14.1 Effects of Being Observed and Evaluated

Let us begin by considering what might seem to be the minimal form of social pressure—the mere presence of other people who can observe us perform. We do not behave in exactly the same way when others can see us as we do when we are alone. As thinking, social beings, we are concerned about the impressions we make on other people, and that concern influences our behavior.

540

Facilitating and Interfering Effects of an Audience

In some of the earliest experiments in social psychology, people performed various tasks better when one or more observers were present than they did when alone. In one experiment, for example, college students who had achieved skill at a task involving eye–hand coordination (moving a handheld pointer to follow a moving target) subsequently performed it more accurately when observed by a group of graduate students than when tested alone (Travis, 1925). The enhancing effect of an audience on task performance was soon accepted as a general law of behavior and was given a name: social facilitation.

Other early experiments, however, demonstrated an opposite effect: social interference (also called social inhibition), a decline in performance when observers are present. For example, students who were asked to develop arguments opposing the views of certain classical philosophers developed better arguments when they worked alone than when they worked in the presence of observers (Allport, 1920). The presence of observers also reduced performance in solving math problems (Moore, 1917), learning a finger maze (Husband, 1931), and memorizing lists of nonsense syllables (Pressin, 1933).

Facilitation of “Easy” Tasks, Interference with “Hard” Ones

1

How does Zajonc’s theory explain both social facilitation and social interference? What evidence supports the theory?

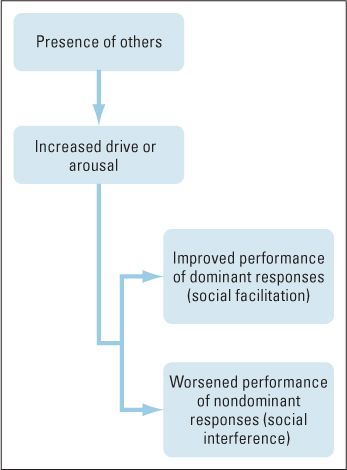

Why does an audience sometimes improve a person’s performance and other times worsen it? In reviewing the experiments, Robert Zajonc (rhymes with “science”) (1965) noticed that social facilitation usually occurred with relatively simple or well-learned tasks and that social interference usually occurred with complex tasks or tasks that involved new learning. From this observation, Zajonc proposed the following generalization: The presence of others facilitates performance of dominant actions and interferes with performance of nondominant actions. In this statement, the term dominant actions refers to actions that are so simple, species-typical, or well learned that they can be produced automatically, with little conscious thought; and nondominant actions refers to actions that require considerable conscious thought or attention.

To explain both effects, Zajonc further proposed that the presence of an audience increases a person’s level of drive or arousal (Aiello & Douthitt, 2001; Zajonc, 1965). The heightened drive increases the person’s effort, which facilitates dominant tasks where the amount of effort determines degree of success. The heightened drive interferes, however, with controlled, calm, conscious thought and attention and thereby worsens performance of nondominant actions (see Figure 14.1).

Much subsequent research has supported Zajonc’s theory. The presence of observers does increase drive and arousal, as measured by self-reports and by physiological indices such as increased heart rate and muscle tension (Cacioppo et al., 1990; Zajonc, 1980). Other studies have shown, just as Zajonc had predicted, that either facilitation or interference can occur in the very same task, depending on the performers’ skill. In one experiment, for example, expert pool players performed better when they were watched conspicuously by a group of four observers than when they thought they were not being observed, and the opposite occurred for novice pool players (Michaels et al., 1982).

541

Evaluation Anxiety as a Basis for Social Interference

2

What evidence suggests that evaluation anxiety is part of the causal chain of social interference?

Zajonc did not explain why a state of high drive interferes with performance of novel or cognitively difficult tasks, but a good deal of research since his time suggests that the primary cause is evaluation anxiety. Social interference increases when the observers are high in status or expertise and are present explicitly to evaluate (Geen, 1980, 1991). It also increases when subjects are made to feel unconfident and more anxious about their ability, through negative feedback given just before the test; and it decreases or is abolished when subjects are made to feel very confident about their ability (Klehe et al., 2007). Moreover, people who have an optimistic, unflappable, low-anxiety personality are more likely to exhibit social facilitation and less likely to exhibit social inhibition than are the rest of us (Uziel, 2007).

Choking Under Pressure: The Working-Memory Explanation

Social interference can be thought of as a subcategory of a more general phenomenon commonly referred to as choking under pressure. The highly aroused mental state produced by any strong form of pressure to perform well can, ironically, cause performance to worsen.

Using the terminology of modern cognitive psychology, “choking” is especially likely to occur with tasks that make strong demands on working memory. Working memory, as described in Chapter 9, is the part of the mind that controls conscious attention and holds, in consciousness, those items of information that are needed to solve a problem. The kinds of tasks that Zajonc referred to as involving nondominant responses are, in general, tasks that make heavy demands on working memory. Pressure and accompanying anxiety can worsen performance of such tasks by creating distracting thoughts—thoughts about being evaluated, about the difficulty of the task, about the consequences of failing, and so on—which usurp much of the limited capacity of working memory and thereby interfere with concentration on the problem to be solved.

Choking on Academic Tests

3

What evidence supports the view that choking on tests occurs because distracting thoughts interfere with working memory?

