9.1 Thinking

Concepts

9-

cognition all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating.

concept a mental grouping of similar objects, events, ideas, or people.

Psychologists who study cognition focus on the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating information. One of these activities is forming concepts—mental groupings of similar objects, events, ideas, and people. The concept chair includes many items—

Concepts simplify our thinking. Imagine life without them. We would need a different name for every event, object, and idea. We could not ask a child to “throw the ball” because there would be no concept of throw or ball. Instead of saying, “They were angry,” we would have to describe expressions, intensities, and words. Concepts such as ball and anger give us much information with little cognitive effort.

prototype a mental image or best example of a category. Matching new items to a prototype provides a quick and easy method for sorting items into categories (as when comparing feathered creatures to a prototypical bird, such as a robin).

We often form our concepts by developing a prototype—a mental image or best example of a category (Rosch, 1978). People more quickly agree that “a robin is a bird” than that “a penguin is a bird.” For most of us, the robin is the birdier bird; it more closely resembles our bird prototype. For people in multiethnic Germany, Caucasian Germans are more prototypically German (Kessler et al., 2010). And the more closely something matches our prototype of a concept—

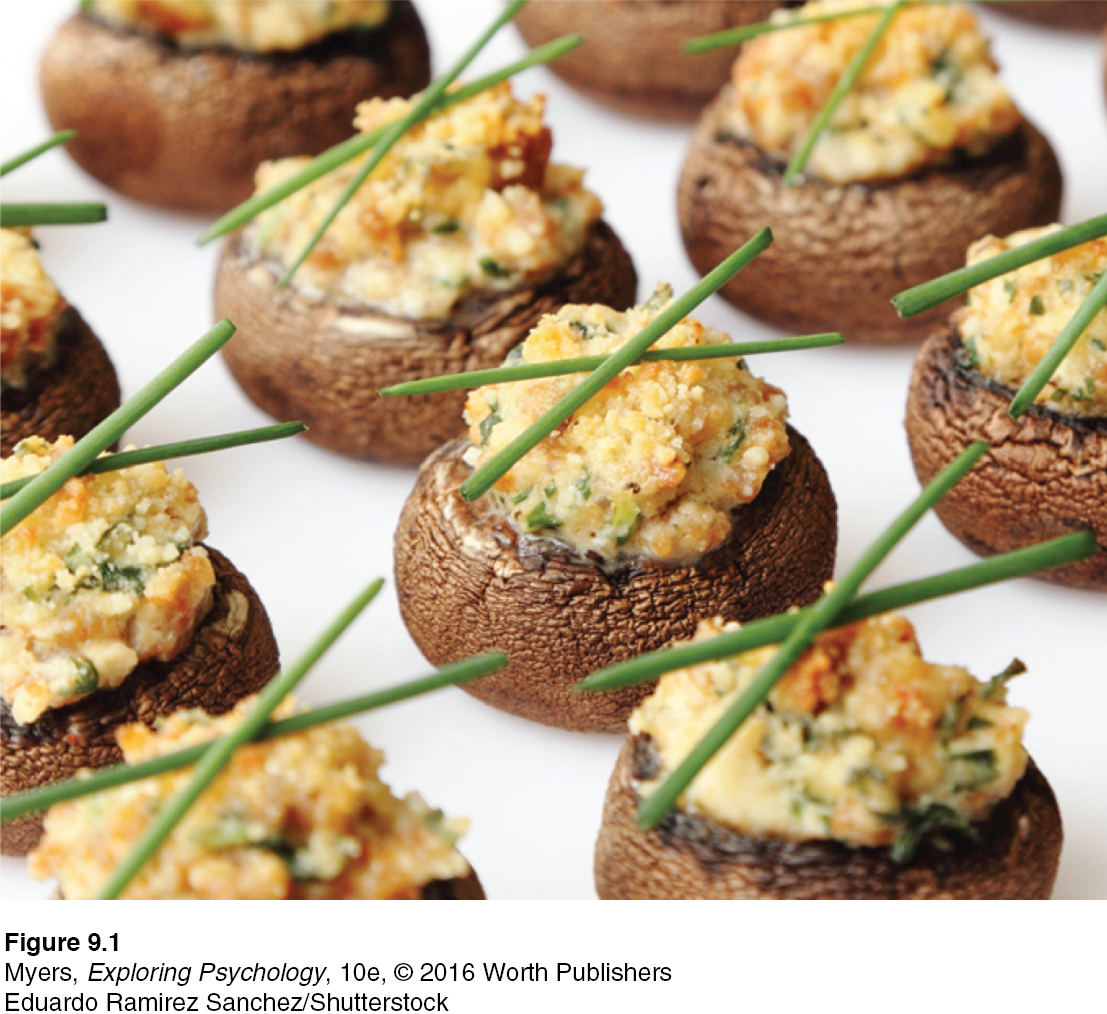

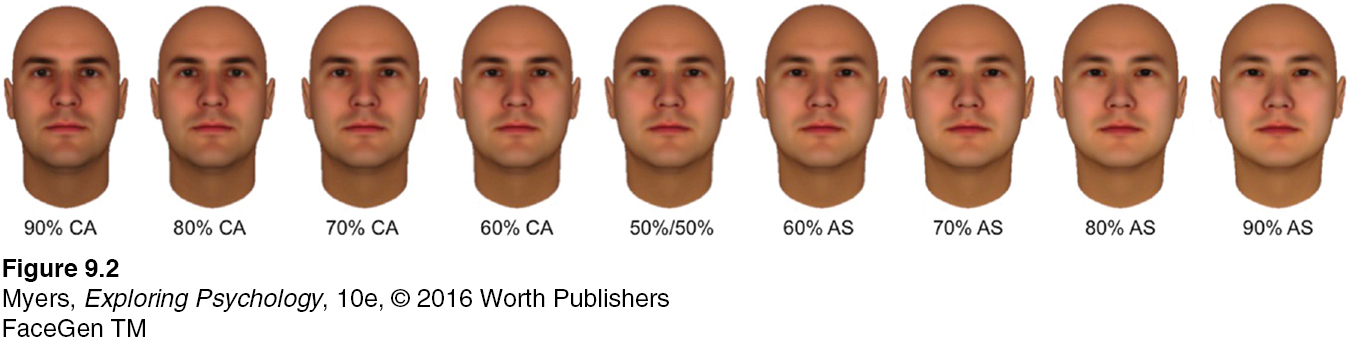

Once we place an item in a category, our memory of it later shifts toward the category prototype, as it did for Belgian students who viewed ethnically blended faces. When viewing a blended face in which 70 percent of the features were Caucasian and 30 percent were Asian, the students categorized the face as Caucasian (FIGURE 9.2). Later, as their memory shifted toward the Caucasian prototype, they were more likely to remember an 80 percent Caucasian face than the 70 percent Caucasian face they had actually seen (Corneille et al., 2004). Likewise, if shown a 70 percent Asian face, they later remembered a more prototypically Asian face. So, too, with gender: People who viewed 70 percent male faces categorized them as male (no surprise there) and then later misremembered them as even more prototypically male (Huart et al., 2005).

