19.3 The Sisyphus Stone of Beach Nourishment

Assess and evaluate the practice of restoring eroded beaches by artificial replenishment of sand.

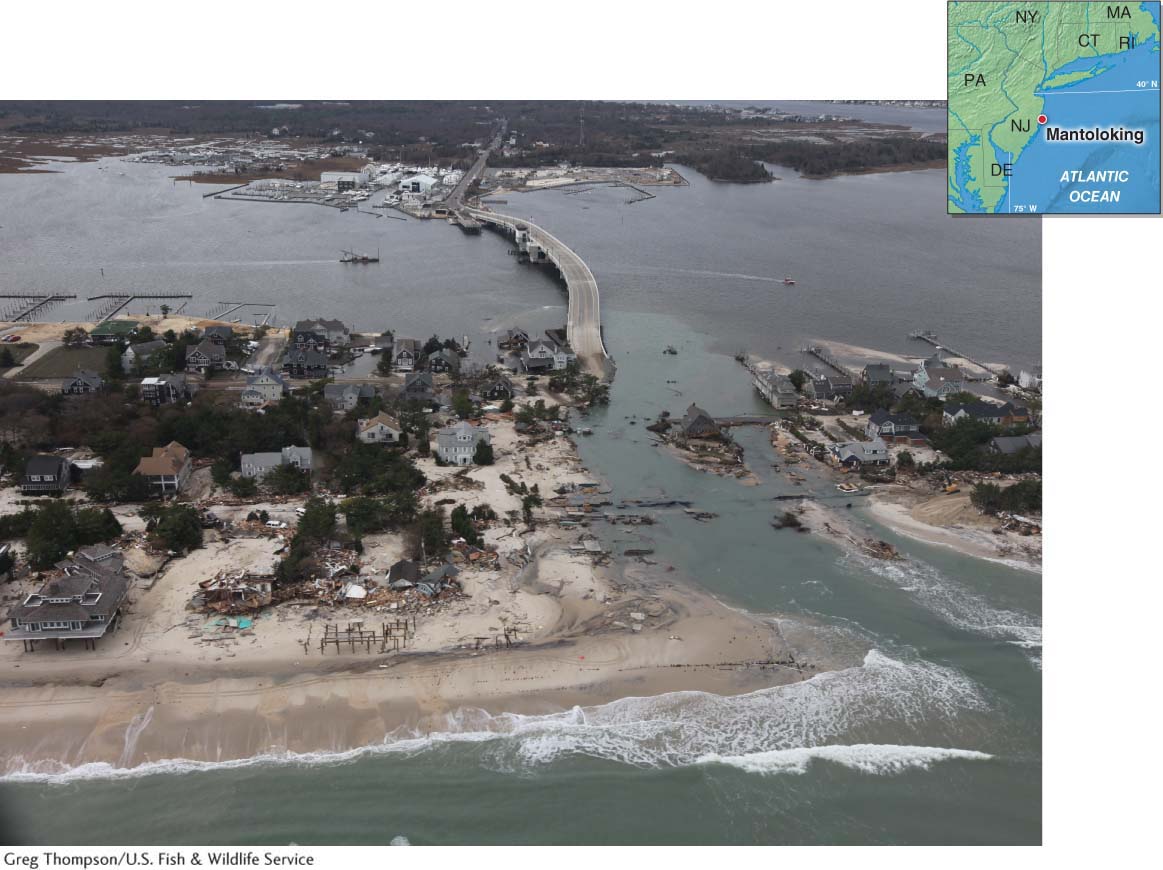

Superstorm Sandy made landfall in New Jersey on October 22, 2012. About 94% of New Jersey’s beaches and backshore dunes, as well as the structures on them, were damaged by the storm surge and waves that Sandy generated. Many of the beaches affected by the storm lost sand (Figure 19.20). Some 60% of New Jersey’s beaches were narrowed from 15 to 30 m (50 to 100 ft).

Beach erosion may occur in a single major storm event, but as we saw in Section 19.2, it may also be a gradual process in which sand is slowly lost over many years. There are three main options available to address the problem of beach erosion: (1) relocation of development away from the beachfront, (2) hard structures such as the groins and seawalls discussed in Section 19.2, and (3)beach nourishment (or beach replenishment): the artificial replenishment of a beach with sand.

beach nourishment

The artificial replenishment of a beach with sand.

