat, deeply-

Even when bad relationships break, people suffer. In one 16-

Children who move through a series of foster homes or through repeated family relocations know the fear of being alone. After repeated disruption of budding attachments, they may have difficulty forming deep attachments (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). The evidence is clearest at the extremes: Children who grow up in institutions without a sense of belonging to anyone, or who are locked away at home and severely neglected often become withdrawn, frightened, speechless.

No matter how secure our early years were, we all experience anxiety, loneliness, jealousy, or guilt when something threatens or dissolves our social ties. Much as life’s best moments occur when close relationships begin—

For immigrants and refugees moving alone to new places, the stress and loneliness can be depressing. After years of placing individual families in isolated communities, U.S. immigration policies began to encourage chain migration (Pipher, 2002). The second refugee Sudanese family settling in a town generally has an easier adjustment than the first.

Social isolation can put us at risk for mental decline and ill health (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Lonely older adults make more doctor visits (Gerst-

The Pain of Being Shut Out

Can you recall feeling excluded or ignored or shunned? Perhaps you received the silent treatment. Perhaps people avoided you or averted their eyes in your presence or even mocked you behind your back. If you are like others, even being in a group speaking a different language may have left you feeling excluded, a linguistic outsider (Dotan-

ostracism deliberate social exclusion of individuals or groups.

All these experiences are instances of ostracism—of social exclusion (Williams et al., 2007, 2009). Worldwide, humans use many forms of ostracism—

Being shunned—

To experience ostracism is to experience real pain, as social psychologists Kipling Williams and his colleagues were surprised to discover in their studies of exclusion on social media (Gonsalkorale & Williams, 2006). (Perhaps you can recall the feeling of being unfriended, ignored, or having few followers on a social networking site, or of having a text message or e-

“Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for 23 hours a day, sometimes for months or even years at a time? … And if those individuals are ultimately released, how are they ever going to adapt?”

U.S. President Barack Obama, July 14, 2015, expressing bipartisan concerns about the solitary confinement of some 75,000 American prisoners

Pain, whatever its source, focuses our attention and motivates corrective action. Rejected and unable to remedy the situation, people may relieve stress by seeking new friends, eating calorie-

“If no one turned around when we entered, answered when we spoke, or minded that we did, but if every person we met ‘cut us dead,’ and acted as if we were non-

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How have students reacted in studies where they were made to feel rejected and unwanted? What helps explain these results?

Connecting and Social Networking

10-

As social creatures, we live for connection. Researcher George Vaillant (2013) was asked what he had learned from studying 238 Harvard University men from the 1930s to the end of their lives. He replied, “Happiness is love.” South Africans have a word for the human bonds that define us all: Ubuntu [oo-

“Facebook … was built to accomplish a social mission—

Facebook CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, 2012

MOBILE NETWORKS AND SOCIAL MEDIA Look around and see humans connecting: talking, tweeting, texting, posting, chatting, social gaming, e-

At the end of 2014, the world had 7.3 billion people and 6.9 billion mobile cell-

phone subscriptions (ITU, 2015). But phone talking accounts for less than half of U.S. mobile network traffic (Wortham, 2010). In Canada and elsewhere, e- mailing is being displaced by texting, social media sites, and other messaging technology (IPSOS, 2010a). Speedy texting is not really writing, said one observer (McWhorter, 2012), but rather a new form of conversation— “fingered speech.” Three in four U.S. teens text. Half (mostly females) send 60 or more texts daily (Lenhart, 2012). For many, it’s as though friends, for better and worse, are always present.

How many of us are using social networking sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, or Snapchat? Among 2014’s entering American college students, 94 percent were (Eagan et al., 2014). With so many of your friends on a social network, its lure becomes hard to resist. Such is our need to belong. Check in or miss out.

THE NET RESULT: SOCIAL EFFECTS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING By connecting like-

HAVE SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES MADE US MORE, OR LESS, SOCIALLY ISOLATED? Lonely people tend to spend greater-

DOES ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATION STIMULATE HEALTHY SELF-

DO SOCIAL NETWORKS REFLECT PEOPLE’S ACTUAL PERSONALITIES? We’ve all heard stories of online predators hiding behind false personalities, values, and motives. Generally, however, social network profiles and posts reveal a person’s real personality. In one study, participants completed a personality test twice. In one test, they described their “actual personality”; in the other, they described their “ideal self.” Other volunteers then used the participants’ Facebook profiles to create an independent set of personality ratings. The Facebook profile ratings were much closer to the participants’ actual personalities than to their ideal personalities (Back et al., 2010). In another study, people who seemed most likable on their Facebook page also seemed most likable in face-

narcissism excessive self-

DOES SOCIAL NETWORKING PROMOTE NARCISSISM? Narcissistic people are self-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Random Assignment for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Random Assignment for a helpful tutorial animation.