Move away from our prototypes, and category boundaries may blur. Is a tomato a fruit? Is a 17-

Problem Solving: Strategies and Obstacles

9-

One tribute to our rationality is our problem-

algorithm a methodical, logical rule or procedure that guarantees solving a particular problem. Contrasts with the usually speedier but also more error-

heuristic a simple thinking strategy that often allows us to make judgments and solve problems efficiently; usually speedier but also more error-

Some problems we solve through trial and error. Thomas Edison tried thousands of light bulb filaments before stumbling upon one that worked. For other problems, we use algorithms, step-

insight a sudden realization of a problem’s solution; contrasts with strategy-

Sometimes we puzzle over a problem and the pieces suddenly fall together in a flash of insight—an abrupt, true-

Teams of researchers have identified brain activity associated with sudden flashes of insight (Kounios & Beeman, 2009; Sandkühler & Bhattacharya, 2008). They gave people a problem: Think of a word that will form a compound word or phrase with each of three other words in a set (such as pine, crab, and sauce), and press a button to sound a bell when you know the answer. (If you need a hint: The word is a fruit.2) EEGs or fMRIs (functional MRIs) revealed the problem solvers’ brain activity. In the first experiment, about half the solutions arrived through a sudden Aha! insight. Before the Aha! moment, the problem solvers’ frontal lobes (which are involved in focusing attention) were active. At the instant of discovery, there was a burst of activity in the right temporal lobe, just above the ear (FIGURE 9.3 below).

Insight strikes suddenly, with no prior sense of “getting warmer” or feeling close to a solution (Knoblich & Oellinger, 2006; Metcalfe, 1986). When the answer pops into mind (apple!), we feel a happy sense of satisfaction. The joy of a joke may similarly lie in our sudden comprehension of an unexpected ending or a double meaning: “You don’t need a parachute to skydive. You only need a parachute to skydive twice.” Groucho Marx was a master at this: “I once shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I’ll never know.”

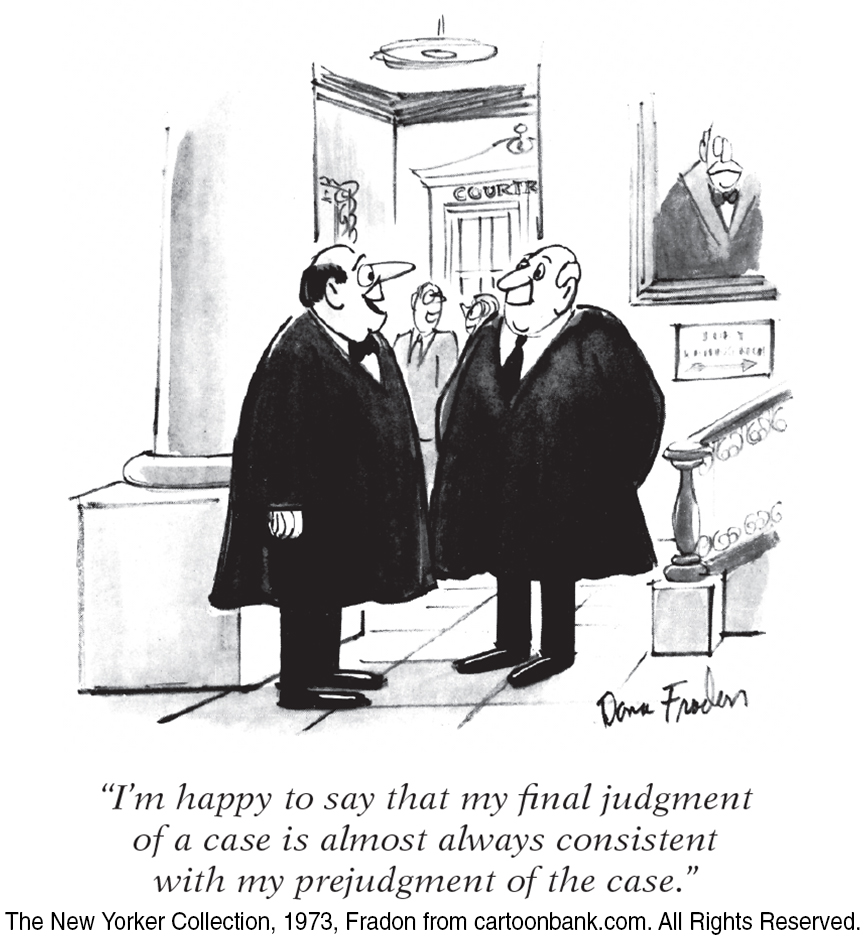

confirmation bias a tendency to search for information that supports our preconceptions and to ignore or distort contradictory evidence.

Insightful as we are, other cognitive tendencies may lead us astray. For example, we more eagerly seek out and favor evidence that supports our ideas than evidence that refutes them (Klayman & Ha, 1987; Skov & Sherman, 1986). In a classic experiment, Peter Wason (1960) demonstrated this tendency, known as confirmation bias, by giving British university students the three-

“Ordinary people,” said Wason (1981), “evade facts, become inconsistent, or systematically defend themselves against the threat of new information relevant to the issue.” Thus, once people form a belief—

“The human understanding, when any proposition has been once laid down . . . forces everything else to add fresh support and confirmation.”

Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, 1620

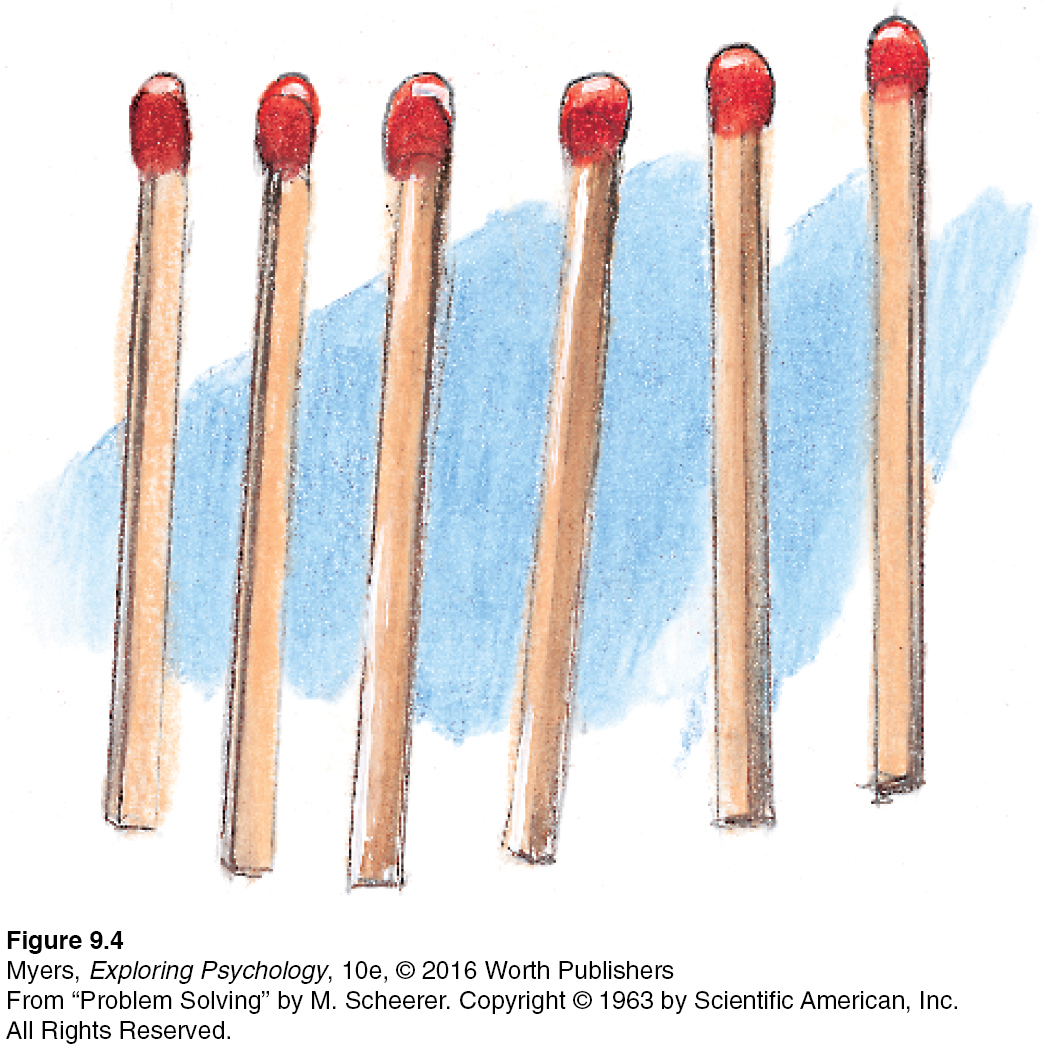

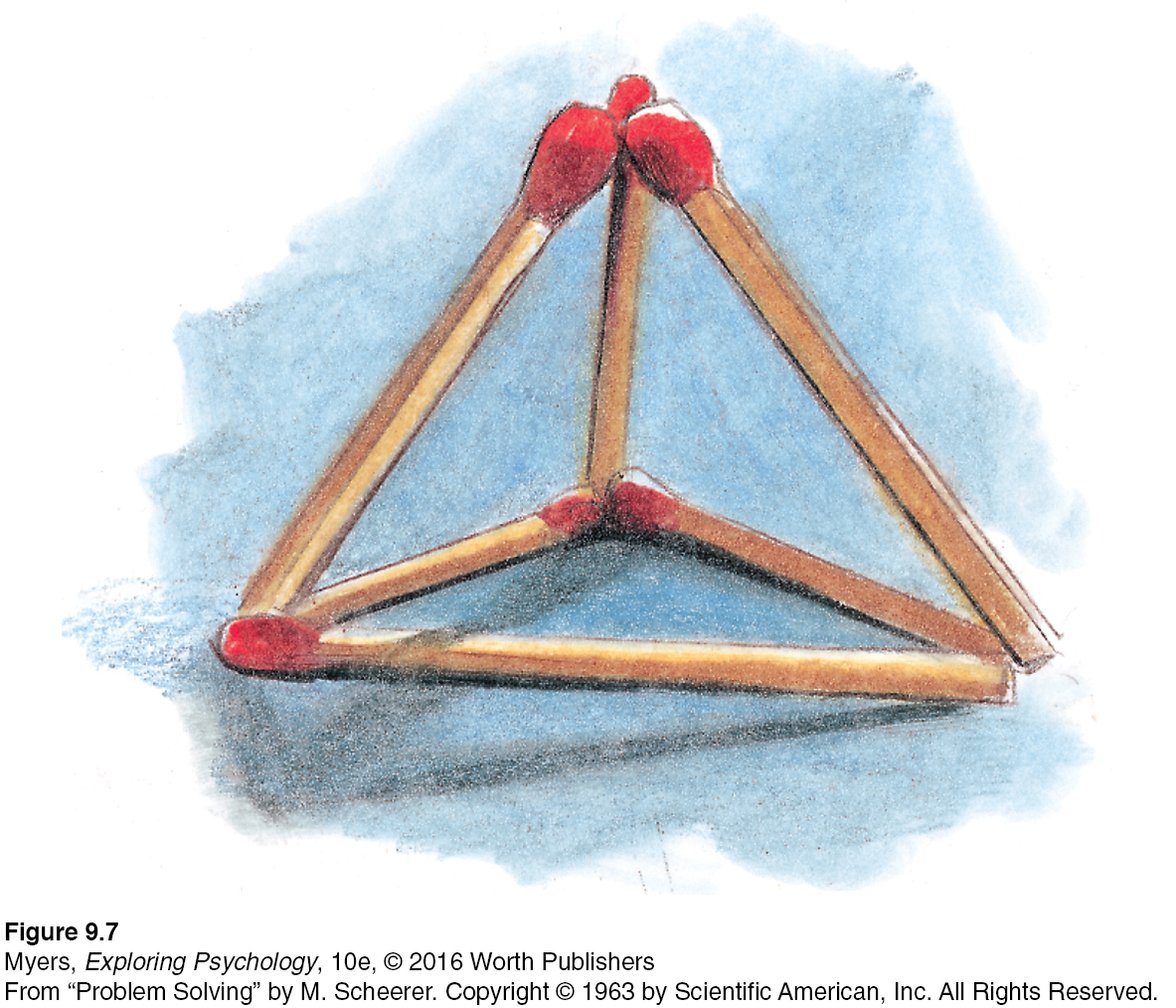

Once we incorrectly represent a problem, it’s hard to restructure how we approach it. If the solution to the matchstick problem in FIGURE 9.4 eludes you, you may be experiencing fixation—an inability to see a problem from a fresh perspective. (For the solution, see FIGURE 9.7.)

