Budgeting

As noted, you first need to create a preliminary schedule in order to construct a realistic budget for your production. A movie budget is essentially the financial representation of what you expect it will cost to execute that schedule and deliver the elements you are planning to create to make your movie. This is why we have emphasized that the two go together—

As student filmmakers, your primary goal in making your movie is not (yet) the same as the primary goal of Hollywood studios: the almighty profit motive. However, at a foundational level, you still need to be able to figure out if you can afford to make the movie you have designed. But we have also emphasized what is obvious—

It is crucial to remember: Your budget is not the creative limiting factor. It is the creative defining factor. Whether the budget is $100 or $100 million, it is still a finite number (exceeded by at least 10 percent in many cases). You and your team will have to figure out how to squeeze every penny out of whatever that finite number is to tell your story.

Whatever choices you make, there will be some kind of cost associated with them, even if those costs are bottom-

Budget Document

Film budget documents generally have a standard format, and the important thing to remember is that the more detail included in your budget, the more accurate it will be and the better off the project will be. With basic skills, you can create a budget document using an Excel spreadsheet, but a wide range of budget template software tools are available at low or no cost across the Internet, including many tailored specifically for movie production. Whatever tool you use, the general format will look like this:

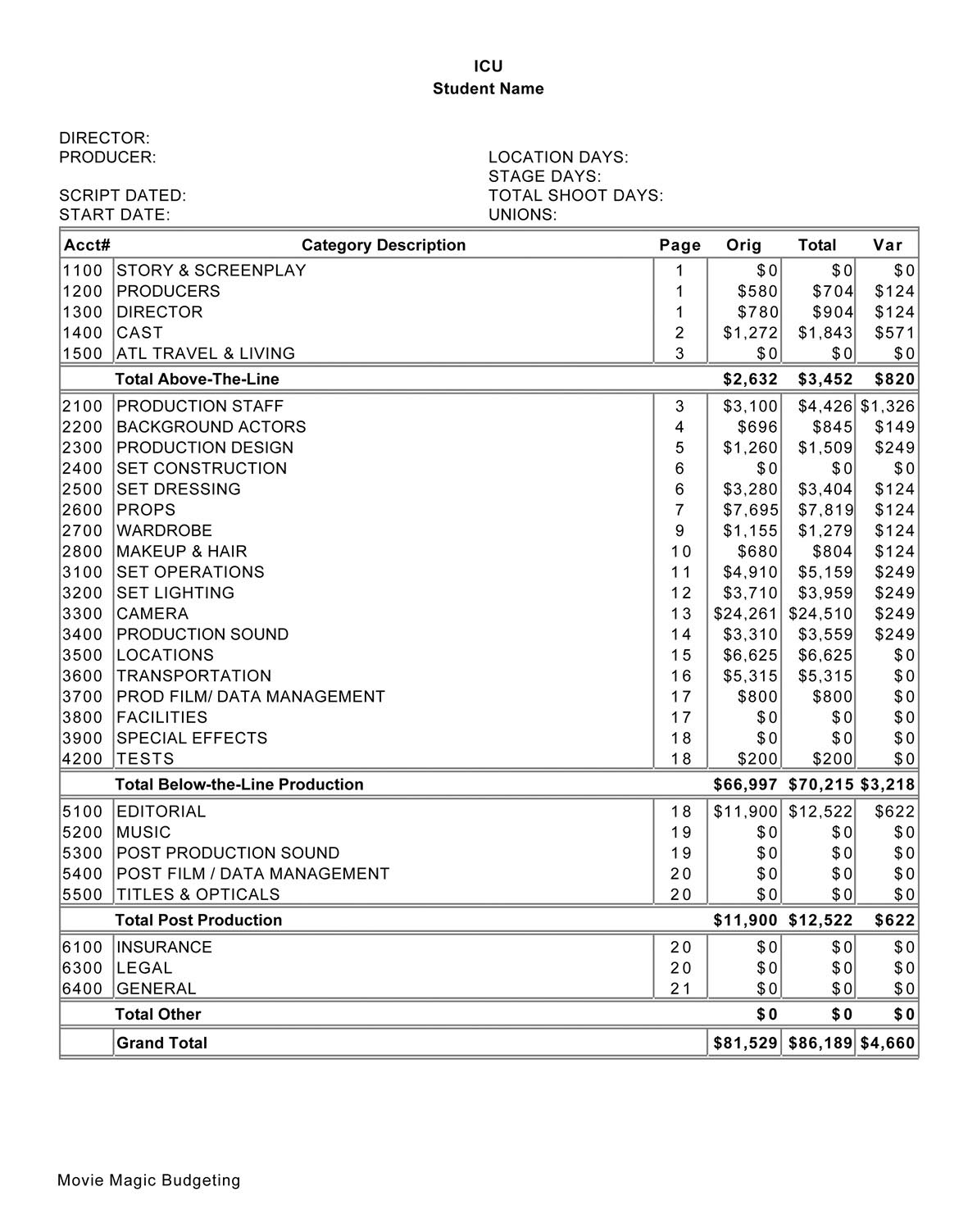

FIGURE 5.2

Sample budget top sheet

Top sheet. This is essentially a cover sheet that summarizes the budget document’s major categories and lists the bottom line, or total cost of production. The top sheet is the first thing that financiers, studio heads, or—in your case—possibly your professor will review to get a sense of where your money is being allocated (see Figure 5.2). A complicated professional top sheet would likely list everything by department (camera, grip, transportation, office, second unit). As a student filmmaker, depending on the complexity of your project, you might also break things down that way. At a minimum, make your top sheet a fairly simple summary page that lists your hard costs (things you absolutely must find a way to pay for, such as gas, food, camera rental, and location fees), no-cost items, and all funding sources and amounts, thus providing a simple mathematical illustration of how much you need to spend juxtaposed with how much you are taking in. If there is money left over or an even zero at the bottom, you are in relatively good shape; if there is a negative amount resulting as your bottom line, you had better start revising your plans immediately.

Top sheet. This is essentially a cover sheet that summarizes the budget document’s major categories and lists the bottom line, or total cost of production. The top sheet is the first thing that financiers, studio heads, or—in your case—possibly your professor will review to get a sense of where your money is being allocated (see Figure 5.2). A complicated professional top sheet would likely list everything by department (camera, grip, transportation, office, second unit). As a student filmmaker, depending on the complexity of your project, you might