Image Capture Media and Machines

Once you’ve made key creative decisions about aspect ratio and what the visuals should look like, it’s time to decide the best way to capture the movie’s images. In other words, now that you know what the shots should look like, as you learned in the production design and conceptualization phase (Chapter 5), you can determine how to create the shots.

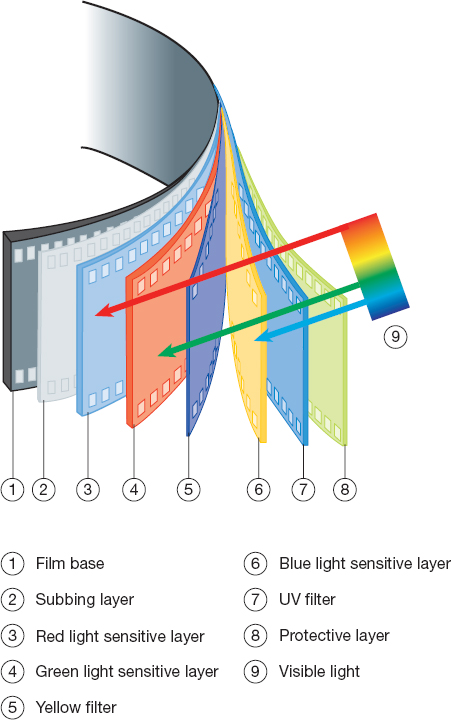

There are two capture media on which images are recorded: digital and film. Each has its own attributes, and each records and stores visual information differently. As illustrated in Figure 6.2, film captures images through a photochemical process. Light rays strike the entire surface of the film and pass through microscopic layers that record three colors: red, green, and blue. Digital media captures its images through an electronic process. Digital cameras currently record images with sensors. The sensors themselves are made up of microscopic photosites that capture photons of light. Since digital sensors are color-blind, red, green, and blue filters (“lenslets”) must be placed over each of the microscopic photosites. The filtered light recorded by each of the photosites is then interpolated and the image is then mathematically reconstructed into full color. Because of the need for electronics to transfer the information from each photosite and build the photographed image, it is not possible for the entire surface of a sensor to capture light. The percentage of total area in which a sensor is sensitive to light is called the fill factor. Photographic film essentially is 100 percent sensitive to light, and therefore has a native fill factor of 100 percent. With digital imagers, there are areas where no light is captured at all because there are no photosites there. The greater the fill factor of an image capture device, usually translates into greater dynamic range.

FIGURE 6.2Film capturing images

The difference between film and digital media, and their corresponding technologies, explains why film can capture more light than digital media can, resulting in dramatically higher dynamic range. It is also one of the reasons why images captured on film and digital media look different from each other. For example, grain, which you see as tiny wavering dots on the screen, may occur in film because of its photochemical process, but grain does not occur naturally in digital; in fact, some digitally shot movies add “grain” as a computer-generated effect to match the look some people expect from movies.

Digital and film motion picture cameras work differently, but they have one thing in common: they are boxes with lenses that focus light onto a medium or device that will capture what the lenses see. Both kinds of cameras take a series of images very quickly, and each image becomes a frame of the finished movie. (To understand why individual still frames make your brain see motion, see Tech Talk: What Are You Seeing?, below.) In addition, their end product is the same—the creation of an image.

STORE WHAT YOU SHOOT

STORE WHAT YOU SHOOT

Whether you’re shooting on film or digital, storing and safekeeping what you’ve shot is of primary concern. Some cinematographers never let the memory cards or exposed film reels out of their immediate control, escorting them to wherever they need to go—whether by ground transportation or plane!

What Are You Seeing?

How do images get onto a screen, and what makes them seem like they’re moving? A single shot is made from many still frames (or still images). When you see a movie in a cinema, your brain is tricked into thinking you are seeing moving images. In fact, you are seeing a series of still images flashed so quickly that they appear to move. These images are being shown at 24 frames per second. This is the long-standing industry standard minimum frame rate for cinematic presentations.

That paradigm is slowly starting to shift, however, as some prominent directors are experimenting with higher frame rates now that new digital camera technologies are capable of shooting at faster speeds, and industry governing bodies are currently engaged in long-term studies regarding the creative impact and technical requirements necessary for making and projecting movies at frame rates higher than 24 frames per second. That is one of many exciting debates about changes and transitions going on in the world of digital cinema right now, and there are exciting new creative possibilities looming as a result. But, for the foreseeable future, 24 frames per second is likely to remain an industry standard, even as other options are worked into the discussion. In any case, frames per second are called fps. With a conventional motion picture projector, a shutter in front of the projector lamp spins around, making light flash through the frames of film. A single frame flashes, then the film advances and the next frame flashes, and so on. Between each frame, there is blackness, but it is so fast your eye does not notice it. A digital projector operates differently, with no “blanking” between the images, but the illusion is achieved the same way, with individual images at 24 fps. A television shows images at 30 fps, and mobile devices show them at lower rates. (Television sets in the United States actually broadcast images at slightly less than 30 fps—there’s a difference of about 1/100th of an fps. That’s not a difference you can see, but you may notice it when you are editing. We’ll cover this in more detail, and tell you what to do about it, in Chapter 11.)

In the case of film, the captured image recorded on film is a negative or reverse of what the actual scene looks like. Open an image in Photoshop, choose the Invert command, and you’ll see what a negative image looks like. Because of the analog photochemical nature inherent in the film process, creating images is a constant workflow of negative to positive and back to negative again, and then back to positive again. This was precisely how motion picture release prints have been made since the mid-1970s. The most valuable film element in a film workflow is that original negative that first recorded the scene in the camera. In the case of digital cameras, the image created is a positive from the start, and stays that way, as it isn’t burdened by the negative/positive workflow of film.

In this book, we define a negative as the original images as they were captured, images that are easy to manipulate; although a negative contains captured images, these images can be changed considerably. For example, from a good negative you can turn day to night, correct mistakes, add backgrounds and other visual effects, or change colors. Digital cameras create what has come to be known as a digital negative that’s stored in a hard drive in a highly manipulable form. (To be considered a negative, the data cannot be in a format that can be easily degraded, such as a JPEG or a QuickTime file.) Film cameras create a physical film negative on a piece of celluloid.

COMPARING SHOTS

COMPARING SHOTS

Compare a movie shot on film with a movie shot on digital—for example, The Dark Knight Rises (2012), which was shot and finished on film, and Man of Steel (2013), which was shot and finished digitally. Can you see aesthetic differences between them in terms of the nature and quality of the imagery? If so, what differences do you detect? Which do you prefer, and why?

The ability to store, archive, and later recall the negative is a topic of much debate and voluminous research. Film negative, properly stored and maintained, has a viable life span of approximately a hundred years. Digital media, however, is not so long-lived. “From MP3 players to cell phone cameras to the Internet, digital technology has made our lives easier, more fun and—online pet videos aside—more productive,” the Academy’s Science and Technology Council wrote in a recent report. “But as anyone who has ever suffered the heartbreak of a hard drive crash or tried to watch home movies recorded in a now obsolete format knows, there is a dark side to storing information digitally.”4 The “dark side” is that digital images have an undetermined life span, and there is no sure way to archive and store them; in fact, many digital images have already been lost forever.5 We’ll explore some possible solutions in Chapter 11.

The concept of the negative is so important that an entire movie is sometimes called a negative, and having a movie is often referred to as “holding the negative” or “having a negative.” No matter how you make your movie, when you are done, you will have a negative, too. Because negatives can be created digitally or on film, let’s start with how most people make them today—with digital cameras.