13.3 Perceiving Ourselves and Others as Members of Groups

In the previous section you read of evidence that the self-concept is social in that others are involved in its construction: We see ourselves reflected in others’ reactions to us, and we understand ourselves by comparing our attributes with other people’s. But the self-concept is social in another sense as well: Others are not just involved in its construction; they are also part of its contents. We describe and think of ourselves not just in terms of our individual characteristics—I am short, adventurous, somewhat shy—but also in terms of the groups to which we belong and with which we identify—I am a French Canadian, Roman Catholic, member of the university marching band. Self-descriptions that pertain to the person as a separate individual are referred to as personal identity, and those that pertain to the social categories or groups to which the person belongs are referred to as social identity (Tajfel, 1972). In this section we examine some consequences of viewing ourselves and others in terms of the groups to which we and they belong.

Shifting Between Personal and Social Identities

20

What value might lie in our flexible capacity to think of ourselves in terms of both personal and social identities?

Our self-concepts are relatively consistent from situation to situation, but not rigid (Oakes et al., 1994). We think of ourselves differently at different times, in ways that help us meet the ever-changing challenges of social life. Sometimes, for some purposes, we find it most useful to think of our unique characteristics and motives: our personal identity. At other times, for other purposes, we find it more useful to think of ourselves as components of a larger unit, a group to which we belong: our social identity. Our evolution as a species has entailed a continuous balance between the need to assert ourselves as individuals and the need to cooperate with others (Guisinger & Blatt, 1994). To enable us to walk that tightrope, without falling into isolation on the one side or complete self-sacrifice to the group on the other, natural selection apparently endowed us with the capacity to hold both personal and social identities and to switch between them to meet our needs for survival.

In evolutionary history the groups with which people cooperated included some that were lifelong, such as the family and tribe, and others that were more short-lived, such as a hunting party organized to track down a particular antelope. Today the relatively permanent groups with which we identify may include our family, ethnic group, co-religionists, and occupational colleagues. The temporary groups include the various teams and coalitions with which we affiliate for particular ends, for periods ranging from minutes to years.

Different cultures in today’s world tend to vary in the relative weights they give to personal and social identity. As you might expect, individualist cultures emphasize personal identity, and collectivist cultures emphasize social identity. But the difference is relative. People everywhere can think of themselves in terms of both types of identity, to degrees that depend on the specific context and the problems they are dealing with at the time (Oyserman & Lee, 2008).

Consequences of Personal and Social Identity for Self-Esteem

Our feelings about ourselves depend not just on our personal achievements but also on the achievements of the groups with which we identify, even when we ourselves play little or no role in those achievements. Sports fans’ feelings about themselves rise and fall as “their” team wins and loses (Hirt et al., 1992). Similarly, people feel good about themselves when their town, university, or place of employment achieves high rank or praise.

523

21

Why is it that excellent performance by other members of our group can either lower or raise our self-esteem?

In some situations, the very same event—high achievement by other members of our group—can temporarily raise or lower our self-esteem, depending on whether our social identity or our personal identity is more active. When our social identity predominates, our group-mates are part of us, and we experience their success as ours. When our personal identity predominates, our group-mates are the reference group against which we measure our own accomplishments, so their success may diminish our view of ourselves. Social psychologists have demonstrated both these effects by priming people to think in terms of either their social or personal identities as they hear of high accomplishments by others in their group (Brewer & Weber, 1994; Gardner et al., 2002).

We mentioned earlier that students at highly selective schools think worse of themselves as scholars than do equally able students at less selective schools because of the difference in their relative standing in their reference group. At least one study indicates that this is true for those who think primarily in terms of their personal identities but not for those who think primarily in terms of their social identities (McFarland & Buehler, 1995). When the social identity is foremost, self-feelings are elevated, not diminished, by the excellent performance of group-mates. Graceful winners of individual achievement awards know this intuitively, and to promote good feelings and not incur jealousy, they activate their group-mates’ social identities by describing the award as belonging properly to the group as a whole.

Group-Enhancing Biases

22

According to Tajfel, why do we inflate our view of the groups to which we belong? How does a study of members of volleyball teams support Tajfel’s theory?

