12.5 Adolescence: Breaking Out of the Cocoon

Adolescence is the transition period from childhood to adulthood. It begins with the first signs of puberty (the physical changes leading to reproductive capacity, discussed in Chapter 11), and it ends when the person is viewed by him- or herself, and by others, as a full member of the adult community. Defined this way, adolescence in our culture begins earlier and ends later than it did in times past or still does in many other cultures.

Acceptance by self and others into adulthood—the end of adolescence—comes gradually in our culture and has no clear-cut markers. In traditional societies, where adult roles are clearly defined and are learned through the child’s direct involvement in the adult world, the transition to adulthood may coincide with one or another of the physical changes near the end of puberty and be officially marked by rites of passage or other celebrations. But our culture lacks such rites, and our laws dole out adult privileges and responsibilities inconsistently over a wide age span. In most states of the United States, young people are first allowed to drive a car at 16, enlist in the military at 17, vote at 18, and purchase alcohol at 21. Although the average age for first marriage is currently about 29 for men and 27 for women in the United States (and many other industrialized countries), the legal age for marriage varies from 13 to 21, depending on state of residence, sex, and whether parental permission has been granted. More important, the age at which people actually begin careers or families, often seen as marks of entry into adulthood, varies greatly. If you prefer to define adolescence as the teenage years, as many people do, you can think of this section as about adolescence and youth, with youth defined as a variable period after about age 20 that precedes one’s settling into routines of career or family.

In Erikson’s life-span theory, adolescence is the stage of identity crisis, the goal of which is to give up one’s childhood identity and establish a new identity—including a sense of purpose, a career orientation, and a set of values—appropriate for entry into adulthood (Erikson, 1968). Many developmental psychologists today disagree with Erikson’s specific definition of identity and with his idea that the search for identity necessarily involves a “crisis,” but nearly all agree that adolescence is a period in which young people either consciously or unconsciously act in ways designed to move themselves from childhood toward adulthood. With an eye on how they affect adolescents’ emerging self-identities, we shall look here at adolescents’ breaking away from parents, forming closer relationships with peers, risk taking, delinquency, bravery, morality, and sexual explorations.

484

Shifting from Parents to Peers for Intimacy and Guidance

A big part of growing up is becoming independent, and this typically involves breaking away from parental control and becoming more involved with peers and “peer life.” This often results in conflict between adolescents and their parents, as adolescents simultaneously form closer bonds with peers.

Breaking Away from Parental Control

“I said, ‘Have a nice day,’ to my teenage daughter as she left the house, and she responded, ‘Will you please stop telling me what to do!’” That joke, long popular among parents of adolescents, could be matched by the following story, told by an adolescent: “Yesterday, I tried to really communicate with my mother. I told her how important it is that she trust me and not try to govern everything I do. She responded, ‘Oh, sweetie, I’m so glad we have the kind of relationship in which you can be honest and tell me how you really feel. Now, please, if you are going out, wear your warmest coat and be back by 10:30.’”

25

What is the typical nature of the so-called adolescent rebellion against parents?

Adolescence is often characterized as a time of rebellion against parents, but it rarely involves out-and-out rejection. Surveys taken at various times and places over the past several decades have shown that most adolescents admire their parents, accept their parents’ religious and political convictions, and claim to be more or less at peace with them (Offer & Schonert-Reichl, 1992; Steinberg, 2001). The typical rebellion, if one occurs at all, is aimed specifically at some of the immediate controls that parents hold over the child’s behavior. At the same time that adolescents are asking to be treated more like adults, parents may fear new dangers that can accompany this period of life—such as those associated with sex, alcohol, drugs, and automobiles—and try to tighten controls instead of loosening them. So adolescence is often marked by conflicts centering on parental authority.

For both sons and daughters, increased conflict with parents is linked more closely to the physical changes of puberty than to chronological age (Steinberg, 1989). If puberty comes earlier or later than is typical, so does the increase in conflict. Such conflict is usually more intense in the early teenage years than later (Steinberg, 2001); by age 16 or so, most teenagers have achieved the balance of independence and dependence they are seeking.

Establishing Closer Relationships with Peers

As adolescents gain more independence from their parents, they look increasingly to their peers for emotional support. In one study, for example, fourth graders indicated that their parents were their most frequent providers of emotional support, seventh graders indicated that they received almost equal support from their parents and friends, and tenth graders indicated that they received most of their emotional support from friends (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992).