also break things down that way. At a minimum, make your top sheet a fairly simple summary page that lists your hard costs (things you absolutely must find a way to pay for, such as gas, food, camera rental, and location fees), no-cost items, and all funding sources and amounts, thus providing a simple mathematical illustration of how much you need to spend juxtaposed with how much you are taking in. If there is money left over or an even zero at the bottom, you are in relatively good shape; if there is a negative amount resulting as your bottom line, you had better start revising your plans immediately. Above-the-line costs. Detailed breakdown pages will follow that will further delineate costs based on category, with above-the-line costs coming first.

Above-the-line (ATL) costs refer to the generally more expensive costs of studio films—usually talent costs in the form of producers, actors, directors, writers, rights acquisition, and sometimes very highly paid craftspeople. On a student film, ATL costs may be minimal, since you are not typically paying much, if anything, to actors and are likely producing and directing yourself.

Above-the-line costs. Detailed breakdown pages will follow that will further delineate costs based on category, with above-the-line costs coming first.

Above-the-line (ATL) costs refer to the generally more expensive costs of studio films—usually talent costs in the form of producers, actors, directors, writers, rights acquisition, and sometimes very highly paid craftspeople. On a student film, ATL costs may be minimal, since you are not typically paying much, if anything, to actors and are likely producing and directing yourself. Below-the-line costs. As you might expect,

below-the-line (BTL) costs refer to the day-to-day costs of crew and equipment required for the physical production of the movie. These would include cameras, set construction, and tape or digital media. On a student film, if you have any extensive costs at all, they will likely come out of the BTL category.

Below-the-line costs. As you might expect,

below-the-line (BTL) costs refer to the day-to-day costs of crew and equipment required for the physical production of the movie. These would include cameras, set construction, and tape or digital media. On a student film, if you have any extensive costs at all, they will likely come out of the BTL category.

In all budget documents, it is best to itemize your ATL and BTL costs. On the professional level, this can run on for thousands of lines and dozens—sometimes hundreds—of pages. Each line will account for one crew member, item to be rented or purchased, or supply to be consumed; the daily or weekly rate for the item; how many hours, days, or weeks it will be used; what scenes it will be used for, and the costs per scene or location in many cases; and the subtotal for that item. Each line of detail also ties to the schedule. Taxes (such as sales taxes) and fringes (such as Social Security payments, state disability insurance, union-mandated health and pension benefits) and other fees will have their own lines and sections; there will be categories for what currencies are being used or transferred, as well as a host of minute details that would be of interest only to studio or bank accountants. Also, in the modern era of digital filmmaking, visual effects can be so large and complex and eat up so many resources that they frequently go through their own, entirely separate scheduling and budgeting process.