Other studies reveal that our bias to think highly of ourselves applies to our social identity as well as to our personal identity. In some conditions our group-enhancing biases are at least as strong as our self-enhancing biases (Bettencourt et al., 2001; Rubin & Hewstone, 1998). In fact, the concept of social identity first became prominent in social psychology when Henri Tajfel (1972, 1982) used it to explain people’s strong bias in favor of their own groups over other groups in all sorts of judgments. He argued that we exaggerate the virtues of our own groups to build up the part of our self-esteem that derives from our social identity.

Tajfel and others showed that group-enhancing biases occur even when there is no realistic basis for assuming that one group differs from another. In one laboratory experiment, people who knew they had been assigned to one of two groups by a purely random process—a coin toss—nevertheless rated their own group more positively than they did the other group (Locksley et al., 1980). You don’t need a degree in psychology to know that the fans of opposing baseball teams see the same plays differently, in ways that allow them all to leave the game believing that theirs was the better team, regardless of the score. Strike three is attributed by one group to the pitcher’s dazzling fastball and by the other to the umpire’s unacknowledged need for eyeglasses.

524

Some research has shown that group-enhancing biases increase when people are primed to think of their social identities and decline when people are primed to think of their personal identities. In one study, volleyball players attributed their team’s victories to their team’s great skill and their losses to external circumstances such as poor luck or bad officiating. This group-enhancing attributional bias disappeared, however, when the players underwent a self-affirmation procedure in which they listed their personal accomplishments in realms other than volleyball (Sherman & Kim, 2005). The self-affirmation presumably raised their self-esteem and primed them to think in terms of their personal rather than social identities, so they no longer felt motivated to think so highly of their team.

Stereotypes and Their Automatic Effects on Perception and Behavior

We can switch between personal and social identities in our perceptions of others as well as ourselves. When we view others in terms of their personal identities, we see them as unique individuals. When we view others in terms of their social identities, we gloss over individual differences and see all members of a group as similar to one another. This is particularly true when we view members of out-groups—that is, members of groups to which we do not belong.

The schema, or organized set of knowledge or beliefs, that we carry in our heads about any group of people is referred to as a stereotype. The first person to use the term stereotype in this way was the journalist Walter Lippmann (1922/1960), who defined it as “the picture in the head” that a person may have of a particular group or category of people. You may have stereotypes for men, women, Asians, African Americans, Californians, Catholics, and college professors. We gain our stereotypes largely from the ways our culture as a whole depicts and describes each social category. A stereotype may accurately portray typical characteristics of a group, or exaggerate those characteristics, or be a complete fabrication based on culture-wide misconceptions.

Stereotypes are useful to the degree that they provide us with some initial, valid information about a person, but they are also sources of prejudice and social injustice. Our stereotypes can lead us to prejudge others on the basis of the group to which they belong, without seeing their qualities as individuals. In the United States, research on stereotyping has focused primarily on European Americans’ stereotypes of African Americans, which are part and parcel of a long history of racial bias that began with the institution of slavery.

Distinction Between Implicit and Explicit Stereotypes

23

What is the distinction among public, private, and implicit stereotypes? What are two means by which researchers identify implicit stereotypes?

Many people in our culture today, particularly college students, are sensitized to the harmful effects of stereotypes, especially negative stereotypes about socially oppressed groups, and are reluctant to admit to holding them. Partly for that reason, social psychologists find it useful to distinguish among three levels of stereotypes: public, private, and implicit (Dovidio et al., 1994). The public level is what we say to others about a group. The private level is what we consciously believe but generally do not say to others. Both public and private stereotypes are referred to as explicit stereotypes because the person consciously uses them in judging other people. Such stereotypes are measured by questionnaires on which people are asked, in various ways, to state their views about a particular group, such as African Americans, women, or older adults. Responses on such questionnaires are easy to fake, but the hope is that research subjects who fill them out anonymously will fill them out honestly.

525

Implicit stereotypes, in contrast, are sets of mental associations that operate more or less automatically to guide our judgments and actions toward members of the group in question, even if those associations run counter to our conscious beliefs. Most psychological research on stereotyping today has to do with implicit stereotypes. These stereotypes are measured with tests in which the person’s attention is focused not on the stereotyped group per se, but on performing quickly and accurately an objective task that makes use of stimuli associated with the stereotype. Two types of tests commonly used in this way are priming tests and implicit association tests.

