10.2 Life on the Continental Margins

Describe the ecosystems along continental margins and human influences on those ecosystems.

Life in the oceans is not grouped into biomes, as it is on land. Marine biological interactions are instead referred to as ecosystems, and more locally, as communities of interacting organisms.

Our tour of life in the oceans begins at the margins of continents, where people interact intensively with marine ecosystems. Marine ecosystems on the margins of continents are readily accessible to be seen, enjoyed, used, and influenced by people. These ecosystems, in the order in which they are covered in this chapter, include coral reefs, mangrove forests, seagrass meadows, estuaries, kelp forests, and beaches and rocky shores.

Coral Reefs

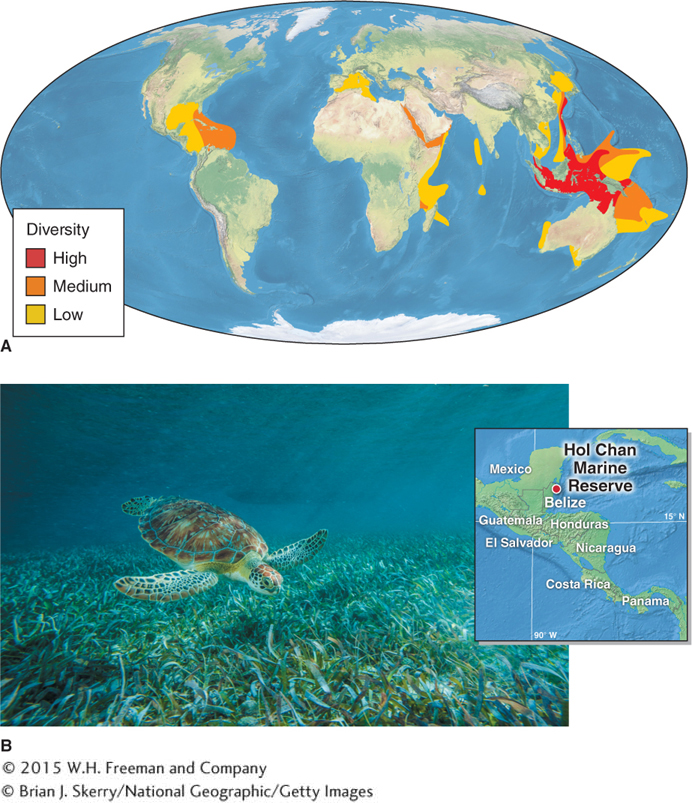

Coral reefs, often called the rainforests of the sea, are one of nature’s greatest displays of life. Coral reefs are the most biodiverse marine ecosystems. There are two broad types of corals: cold-

