Special Effects

Today, special effects are generally considered to be physical real-world techniques—things you can photograph in front of a real camera, as opposed to digital effects. For decades, special effects typically fell into two basic categories: mechanical effects and optical effects. As we shall discuss, some mechanical techniques remain important in terms of creating certain elements for visual effects shots, including pyrotechnics (explosions, fires); animatronics; car crashes; artificial wind, rain, and fog; and the photographing of models or miniatures (see here).

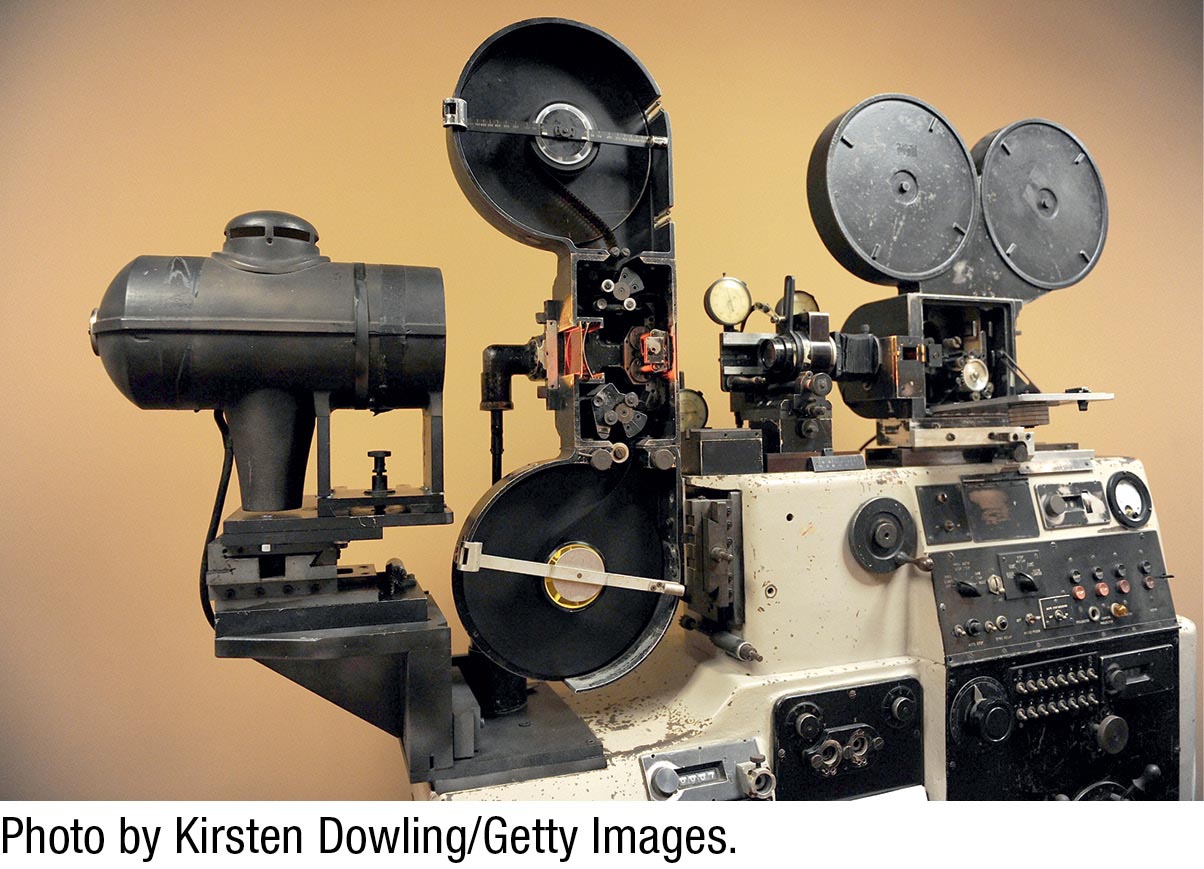

FIGURE 13.1The Linwood Dunn optical printer, named for the pioneering visual effects specialist

The device itself was awarded an Academy Award.

