3 Government and Institutions: Policies and Performance

Three important things that influence the international macroeconomy:

1. Integration and Capital Controls:

The Regulation of International Finance

There has been a striking trend toward the integration of financial markets; many countries have eliminated or reduced capital controls.

a. Key Topics:

Why have countries permitted capital mobility? What are the benefits of doing so? Why did it not happen before the 1970s? What are the costs? Can capital controls be beneficial?

2. Independence and Monetary Policy:

The Choice of Exchange Rate Regimes

Fixed versus flexible exchange rates is a major policy decision. Fixing the exchange rate may reduce transaction costs, but it also forces a country to abandon an independent monetary policy. Still, fixed rates are attractive enough that some countries have surrendered their own currencies entirely; others have adopted the use of a foreign currency.

a. Key Topics: Why do most countries have their own monies? Why do others adopt a single currency, or use another country’s as their own? Why do some peg? Why do others float?

3. Institutions and Economic Performance:

The Quality of Governance

Legal, political, social, cultural, ethical, and religious aspects of society can affect economic performance. The quality of “governance” is strongly correlated with economic performance. Possible sources of institutional variation include the behavior of colonizing countries, the types of legal code, and resource endowments.

a. Key Topics: Differences in governance affect economic performance. This means that economic policies that work well in well-governed countries may not work as well in poorly-governed countries.

In theory, one could devise a course of study in international economics without reference to government, but the result might not shed much light on reality. As we know from other courses in economics, and as we have already started to see in this chapter, government actions influence economic outcomes in many ways by making decisions about exchange rates, macroeconomic policies, whether to pay (or not pay) their debts, and so on.

To gain a deeper understanding of the global macroeconomy, we can look at government activity on several distinct levels. We will study policies, direct government actions, including familiar textbook topics like monetary and fiscal policy. However, economists also consider the broader context of rules and norms, or the regimes in which policy choices are made. At the broadest level, research also focuses on institutions, a term that refers to the overall legal, political, cultural, and social structures that influence economic and political actions.

Make a list of the three things the government can do.

To conclude this brief introduction to international macroeconomics, we highlight three important features of the broad macroeconomic environment that play an important role in the remainder of this book: the rules that a government decides to apply to restrict or allow capital mobility; the decision that a government makes between a fixed and a floating exchange rate regime; and the institutional foundations of economic performance, such as the quality of governance that prevails in a country.

Integration and Capital Controls: The Regulation of International Finance

The United States is seen as one of the most financially open countries in the world, fully integrated into the global capital market. This is mostly true, but in recent years the U.S. government has blocked some foreign investment in ports, oil, and airlines. These are exceptional cases in the United States, but in many countries there are numerous, severe restrictions on cross-border financial transactions.

It is important to remember that globalization does not occur in a political vacuum. Globalization is often viewed as a technological phenomenon, a process driven by innovations in transport and communications such as container shipping and the Internet. But international economic integration has also occurred because some governments have allowed it to happen. In the past 60 years, international trade has grown as trade barriers have been slowly dismantled. More recently, many nations have encouraged international capital movement by lifting restrictions on financial transactions.

