17.4 Public Goods

public good

A good that is accessible to anyone who wants to consume it, and that remains just as valuable to a consumer even as other people consume it.

So far in this chapter, we have looked at market failures in which markets end up with an inefficient level of output as a result of externalities or unclear property rights. There is another type of good for which markets can fail to deliver the socially optimal level of output. Public goods are goods (such as national defense, a fireworks display, or clean air) that are accessible to anyone who wants to consume them and that remain just as valuable to the consumer even as other people consume them. For example, when you watch a fireworks display from your backyard, it makes no difference if you are the only person watching the display or if all of your neighbors are watching the fireworks, too. And, the individuals putting on the fireworks display can’t stop people from watching it, even if they wanted to. As a result, public goods have distinctive properties that make it difficult for markets to deliver them at efficient levels. Note that a public good is not necessarily provided by a government, although governments often provide public goods because private markets may provide too few of them.

Public goods are similar in some ways to positive externalities: They can provide external benefits to individuals other than those who purchase them. For example, if you host a fireworks display, you may not consider the benefits received by your neighbors when making your purchases. This leads to an output that is smaller than is socially optimal because the full benefits of the fireworks display are not considered. Put simply, if the true social benefits were taken into account, there would be more (and perhaps more elaborate) fireworks displays.

nonexcludability

A defining property of a common resource, which means that consumers cannot be prevented from consuming the good.

Public goods have two important properties. One is that they are nonexcludable, which means all people who want to use the good have access to it. They cannot be prevented—

nonrival

Defining property of a public good that describes how one individual’s consumption of the good does not diminish another consumer’s enjoyment of the same good.

private good

A good that is rival (one person’s consumption affects the ability of another to consume it) and excludable (individuals can be prevented from consuming it).

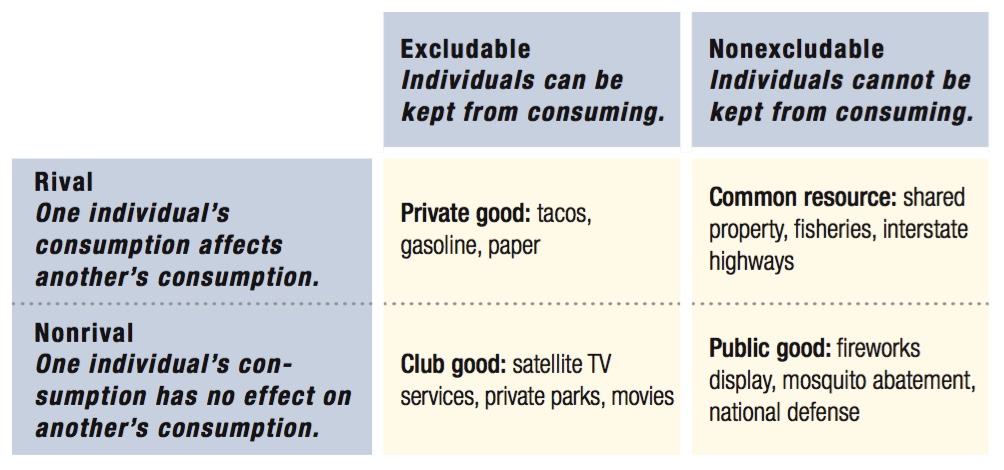

The second property that public goods have is that they are nonrival, meaning that one person’s consumption of the good does not diminish another consumer’s enjoyment of the same good. (A different way to think of a good being nonrival is that the marginal cost of providing the good to yet another consumer is zero.) For example, a TV weather forecast is a nonrival good because the value of the forecast to a consumer is unaffected by the number of individuals also watching the same forecast. The fact that your neighbor watches the forecast (or hears it on the radio, or reads it online or in a newspaper) does not in any way diminish or eliminate the utility you derive from receiving the information. Any good that many people can consume independently without using it up or degrading it is a nonrival good. In contrast, if a consumer buys a rival (regular) good, then someone else cannot buy that exact good. For example, if you are eating a taco, another person cannot eat that same taco. Because the taco is also excludable (a person can be kept from consuming it), it is a private good. Table 17.1 shows the different types of goods that exist categorized by rivalry and excludability.

677

An example of a rival, excludable good is a gallon of gasoline. Because the gasoline is rival, another person can’t consume the same gallon you bought. Gasoline is also excludable because producers can keep you from consuming the gasoline unless you purchase it.

common resource

A special class of good that is rival but nonexcludable; an economic good whose value to the individual consumer decreases as others use it and that all individuals can access freely.

