Defining the Audience

AUDIENCE FIRST!

AUDIENCE FIRST!

Have your audience in mind at every step of your process—from idea, to screenplay, through production, and when you are finishing up. Guide your decision making by asking, What does the audience need or want at this point in the movie?

Marketing is the process of offering your work to your audience with two goals in mind: to create awareness of your movie and to drive their desire to buy admission when it opens (this is called want-to-see). This means the first step in constructing any marketing plan is answering the following question: Who is your audience? In other words, who did you make your movie for?

In a classroom environment, perhaps you made it for your teacher or your peers; either way, you knew who you were making it for before you began. Outside of class, you will likely hope to reach a larger (and paying) audience, and the same should also be true—you should know who your audience will be from the moment you begin the script and while you are making the film.

Unfortunately, not all filmmakers define their audience beforehand. They believe that if they are interested in a story, other people will be, too, but that does not always prove to be true. Then they find themselves trapped because they have a movie that no one wants to see. Although it is essential to tell a terrific story, if that story is one that people aren’t interested in watching, no one will be able to experience your talent. Make a movie for a specific audience, large or small; don’t make a movie and then try to figure out who the audience is.

With the audience identified early in the process, it becomes important to learn more about them and connect with them as the film gets closer to release. Doing so will allow you to define them even more specifically, which will help you target your marketing more effectively. To help you do this, you first need to screen your movie.

Learning from Your Audience While You Work Your Movie

Before you send your movie out to be seen by the general public, you’ll want to make sure it works the way you want it to work. Playability is how well the audience responds while watching the film—

You can accomplish a test screening in several ways. You can gather friends in a room and show the film, or even screen it privately in an auditorium. This early feedback will be helpful but not determinative: they are your friends, after all. To get better information, you’ll want to do a screening for people who don’t know you and therefore have no stake in preserving your feelings. This is called a recruited screening, which is a type of screening that movie studios conduct regularly (see Action Steps: Preview Screening, below).

At a recruited screening, audience members are invited (recruited) to come to a special screening of a new film; more often than not, they are given only a generic, two-

The goal of the screening is to figure out what you can learn from your intended audience. Depending on their feedback, you may need to go back to the editing room and improve the film, in which case you’ll want to test again. Studios frequently do iterative edits and preview screenings five or more times. You should do as many as you want (or as many as you have time for) to make your project as good as it can be.

Screenings also allow you to learn more about who your audience is. You may find that your movie appeals more to one kind of person than another—

ACTION STEPS

Preview Screening

Recruit audience members who don’t have previous connections to the film (this includes friends of friends). You need at least 20 people to discern a general sentiment. Studios routinely do preview screenings for 200–

Recruit audience members who don’t have previous connections to the film (this includes friends of friends). You need at least 20 people to discern a general sentiment. Studios routinely do preview screenings for 200–400 people; though they get everyone’s feedback, they will often hold a small percentage of the audience back for more in- depth questions.  Recruit about 20 percent more people than you need; it is inevitable that not everyone will show up. At the time of the screening, if less than 80 percent of your invited audience show up, that tells you something: the movie doesn’t seem compelling enough to them. Think about how you described the movie, and resolve to consider this issue based on the test audience’s reaction. A less-

Recruit about 20 percent more people than you need; it is inevitable that not everyone will show up. At the time of the screening, if less than 80 percent of your invited audience show up, that tells you something: the movie doesn’t seem compelling enough to them. Think about how you described the movie, and resolve to consider this issue based on the test audience’s reaction. A less-than- full theater can also cause those in attendance to be predisposed not to like the film.  Welcome the audience. Keep in mind that the greeter should be someone who has nothing to do with the film, so that the audience does not feel as if they have to be polite in their reactions. A typical welcome speech is, “Welcome to this special screening. The film you’re about to see isn’t finished yet—

Welcome the audience. Keep in mind that the greeter should be someone who has nothing to do with the film, so that the audience does not feel as if they have to be polite in their reactions. A typical welcome speech is, “Welcome to this special screening. The film you’re about to see isn’t finished yet—you may notice some imperfections in color and sound, and some of these things are temporary. Don’t worry, when the film is finished, all those problems will be corrected. Enjoy the show!”  Screen the film. Watch closely for the audience’s reactions, both verbal and nonverbal. Do they lean forward to watch, or do they seem distracted? Do they take out their phones and start texting, get up and go to the bathroom (or leave altogether), or stay involved? Where is their interest keen? Where does it wane? The experience of watching your movie with an audience for the first time is a powerful source of information. To study and preserve the recruited-

Screen the film. Watch closely for the audience’s reactions, both verbal and nonverbal. Do they lean forward to watch, or do they seem distracted? Do they take out their phones and start texting, get up and go to the bathroom (or leave altogether), or stay involved? Where is their interest keen? Where does it wane? The experience of watching your movie with an audience for the first time is a powerful source of information. To study and preserve the recruited-screening experience, many studios use infrared cameras to film the audience’s reaction. They then edit a special version of the film together— the film playing in one screen window, and the audience’s reaction playing in synchronization in another window.  Get audience reaction. There are three ways to do this:

Get audience reaction. There are three ways to do this:

- Watch and listen to what they are saying to one another. This approach is the easiest to do but provides the least information.