The stylized facts

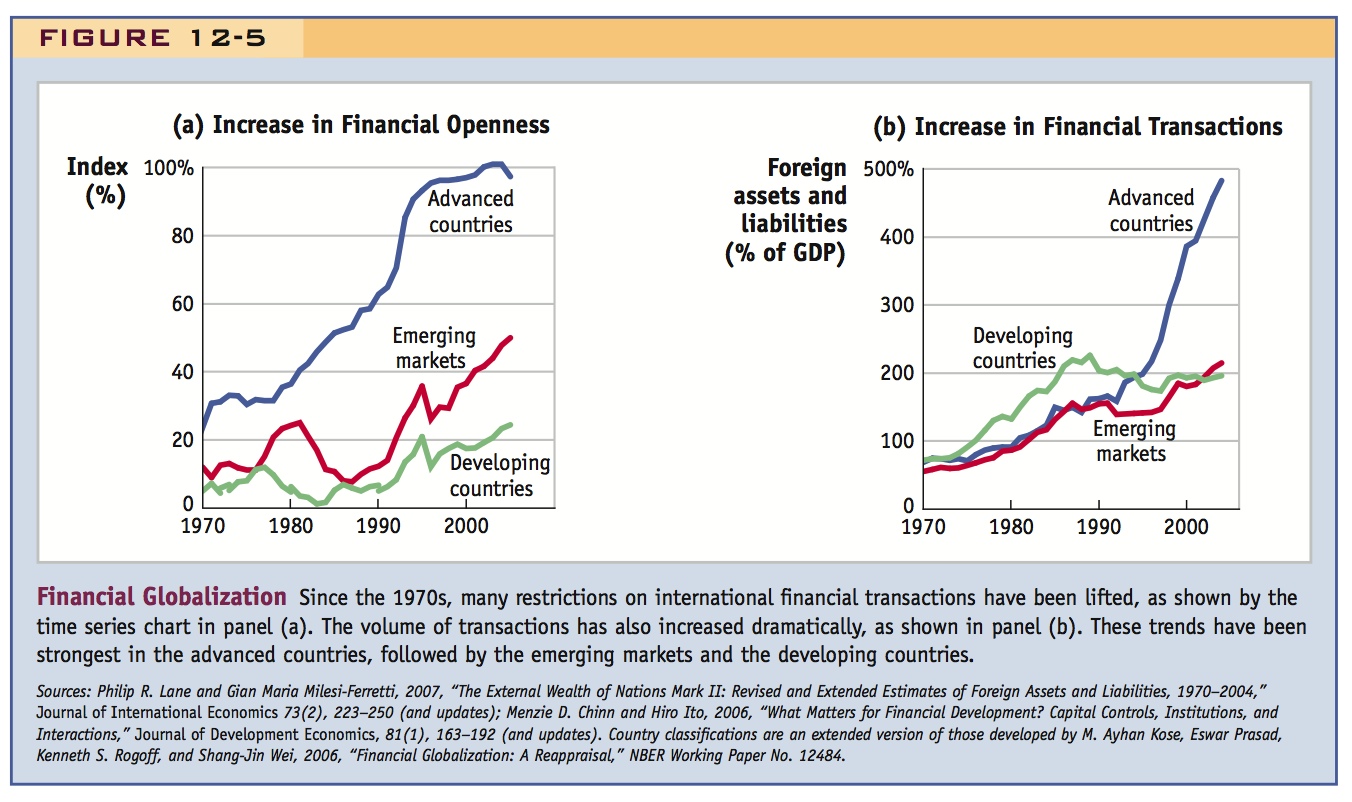

Figure 12-5 documents some of the important features of the trend toward financial globalization since 1970. Panel (a) employs an index of financial openness, where 0% means fully closed with tight capital controls and 100% means fully open with no controls. The index is compiled from measures of restriction on cross-border financial transactions. The average value of the index is shown for three groups of countries that will play an important role in our analysis:

- Advanced countries—countries with high levels of income per person that are well integrated into the global economy

- Emerging markets—middle-income countries that are growing and becoming more integrated into the global economy

- Developing countries—low-income countries that are not yet well integrated into the global economy

15

Using these data to gauge policy changes over the past three decades, we can see that the trend toward financial openness started first, and went the furthest, in the advanced countries, with a rapid shift toward openness evident in the 1980s, when many countries abolished capital controls that had been in place since World War II. We can also see that in the 1990s, emerging markets also started to become more financially open and, to a lesser degree, so did some developing countries.

What were the consequences of these policy changes? Panel (b) shows that as the world became more financially open, the extent of cross-border financial transactions (total foreign assets and liabilities expressed as a fraction of output) increased by a factor of 10 or more. As one might expect, this trend has gone the furthest in the more financially open advanced countries, but the emerging markets and developing countries follow a similar path.