A special class of good that is rival but nonexcludable is a common resource. (Common resources can suffer from a special and often damaging type of externality called the tragedy of the commons, which we discuss in more detail later in this section.) An example of a common resource is the stock of a particular fish, like sturgeon in the Caspian Sea (which are a valuable source of caviar). This good is rival because fish that are caught by one boat cannot be caught by another. However, this good is nonexcludable because it is virtually impossible to stop someone from fishing if she wants to.

club good

A good that is nonrival and excludable.

An example of a nonrival good that is excludable is a satellite TV broadcast of a football game. This good is nonrival because anyone can receive the satellite transmission without taking away the ability of other consumers to watch. However, this good is excludable because consumers must pay a subscription fee to receive the show’s unscrambled signal. Nonrival, excludable goods are sometimes referred to as club goods.

pure public good

A good that is both nonrival and nonexcludable.

An example of a nonrival, nonexcludable good is mosquito abatement, which is often performed by spraying public waterways with pesticides. This good is nonrival because one person’s enjoyment of a mosquito-

free environment does not impact another person’s enjoyment of the same. And, because getting rid of mosquitos helps everyone regardless of who paid for it, mosquito abatement is also nonexcludable. Goods that are both nonrival and nonexcludable are sometimes called pure public goods.

678

The Optimal Level of Public Goods

Before we can see why markets provide inefficient levels of public goods, we have to define what the efficient level of output is for these types of goods. It’s a little different from the efficiency conditions we’ve discussed before.

Efficiency generally occurs when a market produces the quantity for which the marginal cost of producing the good just equals the marginal benefit society receives from the good. For a competitive market without externalities, that quantity is also where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded. As we saw earlier in this chapter, in markets with externalities present, we need to be sure that all external costs and benefits are considered when determining the efficient output. Efficiency in these markets thus occurs at the output for which social demand (which measures social marginal benefit) is equal to social marginal cost.

total marginal benefit

The vertical sum of the marginal benefit curves of all of a public good’s consumers.

With public goods, the marginal benefit from the good is not the benefit for just one consumer because more than one person can consume the good simultaneously. A public good is nonrival, so to value the good, we have to add the marginal benefits of everyone who consumes it. Put differently, a public good’s total marginal benefit curve is the vertical sum of the marginal benefit curves of all its many consumers. This total marginal benefit (MBT) is what equals marginal cost when a public good is being provided at its optimal level. In equation form, the total marginal benefit is written

MBT = ΣMBi

The summation symbol Σ denotes that the good’s marginal benefits are added over all consumers (whom we’ve indexed with i) of that good.

There is no “sum of marginal costs” condition because the cost of producing a public good is just like the cost of producing any other good. While a public good is simultaneously consumed, there is nothing in its definition that implies it is simultaneously produced. Whether made by an individual, a firm, or a government, the marginal cost of a good is the same no matter if that good is a public or standard private good.

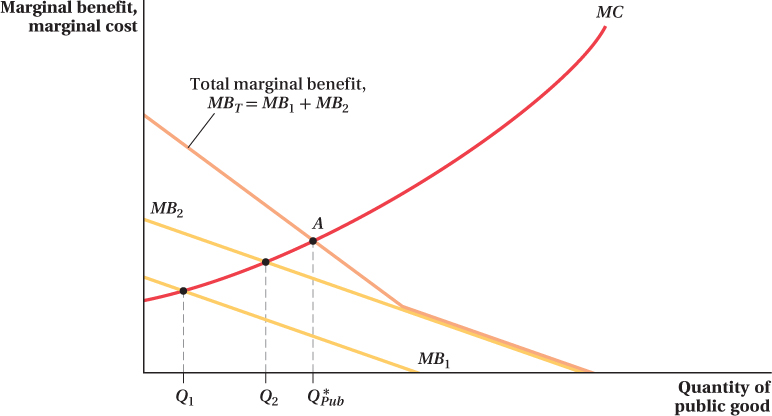

Figure 17.9 shows the public goods efficiency condition for a simple example in which the public good is consumed by two people. The marginal benefit curves of each person are illustrated in the figure as MB1 and MB2. The total marginal benefit of the public good, shown as curve MBT, is the vertical sum of the individual marginal benefit curves. MC is the marginal cost of producing the good.

