10.4 Indirect/Second-Degree Price Discrimination

When to Use It Indirect/Second-Degree Price Discrimination

The firm has market power and can prevent resale.

The firm’s customers have different demand curves.

The firm cannot directly identify which customers have which type of demand before purchase.

We’ve seen how firms with market power can use direct price discrimination to increase their producer surplus above the amount they could earn by charging only a single price. The key is to charge higher prices to customers with relatively inelastic demand and lower prices to those with more elastic demand. However, being able to directly observe a customer’s demand type before purchase (as required with direct price discrimination) is often difficult. A firm might know that its customers have different price sensitivities, but it may not be able to tell to which group any particular customer belongs.

396

indirect price discrimination (second-

A pricing strategy in which customers pick among a variety of pricing options offered by the firm.

Even without this knowledge, a firm can still earn extra producer surplus through price discrimination by using a pricing strategy called indirect price discrimination, also known as second-

There are many different kinds of indirect price-

Indirect Price Discrimination through Quantity Discounts

quantity discount

The practice of charging a lower per-

The most basic type of indirect price discrimination is the quantity discount, a pricing strategy in which customers who buy larger quantities of a good pay a lower per-

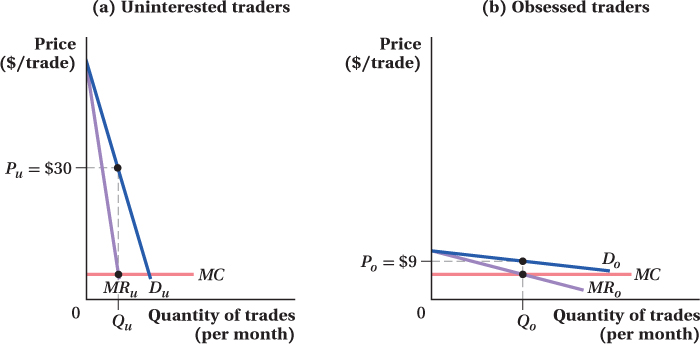

To illustrate the idea, let’s say there are two types of customers of the online brokerage house E*TRADE. One type of customer is not very interested in trading stocks. Because of this, these customers don’t have a big incentive to shop across different online brokers in search of lower commission rates (the fees they pay a brokerage firm to facilitate a trade). Thus, their demands are relatively inelastic with respect to the commission charged. The demand curve for uninterested traders is Du in panel a of Figure 10.6. The other type of customer is obsessed with trading stocks. Because these individuals trade many times each day, they are very sensitive to the commission rate. Thus, their demands are relatively elastic with respect to the commission. The demand curve for these obsessed traders is shown as Do in panel b. The marginal revenue curves for each group are MRu and MRo, respectively. The marginal cost is the same for both groups.

(b) Obsessed traders have a relatively elastic demand curve Do. E*TRADE would like to charge them the lower commission rate Po = $9 per trade. Although E*TRADE cannot directly identify which group any particular trader belongs to, it can set different prices for the two groups using a quantity discount by requiring traders to make at least Qo trades per month to get a reduced commission rate.

E*TRADE would like to charge higher commissions to the uninterested traders with an inelastic demand than it charges the obsessed traders with the more elastic demand. This third-

If E*TRADE could segment the market, it would charge each group Pu and Po per trade, and at those prices, each group would make Qu and Qo trades per month. However, E*TRADE can’t directly assign different commission rates to different traders. And it can’t just offer new customers a choice of whether to pay $30 or $9 commissions no matter how much or little they trade because every customer would choose the cheaper option. What can E*TRADE do to take as much of each trader’s surplus for itself? Rather than offer all customers a $9 per trade commission, E*TRADE can tie that commission rate to a requirement that the customer make at least Qo trades per month. For customers who do not want to make at least Qo trades per month, E*TRADE can offer a $30 per trade commission plan that allows them to trade as little or as much as they’d like in one month.