mental set a tendency to approach a problem in one particular way, often a way that has been successful in the past.

A prime example of fixation is mental set, our tendency to approach a problem with the mind-

Given the sequence O-

Most people have difficulty recognizing that the three final letters are F(ive), S(ix), and S(even). But solving this problem may make the next one easier:

Given the sequence J-

As a perceptual set predisposes what we perceive, a mental set predisposes how we think; sometimes this can be an obstacle to problem solving, as when our mental set from our past experiences with matchsticks predisposes us to arrange them in two dimensions. To suppress these impediments to our natural creativity, researchers have used electrical stimulation to decrease left hemisphere activity and to increase right hemisphere activity (associated with novel thinking). The result was improved insight, less restrained by the assumptions created by past experience (Chi & Snyder, 2011).

Forming Good and Bad Decisions and Judgments

9-

intuition an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning.

When making each day’s hundreds of judgments and decisions (Should I take a jacket? Can I trust this person? Should I shoot the basketball or pass to the player who’s hot?), we seldom take the time and effort to reason systematically. We just follow our intuition—our fast, automatic, unreasoned feelings and thoughts. After interviewing policy makers in government, business, and education, social psychologist Irving Janis (1986) concluded that they “often do not use a reflective problem-

The Availability Heuristic

availability heuristic estimating the likelihood of events based on their availability in memory; if instances come readily to mind (perhaps because of their vividness), we presume such events are common.

When we need to act quickly, the mental shortcuts we call heuristics enable snap judgments. Thanks to our mind’s automatic information processing, intuitive judgments are instantaneous. They also are usually effective (Gigerenzer & Sturm, 2012). However, research by cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) showed how these generally helpful shortcuts can lead even the smartest people into dumb decisions.3 The availability heuristic operates when we estimate the likelihood of events based on how mentally available they are—

“Kahneman and his colleagues and students have changed the way we think about the way people think.”

American Psychological Association President Sharon Brehm, 2007

The availability heuristic colors our judgments of other people, too. Anything that makes information pop into mind—

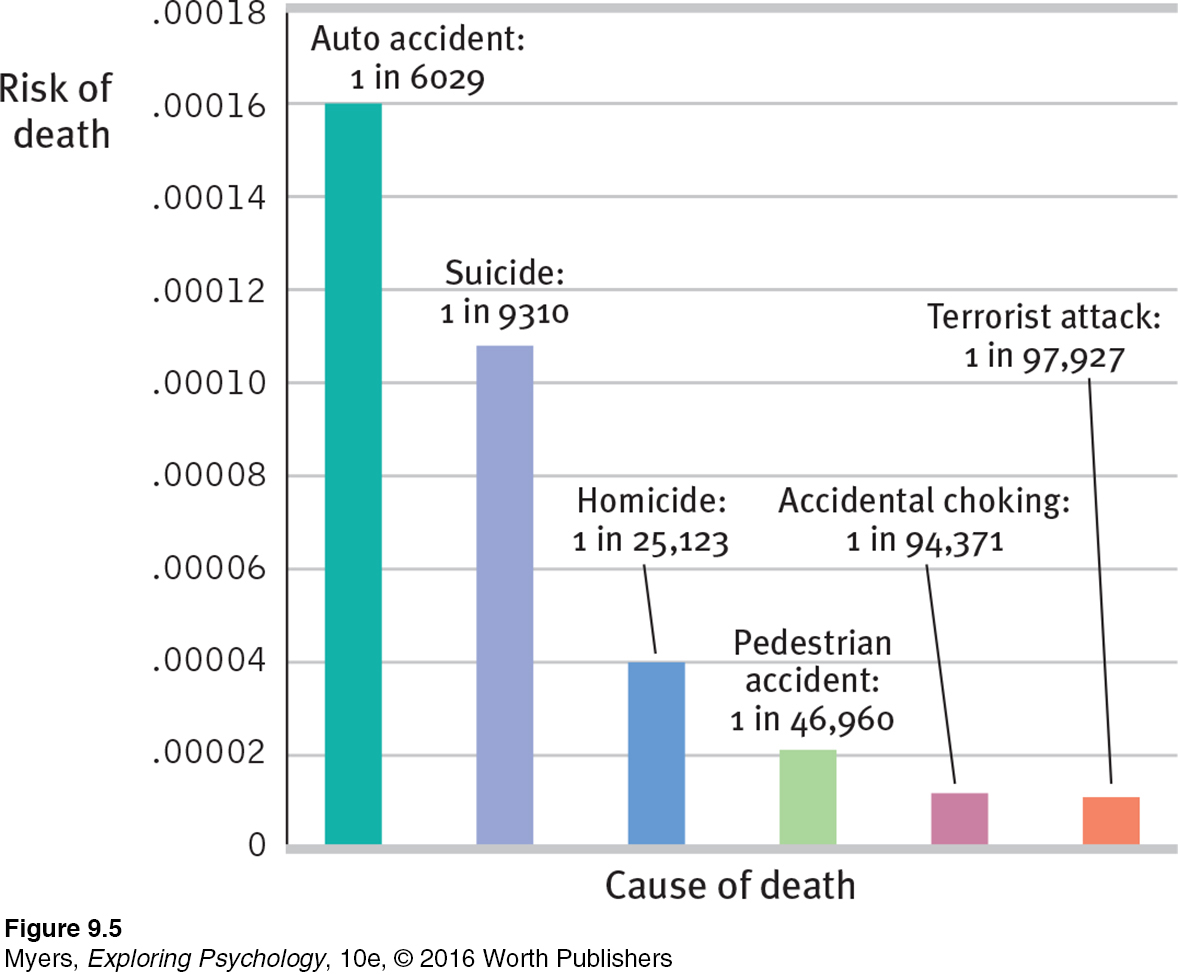

Even during that horrific year, terrorist acts claimed comparatively few lives. Yet when the statistical reality of greater dangers (see FIGURE 9.5) was pitted against the 9/11 terror, the memorable case won: Emotion-

