Supercharge Your Note Taking with a Four-Step Strategy

Note taking plays a key role in academic success.1 When you combine it with other important study skills and activities — reading, going to class, studying, taking exams, and writing and speaking — note taking helps you absorb, think about, remember, and use new information you’re learning in your courses. For instance, when you take notes in class or while reading an assigned textbook chapter, you can use those notes later to study for an exam or to deliver a presentation in class.

FOR DISCUSSION: Ask students what preconceptions they have about note taking. Some may feel that it’s not important or that they’ll never find a method that works. Encourage them to challenge these thoughts while they learn various techniques in this chapter. To normalize the concept, talk about how note taking has helped you personally.

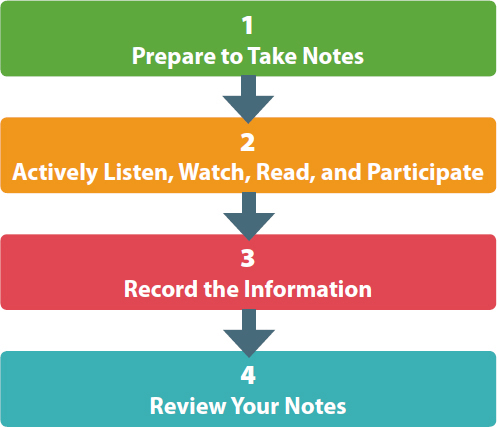

There is no “right” format for taking notes; you can choose from a variety of methods, depending on what works best for you. But no matter which method (or methods) you choose, you’ll get the most learning power from your notes if you approach note taking strategically. We recommend a four-step strategy: You start with preparation; you actively listen, watch, read, and participate; you record the information you’re learning; and you review your notes (see Figure 7.1).

Let’s take a closer look at each step.

FOR DISCUSSION: Depending on the class demographic, it may be beneficial to discuss the differences between note taking in high school and in college. Do students feel that strategies they used in high school will be helpful now? What changes have they needed to make to their note taking now that they’re in college?

Step 1: Prepare to Take Notes

When you prepare to take notes, you’ll find it much easier to focus on the most important information once you actually take notes — for instance, when you’re listening to a lecture, reading an assignment, or watching a video. Because preparation helps you focus, it boosts the quality and usefulness of your notes. Use these tactics to prepare successfully.

Gather the materials you’ll need to take notes. For example, find your textbook and the previous notes you took for that class or project. Decide ahead of time whether to handwrite your notes or type them on a laptop or tablet (see the Spotlight on Research). If you choose to write by hand, make sure to have a notebook, pens, and a highlighter handy. If you’re trying out a new note-taking app, which you can find with a quick Internet search, get comfortable with it before using it in class.

Create a system to label, organize, and store your notes. That way, you can easily find and review your notes later when you want to use them to study for an upcoming exam or to complete a homework assignment. The chapter on organization and time management contains ideas for creating a system for labeling, organizing, and storing your notes.

Preview key concepts. If you’re preparing to take notes during a lecture, review the course syllabus and complete any required reading before class. If you’re preparing to take notes while reading, use the previewing strategies described in the reading chapter, such as reviewing textbook chapter summaries, headings, and definitions to get a sense of the major ideas in the reading material.

Follow your schedule. If you’re attending lecture, arrive a few minutes early to review your notes from the previous class. If you plan to take notes while reading, follow your study schedule and begin work at the time you had planned.

Review your instructor’s PowerPoint slides and bring them to class. If an instructor provides slides in advance, you can start to familiarize yourself with the key concepts that will be covered in class. That way, you won’t have to write or type what’s already on the slides during lecture. Instead, you can focus on the instructor’s verbal explanation and take notes that expand on the information in the slides, either on the slide printout itself or in a separate document. In fact, taking your own notes instead of relying solely on your instructor’s slides has huge benefits: You think more about the information you’re learning, so you stand a better chance of understanding, remembering, and applying it.

