13.4 Attitudes: Their Origins and Their Effects on Behavior

Thus far in this chapter we have been discussing the ways in which people evaluate other people and themselves. In doing so, we have been implicitly discussing attitudes. An attitude is any belief or opinion that has an evaluative component—a judgment or feeling that something is good or bad, likable or unlikable, moral or immoral, attractive or repulsive. Our attitudes tie us both cognitively and emotionally to our entire social world. We all have attitudes about countless objects, people, events, and ideas, ranging from our feelings about a particular brand of toothpaste to those about democracy or religion. Our most central attitudes, referred to as values, help us judge the appropriateness of whole categories of actions. In this final section of the chapter we examine some ideas about the effects and origins of attitudes.

Relationships of Attitudes to Behavior: Distinction Between Explicit and Implicit Attitudes

Social psychologists first began to study attitudes as part of their attempts to predict how individuals would behave in specific situations. They conceived of attitudes as mental guides that people use to make behavioral choices (Allport, 1935). Over the years much research has been conducted to determine the degree to which people’s attitudes do relate to their actual behavior and to understand the conditions in which that relationship is strong or weak. One clear finding is that the attitude-behavior relationship depends very much upon the way in which the attitude is assessed.

Earlier in this chapter, in the discussion of stereotypes, we distinguished between explicit and implicit racial attitudes. The same distinction applies to attitudes concerning all sorts of things: people, activities, objects, abstract concepts, and so forth. Explicit attitudes are conscious, verbally stated evaluations. They are measured by traditional attitude tests in which people are asked, in various ways, to state their evaluation of some object or form of behavior. For example, to assess explicit attitudes about eating meat, people might be asked to respond, on a scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, to items such as “In general, I like to eat meat.”

529

Implicit attitudes, by definition, are attitudes that are manifested in automatic mental associations (Fazio & Olson, 2003; Nosek, 2007). They are measured by implicit association tests, of the sort that we already described for assessing attitudes toward particular groups of people (refer back to Figure 13.8). If you can more quickly associate meat and meat-related words or pictures with good terms (such as wonderful) than with bad terms (such as terrible), then you have a positive implicit attitude toward meat. If the opposite is true, then you have a negative implicit attitude toward meat.

Implicit Attitudes Automatically Influence Behavior

27

What is the difference between implicit and explicit attitudes in their manner of influencing behavior?

Implicit attitudes are gut-level attitudes. The object of the attitude automatically elicits mental associations that connote “good” or “bad,” and these influence our bodily emotional reactions. In this sense, implicit attitudes automatically influence our behavior. The less we think about what we are doing, the more influence our implicit attitudes have. In contrast, our explicit attitudes require thought; the more we think about what we are doing, the more influence our explicit attitudes have. In many cases, people’s implicit and explicit attitudes coincide, and in those cases behavior generally corresponds well with attitude. But quite often, as we discussed in the case of racial attitudes, implicit and explicit attitudes do not coincide (Nosek, 2007).

Suppose you have become convinced that eating meat is a bad thing—bad for animals, bad for the planet, maybe bad for your health. You have developed, therefore, a negative explicit attitude toward eating meat. But suppose, from your long history of enjoying meat, you have a positive implicit attitude toward eating meat. If meat is put before you, your implicit attitude will win out unless you consciously think about your explicit attitude and use restraint. Your implicit attitude automatically makes you want to eat the meat. Not surprising, people who successfully maintain a vegetarian diet generally have negative implicit as well as negative explicit attitudes toward eating meat, and positive implicit as well as positive explicit attitudes toward eating vegetables (De Houwer & De Bruycker, 2007).

Experiments using fMRI have shown that people’s implicit attitudes are reflected directly in portions of the brain’s limbic system that are involved in emotions and drives. In contrast, explicit attitudes are reflected in portions of the prefrontal cortex that are concerned with conscious control. In cases where an explicit attitude counters an implicit attitude, the subcortical areas respond immediately to the relevant stimuli, in accordance with the implicit attitude, but then downward connections from the prefrontal cortex may dampen that response (Stanley et al., 2008). If you have a positive implicit but negative explicit attitude about eating meat, pleasure and appetite centers might respond immediately to meat put before you; but then, if you think about your explicit attitude, those responses might be overcome through connections from your prefrontal cortex.