- Have a group discussion or a focus group, led by someone not connected to the film. (You can sit in the back and listen.) The discussion leader should ask if there were any parts that didn’t seem clear, what the audience liked and didn’t like, and what they would tell their friends about the film.

- Do a survey. Studios often combine a written survey (for the whole audience) with a focus group of about 20 people. The two most important pieces of information to get from an audience can be gotten through the following questions: How did you feel about the movie? and Are you likely to recommend this movie to your friends? These are generally put on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being The movie was excellent and I will definitely recommend this movie to my friends. The “definitely recommend” is the best gauge of how people really feel about your movie.

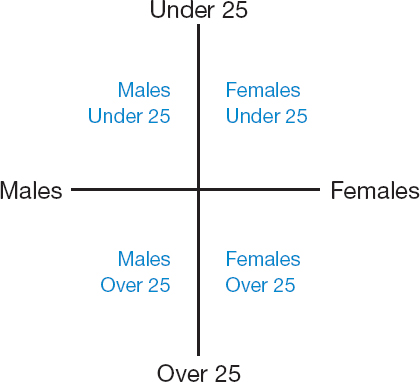

FIGURE 14.1The four quadrants as designated by movie marketing

Kinds of Audiences

At this point, you are probably realizing that your movie is analogous to a product—a consumer good, like laundry detergent or toothpaste—and that it will need to be “sold” like one. The process for selling begins with a deep understanding of whom you are selling to.

WHAT’S YOUR NICHE?

WHAT’S YOUR NICHE?

Follow the marketing mantra, “Go big, go niche, or go home.” And, because only big Hollywood movies have the advertising budget to “go big,” you should generally make sure to “go niche.”

Marketing is a sociocultural activity, and marketing professionals often use the sociocultural constructs of gender and race to describe audiences. The traditional understanding of movie sales breaks the audience into four sections, or quadrants: men under 25, men over 25, women under 25, and women over 25.

Hollywood movies usually find their predominant audience in one of the four quadrants. Although the following four examples may appear as age- and gender-biased generalizations, they reflect the way marketers would describe audience composition of some movie genres in the past decade:

Action movies with younger lead characters (such as the Fast and Furious franchise) appeal primarily to men under 25.

Action movies with younger lead characters (such as the Fast and Furious franchise) appeal primarily to men under 25. Action movies with older lead characters (such as The Expendables franchise) appeal primarily to men over 25.

Action movies with older lead characters (such as The Expendables franchise) appeal primarily to men over 25. Romantic comedies (such as the 2014 remake of About Last Night) appeal primarily to women under 25.

Romantic comedies (such as the 2014 remake of About Last Night) appeal primarily to women under 25. Period dramas (such as the 2010 Oscar winner The King’s Speech) appeal primarily to women over 25.

Period dramas (such as the 2010 Oscar winner The King’s Speech) appeal primarily to women over 25.

Of course, there are many genres beyond these, and audience interest in any film will be from a mix of quadrants. Some movies—those that are highly financially successful—have significant audience interest from more than one quadrant. A movie everyone goes to is called a “four-quadrant movie.” The Hunger Games (2012) and its sequels are examples of four-quadrant movies. Often, major studio projects may not be able to justify their budgets or even get greenlit unless studio executives decide they have potential to be true four-quadrant films.

DETERMINING YOUR AUDIENCE

DETERMINING YOUR AUDIENCE

Using your class project as an example, identify the audience that might go to see it if it were playing in a local theater. Support your audience choice with evidence by citing commercial movies that are similar to your class film, correlating the audience that attended those movies with your project.

However, for student and independent films, those four quadrants offer little in terms of specificity or information you can really use. In fact, many independent films are often made at a low budget because they target a very select group. Enter the power of niches. A niche is a narrowly defined slice of the audience. In the world of niches, there are no longer four quadrants; there might be 44, or even 444, different audience segments, each of which can be targeted, or communicated to, with the utmost specificity. For example, one niche might be African American families who go to movies with their elementary-school-age children. Another might be college students with an interest in independent music scenes. As you can see, niches cut through and beyond the traditional four quadrants to define audiences with more nuance and specificity.

Once you learn your movie’s niche (or niches, because some films appeal to more than one niche), you can use the information to your advantage. Rather than trying to reach out to millions of people, you may only be trying to reach a few hundred or a few thousand. The niche can become your movie’s core audience and core fans. They won’t be the only audience, but they will be the people who show up on opening night because the project speaks directly to them and their demographic or psychographic needs, and they will be the ones who tell their friends and spread the word. By targeting your audience effectively, you maximize the potency of your film’s marketing message (see here). And every once in a while, a niche film becomes a phenomenon and attracts audiences that were never expected, such as occurred with the ultra low–budget movie, The Blair Witch Project (1999). But be cautious about “the phenomenon phenomenon,” because it is far more difficult to strategically create one than to see one organically grow when you least expect it. Concentrate, instead, on your niche strategy, and if things evolve exponentially beyond those specific targets, all the better—chances are your expert handling of your niche strategy had something to do with getting the whole thing going, whether you planned it that way or not.