Although our fears often protect us, we sometimes fear the wrong things. (See Thinking Critically About: The Fear Factor below.) We fear flying because we visualize air disasters. We fear letting our sons and daughters walk to school because we see mental snapshots of abducted and brutalized children. We fear swimming in ocean waters because we replay Jaws with ourselves as victims. Even passing by a person who sneezes and coughs can heighten our perceptions of various health risks (Lee et al., 2010). And so, thanks to such readily available images, we come to fear extremely rare events.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

The Fear Factor—

9-

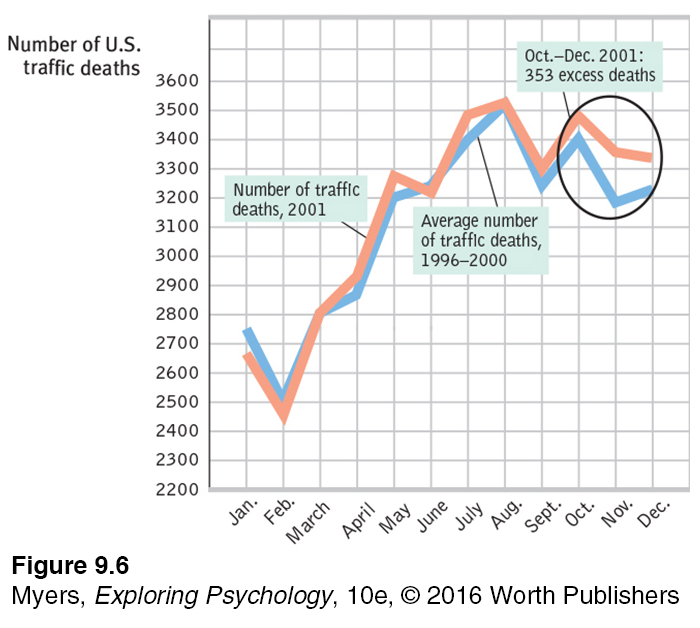

After the 9/11 attacks, many people feared flying more than driving. In a 2006 Gallup survey, only 40 percent of Americans reported being “not afraid at all” to fly. Yet from 2009 to 2011, Americans were—

In a late 2001 essay, I [DM] calculated that if—

Why do we in so many ways fear the wrong things? Why do so many American parents fear school shootings, when their child is more likely to be killed by lightning (Ripley, 2013)? Why, in 2014, were so many Americans more frightened of Ebola (which killed no one who contracted it in the United States) than of influenza, which kills some 24,000 Americans annually? Psychologists have identified four influences that feed fear and cause us to ignore higher risks:

We fear what our ancestral history has prepared us to fear. Human emotions were road tested in the Stone Age. Our old brain prepares us to fear yesterday’s risks: snakes, lizards, and spiders (which combined now kill a tiny fraction of the number killed by modern-

day threats, such as cars and cigarettes). Yesterday’s risks also prepare us to fear confinement and heights, and therefore flying. We fear what we cannot control. Driving we control; flying we do not.

We fear what is immediate. The dangers of flying are mostly telescoped into the moments of takeoff and landing. The dangers of driving are diffused across many moments, each trivially dangerous.

Thanks to the availability heuristic, we fear what is most readily available in memory. Vivid images, like that of a horrific air crash, feed our judgments of risk. Shark attacks kill about one American per year, while heart disease kills 800,000—

but it’s much easier to visualize a shark bite, and thus many people fear sharks more than cigarettes or the effects of an unhealthy diet (Daley, 2011). Similarly, we remember (and fear) widespread disasters (hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes) that kill people dramatically, in bunches. But we fear too little the less dramatic threats that claim lives quietly, one by one, continuing into the distant future. Horrified citizens and commentators renewed calls for U.S. gun control in 2015, after nine African- Americans at a Bible study were slain by a racist guest— although guns kill about 30 Americans every day, one by one, in a less dramatic fashion. Philanthropist Bill Gates has noted that each year, a half- million children worldwide die from rotavirus. This is the equivalent of four 747s full of children every day, and we hear nothing of it (Glass, 2004). Media outlets often draw readers and viewers by reporting on the immediate and the dramatic. “If it bleeds, it leads.”

The news, and our own memorable experiences, can make us disproportionately fearful of infinitesimal risks—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why can news be described as “something that hardly ever happens”? How does knowing this help us assess our fears?

“Fearful people are more dependent, more easily manipulated and controlled, more susceptible to deceptively simple, strong, tough measures and hard-

Media researcher George Gerbner to U.S. Congressional Subcommittee on Communications, 1981

Meanwhile, the lack of available images of future climate change disasters—

"Don’t believe everything you think."

Bumper sticker

“Global warming isn’t real because it was cold today! Also great news: World hunger is over because I just ate.”

Stephen Colbert tweet, November 18, 2014

Dramatic outcomes make us gasp; probabilities we hardly grasp. As of 2013, some 40 nations have sought to harness the positive power of vivid, memorable images by putting eye-

Overconfidence

overconfidence the tendency to be more confident than correct—

Sometimes our judgments and decisions go awry simply because we are more confident than correct. Across various tasks, people overestimate their performance (Metcalfe, 1998). If 60 percent of people correctly answer a factual question, such as “Is absinthe a liqueur or a precious stone?,” they will typically average 75 percent confidence (Fischhoff et al., 1977). (It’s a licorice-

It was an overconfident BP that, before its exploded drilling platform spewed oil into the Gulf of Mexico, downplayed safety concerns, and then downplayed the spill’s magnitude (Mohr et al., 2010; Urbina, 2010). It is overconfidence that drives stockbrokers and investment managers to market their ability to outperform stock market averages (Malkiel, 2012). A purchase of stock X, recommended by a broker who judges this to be the time to buy, is usually balanced by a sale made by someone who judges this to be the time to sell. Despite their confidence, buyer and seller cannot both be right.

Hofstadter’s Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid, 1979

“When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it; this is knowledge.”