This section will focus on warm-

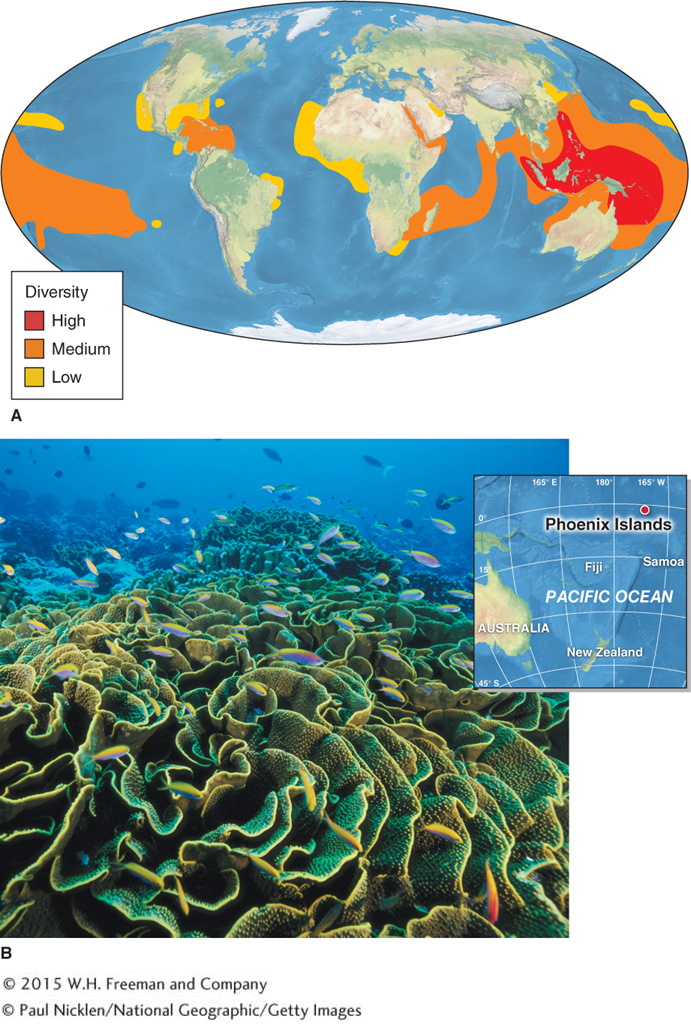

Coral reefs occupy only 0.1% of the area near the ocean’s surface, about 286,000 km2 (110,000 mi2), but they are used by approximately 4,000 species of marine fishes. Scientists are still learning about coral reefs, and perhaps less than 10% of coral reef species have been identified.

Corals look like plants, but they are animals called zooxanthellae, which are related to jellyfishes. There are about 800 known species of hard corals. Most corals share an obligate mutualism with algae (see Section 7.2): The corals filter nutrients from seawater and make them available to photosynthetic algae living within the corals’ tissues. The algae, in turn, provide the corals with carbohydrates and fats.

Corals require clean, well-

Reef-

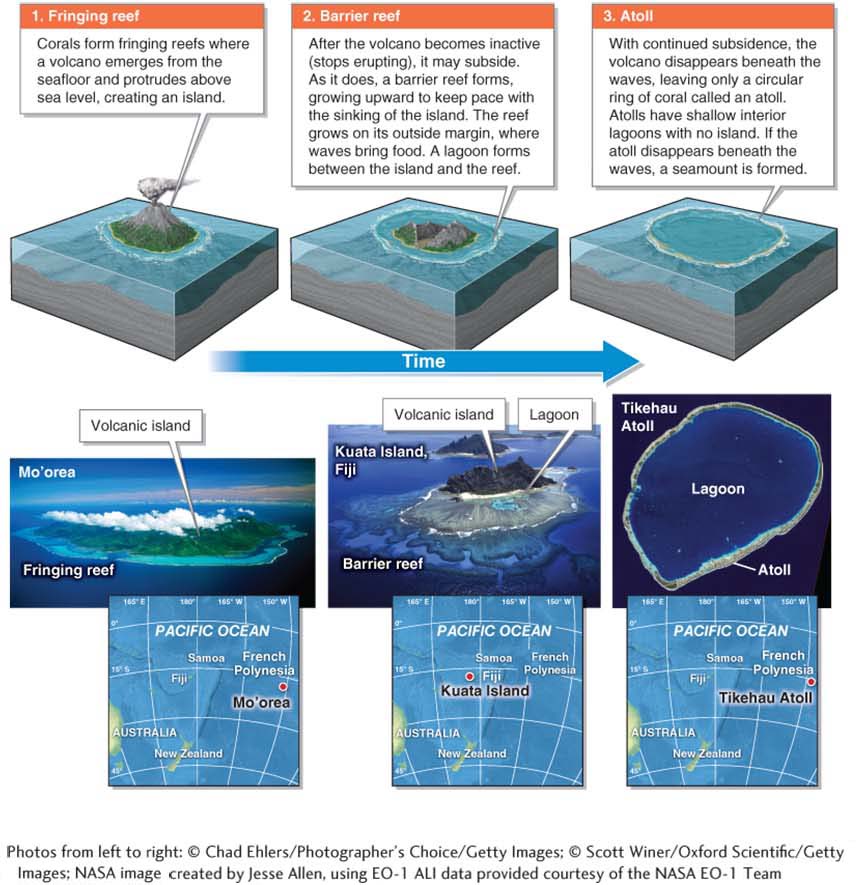

There are three kinds of coral reefs: fringing reefs, barrier reefs, and atolls. A fringing reef forms near and parallel to a coastline. A barrier reef runs parallel to a coastline and forms a deep-

fringing reef

A coral reef that forms near and parallel to a coastline.

barrier reef

A coral reef that runs parallel to the shoreline and forms a deep-

atoll

A ring of coral reefs with an interior lagoon, formed around a sinking volcano.

lagoon

A fully or partly enclosed stretch of salt water formed by a coral reef or sand spit.

