Principles of Sound Design

As noted, sound design is the hub to which all sonically connected tasks are connected. But it wasn’t until sound designers Ben Burtt and Walter Murch executed breakthrough design work on Star Wars (1977) and Apocalypse Now (1979), respectively, that the art of sound design was permanently elevated to a status equal to image design for moving pictures. Murch, in fact, received the first-ever sound designer movie credit for Apocalypse Now; until then, the term had been used in stage productions but never in a motion picture.

There are core concepts related to the designing of a film’s soundtrack that you need to understand before you move on to learning the basics of recording elements of dialogue, adding effects, or editing or mixing anything. Among these principles, you need to take both a micro and a macro view of the work simultaneously. You must determine what specific elements you want or need—dialogue, effects, Foley, ambient sound, library sound, music, and so on. Then, you must decide on what your parameters can be—how many channels, what special sounds (a spaceship, an alien) you will need to create, while being realistic about what your resources will permit you to include. Will you need a composer and a full-on musical soundtrack? Will you need to license music? What are the acoustics of the places where you will be recording sound? What technology will your budget and personnel permit? Your resources will certainly impact what you can do sonically, but the clever manipulation of sound will permit a smart filmmaker to solve problems while conserving resources (see Producer Smarts: The Sonic Business, below).

When making your decisions, always focus on the end game—that is, what is best for the story. Your decisions about all other matters must emanate from that single goal, and no sound should be gratuitous. Never wed yourself to a sound or a technique merely because it is cool or because you can do it. Ask yourself, should I do it, does it further the story?

HOW SOUND IS USED

HOW SOUND IS USED

Choose a movie you like. Watch it with a pad and pen in hand, making notes about how sound is used narratively, subliminally, and grammatically in the film. Give three key examples of each type of use, explaining the sound and where and when it was used, categorizing it, and defending/explaining your categorization.

Also, remember that sound is an exceptionally collaborative art. Even if you are multitasking and in charge of everything on your student project, you will need to incorporate input from possibly a professor, a director, an editor, other crew members, actors, and even friends, as well as input from test screenings. Revisions will be inevitable, and you should be open minded about this reality and not try to execute your sonic vision in a vacuum.

Modern sound designers generally categorize the roles that sound plays in a movie in three ways, as explained by longtime designer, engineer/inventor, and professor Tomlinson Holman (developer of the high-fidelity THX cinema audio standard, originally on behalf of the Lucasfilm Company, with THX standing for the original name, Tomlinson Holman Experiment). In his book Sound for Film and Television, Holman described these three categories as “narrative,” “subliminal,” and “grammatical.”2

The narrative role of sound revolves around its basic storytelling goal—to help the audience understand where to look or how to feel at any given moment. The subliminal role involves using the medium to have a more subtle emotional impact over time—often, an impact audience members do not consciously comprehend. This happens when sounds are mixed together in such a way that the listener cannot separately identify and analyze each but, when combined, they impact that viewer nonetheless. Finally, sound’s grammatical role involves its use to emphasize specific timing or events in the story—indicating the end of a scene, a dramatic pause, and so on.

Good sound designers understand the different ways they can use the medium to fulfill these roles. These are not technically straightforward concepts to master; rather, they involve the way you as a filmmaker think about sound. With these principles in mind, we now take a look at the first step in your sonic journey: evaluating your script and formulating a sound plan.