Key Topics Why have so many countries made the choice to pursue policies of financial openness? What are the potential economic benefits of removing capital controls and encouraging openness? If there are benefits, why has this policy change been so slow to occur since the 1970s? Are there any costs that offset the benefits? If so, can capital controls benefit the country that imposes them?

16

Independence and Monetary Policy: The Choice of Exchange Rate Regimes

Say that there are intermediate regimes that we will discuss later. Also intimate that financial integration will have important implications for the choice of exchange rate regime.

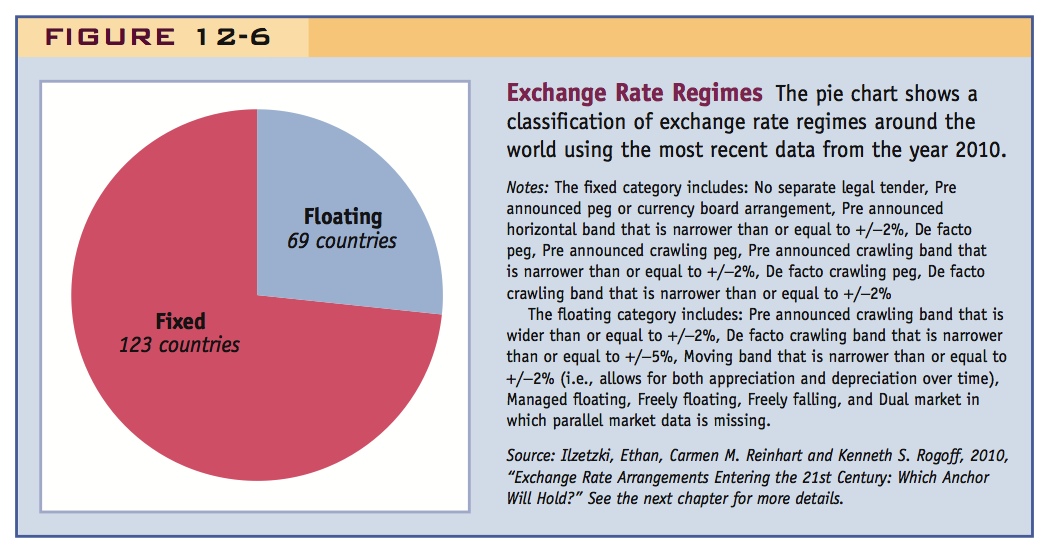

There are two broad categories of exchange rate behavior: fixed regimes and floating regimes. How common is each type? Figure 12-6 shows that there are many countries operating under each kind of regime. Because fixed and floating are both common regime choices, we have to understand both.

The choice of exchange rate regime is a major policy problem. If you have noticed the attention given by journalists and policy makers in recent years to the exchange rate movements of the dollar, euro, yen, pound, yuan, and other currencies, you know that these are important issues in debates on the global economy.

Exploring the evidence on exchange rate fluctuations, their origins, and their impact is a major goal of this book. On an intuitive level, whether we are confused travelers fumbling to change money at the bank or importers and exporters trying to conduct business in a predictable way, we have a sense that exchange rate fluctuations, especially if drastic, can impose real economic costs. If every country fixed its exchange rate, we could avoid those costs. Or, taking the argument to an extreme, if we had a single world currency, we might think that all currency-related transaction costs could be avoided. With more than 150 different currencies in existence today, however, we are very far from such a monetary utopia!

The existence of multiple currencies in the world dates back centuries, and for a country to possess its own currency has long been viewed as an almost essential aspect of sovereignty. Without control of its own national currency, a government’s freedom to pursue its own monetary policy is sacrificed automatically. However, it still remains to be seen how beneficial monetary independence is.

Tell students to think of a common currency as an extreme form of fixed rates: The 12 Federal Reserve banks issue dollars with their names attached that can be interpreted as different currencies with a rigidly fixed exchange rate of one.