Threats to Coral Reefs

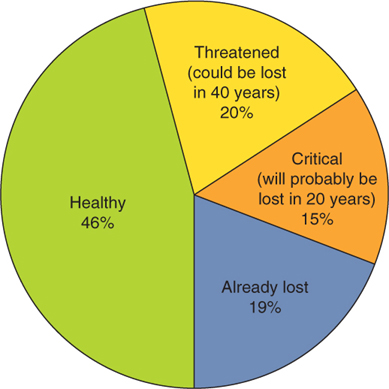

Worldwide, coral reefs are in decline, and their decline points to deeper, global-

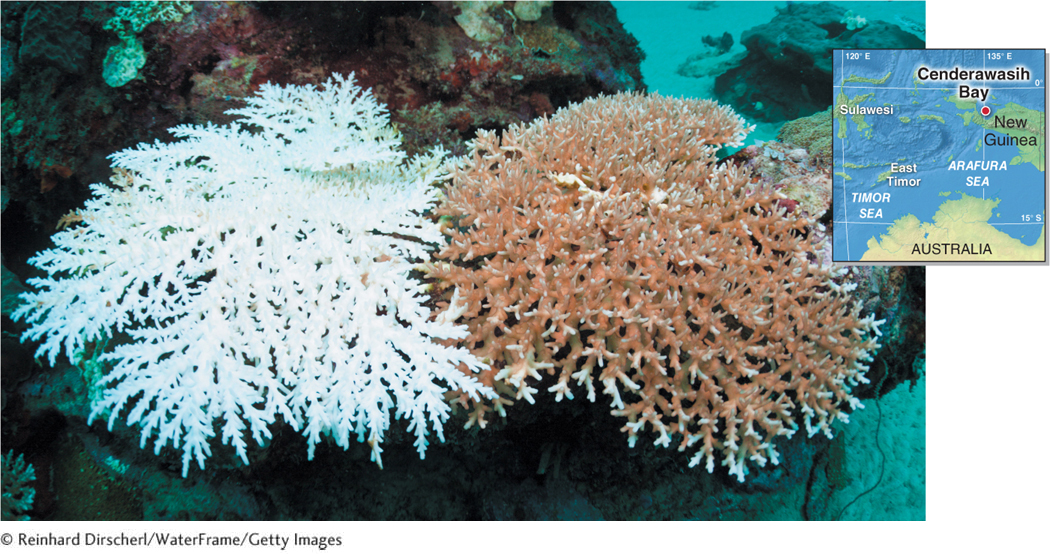

The first sign of trouble for a reef is coral bleaching. Coral bleaching is the loss of coloration in corals that occurs when they have been stressed or have died. When corals become stressed, they expel the algae living within them. The corals then starve because they are unable to produce enough food. Most of the color of corals comes from their algal partners. Once the algae are gone, the corals appear white, as Figure 10.15 shows.

coral bleaching

The loss of coloration in corals caused by the absence of their mutualistic algae, which occurs when they have been stressed or have died.

Coral bleaching events are increasing for a number of different reasons. Warm water associated with strong El Niños (see Section 5.5) brings widespread coral bleaching events. Many other factors also stress corals and trigger bleaching:

Sea surface temperatures above 30°C (86°F). Seawater temperatures are rising in many tropical regions as a result of rising atmospheric temperatures.

Destructive fishing. Fishermen often use cyanide and dynamite to kill and capture fish. These techniques also kill corals.

Coastal development and pollution. Polluted runoff from developed areas stresses corals.

Coastal sedimentation. Increased coastal development reduces soil-

anchoring vegetation and increases erosion of sediments, which settle on and smother corals. Increased ocean acidity. Oceans are absorbing increasing amounts of atmospheric CO2, which is decreasing the pH of seawater.

Diseases carried by viruses or bacteria. Various pathogens (infectious agents like bacteria) are favored in warmer water, and the stressors already mentioned increase coral vulnerability to disease.

In April 2013, research published in the journal Science reported that many coral species have the ability to survive bleaching events and recover more quickly than previously known. Following bleaching events, corals and reef biodiversity are able to rebound within about a decade. This finding is good news because it suggests that, once stressors are reduced, the decline of the world’s coral reefs can be slowed or possibly reversed.