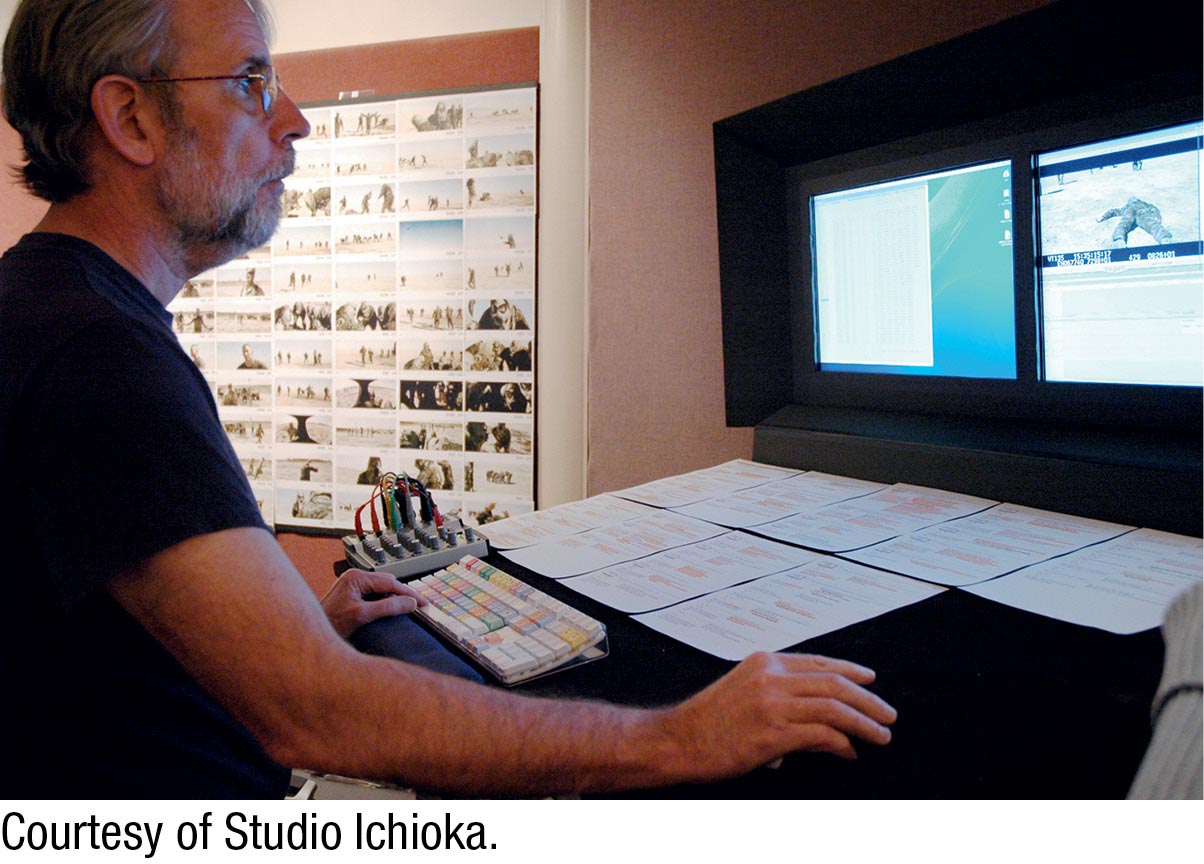

Walter Murch has served as a sound designer, re-recordist, re-recording mixer, and a picture editor during his career and is considered a leading authority on both disciplines and how they need to work together to properly tell stories.

The Sonic Business

Sound is a discipline ripe with opportunities for good producers to expand stories beyond the physical screen’s four corners and simultaneously stretch resources. Planning sound before image capture can often save money and time, or create visual ideas for alternative ways to approach image capture. As students, you will obviously be limited in how many extras, animals, or props you can use, if any, or how many digital artists you can employ. The clever use of sound to illustrate what is “obviously” going on beyond the camera’s lens can reduce your budget and logistical requirements considerably without harming—and, in fact, often helping—your storytelling.

The hysterical use of coconut shells being clapped together—seen on-camera—by the comic geniuses of Monty Python to represent the clop-clop of horse hooves in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) takes the concept to absurd heights. And yet, even there, when plainly satirizing that their production had no budget for horses, the Python guys advanced their story. They showed characters hopping along, making horse noises; and given the nature of their humor, after the initial laughs it hardly seemed out of place. They rightly anticipated that viewers would readily accept that they were supposed to be riding horses; thus, the production directed resources to other things.

So think about how many extras, animals, machines, and props you can afford; which things you can create digitally; and which things you can strategically use sound effects to highlight instead. Does your audience need to see an explosion in your story, or could they simply hear it? While monitoring your overall budget, make sure audio resources have not been given short shrift if you need sound to compensate for other limitations. Make sure you have considered the physical placement of sound crew and equipment on-set, as well as a plan for the separate recording of sound effects or the licensing of library sounds. If you use the “dimension of sound” effectively enough in this way, and if your story happens to be good enough, your audience will be just as enthralled as if you spent seven figures.