Confucius (551-

Overconfidence can also feed extreme political views. People with a superficial understanding of proposals for cap-

Classrooms are full of overconfident students who expect to finish assignments and write papers ahead of schedule (Buehler et al., 1994, 2002). In fact, these projects generally take about twice the number of days predicted. This “planning fallacy” (underestimating the time and cost of a project) routinely occurs with construction projects, which often finish late and over budget.

Overconfidence can have adaptive value. People who err on the side of overconfidence live more happily. Their seeming competence can help them gain influence (Anderson et al., 2012). Moreover, given prompt and clear feedback, as weather forecasters receive after each day’s predictions, we can learn to be more realistic about the accuracy of our judgments (Fischhoff, 1982). The wisdom to know when we know a thing and when we do not is born of experience.

Belief Perseverance

belief perseverance clinging to one’s initial conceptions after the basis on which they were formed has been discredited.

Our overconfidence is startling. Equally so is our belief perseverance—our tendency to cling to our beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. One study of belief perseverance engaged people with opposing views of capital punishment (Lord et al., 1979). After studying two supposedly new research findings, one supporting and the other refuting the claim that the death penalty deters crime, each side was more impressed by the study supporting its own beliefs. And each readily disputed the other study. Thus, showing the pro-

To rein in belief perseverance, a simple remedy exists: Consider the opposite. When the same researchers repeated the capital-

The more we come to appreciate why our beliefs might be true, the more tightly we cling to them. Once beliefs form and get justified, it takes more compelling evidence to change them than it did to create them. Prejudice persists. Beliefs often persevere.

The Effects of Framing

framing the way an issue is posed; how an issue is framed can significantly affect decisions and judgments.

Framing—the way we present an issue—

Framing can be a powerful persuasion tool. Carefully posed options can nudge people toward decisions that could benefit them or society as a whole (Benartzi & Thaler, 2013; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008):

Encouraging citizens to be organ donors. In many European countries as well as the United States, those renewing their driver’s license can decide whether they want to be organ donors. In some countries, the default option is Yes, but people can opt out. Nearly 100 percent of the people in opt-

out countries have agreed to be donors. In the United States, Britain, and Germany, the default option is No, but people can opt in. In these countries, less than half have agreed to be donors (Hajhosseini et al., 2013; Johnson & Goldstein, 2003). Nudging employees to save for their retirement. A 2006 U.S. pension law recognized the framing effect. Before that law, employees who wanted to contribute to a retirement plan typically had to choose a lower take-

home pay, which few people will do. Companies can now automatically enroll their employees in the plan but allow them to opt out. Under the new voluntary opt- out arrangement, enrollments in one analysis of 3.4 million workers soared from 59 to 86 percent (Rosenberg, 2010). Boosting student morale: When 70 percent on an exam feels better than 72 percent. One economist’s students were upset by a “hard” exam, on which they averaged 72 out of 100. So on the next exam, he made the highest possible score 137 points. Although the class average score of 96 was only 70 percent correct, “the students were delighted” (a numerical 96 felt so much better than 72). So he continued the reframed exam results thereafter (Thaler, 2015).

The point to remember: Those who understand the power of framing can use it (for good or ill) to nudge our decisions.

The Perils and Powers of Intuition

9-

The perils of intuition—

Throughout this book you will see examples of smart intuition. In brief,

Intuition is analysis “frozen into habit” (Simon, 2001). It is implicit knowledge—

what we’ve learned and recorded in our brains but can’t fully explain (Chassy & Gobet, 2011; Gore & Sadler- Smith, 2011). Chess masters display this tacit expertise in “blitz chess,” where, after barely a glance, they intuitively know the right move (Burns, 2004). We see this expertise in the smart and quick judgments of experienced nurses, firefighters, art critics, car mechanics, and musicians. Skilled athletes can react without thinking. Indeed, conscious thinking may disrupt well- practiced movements such as batting or shooting free throws. For all of us who have developed some special skill, what feels like instant intuition is actually an acquired ability to perceive and react in an eyeblink. Intuition is usually adaptive, enabling quick reactions. Our fast and frugal heuristics let us intuitively assume that fuzzy looking objects are far away—

which they usually are, except on foggy mornings. Seeing a stranger who looks like someone who has harmed or threatened us in the past, we may automatically react warily. Newlyweds’ automatic associations— their gut reactions— to their new spouses likewise predict their future marital happiness (McNulty et al., 2013). Our learned associations surface as gut feelings. Page 324Intuition flows from unconscious processing. Today’s cognitive science offers many examples of unconscious automatic influences on our judgments (Custers & Aarts, 2010). Consider: Most people guess that the more complex the choice, the smarter it is to make decisions rationally rather than intuitively (Inbar et al., 2010). Actually, Dutch psychologists have shown that in making complex decisions, we benefit by letting our brain work on a problem without consciously thinking about it (Strick et al., 2010, 2011). In one series of experiments, three groups of people read complex information (for example, about apartments or soccer matches). The first group’s participants stated their preference immediately after reading information about four possible options. The second group, given several minutes to analyze the information, made slightly smarter decisions. But wisest of all, in several studies, was the third group, whose attention was distracted for a time, enabling their minds to engage in automatic, unconscious processing of the complex information. The practical lesson: Letting a problem “incubate” while we attend to other things can pay dividends (Sio & Ormerod, 2009). Facing a difficult decision involving lots of facts, we’re wise to gather all the information we can, and then say, “Give me some time not to think about this.” By taking time to sleep on it, we let our unconscious mental machinery work. Thanks to our active brain, nonconscious thinking (reasoning, problem solving, decision making, planning) is surprisingly astute (Creswell et al., 2013; Hassin, 2013; Lin & Murray, 2015).

Critics note that some studies have not found the supposed power of unconscious thought and remind us that deliberate, conscious thought also furthers smart thinking (Lassiter et al., 2009; Newell, 2015; Nieuwenstein et al., 2015; Payne et al., 2008). In challenging situations, superior decision makers, including chess players, take time to think (Moxley et al., 2012). And with many sorts of problems, deliberative thinkers are aware of the intuitive option, but know when to override it (Mata et al., 2013). Consider:

A bat and a ball together cost 110 cents.

The bat costs 100 cents more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

Most people’s intuitive response—

The bottom line: Our two-

Thinking Creatively

9-

creativity the ability to produce new and valuable ideas.