Obviously, not all of this will apply to you right now. Still, this approach is the only real way that you, and anyone you are responsible to—your professor or school, financiers, family, partners, or friends—can know how your resources are being used; more importantly, since you are students, it is the only way you can possibly learn proper principles and procedures for motion picture budgeting. Though this may never become your passion as a filmmaker, if you ever hope to participate in producing your own work at any future level, having this knowledge will serve you well.

REMEMBER POSTPRODUCTION

REMEMBER POSTPRODUCTION

When crafting a budget, don’t shortchange postproduction, particularly sound effects. On low-budget projects in particular, it is likely that production sound will be far less than pristine and will need sweetening or looping and, more likely than not, sound effects added to make your illusions come to life. Prioritize limited resources based on the most essential things, and work backward from there. At the most rudimentary level, getting enough coverage and corresponding elements to tell your story well is what is absolutely essential, but you will need resources for postproduction as well.

Be Resourceful

One of the positive things about making low-budget movies is that reality can lead to better creative choices, and not only where the on-screen narrative is concerned. As students, you have the opportunity—indeed, the requirement—to be ultra-resourceful on the business side of your project as well, and by definition, that resourcefulness requires a level of creativity and even panache. The better you get at figuring out ways to insert zeros into the “costs” column on your budget document, the more success you will eventually find at being an innovative and free-thinking, out-of-the-box filmmaker.

And when we say “resourceful,” we mean in terms of finding ways to get jobs done and equipment and materials procured without spending money. There is an art to developing the skill of finding low- or no-cost labor, equipment, props, locations, costumes, and so on, and you will only get better at it over time. However, there are some tried-and-true shortcuts and tips that independent filmmakers have used for generations that you can consider, depending on your project’s needs (see also Action Steps: Planning Crew Meals on a Tight Budget, below). Among these are the following:

Write or revise your script specifically to adhere to your budget and locations.

Write or revise your script specifically to adhere to your budget and locations. Thoroughly research what your film school and other organizations offer students in terms of gear and resources, and inquire as to whether you can partner with the school or others on ownership of your film’s copyright, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Your school or other “investors” may chip in equipment, funds, or other resources in return for an ownership stake in the movie (see Producer Smarts: Finding Funding, below).

Thoroughly research what your film school and other organizations offer students in terms of gear and resources, and inquire as to whether you can partner with the school or others on ownership of your film’s copyright, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Your school or other “investors” may chip in equipment, funds, or other resources in return for an ownership stake in the movie (see Producer Smarts: Finding Funding, below). To the degree you need to bring in crew in different disciplines, such as cinematography or editing, if you do not already have access to equipment, try to lure people who own their own equipment. This is particularly helpful with your cinematographer, editor, and location mixer.

To the degree you need to bring in crew in different disciplines, such as cinematography or editing, if you do not already have access to equipment, try to lure people who own their own equipment. This is particularly helpful with your cinematographer, editor, and location mixer. Inquire about discounts and free rentals of equipment for student filmmakers from equipment rental houses and local businesses. Some rental houses will also lower costs based on shorter-term rentals.

Inquire about discounts and free rentals of equipment for student filmmakers from equipment rental houses and local businesses. Some rental houses will also lower costs based on shorter-term rentals. Take advantage of free or low-cost cinematography, lighting, scheduling, and budgeting apps that are readily available to consumers, as well as specialized apps for other disciplines that are often low cost and tailored to the filmmaking community.

Take advantage of free or low-cost cinematography, lighting, scheduling, and budgeting apps that are readily available to consumers, as well as specialized apps for other disciplines that are often low cost and tailored to the filmmaking community. Follow our advice in Chapter 4 and use furniture and set pieces from your own home and the homes of friends and family members.

Follow our advice in Chapter 4 and use furniture and set pieces from your own home and the homes of friends and family members. Use homes, property, and business locations of friends and family as shooting locations if available. Figure out if an area in your own home, your garage, or a warehouse or storage space that you have access to could be converted into a stage, if needed.