397

The idea behind this strategy is that an obsessed trader, who demands a high quantity of trades and has a more elastic demand, will choose the $9 plan that requires a purchase of at least Qo trades each month. An uninterested trader, on the other hand, will choose the $30 per trade plan. In other words, traders from both groups will sort themselves into the price and quantity combinations designed for them, even though E*TRADE cannot directly identify either type. This is the essence of any kind of successful indirect price-

Incentive Compatibility The plan to charge uninterested traders a higher commission than obsessed traders is logical, but for such a plan to work well and allow E*TRADE to reap the maximum producer surplus available to it, E*TRADE needs to make sure that the uninterested trader won’t want to switch from her $30/Qu package to the $9/Qo package designed for the obsessed traders. That is, the $9 commission deal can’t be so good that the uninterested trader will make extra trades just to obtain the lower price. E*TRADE has to be sure that the uninterested trader’s consumer surplus is bigger with the $30 per trade package than with the $9 package that requires a purchase of at least Qo trades. The offers need to be internally consistent so that each type of buyer actually chooses the offer designed for it.

398

incentive compatibility

The requirement under an indirect price-

Economists have a term for this type of internal consistency: incentive–

An uninterested trader prefers the $30 package over the $9 package (and she will make this choice if the $30 package gives her greater consumer surplus than the $9 package).

An obsessed trader prefers the $9 package because it offers her more consumer surplus than the $30 package.

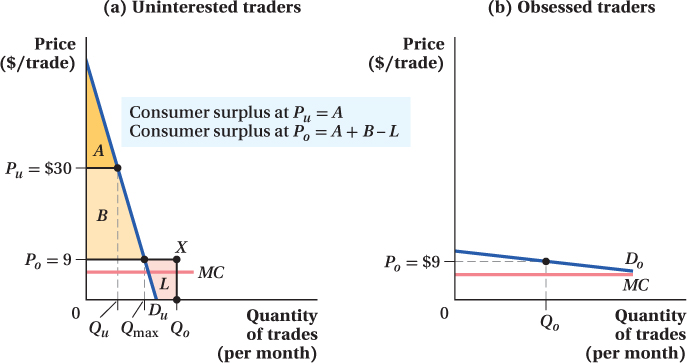

Let’s see whether this set of offers is incentive-

(b) Under the pricing policy for uninterested traders, obsessed traders would have to pay both a higher price (Pu = $30 > Pu = $9) and make fewer trades per month (Qo > Qu). Therefore, the quantity discount is incentive-

Finding the uninterested trader’s consumer surplus for the $9 package offer is a bit trickier. The first thing we need to do is put the $9 package’s price and quantity combination in the diagram showing the demand for trades of an uninterested trader. Call this point X, as shown in panel a. Notice that point X lies above the uninterested trader’s demand curve. That means if an uninterested trader were to make trade number Qo (at a commission of $9), she would actually lose consumer surplus by doing so. At a price of $9, an uninterested trader really only wishes to purchase Qmax trades, the quantity demanded at that price.

399

The fact that Qmax is less than Qo implies that the uninterested trader’s willingness to pay for the trades between Qmax and Qo is lower than the $9 she would have to pay for them. In fact, all trades for which her demand curve (which indicates her willingness to pay) lies below $9 will result in a loss of consumer surplus. In panel a, these surplus-

Comparing the uninterested trader’s consumer surpluses from the two offers, we can now see that she will choose the $30 per trade offer over the $9 package offer if

Area A > area A + area B – area L

0 > area B – area L

Area B < area L

That is, an uninterested trader will take the offer designed for her ($30 per trade) if the extra consumer surplus she would obtain from the lower commission rate (area B) is smaller than the loss she suffers from having to buy a larger quantity than she would have otherwise at the lower offered price (area L).

For uninterested traders, we have outlined under what conditions the offers are incentive-

We saw that an uninterested trader also faces a higher price and lower quantity if she takes the $30 per trade offer instead of the $9 package. So, why isn’t an uninterested trader automatically worse off by taking the $30 offer, as is an obsessed trader? The reason is that if an uninterested trader faced a price of $9 per trade but got to choose how many trades she made, she would never choose to make Qo trades. She would only choose to make Qmax, the quantity of trades demanded at a price of $9 per trade. Any trades between Qmax and Qo destroy consumer surplus for an uninterested trader because the price is higher than her willingness to pay. It is the potential consumer surplus-

400

figure it out 10.3

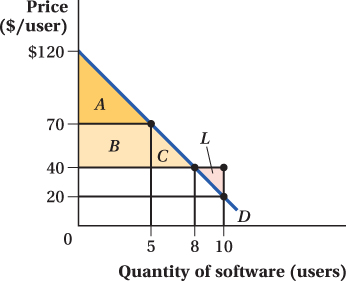

Suppose you are a pricing analyst for MegaDat Corporation, a firm that recently developed a new software program for data analysis. You have two types of clients who use your product. Type A’s inverse demand for your software is P = 120 – 10Q, where Q represents users and P is in dollars per user. Type B’s inverse demand is P = 60 – 2Q. Assume that your firm faces a constant marginal cost of $20 per user to install and set up this software.