PRECISE

PRECISE

Special effects must be precise—if you blow something up, you may only get one chance to do it (unless you have engineered sets or props that can blast apart and come together again for multiple takes), and so you need to get the shot right the first time. In such cases, consider using multiple cameras and multiple angles and perspectives to capture the effect when the time comes.

Optical effects involved methods of photographing images using camera and laboratory tricks. For years, the industry relied heavily on optical printer technology for much of this work. Optical printers were specialized pieces of hardware that were used to combine positive or negative images into new compositions on an entirely new piece of film. They were essentially movie projectors connected to movie cameras and, for decades, were the most powerful tool Hollywood visual effects artists had at their disposal.

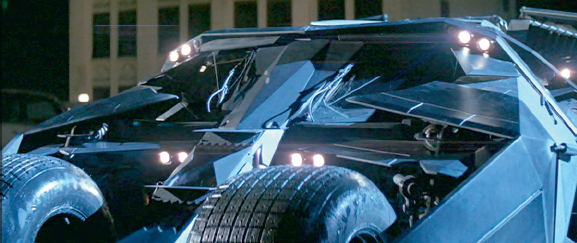

Batman Begins (2005)

Computers have taken over and expanded on these functions, however, and so the optical printer has faded into the past, although the types of illusions it was used for march on in the digital era. Mechanical techniques, by contrast, retain an effective niche to help digital artists craft a greater whole consisting of both real-world and virtual images. The strategic linking of certain practical and digital methods, in fact, lies at the heart of modern visual effects.

Even if your work largely relies on digital tools, understanding practical techniques will be useful, many industry professionals say, because they will give you a frame of reference for relationships and interactions between physical objects based on real-world physics, which you will need to consider as you craft shots. Plus, prominent filmmakers like Christopher Nolan (the modern Batman franchise, Inception, Interstellar) still rely heavily on mechanical techniques. And Ken Ralston insists that his own “understanding of spatial relationships comes from working for years with miniatures and being physically on set, getting tactile experience. Work that information into your brain, and then you will rely on that information later, even when you are working with computers.”5

Therefore, on the high end, practical effects remain a useful piece of the puzzle; and on the low end, they are sometimes more affordable to execute than digital alternatives. Either way, major industry names feel mechanical techniques remain important to understand in a digital filmmaking world. Well-known visual effects supervisor Jerome Chen, for instance, calls them “essential—I can’t do my job without them. It’s always a good idea to get some of the real world into shots to create the best illusion.”6

COLLABORATE

COLLABORATE

Practical effects often require the construction of specially engineered rigs, harnesses, and safety pads, so close collaboration with the prop, stunt, and costume teams is a necessity. Safety of the cast and crew in using practical effects is of paramount importance.

In other words, understanding how practical and digital effects are executed independently, and how they can be combined and used in tandem, will make you a better filmmaker.

Mechanical, or practical, effects take lots of forms; often require a wide variety of equipment and expertise; and, in some cases, cannot be attempted without proper training, licensing, safety procedures, and supervision. Staging a straightforward car crash safely, for instance, is certainly something no first-year film student should attempt. Here is a brief overview of several key techniques:

Animatronics. This term refers to the physical animating of puppets, robots, or other inanimate objects on-set using carefully calibrated and controlled motors and other mechanical methods. Animatronics have been used for decades, but became less popular after the CGI revolution. Today it is often augmented by computer-generated imagery to digitally remove flaws or imperfections in the automated character, but the technique can be quite expensive and, at the professional level, is typically handled by niche companies that specialize in animatronics.