Priming as a Means of Assessing Implicit Stereotypes As discussed in Chapter 9, priming is a general method for measuring the strengths of mental associations. The premise underlying this method is that any concept presented to a person primes (activates) in the person’s mind the entire set of concepts that are closely associated with that concept. Priming the mind with one concept makes the related concepts more quickly retrievable from long-term memory into working memory.

In a test of implicit stereotypes about black people compared to white people, for example, subjects might, on each trial, be presented with a picture of either a black person’s face or a white person’s face and then with some adjective to which the person must respond as quickly as possible in a way that demonstrates understanding of the adjective’s meaning (Kawakami & Dovidio, 2001). For example, the required response might be to press one button if the adjective could describe a person and another button if it could describe a house but not a person. In some of these experiments the priming stimulus (the black or white face) that precedes the adjective is flashed very quickly on a screen—too quickly to be identified consciously but slowly enough that it can register in the subject’s unconscious mind and affect his or her thought processes.

Experiments of this sort have shown that white U.S. college students respond especially quickly to such words as lazy, hostile, musical, and athletic when primed with a black face, and especially quickly to such words as conventional, materialistic, ambitious, and intelligent when primed with a white face. Although positive and negative traits appear in both stereotypes, the experiments reveal that the implicit stereotypes that white students have of black people are significantly more negative than the ones they have of white people (Dovidio et al., 1986; Olson & Fazio, 2003).

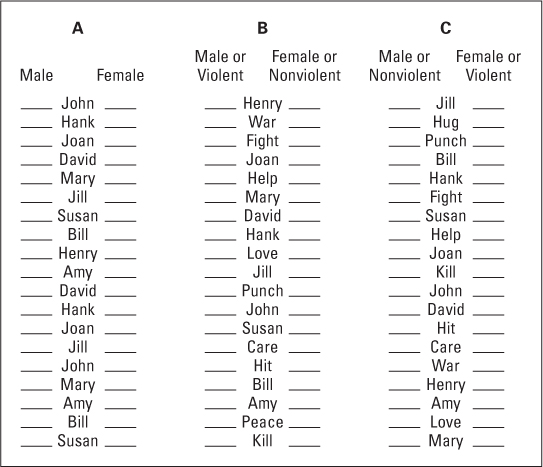

Implicit Association Tests Implicit association tests, developed initially by Anthony Greenwald and his colleagues (1998, 2002), take advantage of the fact that people can classify two concepts together more quickly if they are already strongly associated in their minds than if they are not strongly associated. To get an idea of how such a test works, complete the paper-and-pencil version that is presented in Figure 13.8, following the instructions in the caption. You will need a watch or clock that can count seconds to time yourself.

(Modeled after an example in Gladwell, 2005.)