Use homes, property, and business locations of friends and family as shooting locations if available. Figure out if an area in your own home, your garage, or a warehouse or storage space that you have access to could be converted into a stage, if needed. Have cast, crew, classmates, friends, and family provide hair and makeup services—you already likely know people with good skills in these and similar areas.

Have cast, crew, classmates, friends, and family provide hair and makeup services—you already likely know people with good skills in these and similar areas. Trade credits and appearances of people, logos, businesses, and places for the right to shoot in locations or for labor, food, and equipment from locals in the town where you are shooting.

Trade credits and appearances of people, logos, businesses, and places for the right to shoot in locations or for labor, food, and equipment from locals in the town where you are shooting. Search for unsigned or unproduced local musicians in your school or community who are looking for exposure, and put their music in your film—and even get their help scoring the film—in return for exposing them to a wider audience and letting them promote your use of their work for their own needs.

Search for unsigned or unproduced local musicians in your school or community who are looking for exposure, and put their music in your film—and even get their help scoring the film—in return for exposing them to a wider audience and letting them promote your use of their work for their own needs.

Remember: all such items, even if coming to the project at no cost to you, need to be listed on your budget document and tracked. You may owe someone a credit in return for the resource or future revenue if the movie earns any money down the road, or you may need the information for tax purposes later on.

TRACK YOUR SPENDING

TRACK YOUR SPENDING

Run a weekly report to indicate whether your budget and spending is on track. On professional projects, a production accountant is assigned to monitor expenditures during production and feed the production management team up-to-date information on money being spent in the form of frequent cost reports that are generated every day, sometimes even multiple times during a day.

Finding Funding

We have discussed how to be resourceful in terms of finding people, equipment, and services you won’t have to pay much—if anything—to procure. However, a far more complex art involves the world of real film financing. There are certain pathways that exist for student filmmakers to find ethical methods to raise funds for projects under particular conditions. Obviously, the most feasible way for students to obtain funding is to enter a student competition or earn a scholarship or grant through their school or any of a number of national and international student film competitions.

Additionally, there is nothing to stop an enterprising student from holding fund-raising activities in the real world, or online through crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter. Thousands of student and independent film and video projects have raised funds and been produced this way. Also, you might offer a credit or equity stake in your movie to anyone who might want to give or lend you money to make your movie, but you should seek out competent legal and financial advice beyond the scope of this book before you go down the road of borrowing money. But what is a student filmmaker to do when winning a competition or raising large sums aren’t feasible options?

While motion picture financing can be an arcane and confusing world, at a minimum you should strive to understand the basic concepts of how things work. Some of these often-used financing methods may not be viable for you yet. At your level, we are not urging you to seek out investors or borrow money, but rather to start learning how the financing game works for future reference if you are interested in continuing your filmmaking education. (Please remember that you must always have professional legal and financial advice before seeking financing on any film.) Well-established methods for financing major projects typically include the following:

Seed investors. These people simply believe in a project and expect to get a return somehow. Typically, these investors provide “seed money,” a small amount of up-front money to develop a project or to begin filming. Filmmakers might use that seed money to make a short trailer out of the early footage, often called a sizzle piece, for the express purpose of selling other investors on the project’s potential. Though often risky for the investor, it is the most typical way students get outside funding help beyond the possibilities of grants or scholarships.

Seed investors. These people simply believe in a project and expect to get a return somehow. Typically, these investors provide “seed money,” a small amount of up-front money to develop a project or to begin filming. Filmmakers might use that seed money to make a short trailer out of the early footage, often called a sizzle piece, for the express purpose of selling other investors on the project’s potential. Though often risky for the investor, it is the most typical way students get outside funding help beyond the possibilities of grants or scholarships. Nonprofit foundation and government grants. Under certain conditions, these grants are sometimes applicable to student filmmakers.

Nonprofit foundation and government grants. Under certain conditions, these grants are sometimes applicable to student filmmakers. Tax incentives and rebates. If projects bring business to other states or countries, they can sometimes be given tax breaks or cash rebates in return for shooting there.

Tax incentives and rebates. If projects bring business to other states or countries, they can sometimes be given tax breaks or cash rebates in return for shooting there. Presales. This involves a method of providing financing in return for the right to distribute the film in different countries before it is even made (preselling the rights).

Presales. This involves a method of providing financing in return for the right to distribute the film in different countries before it is even made (preselling the rights). Debt financing. This means getting a bank loan, to provide immediate cash the production can use. The loan will be paid back when tax incentives, rebates, or presales contracts are paid in full—plus interest to the bank, of course.