Picture This

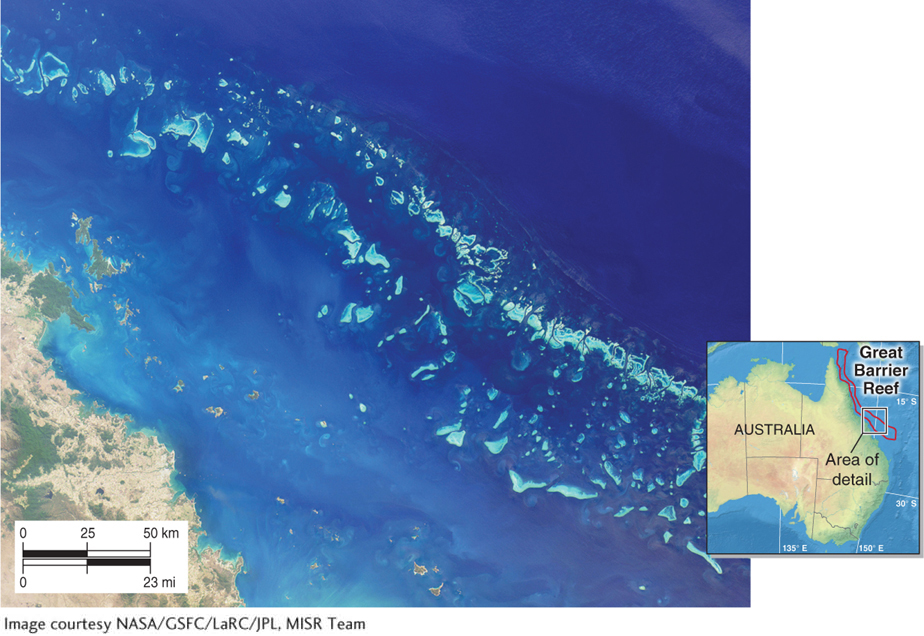

The Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef in northeastern Australia is the largest coral reef system in the world. It is composed of a labyrinth of nearly 3,000 reef formations. The reef stretches more than 2,600 km (1,600 mi), is up to 60 km (40 mi) wide in some places, and covers some 350,000 km2 (135,135 mi2) in area (red area of the inset map). This satellite image shows only the southern portions of the reef off the central Queensland coast.

The Great Barrier Reef possesses some of Earth’s richest biodiversity. It supports 350 to 400 species of corals, 1,500 fish species, 4,000 species of mollusks, some 240 species of birds, 30 whale species, and 6 sea turtle species.

In response to widespread declines in fish populations and poor reef health, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park was established in 2004. Fishing was banned in 32% of the reef’s area. Only two years after the protections were put in place, the reef’s fish biomass doubled and the reefs recovered in the protected areas. About 2 million tourists visit the reef each year, and the park generates over $3.4 billion from ecotourism annually.

Consider This

Question 10.5

Weigh the pros and cons of restricting or banning fishing (or hunting, or collecting) from a natural area to allow wildlife populations to recover.

Question 10.6

Have you ever been an ecotourist? If so, where?

The Value of Coral Reefs

About a half billion people use coral reefs directly or rely on them for their food and economic livelihood. Compounds to fight cancer, HIV, and malaria have been discovered in coral reef species. International tourism in many tropical regions, such as the Caribbean Sea and Hawai‘i, is centered on coral beaches and coral reefs. In the Caribbean Sea alone, coral reefs are estimated to provide roughly $5 billion yearly in the form of tourism, fishing, and food security. Picture This explores the Great Barrier Reef of Australia in the context of tourism revenue.