Bring unanswered questions to class. If you have unresolved questions about your reading assignments, bring them to class. Your instructor may provide the information you’re looking for — or you can ask the questions in class to get the answers you need.

Stay positive. Remind yourself that note taking helps you maximize your learning.

FOR DISCUSSION: Ask students if they have unanswered questions about the reading they did in this chapter. Invite one or two students to share their questions, and discuss the answers as a class.

Step 2: Actively Listen, Watch, Read, and Participate

To take good notes, you’ll need to focus on the information you’re receiving, whether it comes to you during a lecture, from something you’re reading or discussing, or even from a video you watch for class. Focusing helps you identify the most important information in what you’re hearing or seeing so that you can capture it accurately for later review and use.

To sharpen your focus on the key information, engage with that information by actively listening, watching, reading, and participating (depending on the note-taking situation). These techniques can help.

Eliminate distractions. Even when you’re trying hard to pay attention, it can be tempting to grab your phone and text friends or reply to e-mails. When you give in to distractions, though, you miss chunks of information you’re supposed to absorb and record. So, take steps to eliminate distractions — for example, turn off your phone when you need to focus. The organization and time management chapter offers additional ideas for creating a distraction-free zone.

Empower yourself to concentrate. If you’re taking notes in class, sit in the front; you’ll find it easier to hear your instructor and participate in class discussion. Plus, when your instructor is looking you in the eye, you’ll be less likely to daydream, fiddle with your phone, or doze off. If you’re taking notes while reading, find a quiet location in which to work.

Look for written cues to important concepts in your reading. When you take notes while reading, look for section headings as well as boldfaced terms. These signal important concepts in the material. (See the reading chapter for more information.)

Listen for verbal cues from your instructors about what’s important. In class, instructors’ speech patterns can signal that certain information is especially crucial — for example, raising or lowering their voice when emphasizing points, or slowing down and repeating key concepts. Instructors might also use certain words and phrases alerting you to important material: “The main advantage …,” “Some of the challenges …,” “What we can conclude from this …,” “A key component …,” and (a student favorite) “People, this will be on the test.”

Watch for nonverbal cues. Pay attention to your instructors’ gestures and movements during class. Some instructors step out from behind the lectern, stop moving, point to a PowerPoint slide, or make direct eye contact when emphasizing an important point. We know of one instructor who rang a cowbell each time he introduced an important concept. (Most instructors are probably subtler than this!)

Participate in class. Get involved in what you’re learning in class. If your instructor encourages discussion, become an active participant: Contribute your thoughts about the topic of the day; ask questions about topics you’re curious about; and volunteer responses to your instructor’s questions. Participating in class can be intimidating — particularly if you’re uncomfortable speaking in front of others, the class is large, or you find the topic of discussion confusing — but give it your best shot. By participating actively, you can clarify confusing concepts, gain additional insights into what you’re learning, and stay focused on the material. And all of this helps you take better notes.

ACTIVITY: As a class, brainstorm ways that students can bring their focus back to coursework if they find their minds wandering. For example, they might lift their legs up off the chair and count to twenty. Create a top ten list from the suggestions.

FOR DISCUSSION: Connect the active listening concept with the world of work. Ask students: If you were in an important meeting with your boss, would you text, post on Instagram, or answer an e-mail? Probably not. You would give your boss your full attention. Students can start learning this transferable skill in the classroom.

ACTIVITY: Divide the class into groups. Ask students to write answers to the following: What are some verbal cues that you’ve heard in this class? In other classes? What are some nonverbal cues you’ve observed in this and other classes? Invite the groups to present their lists to the class.

CONNECT

TO MY EXPERIENCE

Think back to a time when you actively participated in class — for example, when you asked a great question, answered a question, or got your fellow classmates involved in a discussion. Briefly explain how it felt to contribute. Were you nervous? Excited? How do you plan to participate in your current classes?