If you can tell which type of buyer is buying the product before a purchase is made, what prices will you charge each type?

Suppose instead that you cannot tell which type of buyer the client is until after the purchase. Suggest a possible way to use quantity discounts to have buyers self-

select into the pricing scheme set up for them. Determine whether the pricing scheme you determined in part (b) is incentive-

compatible.

Solution:

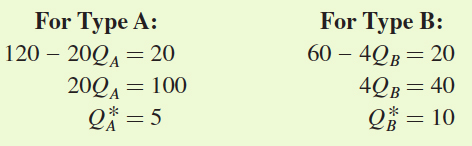

To maximize profit, set MR = MC for each type. Therefore, we first need to solve for the marginal revenue curves for each type. Because we have linear inverse demand curves, we know that the MR curves will have the same vertical intercept but twice the slope. This means that MR = 120 – 20Q for Type A buyers and MR = 60 – 4Q for Type B buyers. Now set MR = MC to find the profit-

maximizing quantity for each type:

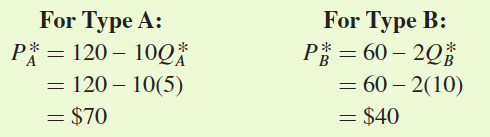

At these quantities, the prices will be

The firm could charge $70 per user for a package where the buyer can purchase any quantity she wishes and a price of $40 for any buyer willing to purchase 10 or more units.

This plan is incentive-

compatible for Type B users. They are willing to continue to purchase Q = 10 at a price of $40 each. For a Type A consumer, we need to consider the amount of consumer surplus she receives under each scheme. We can do this with the help of a diagram showing the Type A demand curve and the two prices, $70 and $40.

At a price of $70, a Type A buyer would choose to purchase 5 units. Consumer surplus would equal area A, the area below the demand curve but above price.

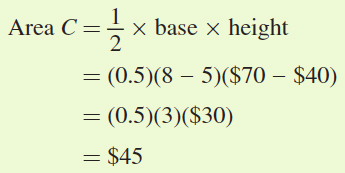

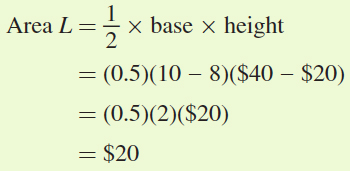

If a Type A buyer were to opt to purchase the other package (10 units at a price of $40 each), her consumer surplus would be the area above the price and below demand (areas A + B + C), but she would also lose consumer surplus because she would be buying units that she values less than the price of $40. This would be area L in the diagram.

Thus, opting for the quantity discount would change the Type A buyer’s consumer surplus by area B + area C – area L. The $40 10-

unit package would be incentive- compatible only if area L > area B + area C. Let’s calculate those values: Area B = base × height

= (5)($70 – $40)

= (5)($30)

= $150

To calculate area C, we need to determine the base of the triangle. This means that we need to know the quantity at which the Type A buyer’s willingness to pay is exactly $40:

P = 120 – 10Q

40 = 120 – 10Q

10Q = 80

Q = 8

401

Therefore, area B + area C = $150 + $45 = $195.

To calculate area L, we need to be able to determine the height of the triangle. To do so, we need the price at which a Type A buyer would be willing to purchase Q = 10 units:

P = 120 – 10Q

= 120 – 10(10)

= 120 – 100

= $20

So, we know that area B + area C = $150 + $45 = $195 and area L = $20.

Because area A + area B > area L, the $40 10-

unit pricing scheme is not incentive- compatible for Type A buyers. These buyers will want to receive the quantity discount and will purchase 10 units at a price of $40 each. Thus, this pricing scheme would not be successful at making the buyers self- select into the pricing scheme established for their types.