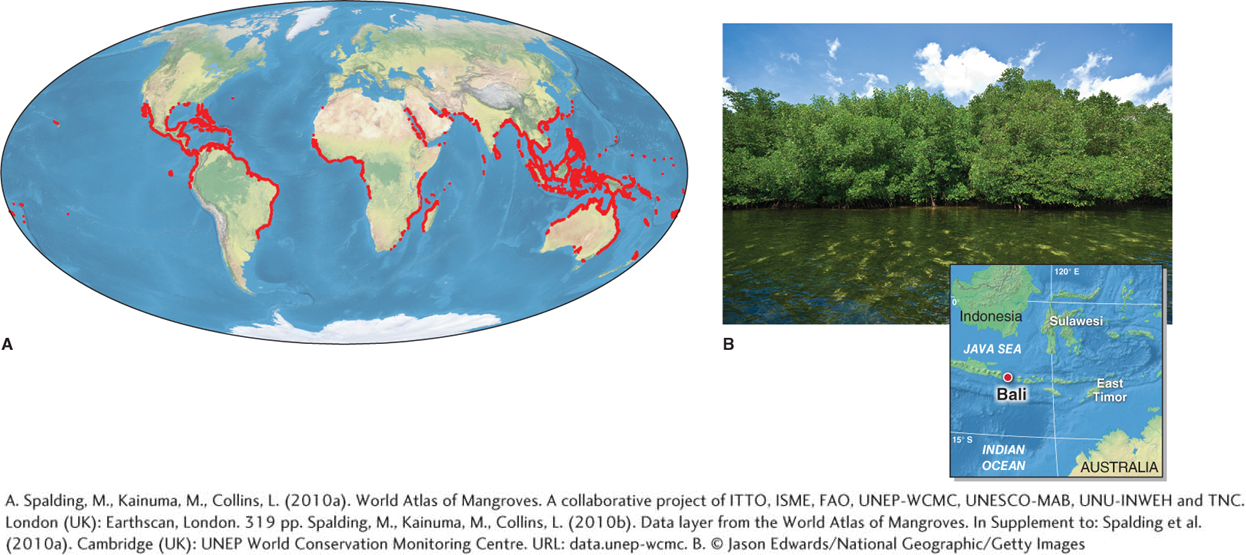

Mangrove Forests

Mangrove forests are ecosystems dominated by saltwater-

mangrove forest

A coastal marine ecosystem dominated by saltwater-

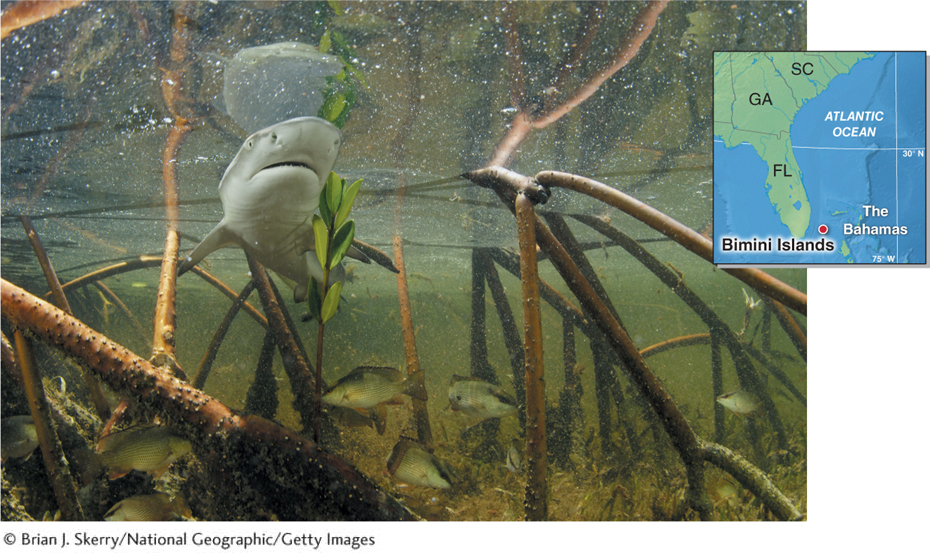

The mud in which mangrove roots grow is almost completely devoid of oxygen. In response, mangrove trees have evolved pneumatophore (air-

Mangrove forests are important ecosystems because they function as nurseries for coral reef fishes as well as many commercial fish species. Marine invertebrates such as oysters, clams, mussels, barnacles, and anemones affix themselves to the roots of mangrove trees. The roots of mangroves trap and hold loose sediments that would otherwise be swept away by currents. The resulting mud in which mangroves grow provides habitat for crabs and sea worms, which in turn attract other organisms, such as predatory fish and birds.

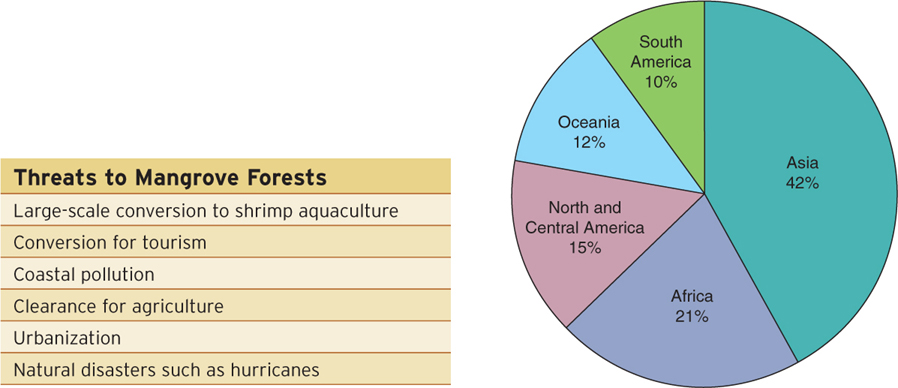

As Figure 10.18 details, there are many threats to mangrove forests. The single most important force of degradation for mangrove forests is shrimp aquaculture (farming). Between 1980 and 2000, more than 30% of the world’s mangrove forests were converted to farms growing shrimp for export to North America, Europe, and Asia.