Conforming to Peers

26

What evidence suggests that peer pressure can have negative and positive effects? What difference in attitude about peer pressure is reported to exist in China compared to the United States?

As children approach and enter their teenage years, they become increasingly concerned about looking and behaving like their peers. Self-report measures indicate that young people’s tendency to conform peaks in the years from about age 10 to 14 and then declines gradually after that (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). The early teenage years are, quite understandably, the years when parents worry most about possible negative effects of peer pressure. Indeed, teenagers who belong to the same friendship groups are more similar to one another with regard to such risky behaviors as smoking, drinking, drug use, and sexual promiscuity than are teenagers who belong to different groups (Steinberg, 2008a). Such similarity is at least partly the result of selection rather than conformity; people tend to choose friends who have interests and behaviors similar to their own. Still, a number of research studies have shown that, over time, friends become more similar to one another in frequency of risky or unhealthful behaviors than they were originally (Curran et al., 1997; Jaccard et al., 2005).

485

Western parents and researchers tend to emphasize the negative influences of peers, but adolescents themselves often describe positive peer pressures, such as encouragement to avoid unhealthful behaviors and engage in healthful ones (Steinberg, 2008a). On the basis of extensive studies in China, Xinyin Chen and his colleagues (2003) report that Chinese parents, educators, and adolescents view peer pressure much more as a positive force than as a negative one. In China, according to Chen, young people as well as adults place high value on academic achievement, and adolescent peer groups do homework together and encourage one another to excel in school. In the United States, in contrast, peer encouragement for academic achievement is relatively rare (Steinberg, 1996).

Increased Rates of Recklessness and Delinquency

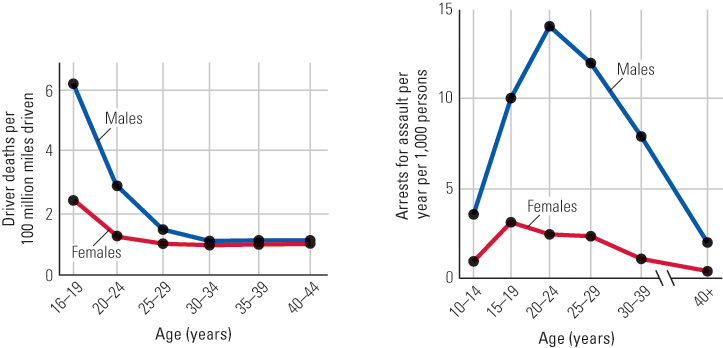

On a statistical basis, throughout the world, people are much more likely to engage in disruptive or dangerous actions during adolescence than at other times in life. In Western cultures, rates of theft, assault, murder, reckless driving, unprotected sex, illicit drug use, and general disturbing of the peace all peak between the ages of 15 and 25 (Archer, 2004; Arnett, 1995, 2000). The adolescent peak in recklessness and delinquency is particularly sharp in males, as exemplified in the graphs in Figure 12.6.

What causes the increased recklessness and delinquency? Some psychologists have tried to address this question by attempting to discern the underlying cognitive, motivational, or brain characteristics of adolescents that differentiate them from adults. Adolescents have been described as having a myth of invulnerability—that is, a false sense that they are protected from the mishaps and diseases that can happen to other people (Elkind, 1978). They have also been described as sensation seekers, who enjoy the adrenaline rush associated with risky behavior; as having heightened irritability or aggressiveness, which leads them to be easily provoked; and as having immature inhibitory control centers in the prefrontal lobes of their brains (Arnett, 1992, 1995; Bradley & Wildman, 2002; Martin et al., 2004; Steinberg, 2008b). Reasonable evidence has been compiled for all of these ideas, but such concepts leave one wondering why adolescents have such seemingly maladaptive characteristics, which can lead to their deaths. Why would natural selection not have weeded out such traits?

486

Explanations That Focus on Adolescents’ Segregation from Adults

27

What are two theories about how adolescents’ segregation from adults might contribute to their recklessness and delinquency?

One line of explanation focuses on aspects of adolescence that are relatively unique to modern, Western cultures. In this view, adolescent recklessness is largely an aberration of modern times, not a product of natural selection. Terrie Moffitt (1993), for example, suggests that the high rate of delinquency is a pathological side effect of the early onset of puberty and delayed acceptance into legitimate adult society. She cites evidence that the adolescent peak in violence and crime is greater in modern cultures than in traditional cultures, where puberty usually comes later and young people are more fully integrated into adult activities. According to Moffitt, young people past puberty, who are biologically adults, are motivated to enter the adult world in whatever ways are available to them. Sex, alcohol, and crime are understood as adult activities. Crime, in particular, is taken seriously by adults and brings adolescents into the adult world of lawyers, courtrooms, and probation officers. Crime can also bring money and material goods that confer adult-like status.

