6.3 Production in the Long Run

In the long run, firms can change not only their labor inputs but also their capital. This difference gives them two important benefits. First, in the long run, a firm might be able to lessen the sting of diminishing marginal products. As we saw above, when capital is fixed, the diminishing marginal product limits a firm’s ability to produce additional output by using more and more labor. If additional capital can make each unit of labor more productive, then a firm can expand its output more by increasing capital and labor inputs jointly.

Think back to our example of the coffee shop. If the shop adds a second worker per shift when there is only one espresso machine, the firm won’t gain much additional output because of the diminishing marginal product of labor. Hiring still another worker per shift will barely budge output at all. But if the firm bought another machine for each additional worker, output could increase with little drop in productivity. In this way, using more capital and labor at the same time allows the firm to avoid (at least in part) the effects of diminishing marginal products.

The second benefit of being able to adjust capital in the long run is that producers often have some ability to substitute capital for labor or vice versa. Firms can be more flexible in their production methods and in the ways they respond to changes in the relative prices of capital and labor. For example, as airline ticket agents became relatively more expensive and technological progress made automated check-

The Long-Run Production Function

In a long- and choosing L (as we did for the short run), now the firm can choose the levels of both inputs.

and choosing L (as we did for the short run), now the firm can choose the levels of both inputs.

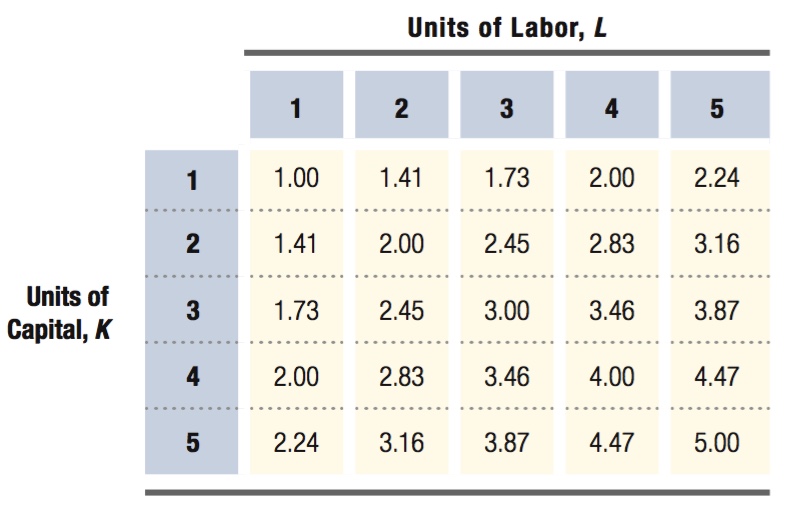

We can also illustrate the long-

In the fourth row of the table, where the firm has 4 units of capital, the values exactly match the short-

210