Half the world’s original mangrove forests are now gone, and these ecosystems are estimated to have dropped from 32 million to 15 million ha (80 million to 37 million acres) as of 2007. About 1% of the remaining mangrove forest area, or 142,000 ha (350,000 acres), is lost each year. At this rate, mangrove forests outside of protected reserves will be gone by the end of the century.

Mangroves are a renewable economic resource for people, and they provide a defense against dangerous surges of water caused by hurricanes or tsunamis (see The Human Sphere in Chapter 14). Coastlines with healthy mangrove forests experience considerably less flooding and erosion compared with regions where the mangrove forests are gone. Protecting mangroves goes hand-

Seagrass Meadows

Seagrass meadows, like mangrove forests, are an often-

seagrass meadow

A shallow coastal ecosystem dominated by flowering plants that resemble grasses.

The plant species we call seagrasses are not true grasses. The seagrasses comprise about 60 different species within four families of flowering plants, all of which look like grasses, with flat and narrow leaf blades. Some common seagrasses are eelgrass (Zostera spp.), turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), and manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme).

Seagrass meadows provide critical habitat for many species of marine life in their juvenile stages of development. Some animals, such as green sea turtles, as well as manatees (Trichechus spp.) and their relatives, dugongs (Dugong dugong), graze on seagrasses. The plants trap sediment, which reduces suspended sediments and improves coastal water quality. Their roots stabilize sediments in coastal areas, reducing coastal erosion.

Several anthropogenic forces, summarized in Table 10.2, are causing losses of seagrass meadows globally. Like coral reefs and mangrove forests, seagrass meadows contribute most to local economies when they are preserved rather than converted to another use. In the Mediterranean Sea and elsewhere, effective efforts to save and restore seagrass meadows have focused on stemming pollution from stream runoff in coastal areas (particularly phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural fields), establishing protected areas, and replanting seagrass meadows that have diminished or have been lost.

|

Coastal pollution |

|

Dredging (deepening of ports and harbors) |

|

Bottom trawling (dragging fishing nets along the seafloor) |

|

Aquaculture |

|

Beach development |

|

Rising sea level |

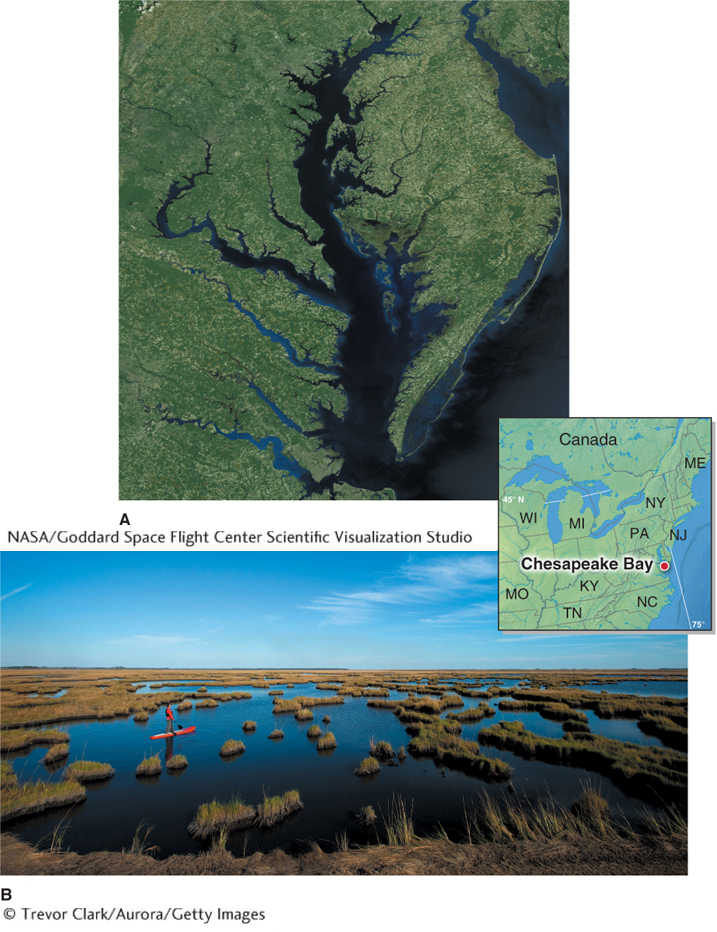

Estuaries

An estuary is a brackish-

estuary

A brackish-

Many large estuaries are about 10,000 years old. They were formed as the great continental ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere (see Section 6.2) began melting 15,000 years ago. The meltwater drained into the oceans and caused sea levels to rise about 85 m (280 ft). Coastal areas were flooded and river-