Efficiency requires that the public good be provided at point A, where MBT = MC, with a quantity of Q*Pub. It’s important to realize that this is the quantity of the public good that both individuals consume. Because it is nonrival, they don’t have to split Q*Pub between them. They consume Q*Pub units of the good simultaneously.

Why isn’t this efficiency condition achieved in the private market? For the same reasons we saw in markets with externalities, the free market is going to encounter a problem providing the right level of public goods. The market facilitates private exchanges until a good’s private marginal cost equals individuals’ private marginal benefits. However, that is not where the combined marginal benefits of multiple consumers equal the good’s marginal cost. If individuals could buy the public good themselves at marginal cost, each would buy the quantity at which her own marginal benefit equals its marginal cost. Looking at Figure 17.9 again, Person 1 would buy Q1, where MB1 = MC. Similarly, Person 2 would buy Q2.

679

Therefore, although both individuals would be willing to pay for some quantity of the public good, neither would by herself pay for the efficient quantity because her individual marginal benefit is less than the joint marginal benefit. The inefficiency arises in a way that is similar to how inefficiency arises with a positive externality: Individuals paying privately for a public good don’t consider everyone else’s benefit from the good. This is one reason why private markets fail to produce the efficient quantity of public goods. Left to their own devices, private markets don’t supply enough national defense, mosquito abatement, clean air, fireworks displays, and the like.

free-

A source of inefficiency resulting from individuals consuming a public good or service without paying for it.

In addition to not taking into account the total marginal benefit of the good and thus having less of it available than is socially optimal, the free-

figure it out 17.4

Dale and Casey are neighbors in a rural area. They are considering the joint installation of a large fountain near their joint property line so that each can enjoy its beauty and also improve the value of his property. Dale’s marginal benefit from the fountain is MBD = 70 – Q, where Q measures the diameter of the fountain (in feet). Casey’s marginal benefit from the fountain can be represented as MBC = 40 – 2Q. Assume that the marginal cost of producing the fountain is constant and equal to $80 per foot (in diameter).

Find an equation to represent the total marginal benefit of the fountain.

What is the socially optimal size of the fountain?

Show that if either Dale or Casey had to build a fountain by themselves, neither would find even the smallest fountain worth building.

Solution:

The total marginal benefit is the vertical summation of Dale’s and Casey’s individual marginal benefit curves:

MBT = MBD + MBC = (70 – Q) + (40 – 2Q) = 110 – 3Q

The socially optimal size of the fountain occurs where MBT equals the marginal cost of producing the fountain:

MBT = MC

110 – 3Q = 80

3Q = 30

Q = 10

The optimal size of the fountain is 10 feet in diameter.

Dale’s marginal benefit is MBD = 70 – Q. If the smallest possible fountain was zero feet in diameter (Q = 0), Dale’s marginal benefit would only be $70, while the marginal cost would be $80. Therefore, Dale would not find even the smallest fountain to be worth the cost. Likewise, the marginal benefit of a zero-

foot fountain for Casey will be MBC = 40 – 2Q = $40, which is also less than the $80 marginal cost.

680

Solving the Free-Rider Problem

A common solution to the free-

681

Other solutions are also possible. Beneficiaries of a public good can form an organization that compels members to pay their share of the public good’s costs. The tricky issue in such situations is convincing potential members to voluntarily form a group that will compel them to pay for something they’d rather not pay for at all. Condo owners, for example, often form a condo association to pay for maintaining a pool and other common areas because free-

As economist Mancur Olson pointed out in 1965, the likelihood of solving the free-

It’s important to realize that the benefit per member of a public good might not be closely correlated with the total benefit of the good. It’s quite possible that a public good that would offer an enormous total benefit may not end up being provided because the size of its potential group is also really large, making the average benefit per person too small to overcome free-

The Tragedy of the Commons

tragedy of the commons

The dilemma that common resources create: Because everyone has free access, the resource is used more intensively than it would if it were privately owned, leading to a decline in the value of the resource for everyone.

A common resource (a type of public good that is rival but nonexcludable) isn’t a pure public good, but it presents a similar kind of inefficiency called the tragedy of the commons. The concept of the “tragedy” comes from the dilemma that common resources create: Because everyone has free access, the resource is used more intensively than it would if it were privately owned. This leads to a decline in the value of the resource for everyone.