For narcissists, social networking sites are more than a gathering place; they are a feeding trough. In one study, college students were randomly assigned either to edit and explain their online profiles for 15 minutes, or to use that time to study and explain a Google Maps routing (Freeman & Twenge, 2010). After completing their tasks, all were tested. Who then scored higher on a narcissism measure? Those who had spent the time focused on themselves.

MAINTAINING BALANCE AND FOCUS It will come as no surprise that excessive online socializing and gaming have been associated with lower grades (Chen & Fu, 2008; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010; Walsh et al., 2013). In one U.S. survey, 47 percent of the heaviest users of the Internet and other media were receiving mostly C grades or lower, as were just 23 percent of the lightest users (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010).

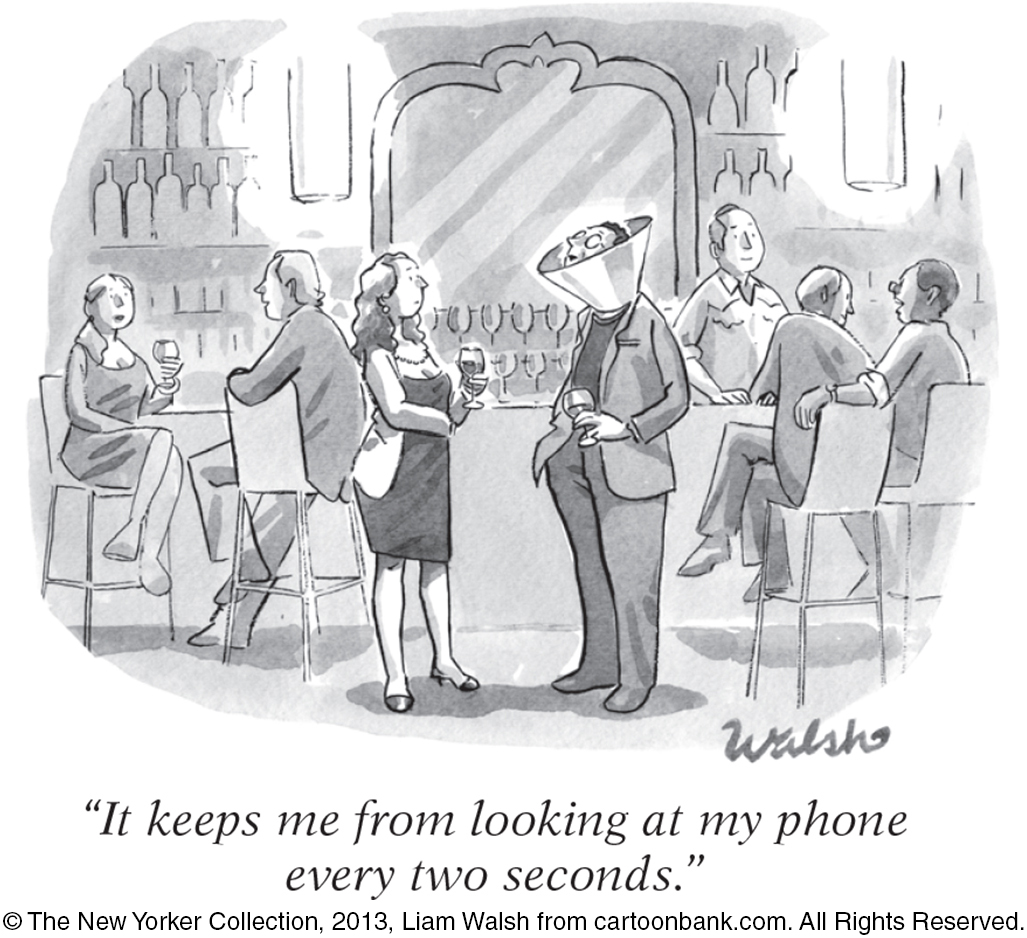

In today’s world, each of us is challenged to maintain a healthy balance between our real-

Monitor your time. Keep a log of how you use your time. Then ask yourself, “Does my time use reflect my priorities? Am I spending more or less time online than I intended? Is my time online interfering with school or work performance?”

Monitor your feelings. Ask yourself, “Am I emotionally distracted by my online interests? When I disconnect and move to another activity, how do I feel? Have family or friends commented on this?”

Hide from your more distracting online friends when necessary. And in your own postings, practice the golden rule. Ask yourself, “Is this something I’d care about if someone else posted it?”