In the tropics, mangrove forests colonized these drowned river environments. At middle and high latitudes, a variety of salt-

As rivers flow into estuaries, they bring in organic-

Estuaries are important habitats for many kinds of organisms, particularly for the juvenile stages of many fish species. Some 75% of the commercial fish catch in the United States consists of fish that depend on estuaries for at least part of their life cycle. Many bird and mammal species also rely on estuary habitat. Migratory birds use estuaries as rest and feeding stops on their long-

Because estuaries are flat and have calm waters, they make ideal locations for human settlement. Seventy percent of the world’s largest cities, including London, Shanghai, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Boston, and New York City, are located on estuaries (or what were once estuaries). People expand settlements onto estuaries by first filling them in with debris, such as soil or even garbage, then expanding the cities onto the newly created surface.

Because of the heavy human influence on estuaries, they are the world’s most endangered marine ecosystems. Table 10.3 summarizes the threats to estuaries.

|

Heavy industry |

|

Dredging, infilling, and housing development |

|

Coastal pollution |

|

Seawalls |

|

Non- |

Estuaries provide many economic benefits to people. They not only provide shelter for juvenile commercial fish species, but also enhance tourism, recreation (including recreational fishing), and production of shellfish (such as oysters and abalone). Estuaries also absorb wave energy from large storms, such as hurricanes, significantly reducing coastal erosion and property loss. Furthermore, they filter pollutants from rivers before they enter the sea, significantly improving coastal water quality.

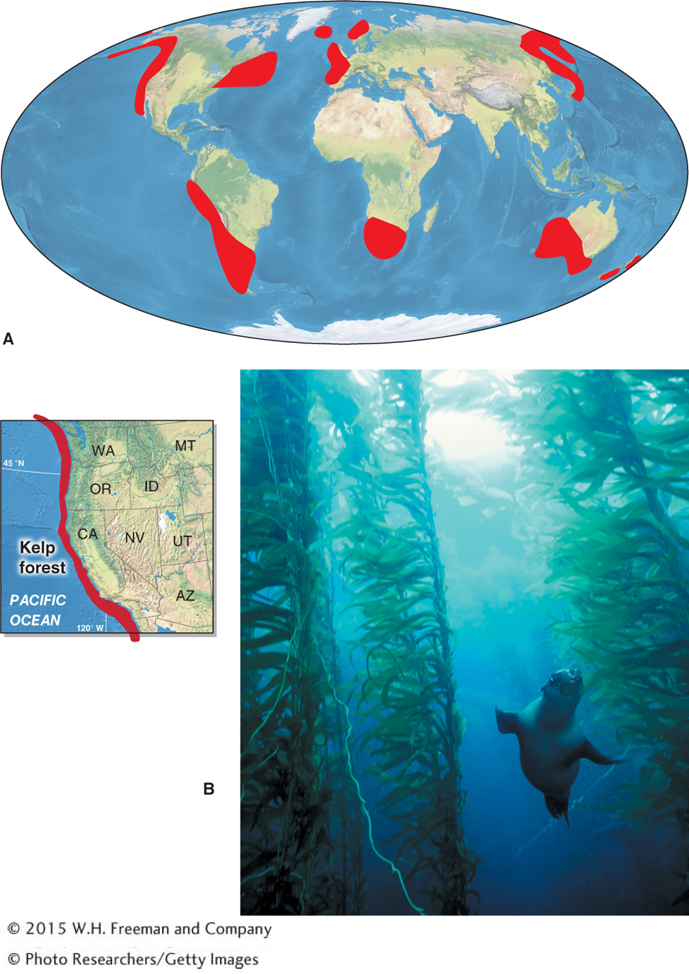

Kelp Forests

Kelp forests are marine ecosystems found in temperate and polar waters where the water temperature does not exceed 20°C (68°F) (Figure 10.21). They are dominated by large algae called kelp. There are three groups of kelp: green kelp (Chlorophyta), tan kelp (Phaeophyta), and red kelp (Rhodophyta). Only tan kelp form kelp forests.

kelp forest

A coastal marine ecosystem dominated by kelp, found where ocean water is colder than20°C (68°F).