Creativity is the ability to produce ideas that are both novel and valuable (Hennessey & Amabile, 2010). Consider Princeton mathematician Andrew Wiles’ incredible, creative moment in 1994. Pierre de Fermat, a seventeenth-

Wiles had pondered Fermat’s theorem for more than 30 years and had come to the brink of a solution. One morning, out of the blue, the final “incredible revelation” struck him. “It was so indescribably beautiful; it was so simple and so elegant. I couldn’t understand how I’d missed it. . . . It was the most important moment of my working life” (Singh, 1997, p. 25).

convergent thinking narrowing the available problem solutions to determine the single best solution.

divergent thinking expanding the number of possible problem solutions; creative thinking that diverges in different directions.

Creativity like Wiles’ is supported by a certain level of aptitude (ability to learn). Those who score exceptionally high in quantitative (math) aptitude as 13-

Robert Sternberg and his colleagues believe creativity has five components (Sternberg, 1988, 2003; Sternberg & Lubart, 1991, 1992):

Expertise—well-

developed knowledge— furnishes the ideas, images, and phrases we use as mental building blocks. “Chance favors only the prepared mind,” observed Louis Pasteur. The more blocks we have, the more chances we have to combine them in novel ways. Wiles’ well- developed knowledge put the needed theorems and methods at his disposal. Imaginative thinking skills provide the ability to see things in novel ways, to recognize patterns, and to make connections. Having mastered a problem’s basic elements, we redefine or explore it in a new way. Wiles’ imaginative solution combined two partial solutions.

A venturesome personality seeks new experiences, tolerates ambiguity and risk, and perseveres in overcoming obstacles. Wiles said he labored in near-

isolation from the mathematics community partly to stay focused and avoid distraction. Such determination is an enduring trait. Intrinsic motivation is the quality of being driven more by interest, satisfaction, and challenge than by external pressures (Amabile & Hennessey, 1992). Creative people focus less on extrinsic motivators—

meeting deadlines, impressing people, or making money— than on the pleasure and stimulation of the work itself. As Wiles noted, “I was so obsessed by this problem that . . . I was thinking about it all the time— [from] when I woke up in the morning to when I went to sleep at night” (Singh & Riber, 1997). A creative environment sparks, supports, and refines creative ideas. Wiles stood on the shoulders of others and collaborated with a former student. After studying the careers of 2026 prominent scientists and inventors, Dean Keith Simonton (1992) noted that the most eminent were mentored, challenged, and supported by their colleagues. Creativity-

fostering environments support innovation, team building, and communication (Hülsheger et al., 2009). They also minimize anxiety and foster contemplation (Byron & Khazanchi, 2011). After Jonas Salk solved a problem that led to the polio vaccine while visiting a monastery, he designed the Salk Institute to provide contemplative spaces where scientists could work without interruption (Sternberg, 2006).

For those seeking to boost the creative process, research offers some ideas:

Develop your expertise. Ask yourself what you care about and most enjoy. Follow your passion and become an expert at something.

Allow time for incubation. With enough available knowledge—

the mental building blocks we need to create novel connections— a period of inattention to a problem (“sleeping on it”) allows for automatic processing to form associations (Zhong et al., 2008). So think hard on a problem, then set it aside and come back to it later. Set aside time for the mind to roam freely. Take time away from attention-

absorbing distractions. Creativity springs from “defocused attention” (Simonton, 2012a,b). So jog, go for a long walk, or meditate. Serenity seeds spontaneity. Page 326Experience other cultures and ways of thinking. Living abroad sets the creative juices flowing. Even after controlling for other variables, students who have spent time abroad and embraced their host culture are more adept at working out creative solutions to problems (Lee et al., 2012; Tadmor et al., 2012). Multicultural experiences expose us to multiple perspectives and facilitate flexible thinking, and may also trigger another stimulus for creativity—

a sense of difference from others (Kim et al., 2013; Ritter et al., 2012).

RETRIEVE IT

Match the process or strategy listed below with the description.

Question

Algorithm Intuition Insight Heuristics Fixation Confirmation bias Overconfidence Creativity Framing Belief perseverance | The ability to produce novel and valuable ideas. Ignoring evidence that proves our beliefs are wrong; closes our mind to new ideas. Sudden Aha! reaction that provides instant realization of the solution. Fast, automatic, effortless feelings and thoughts based on our experience; adaptive but can lead us to overfeel and underthink. Simple thinking shortcuts that allow us to act quickly and efficiently, but put us at risk for errors. Tendency to search for support for our own views and ignore contradictory evidence. Inability to view problems from a new angle; focuses thinking but hinders creative problem solving. Overestimating the accuracy of our beliefs and judgments; allows us to be happy and to make decisions easily, but puts us at risk for errors. Methodological rule or procedure that guarantees a solution but requires time and effort. Wording a question or statement so that it evokes a desired response; can influence others' decisions and produce a misleading result. |

Do Other Species Share Our Cognitive Skills?

9-

Other animals are smarter than we often realize. In her 1908 book, The Animal Mind, pioneering psychologist Margaret Floy Washburn explained that animals’ consciousness and intelligence can be inferred from their behavior. In 2012, neuroscientists convening at the University of Cambridge added that animal consciousness can also be inferred from animals’ brains: “Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds,” possess the neural networks “that generate consciousness” (Low et al., 2012). Consider, then, what animal brains can do.