Debt financing. This means getting a bank loan, to provide immediate cash the production can use. The loan will be paid back when tax incentives, rebates, or presales contracts are paid in full—plus interest to the bank, of course. Co-productions. These are collaborative productions, where two or more companies jointly produce the movie, with each company putting in financial and other resources.

Co-productions. These are collaborative productions, where two or more companies jointly produce the movie, with each company putting in financial and other resources. Private equity financing. This allows private individuals or organizations to invest cash in return for partial or full ownership of the film.

Private equity financing. This allows private individuals or organizations to invest cash in return for partial or full ownership of the film.

IDENTIFY HARD COSTS

IDENTIFY HARD COSTS

Create a sample film budget for a short student film based on a simple three-day movie shoot using software you may already own or can easily acquire. The budget can be from a real project you are currently developing or an example of one using numbers for resources you think you could realistically access. The point of the exercise is to identify what absolute hard costs you think you would have to incur to make a short student film like the one you are envisioning. What expenses are there simply no way to avoid—food? gas? camera rentals? travel? location fees or permits?—and how much will those expenses cost you? Research such costs in detail.

ACTION STEPS

Planning Crew Meals on a Tight Budget

Professional filmmakers say if there is one basic, logistical matter a young filmmaker should not overlook in scheduling and budgeting a movie shoot, it is the issue of food and meals for cast and crew. Although this may seem insignificant, in point of fact, even on a small production, food can turn into a major line item on a budget. And just as important, failure to schedule time for meals and provide a way to conveniently access food can directly impact efficiency—simply put, the old adage that an army (even a small one) moves on its stomach is true, particularly in filmmaking. This is especially true in the world of student filmmaking, in which most of the people helping you are volunteers. Feeding these people and thus keeping them content may well be the only tangible benefit you can provide them during production.

Therefore, here are some simple and basic tips about getting the crew fed in an affordable way, and scheduling meals in such a way as to improve efficiency on-set:

Depending on conditions, try to schedule your shoot to begin after breakfast or end before dinner.

Depending on conditions, try to schedule your shoot to begin after breakfast or end before dinner.

Strategically schedule only those actors and crew members you know you will need during mealtimes. Even though your lead actors may be needed all day, your roomful of extras can be released before you need to feed them.

Strategically schedule only those actors and crew members you know you will need during mealtimes. Even though your lead actors may be needed all day, your roomful of extras can be released before you need to feed them. Check with local restaurants and markets in the town and near the locations where you are filming—some will provide deals or discounts for student productions if you approach them and make special requests, or negotiate to put their restaurant, market, sign, or logo in your movie.

Check with local restaurants and markets in the town and near the locations where you are filming—some will provide deals or discounts for student productions if you approach them and make special requests, or negotiate to put their restaurant, market, sign, or logo in your movie. Keep snacks on-set. Whereas the big studios have whole departments devoted to on-set food catering—craft services—affordable snacks, such as veggies, chips, and crackers, can be made readily available to large groups at very little expense when you buy in bulk at wholesalers such as Costco.

Keep snacks on-set. Whereas the big studios have whole departments devoted to on-set food catering—craft services—affordable snacks, such as veggies, chips, and crackers, can be made readily available to large groups at very little expense when you buy in bulk at wholesalers such as Costco. Cook for your crew. If you or a spouse, significant other, classmate, sibling, parent, friend, or colleague have great cooking skills and the time, it can frequently be far cheaper to whip up large batches of tasty dishes and cart them over to the set than to pay for restaurant or catered food.

Cook for your crew. If you or a spouse, significant other, classmate, sibling, parent, friend, or colleague have great cooking skills and the time, it can frequently be far cheaper to whip up large batches of tasty dishes and cart them over to the set than to pay for restaurant or catered food.

UPM’s Emergency Kit

Budgeting and scheduling software tools

Budgeting and scheduling software tools Near-set office space for posting schedules and daily reports

Near-set office space for posting schedules and daily reports Petty cash

Petty cash Charged cell phone

Charged cell phone Extra batteries and chargers

Extra batteries and chargers Walkie-talkies

Walkie-talkies Readily available contact information for local police, fire, and permit authorities; local labor guilds; and medical facilities

Readily available contact information for local police, fire, and permit authorities; local labor guilds; and medical facilities Fueled vehicle with navigation system

Fueled vehicle with navigation system