WRITING PROMPT: Ask students to respond in writing to the following questions: How do you feel about participating in class? How can classroom participation, including raising your hand to ask a question, affect your learning? How does participation show that you are engaged? Why is it important to be engaged?

Step 3: Record Information

When it’s time to record information you hear or read, do it quickly, accurately, and in a way that makes sense to you. Later in the chapter, you’ll learn four specific methods for recording information, but these general strategies can also help.

Label your notes. At the top of the page, include a label with the course title, lecture topic, date, and a page number. If you handwrite your notes, use only one side of the page, and start notes for each lecture or reading assignment on a new piece of paper. If you type your notes, create a new document or move to a new page for each lecture or reading assignment.

Resist the urge to write down everything. Your instructors will talk faster than you can write, and not everything said in class or printed in a book is critical information. Instead, record only the main points and the most important details, using the active learning techniques you just read about.

Learn to paraphrase. Recording information verbatim (word-for-word) is important with chemical or mathematical formulas, definitions, dates, names, and diagrams because later you might need to reproduce these exactly on tests, in lab reports, or in papers. Often, though, it’s best to paraphrase information by restating it in your own words.2 For example, when you take notes as you read, if you just copy the words on the page into a notebook, you’re not interacting with the material. When you paraphrase, on the other hand, you have to think about what you’re reading, and then translate your understanding into your own words. Because you’re interacting with the information, you’re more likely to understand and remember it. Paraphrasing is also useful in class when you need to summarize the main points of a lecture or record key ideas from a PowerPoint slide. Table 7.1 shows an example of paraphrasing.

Use symbols and abbreviations to save time. You can create your own shorthand using symbols and abbreviations that work for you. For example, you might use an asterisk (*) to flag important information and the approximately symbol (≈) to indicate approximate numbers. (See Figure 7.3 and Figure 7.4 for more examples of useful symbols and abbreviations.)

Use metacognition to recognize when you don’t understand information. If you realize you have no idea what your instructor is saying or notice that you don’t understand a sentence you just read, you’re using metacognition. When you recognize that you’re confused, you have information you can act on: Write down your questions and get clarification as soon as you can. You might use a star, an exclamation point, or a question mark to indicate the confusing material or leave space to later jot down notes when you get answers to your questions. Taking action to clarify concepts will get you the answers you need — before you see the material on a test.

Ask questions. If your instructor allows questions during class (and most do!), raise your hand when you don’t understand material. Asking questions shows your instructor that you’re engaged in class and care about what you’re learning. If the instructor prefers to answer questions after class or during office hours, speak with him or her at the designated time and place.

If you have a disability, make use of accommodations. Depending on the type of disability you have, you may be able to audio- or video-record lectures or have another person take notes for you.

Paraphrase: To restate information in your own words.

ACTIVITY: Prepare a five-minute lecture on a class-appropriate topic, and ask students to paraphrase the information. Then, as a group, discuss what information the students wrote down. What main points of the lecture did they record?

Alternatively, divide the class into pairs. Give one member of each pair a short article on a subject of your choice, and after they’ve read the article, ask them to explain what they read, in their own words, to their partner. Write two or three questions about the article on the board. Then have the partners who heard the paraphrase answer the questions. How many questions did they answer correctly?

| Original content | Paraphrased content |

|---|---|

| “The first human beings to arrive in the Western Hemisphere emigrated from Asia. They brought with them hunting skills, weapon- and tool-making techniques, and other forms of human knowledge developed millennia earlier in Africa, Europe, and Asia. These first Americans hunted large mammals, such as the mammoths they had learned in Europe and Asia to kill, butcher, and process for food, clothing, and building materials. Most likely, these first Americans wandered into the Western Hemisphere more or less accidentally in pursuit of prey.” |

|

TAKING NOTES? GRAB A PEN AND PAPER

spotlight onresearch

With the popularity of laptops and tablets, more and more college students are coming to class with a computer. Typing notes is convenient, and often neater and faster than writing. But a question arises: When it comes to learning information for tests, is one method more effective than the other? Researchers Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer set out to investigate.