A reservoir of water, public forests, public airwaves, and even public restrooms are all examples of common resources. The key element is that the common resource is nonexcludable: Anyone can use or take from it, and those who use it cannot be monitored easily. Because access to the resource is shared by all comers, common resources are also called common-

We can think of the tragedy of the commons as a problem caused by a negative externality. No single user takes into account the negative externality she imposes on others by using the common resource, leading everyone to consume too much of it. The externality involved with a common resource arises because of the combination of open access and depletion through use. When deciding how much of the common resource to consume, everyone considers only her own cost of use. But, this use depletes the resource for all other users. Because individuals don’t consider the cost they impose on others when making their decisions about how much of the common resource to consume, they end up using too much of the resource. And, because everyone accessing the resource creates this same externality with her own use, the total utilization of the resource is above the socially optimal amount. This outcome is analogous to the market quantity being higher than the efficient level in our earlier negative externality examples. Without controls, too much water is extracted from aquifers, fishing grounds are overfished, too many trees are cut on public lands, too many communications devices jam the airways, and so on.

682

FREAKONOMICS

Is Fire Protection a Public Good?

In September 2010 a small trash fire sparked a fire at a house just outside of South Fulton, Tennessee. Firefighters rushed to the scene. But instead of putting out the blaze, the firefighters stood by and simply let the house burn to the ground.*

* “No Pay, No Spray: Firefighters Let Home Burn,” October 6, 2010, http:/

Why didn’t they do anything? To understand why, we have first to understand how the South Fulton fire department is funded. Residents in the city of South Fulton pay taxes to fund the fire department, so the city itself has fire coverage. It’s inefficient for the rural areas outside South Fulton to have their own fire department. So, the South Fulton fire department offers fire coverage—

It turns out, however, that South Fulton Fire Chief David Wilds thinks like an economist. To the noneconomist, it might seem that the neighborly thing to do would be to fight any rural house fire, regardless of the fee. But, the local fire chief recognized an important fact: Without the enforced yearly fee, firefighting is a nonexcludable good; that is, no individual or family could be kept from enjoying the fire protection. The time and effort the fire department put into preventing fires, fighting those that do arise, and watchfully waiting when there isn’t a fire benefit everyone in an area, whether it’s their house on fire or not.

Homeowners would like to enjoy the benefits of this nonexcludable good but only actually pay if and when their house catches on fire. (This is also related to the adverse selection problem in insurance markets we discussed in Chapter 16.) That sort of payment arrangement wouldn’t provide much of a budget for the fire department to work with, however. So, the department requires all rural homeowners to pay their fire coverage service fee ahead of time if they want the fire department to answer their calls.

We know why the firefighters didn’t put out the blaze—

The strong economic rationale behind this fire department’s policy doesn’t mean it hasn’t taken a lot of heat for its decision. Letting the house burn garnered Fire Chief Wilds national attention, and the media did not appreciate the economic logic of his decision. In response to this public uproar, it only stands to reason that Wilds would succumb to political pressure and abandon the policy. If you think that’s what happened, then you underestimated Wilds. Just a little over a year later, he allowed another house to burn to the ground, ensuring his spot in the Freakonomics Hall of Fame.

683

The Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, for example, is a surreal landscape full of fallen ancient trees that have been petrified into rock. It is a common resource for everyone to enjoy, yet many visitors steal small pieces of petrified wood to keep as a souvenir. The parks service estimates that it loses about 12 tons per year in theft. Each thief thinks, “I can take just a small piece . . . it won’t make any difference,” and doesn’t take into account that removal of that one piece reduces the value of the park for others. Without controls—

In some cases, the consequences of this overuse can be severe: Instead of preserving a sustainable fishing stock, for example, overfishing can easily drive an entire population of fish to extinction. It’s not that fishers prefer to drive their prey to extinction; in fact, they prefer to have a steady supply available. But, the overfishing happens because of the externality and the open access to the fishing stock.

Remedies for the Tragedy of the Commons Because the tragedy of the commons is just a special form of negative externality, any of the solutions we described in the previous section can be used to try to fix it, and they are, in fact, employed in many actual situations. For example, governments use price-

Another way to fix the tragedy of the commons externality involves defining property rights and facilitating negotiation among those who share the common resource. For the airwaves, for example, the government auctions off spectrum and says that whoever buys the spectrum is the only one allowed to broadcast at that frequency. Granting sole control of one part of the resource to one party eliminates the negative externality. The person in control gets all the benefit and pays all the cost of using the resource, so she doesn’t have an incentive to overuse it.