Using Concepts and Numbers

Even pigeons—

Displaying Insight

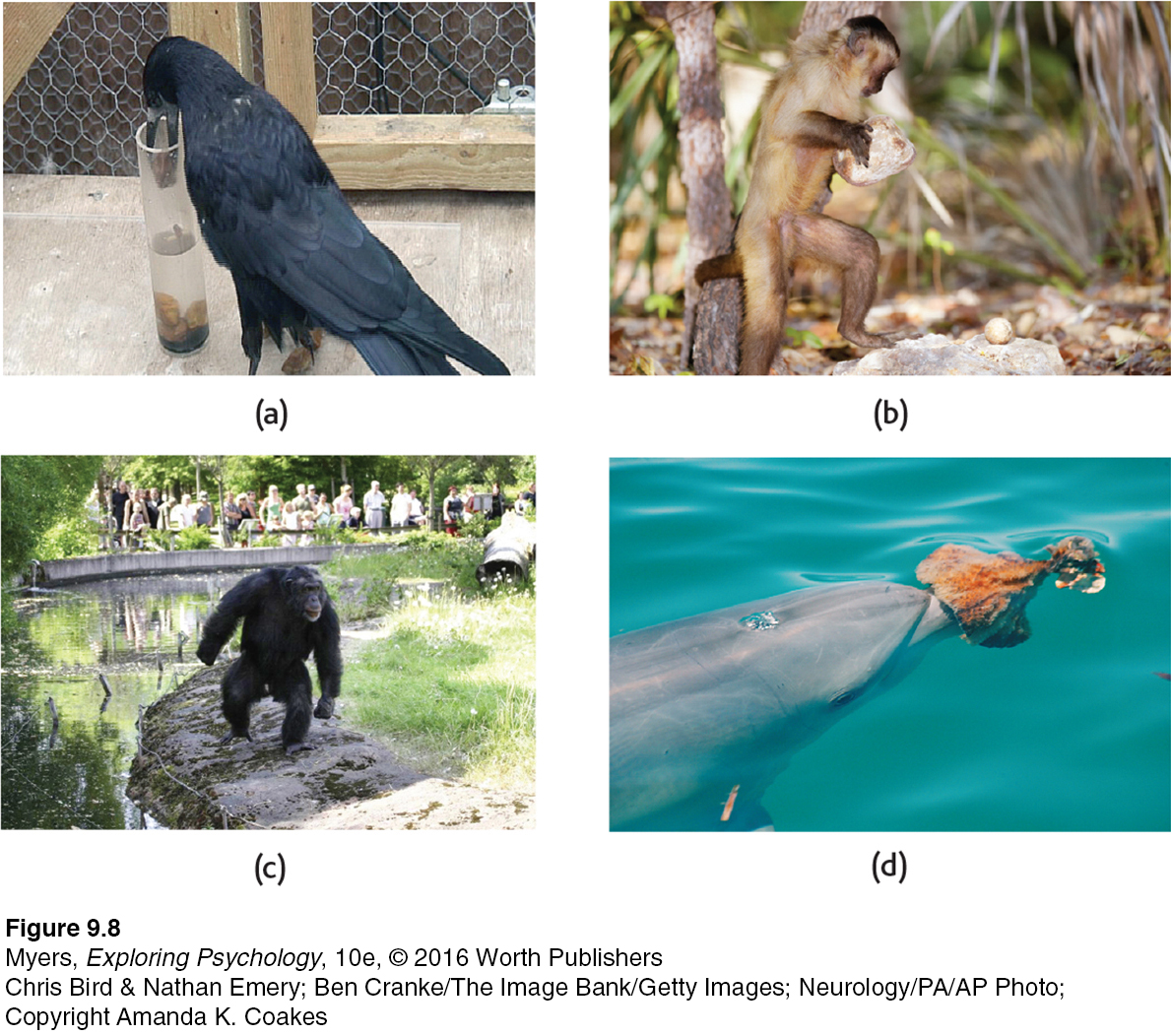

Psychologist Wolfgang Köhler (1925/1957) showed that we are not the only creatures to display insight. He placed a piece of fruit and a long stick outside the cage of a chimpanzee named Sultan, beyond his reach. Inside the cage, he placed a short stick, which Sultan grabbed, using it to try to reach the fruit. After several failed attempts, he dropped the stick and seemed to survey the situation. Then suddenly (as if thinking “Aha!”), Sultan jumped up and seized the short stick again. This time, he used it to pull in the longer stick—

Using Tools and Transmitting Culture

Like humans, many other species invent behaviors and transmit cultural patterns to their observing peers and offspring (Boesch-

Other animals have also shown surprising cognitive talents. In tests, elephants have demonstrated self-

There is no question that other species display many remarkable cognitive skills. But one big question remains: Do they, like humans, exhibit language? First, let’s consider what language is, and how it develops.

* * *

Returning to our debate about how deserving we humans are of our name Homo sapiens, let’s pause to issue an interim report card. On decision making and risk assessment, our error-

REVIEW Thinking

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

9-

Question

9-

Question

9-

Question

9-

Question

9-

Question

9-

Question

9-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

cognition (p. 316) concept (p. 316) prototype (p. 316) algorithm (p. 317) heuristic (p. 317) insight (p. 317) confirmation bias (p. 317) mental set (p. 318) intuition (p. 318) availability heuristic (p. 319) overconfidence (p. 321) belief perseverance (p. 322) framing (p. 322) creativity (p. 322) convergent thinking (p. 325) divergent thinking (p. 325) | a tendency to approach a problem in one particular way, often a way that has been successful in the past. narrowing the available problem solutions to determine the single best solution. an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning. a mental image or best example of a category. Matching new items to a prototype provides a quick and easy method for sorting items into categories (as when comparing feathered creatures to a prototypical bird, such as a robin). the way an issue is posed; how an issue is framed can significantly affect decisions and judgments. a simple thinking strategy that often allows us to make judgments and solve problems efficiently; usually speedier but also more error- a mental grouping of similar objects, events, ideas, or people. a methodical, logical rule or procedure that guarantees solving a particular problem. Contrasts with the usually speedier but also more error- clinging to one's initial conceptions after the basis on which they were formed has been discredited. the tendency to be more confident than correct— the ability to produce new and valuable ideas. a tendency to search for information that supports our preconceptions and to ignore or distort contradictory evidence. a sudden realization of a problem's solution; contrasts with strategy- estimating the likelihood of events based on their availability in memory; if instances come readily to mind (perhaps because of their vividness), we presume such events are common. all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating. expanding the number of possible problem solutions; creative thinking that diverges in different directions. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 9.1

1. A mental grouping of similar things is called a .

Question 9.2

2. The most systematic procedure for solving a problem is a(n) .

Question 9.3

3. Oscar describes his political beliefs as “strongly liberal,” but he has decided to explore opposing viewpoints. How might he be affected by confirmation bias and belief perseverance in this effort?

Question 9.4

4. A major obstacle to problem solving is fixation, which is a(n)

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 9.5

5. Widely reported terrorist attacks, such as on 9/11 in the United States, led some observers to initially assume in 2014 that the missing Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 was probably also the work of terrorists. This assumption illustrates the heuristic.

Question 9.6

6. When consumers respond more positively to ground beef described as “75 percent lean” than to the same product labeled “25 percent fat,” they have been influenced by .

Question 9.7

7. Which of the following is NOT a characteristic of a creative person?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.