10.3 Cross-Cultural Differences in Perception and Reasoning

Most studies of reasoning have been conducted in Western cultures, usually with university students as subjects. Thus, the studies may tell us more about how schooled Westerners think than about how human beings in general think. Researchers who have compared reasoning across cultures have found some interesting differences.

Responses of Unschooled Non-Westerners to Western-Style Logic Questions

Some psychologists have administered standard tests of reasoning, prepared originally for Westerners, to people in non-Western cultures. A general conclusion from such research is that the way people approach such tests—their understanding of what is expected of them—is culturally dependent. Non-Westerners, who haven’t attended Western-style schools, often find it absurd or presumptuous to respond to questions outside their realm of concrete experiences (Cole & Means, 1981; Scribner, 1977). Thus, the logic question, “If John is taller than Carl, and Carl is taller than Henry, is John taller than Henry?” is likely to elicit the polite response, “I’m sorry, but I have never met these men.” Yet the same person has no difficulty solving similar logic problems that present themselves in the course of everyday experience.

16

How do unschooled members of non-Western cultures typically perform on classification problems? Why might we conclude that differences in classification are based more on preference than on ability?

Researchers have also found that non-Westerners are more likely than Westerners to answer logic questions in practical, functional terms rather than in terms of abstract properties (Hamill, 1990). To solve classification problems, for example, Westerners generally consider it smarter to sort things by taxonomic category than by function, but people in other cultures do not. A taxonomic category, here, is a set of things that are similar in some property or characteristic, and a functional group is a set of things that are often found together, in the real world, because of their functional relationships to one another. For instance, consider this problem: Which of the following objects does not belong with the others: ax, log, shovel, saw? The correct answer, in the eyes of Western cognitive psychologists, is log because it is the only object that is not a tool. But when the Russian psychologist Alexander Luria (1971) presented this problem to unschooled Uzbekh peasants, they consistently chose shovel and explained their choice in functional terms: “Look, the saw and the ax, what could you do with them if you didn’t have a log? And the shovel? You just don’t need that here.” It would be hard to argue that such reasoning is any less valid than the reasoning a Westerner might give for putting all the tools together and throwing out the log.

389

Here are two other examples from one of Luria’s subjects, Rakmat, a 38-year-old illiterate peasant who was shown pictures of three adults and one boy (from Luria, 1976):

The examiner said, “Look, here you have three adults and one child. Now clearly the child doesn’t belong in this group.”

[Rakmat answered] “Oh, but the boy must stay with the others! All three of them are working, you see, and if they have to keep running out to fetch things, they’ll never get the job done, but the boy can do the running for them… The boy will learn; that’ll be better, then they’ll be able to work well together.” (p. 55)

Subject is then shown drawing of: bird-rifle-dagger-bullet.

[Rakmat answered] “The swallow doesn’t fit here…. No … this is a rifle. It’s loaded with a bullet and kills the swallow. Then you have to cut the bird up with the dagger, since there’s no other way to do it…. What I said about the swallow before is wrong! All these things go together.” (pp. 56–57)

This difference in reasoning may be one of preference more than of ability. Michael Cole and his colleagues (1971) described an attempt to test a group of Kpelle people in Nigeria for their ability to sort pictures of common objects into taxonomic groups. No matter what instructions they were given, the Kpelle persisted in sorting the pictures by function until, in frustration, the researchers asked them to sort them the way stupid people do. Then they sorted by taxonomy!

An East-West Difference: Focus on Wholes Versus Parts

Richard Nisbett and his colleagues have documented a number of differences in the perception and reasoning of people in East Asian cultures, particularly in Japan and China, compared to that of people in Western cultures, particularly in North America (Nisbett et al., 2001; Varnum et al., 2010). According to these researchers, East Asians perceive and reason more holistically and less analytically than do Westerners. In perceptual tests, East Asians tend to focus on and remember the whole scene and the interrelationships among its objects, whereas Westerners tend to focus on and remember the more prominent individual objects of the scene as separate entities, abstracted from their background.

17

How have researchers documented a general difference between Westerners and East Asians in perception and memory? How might this difference affect reasoning?

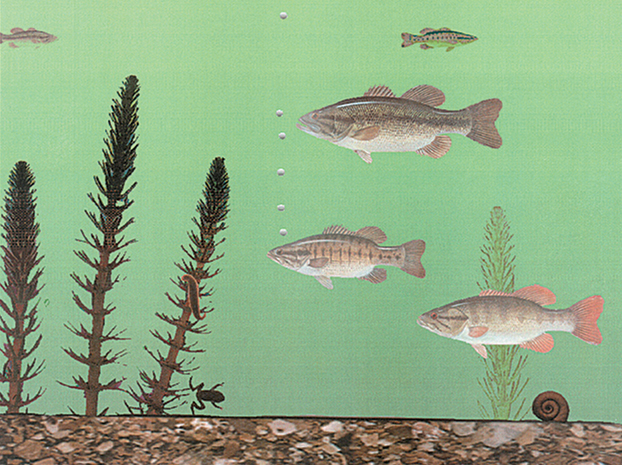

In one experiment, Japanese students at Kyoto University and American students at the University of Michigan viewed animated underwater scenes such as that depicted in Figure 10.6 (Masuda & Nisbett, 2001). Each scene included one or more large, active fish, which to the Western eye tended to dominate the scene, but also included many other objects. After each scene, the students were asked to describe fully what they had seen. The Japanese, on average, gave much more complete descriptions than did the Americans. Whereas the Americans often described just the large fish, the Japanese described also the smaller and less active creatures, the water plants, the flow of current, the bubbles rising, and other aspects of the scene.