Moffitt’s theory makes considerable sense, but it does not account well for risky adolescent activities that are decidedly not adult-like. Adults do not “surf” on the tops of fast-moving trains or drive around wildly in stolen cars and deliberately crash them, as adolescents in various cities have been observed to do (Arnett, 1995).

In a theory that is in some ways the opposite of Moffitt’s, Judith Harris (1995, 1998) suggests that adolescents engage in risky and delinquent activities not to join the adult world but to set themselves apart from it. Just as they dress differently from adults, they also act differently. According to Harris, their concern is not with acceptance by adults but with acceptance by their own peers—the next generation of adults. Harris agrees with Moffitt that our culture’s segregation of adolescents from adult society contributes to adolescents’ risky and sometimes delinquent behavior, but she disagrees about the mechanism. To Moffitt, such segregation reduces the chance that adolescents can find safe, legitimate ways to behave as adults; to Harris it does so by producing adolescent subcultures whose values are relatively unaffected by those of adults. Moffitt’s and Harris’s theories may each contain part of the truth. Perhaps adolescents seek adult-like status while, at the same time, identifying with the behaviors and values of their adolescent subculture.

The Neurological Basis of Risk-Taking in Adolescence

Although the psychological reasons for adolescents’ high levels of risk-taking behavior are debatable, such behavior is surely governed by underlying changes in adolescents’ brains. Lawrence Steinberg (2007, 2008b) has proposed that adolescent risk taking reflects a competition between two developing brain systems, the cognitive-control network, involved in planning and regulating behavior and located primarily in the frontal lobes, and the socioemotional network, located primarily in the limbic system (see Chapter 5). According to Steinberg, although adolescents are able to make logical decisions as well as young adults under “neutral” conditions, the socioemotional brain network becomes dominant under conditions of emotional or social arousal or when in the presence of peers. The result is that, although adolescents may “know better” than to engage in some forms of risky behavior, the presence of peers interferes with their cognitive-control network, increasing the incidence of risky behaviors in social settings.

487

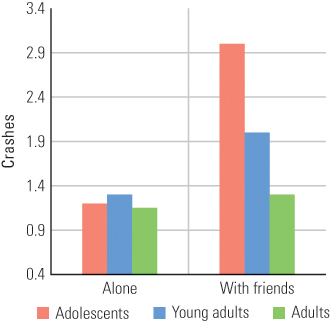

The impact of peers on risky behavior in adolescents is demonstrated in research using a simulated driving task (Gardner & Steinberg, 2004). Adolescents (13 to 16 years old), young adults (average age = 19 years), and adults (average age = 37 years) were equally able to avoid “crashes” during the video simulations when driving alone, but the pattern was substantially different when driving in the presence of friends (See Figure 12.7). As you can see in the figure, the number of crashes was about the same for the adults whether they were alone or with friends. In contrast, the number of crashes was substantially greater for adolescents, and moderately greater for young adults, in the social situation. In a subsequent brain imaging experiment, where adolescents performed the driving task either with or without a peer watching them, reward-related areas of the brain were more active when peers were watching them then when they were not. There was no difference in the activation of the cognitive control areas between the two conditions (Chein et al., 2011). The results of these laboratory simulations are similar to actual driving statistics. The rate of vehicular deaths for 16- and 17-year-old drivers more than doubles when there are three or more passengers in the car compared to when adolescents drive alone. In contrast, there is no relationship between vehicular deaths and the number of passengers for older drivers (Chen et al., 2000).

An Evolutionary Explanation of the “Young-Male Syndrome”

Neither Moffitt nor Harris addresses the question of why risky and delinquent activities are so much more readily pursued by young males than by young females or why they occur, at least to some degree, in cultures that do not segregate adolescents from adults. Even in hunter-gatherer communities, young males take risks that appear foolish to their elders; they also die at disproportionate rates from such mishaps as falling from trees that they have climbed too rapidly (Hewlett, 1988). To address such issues, Margo Wilson and Martin Daly (1985; Daly & Wilson, 1990) have discussed what they call “the young-male syndrome” from an evolutionary perspective, focusing on the potential value of such behavior for reproduction.