Early Findings of Lack of Correlations Between Explicit Attitudes and Behavior

28

What early evidence and reasoning led some psychologists to suggest that attitudes have little effect on behavior?

Until relatively recently, all studies of attitudes in social psychology were studies of explicit attitudes. Thus it is perhaps not surprising that many of the earliest studies revealed a remarkable lack of correlation between measures of attitudes and measures of behavior. In one classic study, for instance, students in a college course filled out a questionnaire aimed at assessing their attitudes toward cheating, and later in the semester they were asked to grade their own true-false tests (Corey, 1937). The tests had already been graded secretly by the instructor, so cheating could be detected. The result was that a great deal of cheating occurred, and no correlation at all was found between the attitude assessments and the cheating. Those who had expressed the strongest anti-cheating attitudes on the questionnaire were just as likely to cheat in grading their own tests as were those who had expressed weaker anti-cheating attitudes. A strong correlation was found, however, between cheating and students’ true scores on the test: The lower the true score, the more likely the student was to try to raise it by cheating.

530

A number of findings such as this led some psychologists to conclude that attitudes play little or no role in guiding behavior (Wicker, 1969). Behavioral psychologists, such as B. F. Skinner (1957), who were already disposed to deny much relationship between thought and behavior, used such evidence to argue that attitudes are simply verbal habits, which influence what people say but are largely irrelevant to what they do. According to this view, people learn to say things like, “Honesty is the best policy,” because they are rewarded for such words by their social group. But when confronted by an inducement to cheat—such as the opportunity to raise a test score—their behavior is controlled by a new set of rewards and punishments that can lead to an action completely contrary to the attitude they profess.

Explicit Attitudes Must Be Retrieved from Memory to Affect Behavior

29

How might people improve their abilities to behave in accordance with their explicit attitudes?

A good deal of research has shown that people are most likely to behave in accordance with an explicit attitude if they are reminded of that attitude just before the behavioral test (Aronson, 1992; Glasman & Albarracín, 2006). In the experiment on cheating, those who cheated may have been immediately overwhelmed by their poor test performance, which reminded them strongly of their negative attitude toward getting a bad grade but did not remind them of their negative attitude toward cheating. Subsequent research suggests that with more time to think about their attitudes, or with more inducement to think about them, fewer students would have cheated and a correlation may have been found between their anti-cheating attitudes and their behavior.

If you are trying to behave in accordance with some newly formed explicit attitude, then you may need to exert considerable mental effort, at least for a while, to keep reminding yourself of your attitude. For example, if you are a recent convert to vegetarianism, but have a positive implicit attitude toward meat, you may need to remind yourself regularly of your explicit anti-meat attitude until your implicit attitude begins to change. With time, if you continue consciously to associate meat with negative images—perhaps images of cholesterol accumulating in your bloodstream or cattle being slaughtered—your implicit attitude may become more consistent with your explicit attitude. Then your chosen path will be easier.

The Origins of Attitudes, and Methods of Persuasion

People in our society devote enormous efforts and billions of dollars toward modifying other people’s attitudes. Advertising, political campaigning, and the democratic process itself (in which people speak freely in support of their views) are, in essence, attempts to change others’ attitudes—attitudes about everything from a brand of toothpaste to a war we are waging somewhere in the world. Here we shall examine some ideas about how attitudes are formed and how they are changed.

To a considerable degree, our attitudes are products of learning. Through direct experience or from information that others convey to us, we learn to like some objects, events, and concepts and to dislike others. Such learning can be automatic, involving no conscious thought, or, at the other extreme, it can be highly controlled, involving deliberate searches for relevant information and rational analysis of that information.