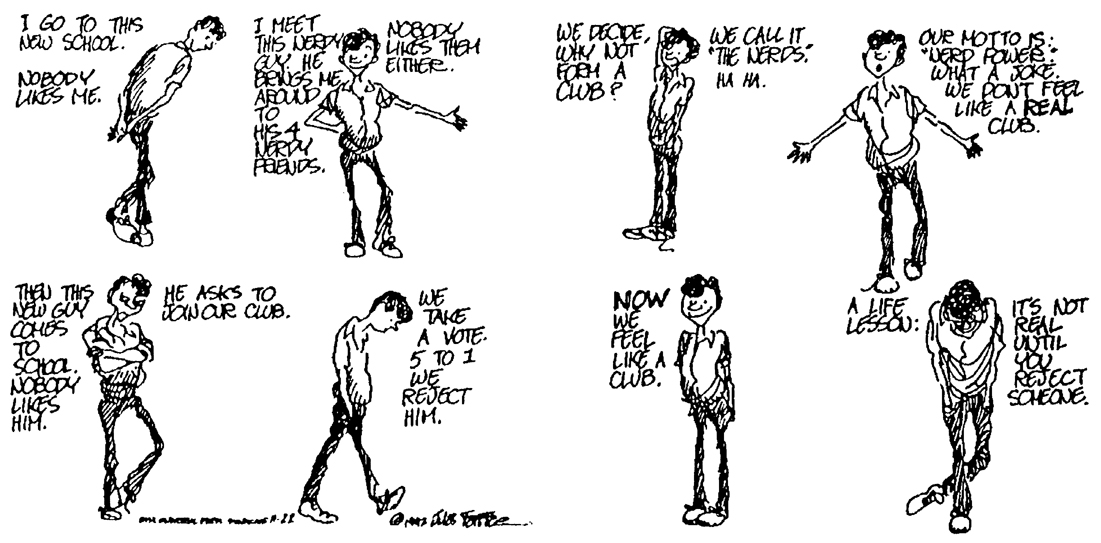

How did you perform? If you are like everyone we know who has taken this test, it took you longer to go through List C, where nonviolent terms are classified with male names and violent terms with female names, than it took you to go through List B, where violent terms go with male names and nonviolent terms with female names. Nearly everyone shares the stereotype that males are relatively violent and females are relatively nonviolent. Implicit association tests used in research are usually presented on a computer. Each individual stimulus appears on the screen, one at a time, and the person must respond by pressing one of two keys on the keyboard, depending on the category of the stimulus. If you wish to take such a test, you might find examples on the Internet at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit, where you can take part in an ongoing experiment involving implicit associations. (This site has been active for several years and may or may not still be active at the time that you are reading this.)

526

In implicit association tests having to do with race, a typical procedure is to use photographs of white and black faces, along with “good” words (such as love, happy, truth, terrific) and “bad” words (such as poison, hatred, agony, terrible) as the stimuli. In one condition, the job is to categorize white faces and “good” words together by pressing one key on the keyboard whenever one of them appears, and to classify black faces and “bad” words together by pressing another key whenever one of those appears. In the other condition, the job is to classify white faces and “bad” words together and black faces and “good” words together. The typical result is that white college students take about 200 milliseconds longer per key press, on average, in the latter condition than in the former (Aberson et al., 2004; Cunningham et al., 2001). White American children as young as 6 years of age perform similarly to adults (Baron & Banaji, 2006), and a same-race bias has also been found in Japanese children (Dunham et al., 2006), suggesting such a bias is universal and emerges early in development (see Dunham et al., 2008, for a review).

Implicit Stereotypes and Unconscious Discrimination

24

How have researchers shown that implicit stereotypes can lead to prejudicial behavior even in the absence of conscious prejudice?

Implicit stereotypes can lead people who are not consciously prejudiced to behave in prejudicial ways, despite their best intentions. In one series of studies, for example, white students’ scores on a test of implicit prejudice against black people correlated quite strongly with their subsequent reactions toward black conversation partners with whom they were paired (Dovidio et al., 1997, 2002). Those who scored highest in implicit prejudice spoke friendly words toward their black partners and believed they were behaving in a friendly way, but showed nonverbal signs of negativity or apprehension, which made them come across as unfriendly. They were less likely to make eye contact with their black partners, showed more rapid eye blinking, and were rated by their black partners and other observers as less friendly, despite their words, than were the students whose implicit prejudice scores were lower. None of these effects occurred when the conversation partners were white instead of black. In other studies, white people with high implicit prejudice toward black people exhibited neural and hormonal responses indicative of stress when interacting with a black partner, but not when interacting with a white partner (Mendes et al., 2007).

Implicit Stereotypes Can Be Deadly

Around midnight, on February 3, 1999, four plainclothes policemen saw a young black man, Amadou Diallo, standing on the stoop of his apartment building in the South Bronx, in New York City (Gladwell, 2005). He looked suspicious to them, so they stopped their unmarked cruiser and approached him. As they approached, he drew something from his pocket that looked to one of the officers like a gun. Reacting quickly, in self-defense, that officer shouted “gun” and all of the officers opened fire on Diallo and killed him instantly. When the officers looked more closely at the dead man they discovered that what he had drawn from his pocket was not a gun but his wallet. Diallo had apparently assumed that the four large, white, nonuniformed men approaching him with guns were intent on robbing him, so, seeing no route for escape, he had taken out his wallet.

527

25

What evidence suggests that implicit prejudice can cause police officers to shoot at black suspects more readily than at white suspects?

Would Diallo have been shot if he had been white? If he had been white, would the officers have seen him as suspicious and approached him in the first place? And if they had approached him, would they have mistaken his wallet for a gun? We can never know the answers as applied to this individual case, but there are grounds for believing that skin color can play a large role in such cases. Many research studies have shown that white people implicitly view unfamiliar black people as more hostile, violent, and suspicious looking than unfamiliar white people, and several experiments, inspired by the Diallo case and others like it, reveal that white people implicitly associate black faces more strongly with guns than they do white faces (Correll et al., 2002; Payne, 2006; Plant & Peruche, 2005).