28

How have Wilson and Daly explained the recklessness and delinquency of adolescent males in evolutionary terms?

As discussed in Chapter 3, among mammals in general, the number of potential offspring a male can produce is more variable than the number a female can produce and is more closely tied to status. In our species’ history, males who took risks to achieve higher status among their peers may well have produced more offspring, on average, than those who didn’t, so genes promoting that tendency may have been passed along. This view gains credibility from studies in which young women report that they indeed are sexually attracted to men who succeed in risky, adventurous actions, even if such actions serve no social good (Kelly & Dunbar, 2001; Kruger et al., 2003). In hunter-gatherer times, willingness to take personal risks in hunting and defense of the tribe and family may well have been an especially valuable male trait. According to Wilson and Daly, train surfing, wild driving, careless tree climbing, and seemingly senseless acts of violence are best understood as ways in which young men gain status by demonstrating their fearlessness and valor.

In support of their thesis, Wilson and Daly point to evidence that a high proportion of violence among young men is triggered by signs of disrespect or challenges to status. One young man insults another, and the other responds by punching, knifing, or shooting him. Such actions are more likely to occur if other young men are present than if they aren’t. No intelligent person whose primary goal was murder would choose to kill in front of witnesses, but young men who commit murder commonly do so in front of witnesses.

488

Of course, not all young males are reckless or violent, but that does not contradict Wilson and Daly’s thesis. Those who see safer paths to high status—such as through college, inherited wealth, or prestigious jobs—have less need to risk their lives for prestige and are less likely to do so.

Females also exhibit a peak in violence during adolescence and youth, although it is a much smaller peak than men’s (refer back to Figure 12.6). Anne Campbell (1995, 2002) has argued that when young women do fight physically, they do so for reasons that, like the reasons for young men’s fighting, can be understood from an evolutionary perspective. According to Campbell’s evidence, young women fight most often in response to gossip or insults about their alleged sexual activities, which could tarnish their standing with men, and in instances when one woman appears to be trying to attract another’s boyfriend.

An Expanded Moral Vision and Moral Sense of Self

Adolescence seems to bring out both the worst and the best in people. Adolescents can be foolhardy and violent, but they can also be heroic and work valiantly toward making the world better. Adolescence is, among other things, a period of rapid growth in the sophistication of moral reasoning and a time in which many people develop moral self-images that guide their actions.

Advancement on Kohlberg’s Scale of Moral Reasoning

29

How did Kohlberg assess moral reasoning? How can his stages be described as the successive broadening of one’s social perspective? How does research using Kohlberg’s system help explain adolescent idealism?