Indirect Price Discrimination through Versioning

versioning

A pricing strategy in which the firm offers different product options designed to attract different types of consumers.

Airline tickets are a classic example of what we call versioning—offering a range of products that are all varieties of the same core product. Airlines have a group of business travel customers who are not very sensitive to prices and a group of leisure travelers who are highly sensitive to price. Airlines want to charge different prices to the two passenger groups, but they can’t tell who is flying on business when a customer buys a ticket. So, the airlines instead offer different versions of the product (tickets on a given flight) available at different prices. The cheaper version, with many restrictions, is intended for leisure travelers who buy generally well in advance of the travel date, stay over a Saturday night, and book a round-

For this scheme to work, the airlines need to make sure the prices of each version are incentive-

402

Versioning and Price-

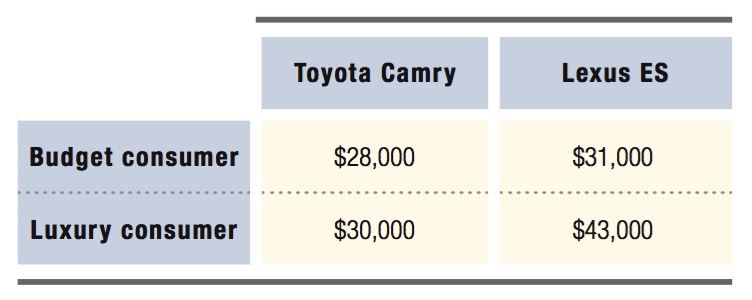

Consider the example of an automaker like Toyota, which sells a lot of midsize sedans. Some of Toyota’s buyers in this segment will not be very price-

For example, Toyota makes the Camry, one of the highest-

While those extra options raise Toyota’s marginal cost of producing an ES, it’s unlikely that this increase in marginal cost would amount to $12,000 per car. Toyota charges more than the cost difference because the different versions split its customers into groups based on their price sensitivities. The Lexus group has less elastic demand, so Toyota’s markup over marginal cost can be higher, just like the Saturday-

To be incentive-

Notice that both consumers believe the Lexus is worth more than the Camry. It’s not that Toyota has made a version that one group likes and the other doesn’t. The budget consumers value a Lexus more than a Toyota, but not very much more: $31,000 versus $28,000. The luxury consumers, however, value the ES a lot more than the Camry: $43,000 versus $30,000.

If Toyota prices the Camry at $26,000 and the Lexus ES at $38,000, the budget consumers get $2,000 of consumer surplus from buying the Camry and –$7,000 from buying the Lexus (it costs more than they value it), so they will buy the Camry. The luxury consumers get $4,000 of surplus from buying the Camry and $5,000 from the Lexus, so they go with the Lexus. Each group chooses the version designed to take advantage of the nature of their demand curves. That means these prices are incentive-

If Toyota priced the Lexus at $40,000 rather than $38,000, the budget consumers would still buy the Camry. The status consumers, however, would get more consumer surplus from buying the Camry ($4,000) than from buying the Lexus ($3,000), so they would also decide to buy the Camry. That $2,000 price increase for the Lexus would cause Toyota to lose $12,000 (losing a sale of a $38,000 Lexus at the old price for a $26,000 Camry instead) for each luxury consumer. By charging the group with the less elastic demand too high a price, Toyota would not be setting incentive-

403

One detail that is important to note is that it is not the mere existence of customers with inelastic demand that allows Toyota (or any other firm) to indirectly price-

There is virtually no limit to the kinds of versioning a company can implement to get its customers to self-

Indirect Price Discrimination through Coupons

Coupons are also a form of indirect price discrimination. Retailers would like to charge shoppers who have less elastic demands more for products while setting a lower price for consumers who are more sensitive to price. Again, however, they have no way of directly identifying and separating these different groups when they buy, so they have to get the groups to do it themselves. Coupons are a device they use to do so.

The key to the way coupons work is that the people who go to the trouble of using coupons—

That’s why coupons usually aren’t right next to (or especially already attached to) the items to which they apply. If they were, it would be easy for even the shoppers with less elastic demand to use them, and everyone would receive the discount. The fact that firms require consumers to expend a little effort to use a coupon is not coincidence; it is exactly the point. Mail-

404