531

Attitudes Through Classical Conditioning: No Thought

Classical conditioning, a basic learning process discussed in Chapter 4, can be thought of as an automatic attitude generator. A new stimulus (the conditioned stimulus) is paired with a stimulus that already elicits a particular reaction (the unconditioned stimulus), and, as a result, the new stimulus comes to elicit, by itself, a reaction similar to that elicited by the original stimulus. Using the language of the present chapter, we can say that Pavlov’s dog entered the experiment with a pre-existing positive attitude toward meat. When Pavlov preceded the meat on several occasions with the sound of a bell, the dog acquired a positive attitude toward that sound. The dog now salivated and wagged its tail when the bell rang; we can extrapolate that, if given a chance, the dog would have learned to ring the bell itself.

30

How do advertisers use classical conditioning to influence people’s attitudes? How have researchers demonstrated effects of classical conditioning on implicit and explicit attitudes?

Classical conditioning leads us to feel positive about objects and events that have been linked in our experience to pleasant, life-promoting occurrences and to feel negative about those that have been linked to unpleasant, life-threatening occurrences. In today’s world, however, where many of the stimulus links we experience are the creations of advertisers and others who want to manipulate us, classical conditioning can have maladaptive consequences. All those ads in which fatty foods, beer, and expensive gas-guzzling cars are paired with beautiful people, happy scenes, and enjoyable music are designed to exploit our most thoughtless attitude-forming system, classical conditioning. The advertisers want us to salivate, wag our tails, and run out and buy their products.

Controlled experiments have shown that it is relatively easy to condition positive or negative attitudes to such products as a brand of mouthwash by pairing the product with positive or negative scenes or words (Grossman & Till, 1998). In some experiments, such conditioning has been demonstrated even when the subjects are not aware of the pairing of the conditioned and unconditioned stimuli (De Houwer et al., 2001; Olson & Fazio, 2001). Not surprising, such conditioning generally affects people’s implicit attitudes more than their explicit attitudes. In fact, some experiments have shown that it is possible to generate either a positive or negative implicit attitude through conditioning while, at the very same time, generating an opposite attitude through the presentation of evaluative statements.

Here’s an example of such an experiment (Rydell et al., 2006). Subjects were presented, over a series of conditioning trials, with a photograph of a man named Bob, which appeared on a screen in front of them. Immediately before each presentation of Bob, a word was flashed on the screen for just 25 milliseconds—too rapidly to read consciously but capable of being read at an unconscious level. For some subjects, each flashed word was negative, such as hate or death. For other subjects, the each flashed word was positive, such as love or party. In addition, on each trial, a verbal statement was presented along with the picture, which described something that Bob had done. This statement was on the screen long enough for subjects to read consciously, and subjects had to respond to the statement in a manner showing that they had read it and understood it. For subjects who were presented with negative conditioning words the statement about Bob’s behavior was always positive, and for subjects who were presented with positive conditioning words the statement about his behavior was always negative. Then the subjects were given both an implicit test and an explicit test of their attitudes toward Bob. In the implicit test they had to respond as quickly as possible in categorizing pictures of Bob with “good” terms on some trials and with “bad” terms on other trials. In the explicit test they rated how likeable Bob is, on a scale running from very unlikeable to very likeable.

The result, as predicted, was that the subjects manifested opposite implicit and explicit attitudes toward Bob. Their implicit attitudes were determined by the words flashed quickly on the screen, which unconsciously affected their mental associations about Bob. Their explicit attitudes were determined by the statements about Bob’s behavior, which they had read and thought about consciously.

Other experiments have shown that classical conditioning, when its effects aren’t countered with opposite statements, can affect explicit attitudes in the same direction as the implicit effects (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Li et al., 2007). When positive or negative images, words, or even smells are consistently paired with a photograph of a particular person or object, people develop a positive or negative implicit attitude toward that person or object. If they have no conscious information countering that attitude, the implicit attitude affects their explicit attitude. Other things being equal, we consciously like people and objects that elicit positive associations in our minds and consciously dislike those that elicit negative associations in our minds.