Despite the profusion of currencies, we also see newly emerging forms of monetary organization. Some groups of countries have sought to simplify their transactions through the adoption of a common currency with shared policy responsibility. The most notable example is the Eurozone, a subset of the European Union that in 2013 comprised 17 countries, but with more members expected to join at some point in the future. Still other countries have chosen to use currencies over which they have no policy control, as with the recent cases of dollarization in El Salvador and Ecuador.

17

Key Topics Why do so many countries insist on the “barbarism” of having their own currency (as John Stuart Mill put it)? Why do some countries create a common currency or adopt another nation’s currency as their own? Why do some of the countries that have kept their own currencies maintain a fixed exchange rate with another currency? And why do others permit their exchange rate to fluctuate over time, making a floating exchange rate their regime choice?

Institutions and Economic Performance: The Quality of Governance

This is all certainly true, and students will enjoy talking about it. However, understanding these issues really takes us beyond the range of the book. For our purposes here the quality of governance (or lack of it) just intrudes as an exogenous factor that impinges upon macroeconomic outcomes.

Going beyond specific policy choices, economists also consider the broader institutional context in which such choices are made. The legal, political, social, cultural, ethical, and religious structures of a society can influence the environment for economic prosperity and stability, or poverty and instability.

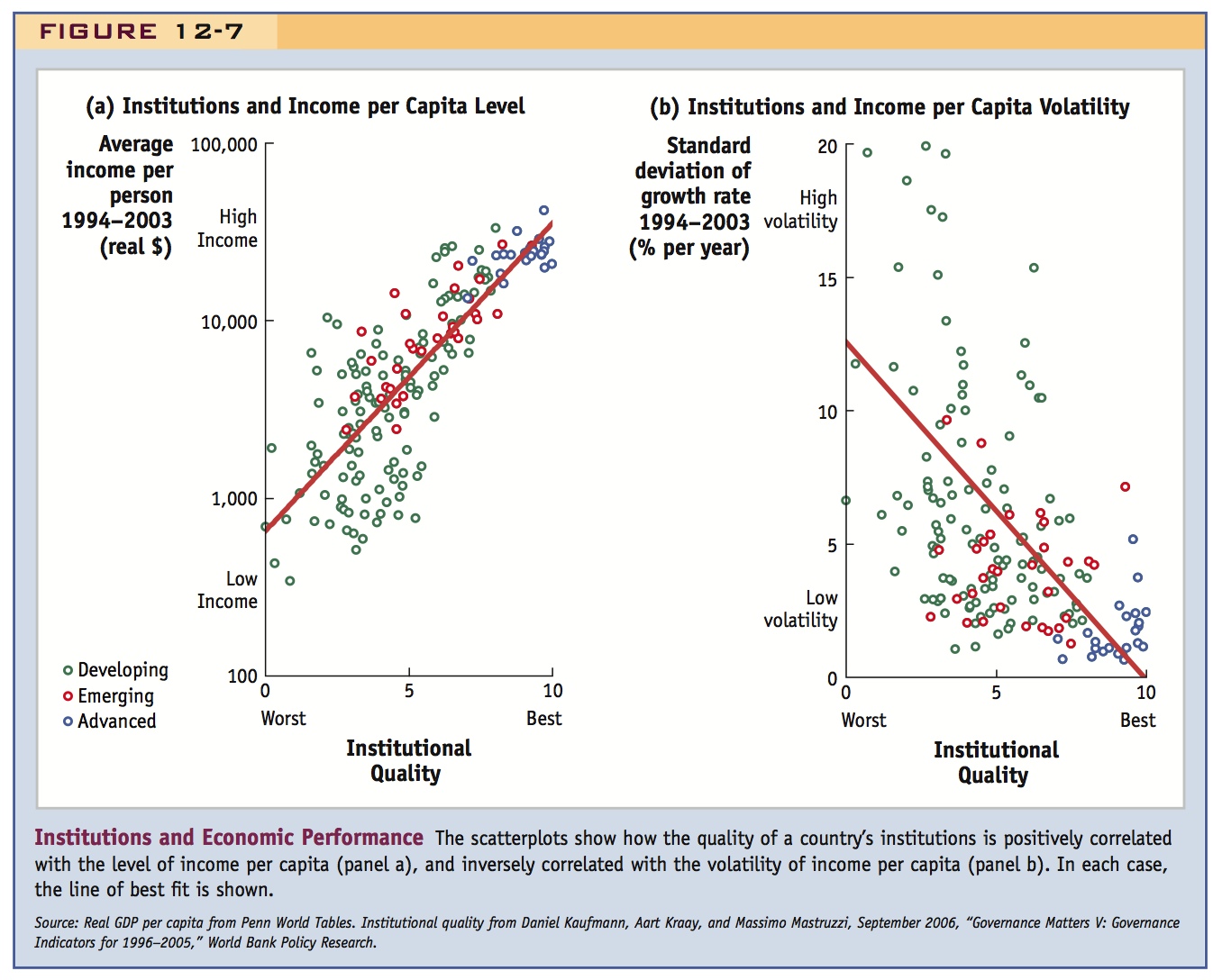

Figure 12-7 shows evidence on the importance of the quality of a nation’s institutions or “governance” using an average or composite of measures on six dimensions: voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. The figure shows that, across countries, institutional quality is strongly correlated with economic outcomes (see Headlines: The Wealth of Nations).