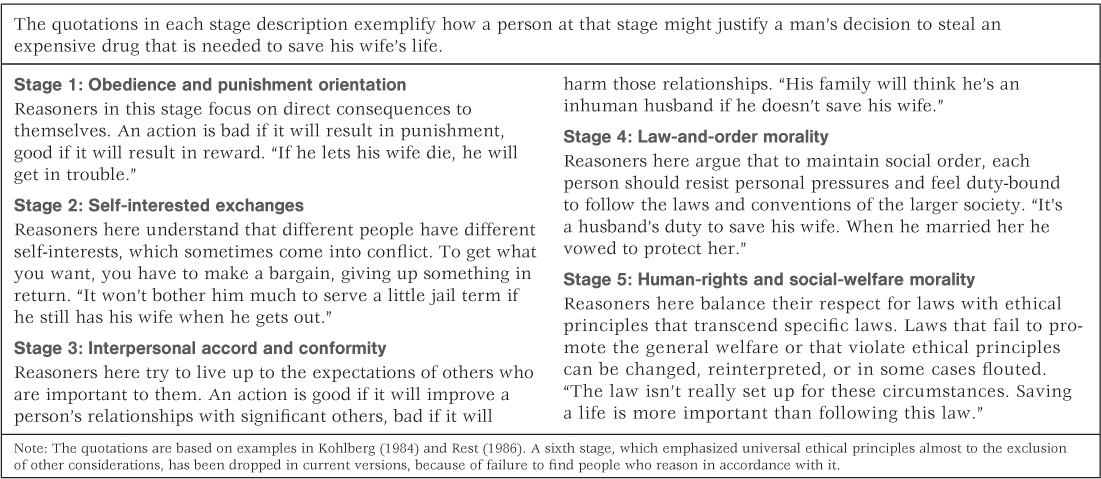

Over the past 45 years or so, most research on moral development has been based on a theory and methods developed originally by Lawrence Kohlberg. Kohlberg assessed moral reasoning by posing hypothetical dilemmas to people—primarily to adolescents—and asking them how they believed the protagonist should act and why. In one dilemma, for example, a man must decide whether or not to steal a certain drug under conditions in which that theft is the only way to save his wife’s life. To evaluate the level of moral reasoning, Kohlberg was concerned not with whether people answered yes or no to such dilemmas but with the reasons they gave to justify their answers. Drawing partly on his research findings and partly on concepts gleaned from the writings of moral philosophers, Kohlberg (1984) proposed that moral reasoning develops through a series of stages, which are outlined in Table 12.3.

Kohlberg’s stages of moral reasoning

489

As you study Table 12.3, notice the logic underlying Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning. Each successive stage takes into account a broader portion of the social world than does the previous one. The sequence begins with thought of oneself alone (Stage 1) and then progresses to encompass other individuals directly involved in the action (Stage 2), others who will hear about and evaluate the action (Stage 3), society at large (Stage 4), and, finally, universal principles that concern all of humankind (Stage 5).

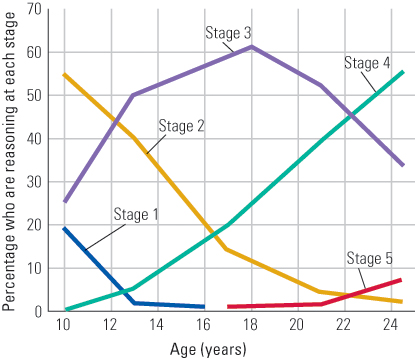

According to Kohlberg, the stages represent a true developmental progression in the sense that, to reach any given stage, a person must first pass through the preceding ones. Thinking within one stage and discovering the limitations of that way of thinking provide the impetus for progression to the next. Kohlberg did not claim that everyone goes through the entire sequence; in fact, his research suggested that few people go beyond Stage 4, and many stop at Stage 2 or Stage 3. Nor did he link his stages to specific ages, but he did contend that adolescence and young adulthood are the times when advancement to the higher stages is most likely to occur. Figure 12.8 illustrates the results of one long-term study that supports Kohlberg’s claim about the rapid advancement of moral reasoning during adolescence.

Kohlberg’s theory is about moral reasoning, which is not the same thing as moral action. Kohlberg recognized that one can be a high-powered moral philosopher without being a moral person, and vice versa, yet he argued that the ability to think abstractly about moral issues does help account for the idealism and moral commitment of youth. In line with this contention, several research studies found that adolescents who exhibited the highest levels of moral reasoning were also the most likely to help others, to volunteer to work for social causes, or to refrain from taking part in actions that harm other people (Haan et al., 1968; Kuther & Higgins-D’Alessandro, 2000; Muhlberger, 2000).

Sexual Explorations

Adolescence is first and foremost the time of sexual blooming. Pubertal hormones act on the body to make it reproductively functional (discussed in Chapter 11) and on the brain to heighten greatly the level of sexual desire (discussed in Chapter 6). Girls and boys who previously watched and teased each other from the safety of their same-sex groups become motivated to move closer together, to get to know each other, to touch in ways that aren’t just teasing. The new thoughts and actions associated with all these changes can bring on fear, exhilaration, dread, pride, shame, and bewilderment—sometimes all at once.

In their early dating, teenagers who have grown more or less separately in the “world of boys” and the “world of girls” come together and learn how to communicate with one another. For boys it may be a matter of learning how to pay closer attention to another’s needs and to speak in a more accommodating, less assertive manner. For girls it may often be a matter of learning to be more assertive. One study found that 10th graders’ discussions with their romantic partner were more difficult than their discussions either with a close same-sex friend or with their own mother (Furman & Shomaker, 2008). More negativity was expressed, and there was more failure in communication. Yet, when asked, teenagers commonly regard their romantic relationship as their closest relationship and their most important source of emotional support (Collins et al., 2009). Longitudinal studies indicate, not surprisingly, that success in developing emotional intimacy in early romantic relationships is highly predictive of eventual success in marriage (Karney et al., 2007).