532

Attitudes Through Heuristics: Superficial Thought

31

What are some examples of decision rules (heuristics) that people use with minimal thought to evaluate messages?

Beyond simple classical conditioning is the more sophisticated but still relatively automatic process of using certain decision rules, or heuristics, to evaluate information and develop attitudes (Chen & Chaiken, 1999). Heuristics provide shortcuts to a full, logical elaboration of the information in a message. They are believed to affect primarily our explicit attitudes, but they can affect our implicit attitudes as well (Evans, 2008). Examples of such rules include the following:

- If there are lots of numbers and big words in the message, it must be well documented.

- If the message is phrased in terms of values that I believe in, it is probably right.

- Famous or successful people are more likely than unknown or unsuccessful people to be correct.

- If most people believe this message, it is probably true.

We learn to use such rules, presumably, because they often allow us to make useful judgments with minimal expenditures of time and mental energy. The rules become mental habits, which we use implicitly, without awareness that we are using them. Advertisers, of course, exploit these mental habits, just as they exploit the process of classical conditioning. They sprinkle their ads with irrelevant data and high-sounding words such as integrity, and they pay celebrities huge sums of money to endorse their products.

Attitudes Through Logical Analysis of the Message: Systematic Thought

Sometimes, of course, we think logically, in ways that produce rational effects on our explicit attitudes. Generally, we are most likely to do so for issues that really matter to us. In a theory of persuasion called the elaboration likelihood model, Richard Petty and John Cacioppo (1986) proposed that a major determinant of whether a message will be processed systematically (through logical analysis of the content) or superficially is the personal relevance of the message. According to Petty and Cacioppo, we tend to be cognitive misers; we reserve our elaborative reasoning powers for messages that seem most relevant to us, and we rely on mental shortcuts to evaluate messages that seem less relevant. Much research supports this proposition (Petty & Wegener, 1999; Pierro et al., 2004).

32

How did an experiment support the idea that people tend to reserve systematic thought for messages that are personally relevant to them and to use heuristics for other messages?

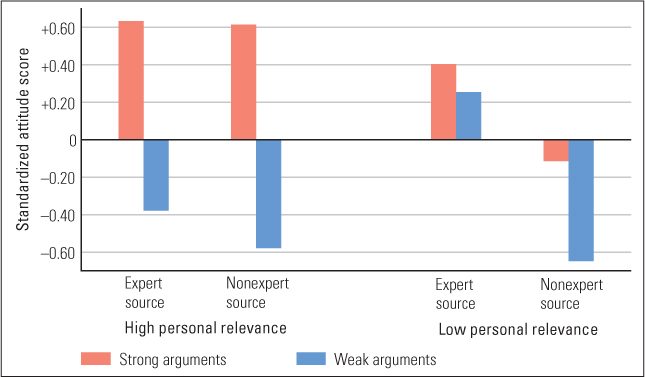

In one experiment on the role of personal relevance in persuasion, Petty and his colleagues (1981) presented college students with messages in favor of requiring students to pass a set of comprehensive examinations in order to graduate. Different groups of students received different messages, which varied in (a) the strength of the arguments, (b) the alleged source of the arguments, and (c) the personal relevance of the message. The weak arguments consisted of slightly relevant quotations, personal opinions, and anecdotal observations; the strong arguments contained well-structured statistical evidence that the proposed policy would improve the reputation of the university and its graduates. In some cases the arguments were said to have been prepared by high school students and in other cases by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. Finally, the personal relevance was varied by stating in the high-relevance condition that the proposed policy would take effect the following year, so current students would be subject to it, and in the low-relevance condition that it would begin in 10 years.