Question 19.8

Why is the sand on many beaches artificial?

Beach erosion requires the addition of sand. Sand that is dredged off the coast and added to a beach is considered artificial sand.

Beach nourishment can be used after a single large storm, such as Sandy, has significantly eroded a beach. More often, however, beach nourishment is a routine maintenance process used to keep a beach from losing sand. The most common way to obtain sand is by offshore dredging. A large ship vacuums up sand from the seafloor and pumps it onshore through large metal pipes.

Bulldozers then push the sand into place (Figure 19.21). Sand that is dredged off the coast and added to a beach is considered artificial sand.

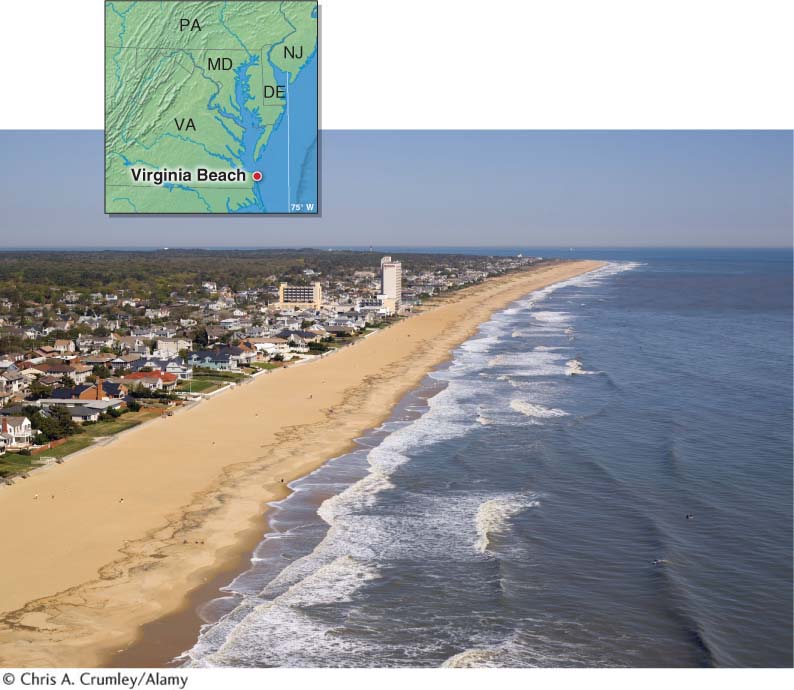

The average lifetime for an artificial beach is five years. Sometimes, the sand lasts less than one year, and sometimes, it persists for a decade. On average, Virginia Beach, Virginia, has been nourished with sand every 1.3 years since 1951. The most recent beach nourishment, in 2013, cost taxpayers $9 million (Figure 19.22).

As we have seen in this chapter, beaches are spatially dynamic landforms. Human activities have changed the dynamics of sand movement along coastlines, such that net erosion is now more common than net deposition for many beaches worldwide. Beach nourishment resets the clock on beach erosion by only a few years—

Proponents of beach nourishment argue that just as the nation’s roads and bridges must be maintained, so must the nation’s beaches. Beaches are a public asset and an important part of the national economy. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers oversees beach nourishment projects paid for by the federal government. The Corps sees beach nourishment as beach maintenance for the common good: The beaches have sand, and the hotels have tourists. The livelihoods of many people depend on vacationers attracted to beaches. The Corps estimates that it has saved $443 million in storm-

Opponents of the practice claim that beach nourishment is an exercise in futility, a Sisyphean task. In Greek mythology, King Sisyphus was made to roll a huge stone up a hill repeatedly for eternity. Just as he was nearly at the top of the hill, the stone would slip and roll back down again, and he would then have to start over. By some estimates, the cost of maintaining beaches in the United States with beach nourishment will be about $6 billion per year by 2020. By the end of the century, the total costs could approach $90 billion. Given its costs, and given that it is only a temporary remedy, is beach nourishment a viable long-

At present, the answer appears to be yes. According to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, the practice will increase in the coming decades. By 2050, southeastern Florida will have completed 100 beach nourishment projects and moved a total of 100 million cubic yards of sand. Many major tourist beaches around the world are experiencing erosion, including beaches in Australia, Hawai‘i, Hong Kong, and Cancún, Mexico. All of them are relying on beach nourishment to maintain their beaches and keep the tourists coming.