Page 375When studying, get in the practice of checking your phone only once per hour. Selective attention—

the flashlight of your mind— can be in only one place at a time. When we try to do two things at once, we don’t do either one of them very well (Willingham, 2010). If you want to study or work productively, resist the temptation to be always available. Turn your phone face down and turn off all sound and vibration so that you choose when to attend to it. On your laptop, disable sound alerts and pop- ups. (To avoid distraction, I [DM] am proofing and editing this chapter in a coffee shop without Wi- Fi.) Try a social networking fast (give it up for an hour, a day, or a week) or a time-

controlled social media diet (check in only after homework is done, or only during a lunch break). Take notes on what you’re losing and gaining on your new “diet.”Refocus by taking a nature walk. People learn better after a peaceful walk in the woods or a park, which—

unlike a walk on a busy street— refreshes our capacity for focused attention (Berman et al., 2008). Connecting with nature boosts our spirits and sharpens our minds (Zelenski & Nisbet, 2014).

As psychologist Steven Pinker (2010) said, “The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Social networking tends to (strengthen/weaken) your relationships with people you already know, (increase/decrease) your self-disclosure, and (reveal/hide) your true personality.

Achievement Motivation

10-

achievement motivation a desire for significant accomplishment; for mastery of skills or ideas; for control; and for attaining a high standard.

Some motives seem to have little obvious survival value. Billionaires may be motivated to make ever more money, reality TV stars to attract ever more social media followers, politicians to achieve ever more power, daredevils to seek ever greater thrills. Such motives seem not to diminish when they are fed. The more we achieve, the more we may need to achieve. Psychologist Henry Murray (1938) defined achievement motivation as a desire for significant accomplishment, for mastering skills or ideas, for control, and for attaining a high standard.

Thanks to their persistence and eagerness for challenge, people with high achievement motivation do achieve more. One study followed the lives of 1528 California children whose intelligence test scores were in the top 1 percent. Forty years later, when researchers compared those who were most and least successful professionally, they found a motivational difference. Those most successful were more ambitious, energetic, and persistent. As children, they had more active hobbies. As adults, they participated in more groups and sports (Goleman, 1980). Gifted children are able learners. Accomplished adults are tenacious doers. Most of us are energetic doers when starting and when finishing a project. It’s easiest—

“Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Thomas Edison (1847–

In other studies of both secondary school and university students, self-

Discipline also refines talent. By their early twenties, top violinists have accumulated thousands of lifetime practice hours—

grit in psychology, passion and perseverance in the pursuit of long-

Duckworth and Seligman have a name for this passionate dedication to an ambitious, long-

Although intelligence is distributed like a bell curve, achievements are not. That tells us that achievement involves much more than raw ability. That is why organizational psychologists seek ways to engage and motivate ordinary people doing ordinary jobs (see Appendix B: Psychology at Work). And that is why training students in hardiness—resilience under stress—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What have researchers found to be an even better predictor of school performance than intelligence test scores?

REVIEW Basic Motivational Concepts, Affiliation, and Achievement

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

10-

Question

10-

Question

10-

Question

10-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

motivation (p. 366) instinct (p. 366) drive- homeostasis (p. 367) incentive (p. 367) Yerkes- hierarchy of needs (p. 368) affiliation need (p. 369) ostracism (p. 371) narcissism (p. 374) achievement motivation (p. 375) grit (p. 376) | excessive self- a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior. a positive or negative environmental stimulus that motivates behavior. a desire for significant accomplishment; for mastery of skills or ideas; for control; and for attaining a high standard. the idea that a physiological need creates an aroused tension state (a drive) that motivates an organism to satisfy the need. deliberate social exclusion of individuals or groups. a complex behavior that is rigidly patterned throughout a species and is unlearned. the principle that performance increases with arousal only up to a point, beyond which performance decreases. Maslow's pyramid of human needs, beginning at the base with physiological needs that must first be satisfied before higher- the need to build relationships and to feel part of a group. in psychology, passion and perseverance in the pursuit of long- a tendency to maintain a balanced or constant internal state; the regulation of any aspect of body chemistry, such as blood glucose, around a particular level. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 10.1

1. Today's evolutionary psychology shares an idea that was an underlying assumption of instinct theory. That idea is that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 10.2

2. An example of a physiological need is ________. An example of a psychological drive is ________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 10.3

3. Jan walks into a friend's kitchen, smells cookies baking, and begins to feel very hungry. The smell of baking cookies is a(n) (incentive/drive).

Question 10.4

4. theory attempts to explain behaviors that do NOT reduce physiological needs.

Question 10.5

5. With a challenging task, such as taking a difficult exam, performance is likely to peak when arousal is

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 10.6

6. According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, our most basic needs are physiological, including the need for food and water; just above these are ________ needs.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 10.7

7. Which of the following is NOT part of the evidence presented to support the view that humans are strongly motivated by a need to belong?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 10.8

8. What are some ways to manage our social networking time successfully?

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.