Limited to zones with adequate light, kelp forests grow only in water no deeper than 50 m (165 ft). The kelp rely on holdfasts, which resemble roots, but function only to anchor the algae to the rocks. Many kelp grow quickly—

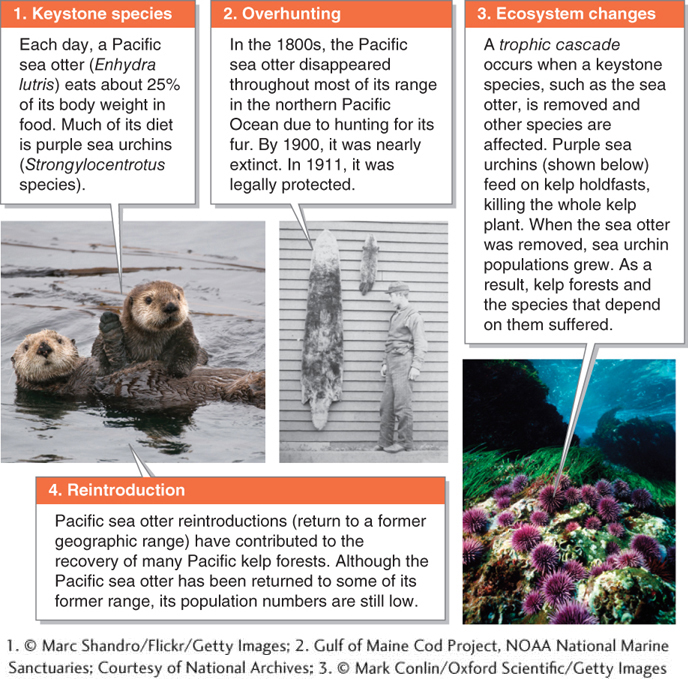

Communities of fish, sea urchins, anemones, sea stars, mollusks, and lobsters inhabit kelp forests. Kelp employ toxins to deter many grazers. Sea urchins, however, can eat kelp, and if their populations increase, kelp forests often suffer declines. Figure 10.22 explores the Pacific sea otter’s role as a keystone species in kelp forests.

Like other coastal ecosystems, kelp forests are vulnerable to threats posed by human activities (Table 10.4). Fortunately, the rapid growth rates of kelp allow them to recover rapidly if degradation pressure stops.

|

Pollution and sediment runoff from streams |

|

Ocean warming caused by climate change and El Niño |

|

Removal of keystone species, such as sea otters |

|

Non- |

|

Harvesting of kelp for food and other products |

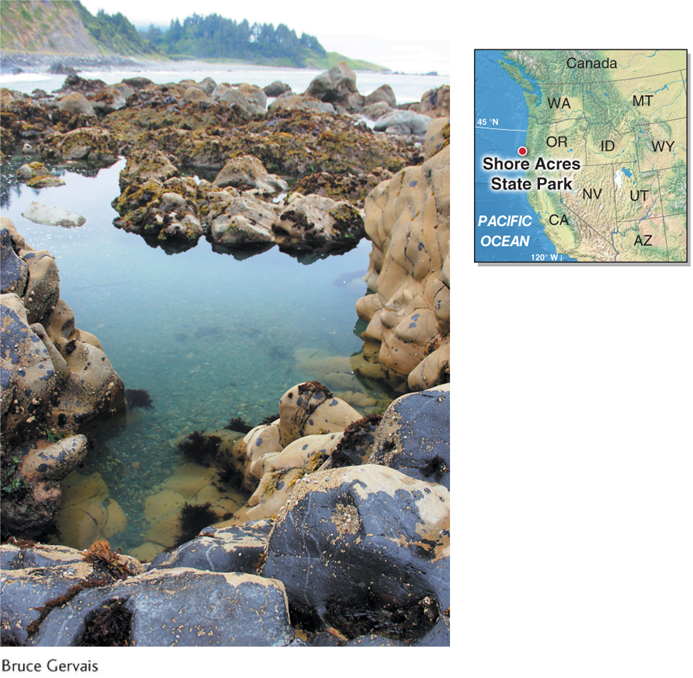

Beaches and Rocky Shores

The coastal ecosystems most familiar to people may be beaches and rocky shores. Most of us have strolled along a beach barefoot or gazed at the horizon from a rocky shore. Because they are exposed to the force of crashing waves and wind, beaches and rocky shores are high-

In general, biodiversity is not particularly high in beach and rocky shore environments, but many organisms live only in these habitats or rely on them during at least part of their life cycle. Shorebirds such as gulls, sandpipers, terns, and pelicans are common on beaches and rocky shores. Marine mammals such as sea lions, seals, and sea otters are found in these environments as well. Sea turtles nest only on warm beaches in the tropics. Human settlement, pollution runoff, and erosion of sand are the most significant threats to beach and rocky shoreline ecosystems (Table 10.5).

|

Conversion to vacation resorts and construction |

|

Pollution runoff |

|

Fishing pressure |

|

Erosion of sand |

|

Non- |