Animatronics. This term refers to the physical animating of puppets, robots, or other inanimate objects on-set using carefully calibrated and controlled motors and other mechanical methods. Animatronics have been used for decades, but became less popular after the CGI revolution. Today it is often augmented by computer-generated imagery to digitally remove flaws or imperfections in the automated character, but the technique can be quite expensive and, at the professional level, is typically handled by niche companies that specialize in animatronics. Front and rear projection. These are in-camera processes of projecting previously filmed or created foreground or background elements in front of or behind an actor or a scene you are photographing on-set to create the optical illusion of those separate layers being combined as you film.

Front and rear projection. These are in-camera processes of projecting previously filmed or created foreground or background elements in front of or behind an actor or a scene you are photographing on-set to create the optical illusion of those separate layers being combined as you film.

USE OPTICAL ILLUSIONS

USE OPTICAL ILLUSIONS

Understand how the human brain processes imagery. Many optical illusions can be used on-set to trick the brain, if you know how they work.

Oblivion (2013)

This scene includes use of a high-tech, modern version of classical projection techniques using powerful digital projectors.

Matte paintings. Originally, matte paintings were done by hand on glass or on background screens that were photographed with live action to create the illusion of actual backgrounds—essentially artistic renderings of a landscape or location. Today, computer matte paintings have taken over to a large degree, but hand-painted mattes are still an effective artistic choice with certain kinds of materials and on low-budget projects for which computer backgrounds are not feasible.

Matte paintings. Originally, matte paintings were done by hand on glass or on background screens that were photographed with live action to create the illusion of actual backgrounds—essentially artistic renderings of a landscape or location. Today, computer matte paintings have taken over to a large degree, but hand-painted mattes are still an effective artistic choice with certain kinds of materials and on low-budget projects for which computer backgrounds are not feasible.

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

A classic example of a traditional matte painting technique.

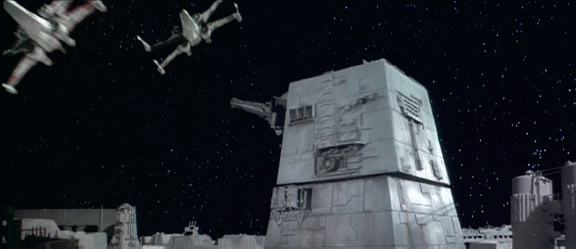

Miniatures and models. This is essentially the building, manipulation, and filming of scale-size models to create illusions that, when combined with other elements and projected from the correct perspective, appear to be life size and real. This was a great art in Hollywood for generations and is still used today, often in combination with computer-generated effects.

Miniatures and models. This is essentially the building, manipulation, and filming of scale-size models to create illusions that, when combined with other elements and projected from the correct perspective, appear to be life size and real. This was a great art in Hollywood for generations and is still used today, often in combination with computer-generated effects.

Star Wars (1977)

The original Star Wars films made extensive use of models and minatures.

SHOOTING MODELS

SHOOTING MODELS

Experiment with filming a model with the goal of making it look full scale and as realistic as possible. Don’t worry about the model’s quality; use the best equipment you have available and film anything from a child’s toy to a handmade model of a building or a car. Here are some hints:

Models frequently look bigger than they are when shot at low angles.

Models frequently look bigger than they are when shot at low angles. Experiment with changing speeds. When movement is slowed down, objects often seem bigger. If you shoot at high speed and play back at a lower speed, you will see this phenomenon. But try it different ways so that you can compare and contrast.

Experiment with changing speeds. When movement is slowed down, objects often seem bigger. If you shoot at high speed and play back at a lower speed, you will see this phenomenon. But try it different ways so that you can compare and contrast. Adding debris, smoke, fog, moody or low light, and other environmental elements can make a model seem more realistic.

Adding debris, smoke, fog, moody or low light, and other environmental elements can make a model seem more realistic. Cut fast between shots if you have a moving element, like a car, and if you are cutting a couple of shots together. Speedy cuts tend to hide flaws and size differences.

Cut fast between shots if you have a moving element, like a car, and if you are cutting a couple of shots together. Speedy cuts tend to hide flaws and size differences.