First, we see that better institutions are correlated with more income per capita in panel (a). A government that is unaccountable, unstable, ineffective, unpredictable, corrupt, and not based on laws is unlikely to encourage commerce, business, investment, or innovation. The effects of institutions on economic prosperity are very large. In the advanced countries at the top right of the figure, income per person is more than 50 times larger than in the poorest developing countries at the bottom left, probably the largest gap between rich and poor nations we have ever seen in history. Economists refer to this unequal outcome as “The Great Divergence.”

We also see that better institutions are correlated with less income volatility (i.e., smaller fluctuations in the growth of income per capita, measured by the standard deviation). This result is shown in panel (b) and may also reflect the unpredictability of economic activity in poorly governed economies. There may be periodic shifts in political power, leading to big changes in economic policies. Or there may be internal conflict between groups that sporadically breaks out and leads to conflict over valuable economic resources. Or the state may be too weak to ensure that essential policies to stabilize the economy (such as bank regulation) are carried out.

Recent research has documented these patterns and has sought to show that causality runs from institutions to outcomes and to explore the possible sources of institutional variation. Institutional change is typically very slow, taking decades or even centuries, because vested interests may block efficiency-enhancing reforms. Thus, as the institutional economist Thorstein Veblen famously pointed out, “Institutions are products of the past process, are adapted to past circumstances, and are therefore never in full accord with the requirements of the present.” Consequently, influential recent research seeks to find the roots of institutional (and income) divergence in factors such as:

18

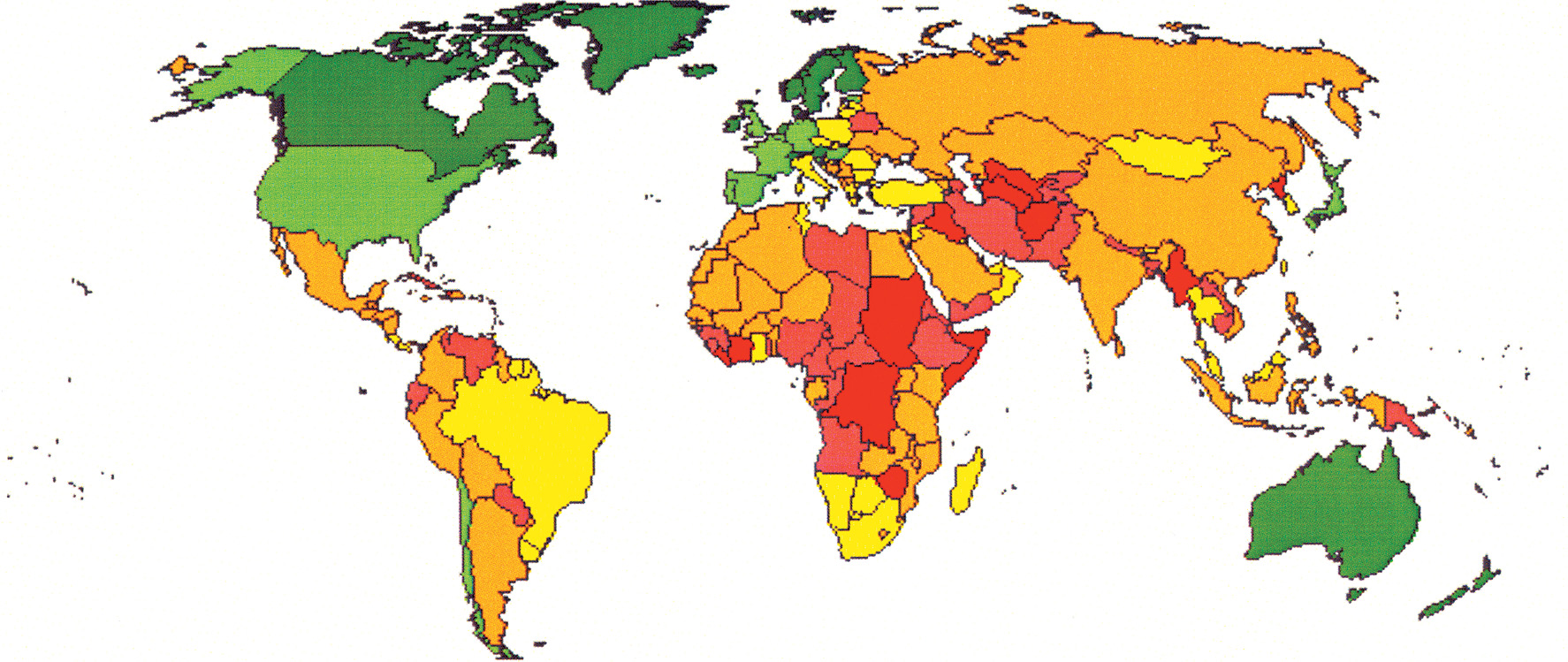

- Actions of colonizing powers (helpful in setting up good institutions in areas settled by Europeans but harmful in tropical areas where Europeans did not transplant their own institutions, but instead supported colonizers and local elites with a strong interest in extracting revenue or resources);

- Types of legal codes that different countries developed (British common law generally resulted in better outcomes than codes based on continental civil law);

- Resource endowments (tropical regions being more suitable for slave-based economies, elite rule, and high inequality; temperate regions being more suited to small-scale farming, decentralized democracy, and better governance).7

19

Key Topics Governance explains large differences in countries’ economic outcomes. Poor governance generally means that a country is poorer, subject to more damaging macroeconomic and political shocks, and cannot conduct policy in a reliable and consistent way. These characteristics force us to think carefully about how to formulate optimal policies and policy regimes in rich and poor countries. One size may not fit all, and policies that work well in a stable well-governed country may be less successful in an unstable developing country with poor governance.

Summary and Plan of Study

4. Summary and Plan of Study

Coming chapters: Chapter 15 develops the link between financial openness and the independence of monetary policy; Chapter 17 elucidates the benefits of financial liberalization; Chapter 19 addresses the choice of exchange rate regime; Chapter 20 explores currency crises; Chapter 21 discusses the economics of the Eurozone.

The functioning of the global macroeconomy is affected in many ways by the actions of governments. Throughout this book, we must pay attention to the possible actions that governments might take and try to understand their possible causes and consequences.