490

The Development of Sexuality and Sexual Behavior in Adolescence

As a culture, we glorify sex and present highly sexual images of teenagers in advertisements and movies; yet, at the same time, we typically disapprove of sex among the real teenagers of everyday life. Teenage sex is associated in the public mind with delinquency, and, indeed, the youngest teenagers to have sexual intercourse are often those most involved in delinquent or antisocial activities (Capaldi et al., 1996). Earliest intercourse usually occurs surreptitiously, often without benefit of adult advice, and often without a condom or other protection against pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

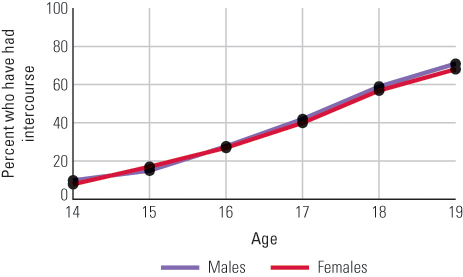

Sexual Attraction Sexual behavior follows a typical pattern for adolescents in developed countries. Adults recall their earliest feelings of sexual attraction occurring between 10 and 12 years of age, although this varies with sex, culture, and sexual orientation (Herdt & McClintock, 2000). This is typically followed about a year later by first sexual fantasies, which are actually adolescents’ most common sexual experience, and by the beginning of masturbation (Collins & Steinberg, 2006; DeLamater & Friedrich, 2002; Feldman et al., 1999). Many adolescents move on to sexual behavior with a partner, typically beginning with “making out” and “petting” and, for many, sexual intercourse. Figure 12.9 shows the percentage of American males and females who reported having had sexual intercourse between the ages of 14 and 19 years. As you can see, although few young teenagers report having sex, this increases to about 70 percent by age 19 (Guttmacher Institute, 2006).

Sexual-Minority Development For those whose sexual orientation is not the culture’s ideal, the sexual awakening of adolescence can be especially difficult. The developmental process of sexual identity for gay and lesbian (sexual-minority) youth is similar to that for heterosexual youth. Many children become aware of same-sex attraction when they are approximately 8 to 10 years olds (Savin-Williams, 1998), years before most children display mature sexual feelings or behaviors, although for others, such awareness is not attained until adolescence. In fact, it is not uncommon for women’s first awareness of being a lesbian or bisexual to occur until after years of maintaining heterosexual relationships and even motherhood (D’Augelli & Patterson, 2001).

The average age that people identify themselves as a sexual minority is about 15, although, again, this is highly variable (Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2004). Girls are likely to have labeled themselves as lesbian or bisexual before engaging in homosexual acts, whereas boys often to not label themselves as gay until after they have had sex with another boy (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). It is typically several more years, usually between 17 and 19 years of age, before sexual-minority youth “go public,” first telling their siblings and close friends of their sexual orientation, and later their parents (usually their mothers rather than their fathers). “Coming out” can often lead to loss of some heterosexual friends, disappointment from one’s parents, and physical and verbal abuse from peers, especially in some ethnic groups (more so in Latin and Asian American than European American groups) and in some conservative religions (D’Augelli, 2005). It is not surprising, then, that some youth choose to hide their sexual identify from friends and family.

As a result of the discrimination and abuse that some sexual-minority youth experience, they often show poorer psychological adjustment (for example, school problems, substance abuse) than their heterosexual peers. However, when youth truly accept their sexual identity and receive the support of family and friends (which does not always happen), psychological adjustment is apt to be good (D’Augelli, 2004) despite the cultural stigmatization that continues to exist in certain segments of some societies.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Pregnancy Not surprising, sexual intercourse can sometimes lead to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and pregnancy. The rates of STDs in American teenagers and young adults are exceptionally high. Although 15- to- 24-year-olds represent only about a quarter of sexually experienced people in the United States, they account for nearly half of the new cases of STDs (Centers for Disease Control, 2010). Based on a 2008 report by the Centers for Disease Control, approximately 3.2 million girls between the ages of 14 and 19–26 percent of that population—were infected with at least one of the most common STDs. The rate of infection increased to 40 percent for sexually active girls (Forhan et al., 2008).

491

Concerning pregnancy, in the United States in recent times, roughly 7 percent of teenage females aged 15 to 19 became pregnant in any given year (Kost & Henshaw, 2013). About a quarter of these pregnancies were terminated by abortion, and most of the rest resulted in births. Most teenage pregnancies occurred outside of marriage, often to mothers who were not in a position to care for their babies adequately. The good news is that the rate of teenage pregnancy has fallen, from a peak of about 12 percent reached in 1990, and it may be declining further still. The decline apparently stems primarily from a sharp increase in teenagers’ use of condoms and other birth control methods, which itself appears to be a result of increased sex education in schools and parents’ greater willingness to discuss sex openly with their children and teenagers (Abma et al., 2004).