Hanging miniatures. This is a popular way to use models to create special-effect shots in-camera. In this case, miniatures are used instead of a matte painting in the foreground of a shot, with action taking place behind the miniature. This is a forced perspective optical-illusion technique—a way of showing the audience a point of view that appears to make an element seem closer, farther away, larger, or smaller than it really is, when photographed from certain angles.

Hanging miniatures. This is a popular way to use models to create special-effect shots in-camera. In this case, miniatures are used instead of a matte painting in the foreground of a shot, with action taking place behind the miniature. This is a forced perspective optical-illusion technique—a way of showing the audience a point of view that appears to make an element seem closer, farther away, larger, or smaller than it really is, when photographed from certain angles. Motion-control photography. Once common for special-effects work, this method remains in use today, although only for specialized applications due to cost and logistical limitations. The basic idea is to establish mechanical or computerized hardware command of a camera in order to precisely control its movement to repeat or copy previous camera movements. In the analog era, motion control was done with expensive and laborious mechanical systems; later, computer control systems took over. Today, the expense and time it takes has largely forced the industry to move toward digital camera tracking techniques, discussed later in this chapter.

Motion-control photography. Once common for special-effects work, this method remains in use today, although only for specialized applications due to cost and logistical limitations. The basic idea is to establish mechanical or computerized hardware command of a camera in order to precisely control its movement to repeat or copy previous camera movements. In the analog era, motion control was done with expensive and laborious mechanical systems; later, computer control systems took over. Today, the expense and time it takes has largely forced the industry to move toward digital camera tracking techniques, discussed later in this chapter. Pyrotechnics. This is basically the art and science of using explosive or flammable materials in a controlled manner to safely create and film manageable fire and explosion elements. This technique is usually strictly regulated, and typically requires special licenses, permits, and, sometimes, safety equipment and personnel, depending on the nature of the stunt and the jurisdiction where it is being conducted. On a student project, you should never attempt a pyro effect without first obtaining permission from your professor and school, and all appropriate authorities, as it can be extremely hazardous if you don’t know what you are doing.

Pyrotechnics. This is basically the art and science of using explosive or flammable materials in a controlled manner to safely create and film manageable fire and explosion elements. This technique is usually strictly regulated, and typically requires special licenses, permits, and, sometimes, safety equipment and personnel, depending on the nature of the stunt and the jurisdiction where it is being conducted. On a student project, you should never attempt a pyro effect without first obtaining permission from your professor and school, and all appropriate authorities, as it can be extremely hazardous if you don’t know what you are doing. Stop motion and go motion. These are forms of a time-honored animation technique that effects pioneers Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen made famous in the pre-digital era. They involve the photographing of models, puppets, props, and other elements one frame at a time, moving them minutely for each frame so that when they are edited together, they give the illusion of motion. Go motion is a variation on stop motion in which motion blur is strategically mixed into each frame by slightly moving the animated object during exposure of each frame in-camera, resulting in a naturalistic motion blur.

Stop motion and go motion. These are forms of a time-honored animation technique that effects pioneers Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen made famous in the pre-digital era. They involve the photographing of models, puppets, props, and other elements one frame at a time, moving them minutely for each frame so that when they are edited together, they give the illusion of motion. Go motion is a variation on stop motion in which motion blur is strategically mixed into each frame by slightly moving the animated object during exposure of each frame in-camera, resulting in a naturalistic motion blur. Squibs. These essentially function as tiny explosive devices configured with electrical triggering mechanisms. They can be used to generate small explosions or bullet holes on-set or be filled with liquids to simulate blood spurts.

Squibs. These essentially function as tiny explosive devices configured with electrical triggering mechanisms. They can be used to generate small explosions or bullet holes on-set or be filled with liquids to simulate blood spurts. Weather effects. These involve the use of sprinklers, hoses, water tanks, air hoses, fans, and special fog and smoke machines to emulate real-world weather conditions.

Weather effects. These involve the use of sprinklers, hoses, water tanks, air hoses, fans, and special fog and smoke machines to emulate real-world weather conditions.