533

After hearing the message, students in each condition were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the proposal. Figure 13.10 shows the results. As you can see, in the high-relevance condition the quality of the arguments was most important. Students in that condition tended to be persuaded by strong arguments and not by weak ones, regardless of the alleged source. Thus, in that condition, students must have listened to and evaluated the arguments. In the low-relevance condition, the quality of the arguments had much less effect, and the source of the arguments had much more. Apparently, when the policy was not going to affect them, students did not attend carefully to the arguments but, instead, relied on the simple decision rule that experts (members of the Carnegie Commission) are more likely to be right than are nonexperts (high school students).

There is no surprise in Petty and Cacioppo’s theory or in the results supporting it. The idea that people think more logically about issues that directly affect them than about those that don’t was a basic premise of philosophers who laid the foundations for democratic forms of government. And, to repeat what is by now a familiar refrain, our mental apparatus evolved to keep us alive and promote our welfare in our social communities; it is no wonder that we use our minds more fully for those purposes than for purposes that have little effect on our well-being.

Attitudes as Rationalizations to Attain Cognitive Consistency

A century ago, Sigmund Freud began developing his controversial theory that human beings are fundamentally irrational. What pass for reasons, according to Freud, are most often rationalizations designed to calm our anxieties and boost our self-esteem. A more moderate view, to be pursued here, is that we are rational but the machinery that makes us so is far from perfect. The same mental machinery that produces logic can produce pseudo-logic.

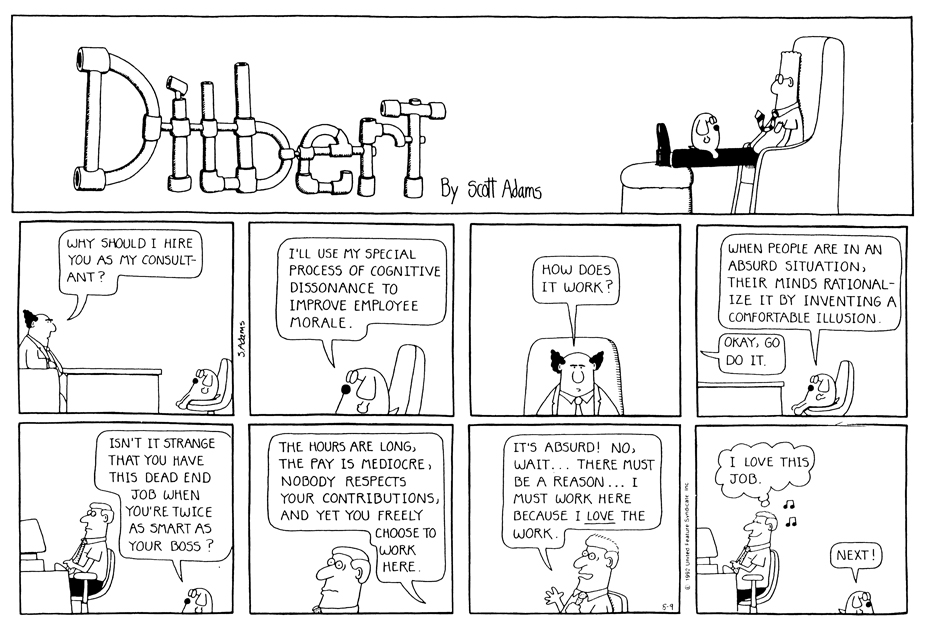

In the 1950s, Leon Festinger (1957) proposed what he called the cognitive dissonance theory, which ever since has been one of social psychology’s most central ideas (Cooper, 2012). According to the theory, we have a mechanism built into the workings of our mind that creates an uncomfortable feeling of dissonance, or lack of harmony, when we sense some inconsistency among the various explicit attitudes, beliefs, and items of knowledge that constitute our mental store. Just as the discomfort of hunger motivates us to seek food, the discomfort of cognitive dissonance motivates us to seek ways to resolve contradictions or inconsistencies among our conscious cognitions.