30

What correlations have been observed between sex education and rates of teenage pregnancy?

The United States, however, still lags behind the rest of the industrialized world in sex education and in use of birth control by teenagers, and still has the highest teenage pregnancy rate of any industrialized nation. Such countries as Germany, France, and the Netherlands have teenage pregnancy rates that are less than one-fourth the rate in the United States (Abma et al., 2004; Guttmacher Institute, 2002), despite the fact that their rates of teenage sexual activity are equivalent to that in the United States.

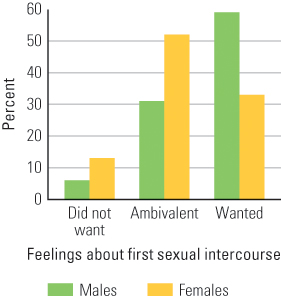

A long-standing problem arises from the persistent double standard regarding sexuality for girls and boys, which probably stems from biological as well as cultural influences. Not just in Western culture, but in most cultures worldwide, boys are more often encouraged in their sexual adventures, and are more likely to feel proud of them, than are girls (Gordon & Gilgun, 1987; Michael et al., 1994). Boys, more often than girls, say that they are eager to have sex for the sheer pleasure of it, and girls, more often than boys, equate sex with love or say that they would have intercourse only with someone they would marry. One index of this difference is depicted in Figure 12.10, which shows results of a survey conducted in the United States in 2002 (Abma et al., 2004). Far more young women than young men reported that they did not want their first sexual intercourse to happen at the time that it did happen. A separate analysis showed that the younger a teenage female was when she had her first intercourse, the less likely she was to have wanted it to happen.

Evolutionary Explanation of Sex Differences in Sexual Eagerness

31

How can the sex difference in desire for uncommitted sex be explained in evolutionary terms?

In culture after culture, young men are more eager than young women to have sexual intercourse without a long-term commitment (Buss, 1994, 1995; Schmitt, 2003). Why? The standard evolutionary explanation is founded on the theory of parental investment, developed by Robert Trivers (1972) to account for sex differences in courtship and mating in all animal species. According to the theory (discussed more fully in Chapter 3), the sex that pays the greater cost in bearing and rearing young will—in any species—be the more discriminating sex in choosing when and with whom to copulate, and the sex that pays the lesser cost will be the more aggressive in seeking copulation with multiple partners.

The theory can be applied to humans in a straightforward way. Sexual intercourse can cause pregnancy in women but not in men, so a woman’s interest frequently lies in reserving intercourse until she can afford to be pregnant and has found a mate who will help her and their potential offspring over the long haul. In contrast, a man loses little and may gain much—in the amoral economics of natural selection—through uncommitted sexual intercourse with many women. Some of those women may succeed in raising his children, sending copies of his genes into the next generation, at great cost to themselves and no cost to him. Thus natural selection may well have produced an instinctive tendency for women to be more sexually restrained than men.

492

How Teenage Sexuality May Depend on Conditions of Rearing

32

How can sexual restraint and promiscuity, in both sexes, be explained as adaptations to different life conditions? What evidence suggests that the presence or absence of a father at home, during childhood, may tip the balance toward one strategy or the other?

A key word in the last sentence of the preceding paragraph is tendency. Great variation on the dimension of sexual restraint versus promiscuity exists within each sex, both across cultures and within any given culture (Belsky et al., 1991; Small, 1993). As in any game of strategy, the most effective approach that either men or women can take in courtship and sex depends very much on the strategy taken by the other sex. In communities where women successfully avoid and shun men who seek to behave promiscuously, promiscuity proves fruitless for men and the alternative strategy of fidelity works best. Conversely, in communities where men rarely stay around to help raise their offspring, a woman who waits for “Mr. Right” may wait forever. Cross-cultural studies have shown that promiscuity prevails among both men and women in cultures where men devote little care to young, and sexual restraint prevails in cultures where men devote much care (Barber, 2003; Draper & Harpending, 1988; Marlowe, 2003).