390

The Japanese were also much more likely than the Americans to recall the relationships among various elements of the scene. For instance, they would speak of the large fish as swimming against the water’s current, or of the frog as swimming underneath one of the water plants. Subsequently, the students were shown pictures of large fish and were asked to identify which ones they had seen in the animated scenes. Some of the fish were depicted against the same background that had existed in the original scene, and some were depicted against novel backgrounds. The Japanese were better at recognizing the fish when the background was the same as the original than when it was different, whereas the Americans’ ability to recognize them was unaffected by the background. Apparently the Japanese had encoded the fish as integrated parts of the whole scene, while the Americans had encoded them as entities distinct from their background.

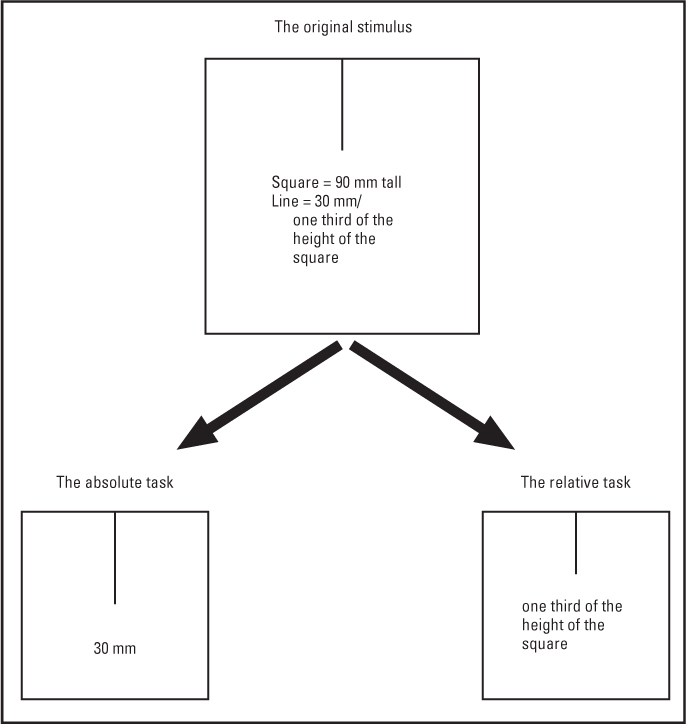

In other research Japanese and American adults were shown a box with a line drawn in it (see Figure 10.7), and, in a smaller box, had to reproduce either the absolute length of the line (bottom left) or the relative length of the line (bottom right) (Kitayama et al., 2003). As you might expect, the American subjects were more accurate in performing the absolute task, reflective of analytic processing, whereas the Japanese subjects were more accurate in performing the relative tasks, reflective of holistic processing. This cross-national pattern is found as early as 6 years of age (Duffy et al., 2009; Vasilyeva et al., 2007). However, both American and Japanese 4-and 5-year-old children find the absolute task more difficult (Duffy et al., 2009), suggesting that children over the world begin life with a more “relational/holistic” bias. But, depending on cultural practices, some time around 6 years of age, American children become socialized to focus their attention, whereas Japanese children become socialized to divide their attention.

East Asians’ attention to background, context, and interrelationships apparently helps them to reason differently in some ways from the way Westerners do (Nisbett & Masuda, 2007; Nisbett et al., 2001). For instance, when asked to describe why an animal or a person behaved in a certain way, East Asians more often than Americans talk about contextual forces that provoked or enabled the behavior. Americans, in contrast, more often talk about internal attributes of the behaving individual, such as motivation or personality. Thus, in explaining a person’s success in life, East Asians might talk about the supportive family, the excellent education, the inherited wealth, or other fortunate circumstances that made such success possible, while Americans are relatively more likely to talk about the person’s brilliant mind or capacity for hard work.

Nobody knows for sure why these differences in perception and reasoning between Westerners and East Asians came about. The difference certainly is not the result of genetic differences. The offspring of East Asians who have emigrated to North America begin to perceive and think more like other Americans than like East Asians within a generation or two (Nisbett et al., 2001). Nisbett and his colleagues suggest that the roots of the difference are in ancient philosophies that underlie the two cultures. Western ways of thinking have been much influenced, historically, by ancient Greek philosophy, which emphasizes the separate, independent nature of individual entities, including individual people. East Asian ways of thinking have been much influenced by ancient Asian philosophies, such as Confucianism, which emphasize the balance, harmony, and wholeness of nature and of human society.

391

SECTION REVIEW

There are cultural differences in perception and reasoning.

- Non-Westerners who lack formal schooling apply rules of logic that are more closely tied to everyday, practical function than to abstract concepts.

- East Asian subjects tend to focus on the entire context of a problem or situation, as do very young children in both Western and East Asian cultures.