| Handwritten notes | Typed notes | |

|---|---|---|

| Recall test performance | + (Performed well) |

+ (Performed well) |

| Application test performance | + (Performed well) |

– (Performed less well) |

| Quantity of notes | – (Recorded less information) |

+ (Recorded more information) |

| Quality of notes | + (Took higher-quality notes) |

– (Took lower-quality notes) |

In the first of three studies, the researchers asked sixty-seven students to watch brief, recorded lectures and take notes using either a laptop or pad and paper. Students were asked to use their normal note-taking procedure from lecture classes — either typing or writing. After the note-taking activity, participants spent about thirty minutes doing other things and then were tested using two types of questions: fill-in-the-blank questions that required them to recall facts from the lecture, and essay questions that required them to apply the ideas from the lecture. Several interesting findings emerged.

Both groups performed equally well on the recall test (fill-in-the-blank questions).

Students who handwrote their notes did much better on the application test (essay questions).

Students who typed their notes recorded more information from the lecture — normally a good thing — but much of it was word-for-word. As you just read, paraphrasing is often the best way to learn and remember.

THE BOTTOM LINE

If possible, try writing your notes by hand. Doing so can help you apply the information you learn and take higher-quality notes than typing because you’re more likely to paraphrase than to record information word-for-word.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Question 7.1

1. Do you handwrite or type your notes? Why have you selected this method?

Question 7.2

2. If you type notes, do you record information word-for-word or put ideas into your own words?

Question 7.3

3. If you prefer to type your notes, will you try handwriting your notes now that you’ve learned about this study? Why or why not?

P. A. Mueller and D. M. Oppenheimer, “The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand over Laptop Note Taking,” Psychological Science 25 (2014): 1159–68.

Step 4: Review Your Notes

After you take notes, review them. Are they accurate? Complete? Do you have unanswered questions? If the information in your notes looks wrong or you don’t understand it, your notes won’t help you learn the material and use it to answer test questions or do class projects. Use these tips for reviewing your notes.

CONNECT

TO MY RESOURCES

Which of your friends or classmates are great note-takers? What systems are they using? Ask two of them to show you how they take notes. Write down three things you learn from them or ideas you’d like to try.

Review your notes when ideas are fresh in your mind. After you’ve taken notes, spend a few minutes skimming them to check that the information still makes sense. If you find things that are questionable, mark them so you know to come back and clarify them. Try to review your notes within a day to fill in missing information; otherwise, you might come back to the material a few days later and have no idea what your notes mean.

Compare your notes with other students’ notes. See whether you’re recording the same information and capturing the same level of detail as your classmates, and take the opportunity to clarify any concepts you found confusing.

Talk with your instructor. Visit your instructor during office hours, and ask for feedback on the quality of your notes. If you have questions or don’t fully grasp the material, ask for help.

Practice paraphrasing. If you wrote something down word-for-word in your notes, try paraphrasing this content. Paraphrasing will help you understand the ideas more fully.

Compare your notes to the study guide. If your instructor provides a study guide, compare your notes to the material it contains. Are the main ideas from your notes similar to those of the study guide? If not, add any missing content to your notes.

Clarify and reorganize your notes. If your handwritten notes are hard to read, type them out. If your typewritten notes are confusing, retype them in a clearer form in a new document. Reorganize the content of your notes to clarify the connections between ideas. If your notes are incomplete, fill in the gaps. According to research, meaningful time spent reviewing and rewriting your notes more clearly may help you get higher scores on exams.3

ACTIVITY: As a homework assignment, have students clarify and reorganize their notes. Later, students can use these reorganized notes as a study guide for future quizzes and exams.