Chapter 15 explores the finding that if a country is financially open, then a fixed exchange rate is incompatible with monetary policy autonomy. Because both goals may be desirable, policy makers are often reluctant to face up to the difficult trade-offs implied by financial globalization. Chapter 17 explores the economic rationales for financial liberalization: If financial openness has clear economic benefits, why are countries slow to liberalize? We explore exchange rate regime choice in detail in Chapter 19 and study the trade-offs involved. Then, in Chapter 20, we study crises, and find that if a country’s policy makers cling to fixed exchange rates, there is a risk of suffering costly crises. The remarkable Euro project, discussed in Chapter 21, throws these issues into sharper perspective in the one region of the world where economic integration has arguably progressed the furthest in recent decades—but where the recent economic crisis has been most severe. The main lessons of our study are that policy makers need to acknowledge trade-offs, formulate sensible goals, and exercise careful judgment when deciding when and how to financially open their economies. Sadly, history shows that, all too often, they don’t.

An article in the FT discusses a World Bank report on how poor governance impedes economic development.

The Wealth of Nations

Social scientists have sought for centuries to understand the essential conditions that enable a nation to achieve prosperity. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith said: “Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.” The following article discusses the poor quality of governance in developing countries and the obstacle this poses to economic development.

It takes 200 days to register a new business in Haiti and just two in Australia. This contrast perfectly encapsulates the gulf between one of the world’s poorest countries and one of the richest. A sophisticated market economy is a uniquely powerful engine of prosperity. Yet, in far too many poor countries, the law’s delays and the insolence of office prevent desperately needed improvements in economic performance.

That makes [the 2005] “World Development Report” among the most important the World Bank has ever produced.* It is about how to make market economies work…. The report is based on two big research projects: surveys of the investment climate…in 53 countries; and the “doing business” project, which identifies obstacles to business in 130 countries…. The argument starts with growth. As the report rightly notes: “With rising populations, economic growth is the only sustainable mechanism for increasing a society’s standard of living.” Happily, “investment climate improvements in China and India have driven the greatest reductions in poverty the world has ever seen.”…Governmental failure is the most important obstacle business faces. Inadequate enforcement of contracts, inappropriate regulations, corruption, rampant crime and unreliable infrastructure can cost 25 per cent of sales. This is more than three times what businesses typically pay in taxes. Similarly, when asked to enumerate the obstacles they face, businesses list policy uncertainty, macroeconomic instability, taxes and corruption at the head of the list. What do these have in common? Incompetence and malfeasance by governments is again the answer….

20

In many developing countries, the requirement is not less government but more and better directed government. What does this involve? Four requirements are listed: a reduction in the “rent-seeking” that affects all countries but mars developing countries to an extreme extent; credibility in the making and execution of policy; the fostering of public trust and legitimacy; and the tailoring of policy responses to what works in local conditions.

One of the conclusions the report rightly draws from this list is that reform is not a one-off event but a process. What is involved is not just discrete and well-known policy changes (such as lower tariffs) but the fine-tuning of policy and the evolution of institutions. This is why, it suggests, the credibility of the government’s journey, as in China, may be more important than the details of policy at each stage along the way.

Turning these broad objectives into specific policy is a tricky business. The Bank describes its core recommendation as “delivering the basics.” These are: stability and security, which includes protection of property…, facilitating contract enforcement, curbing crime and compensating for expropriation; better regulation and taxation, which means focusing intervention where it is needed, broadening the tax base and lowering tax rates, and reducing barriers to trade; better finance and infrastructure, which requires both more competition and better regulation; and transforming labour market regulation, to foster skills, while avoiding the counterproductive interventions that so often destroy employment in the formal sector….

The world’s wealthy countries can also help by lifting their many barriers to imports from developing countries and by targeting aid on improving the investment climate.

Governments then are both the disease and the cure. This is why development is so hard and so slow. The big advance is in the richness of our understanding of what makes an economy thrive. But that understanding also demonstrates the difficulties. The Bank’s recognition of the nature of the disease is at least a first step towards the cure.

Source: Martin Wolf, “Sweep Away the Barriers to Growth,” Financial Times, October 5, 2004. From The Financial Times © The Financial Times Limited 2004. All Rights Reserved.

*A Better Investment Climate for Everyone, World Development Report 2005. Oxford University Press and the World Bank.

21