Such a mechanism could well have evolved to serve adaptive functions related to logic. Inconsistencies imply that we are mistaken about something, and mistakes can lead to danger. Suppose you have a favorable attitude about sunbathing, but you learn that overexposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays is the leading cause of skin cancer. The discrepancy between your pre-existing attitude and your new knowledge may create a state of cognitive dissonance. To resolve the dissonance in an adaptive way, you might change your attitude about sunbathing from positive to negative, or you might bring in a third cognition: “Sunbathing is relatively safe, in moderation, if I use a sunscreen lotion.” But the dissonance-reducing drive, like other drives, does not always function adaptively. Just as our hunger can lead us to eat things that aren’t good for us, our dissonance-reducing drive can lead us to reduce dissonance in illogical and maladaptive ways. Those are the effects that particularly intrigued Festinger and many subsequent social psychologists.

534

Avoiding Dissonant Information

33

How does the cognitive dissonance theory explain people’s attraction to some information and avoidance of other information?

I (Peter Gray) once heard someone cut off a political discussion with the words, “I’m sorry, but I refuse to listen to something I disagree with.” People don’t usually come right out and say that, but have you noticed how often they seem to behave that way? Given a choice of books or articles to read, lectures to attend, or documentaries to watch, people generally choose those that they believe will support their existing views. (This is becoming increasingly easy to do with respect to getting national and international news and political opinion, with the proliferation of television and Internet news sources aimed at people with specific political views. People get their information from news organizations that share their worldviews, making it less likely that they obtain an unbiased perspective on important issues.) That observation is consistent with the cognitive dissonance theory. One way to avoid dissonance is to avoid situations in which we might discover facts or ideas that run counter to our current views. If we avoid listening to or reading about the evidence that ultraviolet rays can cause skin cancer, we can blithely continue to enjoy sunbathing. People don’t always avoid dissonant information, but a considerable body of research indicates that they very often do (Frey, 1986; Jonas et al., 2001).

A good, real-world illustration of the avoidance of dissonant information is found in a research study conducted in 1973, the year of the Senate Watergate hearings, which uncovered illegal activities associated with then-President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign against George McGovern (Sweeney & Gruber, 1984). The hearings were extensively covered in all of the news media at that time. By interviewing a sample of voters before, during, and after the hearings, Sweeney and Gruber discovered that (a) Nixon supporters avoided news about the hearings (but not other political news) and were as strongly supportive of Nixon after the hearings as they had been before; (b) McGovern supporters eagerly sought out information about the hearings and were as strongly opposed to Nixon afterward as they had been before; and (c) previously undecided voters paid moderate attention to the hearings and were the only group whose attitude toward Nixon was significantly influenced (in a negative direction) by the hearings. So, consistent with the cognitive dissonance theory, all but the undecideds approached the hearings in a way that seemed designed to protect or strengthen, rather than challenge, their existing views.

Firming Up an Attitude to Be Consistent with an Action

34

How does the cognitive dissonance theory explain why people are more confident of a decision just after they have made it than just before?

We make most of our choices in life with less-than-absolute certainty. We vote for a candidate not knowing for sure if he or she is best, buy one car even though some of the evidence favors another, or choose to major in psychology even though some other fields have their attractions. After we have irrevocably made one choice or another—after we have cast our ballot, made our down payment, or registered for our courses and let the deadline for schedule changes pass—any lingering doubts would be discordant with our knowledge of what we have done. So, according to the cognitive dissonance theory, we should be motivated to set those doubts aside.

Many studies have shown that people do tend to set their doubts aside after making an irrevocable decision. Even in the absence of new information, people suddenly become more confident of their choice after acting on it than they were before. For example, in one study, bettors at a horse race were more confident that their horse would win if they were asked immediately after they had placed their bet than if they were asked immediately before (Knox & Inkster, 1968). In another study, voters who were leaving the polling place spoke more positively about their favored candidate than did those who were entering (Frenkel & Doob, 1976). In still another study, photography students who were allowed to choose one photographic print to keep as their own liked their chosen photograph better, several days later, if they were not allowed to revise their choice than if they were allowed to revise it (Gilbert & Ebert, 2002). In the reversible-choice condition, they could reduce dissonance by saying to themselves that they could exchange the photograph for a different one if they wanted to, so they had less need to bolster their attitude toward the one they had chosen.