Some researchers have theorized that natural selection may have predisposed humans to be sensitive to cues in childhood that predict whether one or the other sexual strategy will be more successful. One such cue may be the presence or absence of a caring father at home. According to a theory originated by Patricia Draper and Henry Harpending (1982), the presence of a caring father leads girls to grow up assuming that men are potentially trustworthy providers and leads boys to grow up assuming that they themselves will be such providers; these beliefs promote sexual restraint and the seeking of long-term commitments in both sexes. If a caring father is not present, according to the theory, girls grow up assuming that men are untrustworthy “cads” rather than “dads,” and that assumption leads them to flaunt their sexuality to extract what they can from men in short-term relationships. For their part, boys who grow up without a caring father tend to assume that long-term commitments to mates and care of children are not their responsibilities, and that assumption leads them to go from one sexual conquest to another. These assumptions may not be verbally expressed or even conscious, but are revealed in behavior.

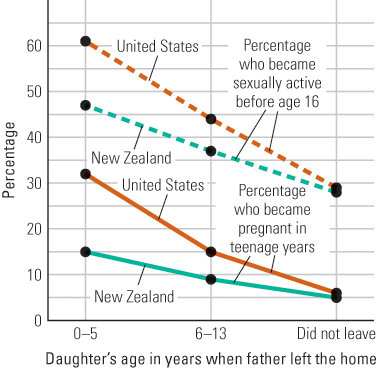

In support of their theory, Draper and Harpending (1982, 1988) presented evidence that even within a given culture and social class, adolescents raised by a mother alone are generally more promiscuous than those raised by a mother and father together. In one early study, teenage girls who were members of the same community playground group and were similar to one another in socioeconomic class were observed for their degrees of flirtatiousness, both with boys on the playground and with an adult male interviewer. Girls who were raised by a mother alone—after divorce early in the girl’s childhood—were, on average, much more flirtatious than girls who still had a father at home (Hetherington, 1972). Other, more recent studies have revealed that girls raised by a mother alone are much more likely to become sexually active in their early teenage years and to become pregnant as teenagers than are girls raised by a mother and father (Ellis, 2004; Ellis et al., 2003). The results of two studies, conducted in the United States and New Zealand, are depicted in Figure 12.11 (Ellis et al., 2003).

493

Researchers have also found that girls raised in father-absent homes tend to go through puberty earlier than do those raised in homes where a father is present (Belsky, 2007; Ellis, 2004). This difference has even been shown within families, in a study comparing the age of menarche for full sisters (Tither & Ellis, 2008). In cases where the father left the family, the younger sisters—the ones who were still young children when the father left—reached menarche at an earlier age than did the older sisters. Since the sisters in each pair had the same mother and father, this consistent difference must have been the result of a difference in experience, not a difference in genes. Early puberty may be part of the mechanism through which experiences at home affect the onset of sexual activity.

Draper and Harpending’s theory is still controversial, though an increasing amount of evidence supports it (Belsky, 2007; Ellis et al., 2012). Regardless of whether or not the theory eventually proves to be true, it illustrates the attempt of many contemporary psychologists to understand the life course in terms of alternative strategies that are at least partly prepared by evolution but are brought selectively to the fore by life experience.

SECTION REVIEW

Adolescence is a period of breaking away and developing an adult identity.

Shifting from Parents to Peers

- Adolescent conflict with parents generally centers on the desire for greater independence from parental control.

- Increasingly, adolescents turn to one another rather than to their parents for emotional support.

- Peer pressure can have positive as well as negative influences.

Recklessness and Delinquency

- Risky and delinquent behaviors are more frequent in adolescence than in other life stages.

- Segregation from adults may promote delinquency by depriving adolescents of positive adult ways to behave, or by creating an adolescent subculture divorced from adult values.

- Risky and delinquent behavior is especially common in young males. It may serve to enhance status, ultimately as part of competition to attract females.

The Moral Self

- In Kohlberg’s theory, moral reasoning develops in stages, progressing in breadth of social perspective. Rapid advancement in moral reasoning often occurs in adolescence.

Sexual Explorations

- Sexual attraction, to members of the opposite sex or to same-sex peers, develops gradually over adolescence, with feelings of sexual attraction usually beginning between 10 and 12 years of age.

- Rates of sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy in American teenagers and young adults are high relative to rates in other industrialized countries.

- Sex differences in eagerness to have sex can be explained in terms of differences in parental investment.

- An evolution-based theory, supported by correlational research, suggests that the presence or absence of a father at home may affect the sexual strategy—restraint or promiscuity—chosen by offspring.

494