Most such experiments have used college students as subjects, but one was conducted with actual police officers (Plant & Peruche, 2005). In this experiment, which involved computer simulations of self-defense situations, the instructions to each officer included the following words:

Today your task is to determine whether or not to shoot your gun. Pictures of people with objects will appear at various positions on the screen…. Some of the pictures will have the face of a person and a gun. These people are the criminals, and you are supposed to shoot at these people. Some of the pictures will have a face of a person and some other object (e.g., a wallet). These people are not criminals and you should not shoot at them. Press the “A” key for “shoot” and press the “L” key on the keyboard for “don’t shoot.” (p. 181)

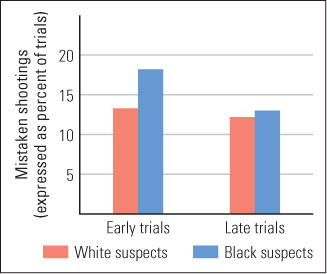

During the experiment, each picture appeared on the screen until the officer responded or until a 630-millisecond time limit had elapsed. As shown in Figure 13.9, during the first 80 trials the officers mistakenly shot unarmed black suspects significantly more often than they shot unarmed white suspects. With practice, during which they received immediate feedback as to whether they had shot an armed or unarmed person, they gradually overcame this bias. They did not show the bias during the final 80 trials of the 160-trial game. The researchers hope that such training will reduce officers’ bias in real-life encounters with criminal suspects.

Defeating Explicit and Implicit Negative Stereotypes

26

What sorts of learning experiences are most effective in reducing (a) explicit and (b) implicit prejudice?

Explicit and implicit stereotypes are psychologically quite different from each other. As you have seen, people often hold implicit stereotypes that do not coincide with their explicit beliefs about the stereotyped group. Whereas explicit stereotypes are products of conscious thought processes, modifiable by deliberate learning and logic, implicit stereotypes appear to be products of more primitive emotional processes, modifiable by such means as classical conditioning (Livingston & Drwecki, 2007). White people who have close black friends exhibit less implicit prejudice than do those without black friends (Aberson et al., 2004), and there is evidence that exposure to admirable black characters in literature, movies, and television programs can reduce implicit prejudice in white people (Rudman, 2004). Apparently, the association of positive feelings with individual members of the stereotyped group helps reduce automatic negative responses toward the group as a whole.

In one long-term study, Laurie Rudman and her colleagues (2001) found that white students who volunteered for a diversity-training course showed significant reductions in both explicit and implicit prejudice toward black people by the end of the course. However, the two reductions correlated only weakly with each other: Those students who showed the greatest decline in explicit prejudice did not necessarily show much decline in implicit prejudice, and vice versa. Further analysis revealed that those students who felt most enlightened by the verbal information presented in the course, and who reported the greatest conscious desire to overcome their prejudice, showed the greatest declines in explicit prejudice. In contrast, those who made new black friends during the course, or who most liked the African American professor who taught it, showed the greatest declines in implicit prejudice.

528

SECTION REVIEW

Social identity can be a major determinant of how we perceive ourselves and others.

Personal and Social Self-Identities

- We view ourselves in terms of both personal identity and social identity (the social categories or groups to which we belong). Individualist cultures emphasize personal identity, and collectivist cultures emphasize social identity.

- When social identity is uppermost in our minds, the success of others in our group boosts our self-esteem. When personal identity is uppermost, members of our group become our reference group, and their success can lower our self-esteem.

- Just as we have a self-enhancing bias, we have a group-enhancing bias, especially when our social identity predominates.

Implicit and Explicit Stereotypes

- Stereotypes—the schemas that we have about groups of people—can be explicit (available to consciousness) or implicit (unconscious but able to affect our thoughts, feelings, and actions). Implicit stereotypes are measured through priming and implicit association tests.

- Studies reveal that negative implicit stereotypes can promote prejudiced behavior even without conscious prejudice.

- Implicit prejudices are based on primitive emotional processes, modifiable by classical conditioning. Positive associations with members of the stereotyped group can help to reduce implicit prejudice.