535

Changing an Attitude to Justify an Action: The Insufficient-Justification Effect

Sometimes people behave in ways that run counter to their attitudes and then are faced with the dissonant cognitions, “I believe this, but I did that.” They can’t undo their deed, but they can relieve dissonance by modifying—maybe even reversing—their attitudes. This change in attitude is called the insufficient-justification effect, because it occurs only if the person has no easy way to justify the behavior, given his or her previous attitude.

35

In theory, why should the insufficient-justification effect work best when there is minimal incentive for the action and the action is freely chosen? How was this theory verified by two classic experiments?

One requirement for the insufficient-justification effect to occur is that there be no obvious, high incentive for performing the counter-attitudinal action. In a classic experiment that demonstrates the low-incentive requirement, Festinger and James Carlsmith (1959) gave college students a boring task (loading spools into trays and turning pegs in a pegboard) and then offered to “hire” them to tell another student that the task was exciting and enjoyable. Some students were offered $1 for their role in recruiting the other student, and others were offered $20 (a princely sum at a time when the minimum wage in the United States was $1 an hour). The result was that those in the $1 condition changed their attitude toward the task and later recalled it as truly enjoyable, whereas those in the $20 condition continued to recall it as boring. Presumably, students in the $1 condition could not justify their lie to the other student on the basis of the little money they were promised, so they convinced themselves that they were not lying. Those in the $20 condition, in contrast, could justify their lie: I said the task was enjoyable when it was actually boring, but who wouldn’t tell such a small lie for $20?

536

Another essential condition for the insufficient-justification effect is that subjects must perceive their action as stemming from their own free choice. Otherwise, they could justify the action—and relieve dissonance—simply by saying, “I was forced to do it.”

In an experiment demonstrating the free-choice requirement, students were asked to write essays expressing support for a bill in the state legislature that most students personally opposed (Linder et al., 1967). Students in the free-choice condition were told clearly that they didn’t have to write the essays, but they were encouraged to do so, and none refused. Students in the no-choice condition were simply told to write the essays, and all complied. After writing the essays, all students were asked to describe their personal attitudes toward the bill. Only those in the free-choice condition showed a significant shift in the direction of favoring the bill; those in the no-choice condition remained as opposed to it as did students who had not been asked to write essays at all.

In this case, attitude change in the free-choice condition apparently occurred because the students could justify their choice to write the essays only by deciding that they did, after all, favor the bill. Subsequent experiments, using essentially the same procedure, showed that students in the free-choice condition also exhibited more psychological discomfort and physiological arousal, compared to those in the no-choice condition, as they wrote their essays (Elkin & Leippe, 1986; Elliot & Devine, 1994). This finding is consistent with the view that they were experiencing greater dissonance.

SECTION REVIEW

An attitude is a belief or opinion that includes an evaluative component.

Attitudes and Behavior

- Implicit attitudes—those formed through direct experience or repeated associations—influence behavior automatically.

- Early research suggested that explicit attitudes correlate little if at all with actual behavior. Subsequent research indicates that explicit attitudes must be recalled and thought about before they can affect behavior.

Sources of Attitudes

- Implicit attitudes can be created or altered through classical conditioning, with no thought required and even without awareness.

- By using heuristics (such as “If most people believe this, it is probably true”), people can arrive at attitudes through superficial thought.

- When a message is highly relevant to us, we tend to base our explicit attitudes on logical analysis of the content.

Attitudes and Cognitive Dissonance

- We are motivated to reduce cognitive dissonance—a discomforting lack of accord among our explicit beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, and actions.

- The desire to prevent or reduce cognitive dissonance often leads people to avoid dissonant information and to set aside doubts about a decision once it has been made.

- When we freely and with little incentive do something contrary to an attitude, we may alter the attitude to better fit the action; this is called the insufficient-justification effect.