Students who suffer from severe test anxiety report that distracting and disturbing thoughts flood their minds and interfere with their performance on important tests (Zeidner, 1998). With sufficient pressure, such choking can occur even in students who normally do not suffer from test anxiety, and researchers have found that it occurs specifically with test items that make the highest demands on working memory.

In one series of experiments, for example, students were given math problems that varied in difficulty and in the degree to which students had an opportunity to practice them in advance (Beilock et al., 2004). Pressure to perform well was manipulated by telling some students that they were part of a team and that if they failed to perform above a certain criterion neither they nor their teammates—who had already performed above the criterion—would win a certain prize. They were also told that they would be videotaped as they worked on the problems, so that math teachers and professors could examine the problem-solving process. Students in the low-pressure group, in contrast, were simply asked to solve the problems as best they could. The result was that the high-pressure group performed significantly worse than the low-pressure group on the unpracticed difficult problems, but not on the easy or thoroughly practiced problems, which were less taxing on working memory.

542

Stereotype Threat as a Special Cause of Choking

4

How can the activation of a stereotype influence test performance? What evidence suggests that this effect, like other forms of choking, involves increased anxiety and interference with working memory?

Stereotype threat, a particularly potent cause of choking on academic tests, was first described several years ago by Claude Steele (1997; Steele et al., 2002). It is threat that test-takers experience when they are reminded of the stereotypical belief that the group to which they belong is not expected to do well on the test. In a series of experiments, Steele found that African American college students, but not white college students, performed worse on various tests if the tests were referred to as “intelligence tests” than if the same tests were referred to by other labels. He found, further, that this drop in performance became even greater if the students were deliberately reminded of their race just before taking the test. The threat in this case came from the common stereotype that African Americans have lower intelligence than white Americans. Essentially all African American college students are painfully aware of this stereotype.

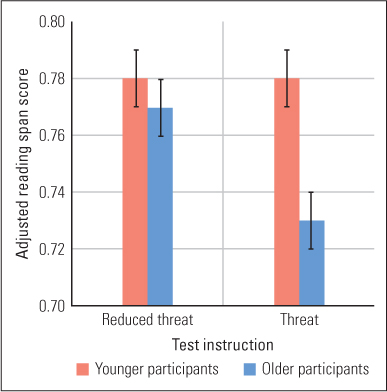

Subsequently, stereotype threat has been demonstrated with other stigmatized groups as well (Levy & Leifheit-Limson, 2009; Nguyen & Ryan, 2008; Schmader et al., 2008). For example, older adults perform worse on working-memory tests when they know they are being contrasted with a group of young adults (which is usually enough to produce a stereotype threat) than when they are told that the tasks are “age fair” and do not vary with age (Mazerolle et al., 2012; see Figure 14.2). In other situations, women consistently perform worse on problem-solving tests that are described as “math tests” than on the same tests when given other names, and this effect is magnified if attention is drawn to the stereotype that women have lower aptitude for math than do men (Johns et al., 2005; Wheeler & Petty, 2001). This effect has been observed in girls as young as 5 years (Ambady et al., 2001) and for elementary and middle-school children (Muzzatti & Agnoli, 2007). Even white males have been shown to exhibit stereotype threat in math, when the stereotype that whites have less math ability than do Asians is made salient to them (Aronson et al., 1999). The effect of stereotype threat is an example of what was described in Chapter 13 as a selffulfilling prophecy: The expectation that you will perform badly in fact causes you to perform badly.

As in the case of other examples of choking, stereotype threat seems to produce its effects by increasing anxiety and mental distraction. People report higher levels of felt anxiety and manifest greater physiological evidence of anxiety (such as heart-rate increase) when taking a test in the stereotype-threat condition than when taking the same test in the nonthreat condition (Johns et al., 2008; Osborne, 2007). The threat seems to undermine confidence, while at the same time increasing motivation to do well (so as not to confirm the stereotype), resulting in increased anxiety. The increased anxiety apparently reduces performance at least in part by occupying working memory with worrisome thoughts, thereby reducing the amount of working memory capacity available to solve the problems. Researchers have found that stereotype threat reduces performance on problems that tax working memory more than on problems that can be answered largely through recall from long-term memory (Beilock et al., 2007).

In case you yourself have suffered from stereotype threat, you may be interested to know that simple awareness of the stereotype-threat phenomenon helps people overcome it (Johns et al., 2005). Apparently, such awareness leads test-takers to attribute their incipient anxiety to stereotype threat rather than to the difficulty of the problems or to some inadequacy in themselves, and this helps them to concentrate on the problems rather than on their own fears. Other research has shown that self-affirming thoughts before the test—such as thoughts created by listing your own strengths and values—can reduce or abolish stereotype threat, apparently by boosting confidence and/or by reducing the importance attributed to the test (Martens et al., 2006).

543

Impression Management: Behavior as Performance

Besides influencing our abilities to perform specific tasks, social pressures influence our choices of what to say and do in front of other people. Because we care what others think of us, we strive to influence their thoughts. To that end, we behave differently when witnesses are present than when we are alone, and differently in front of some witnesses than in front of others. Social psychologists use the term impression management to refer to the entire set of ways by which people consciously and unconsciously modify their behavior to influence others’ impressions of them (Schlenker, 1980).

Humans as Actors and as Politicians

5

How do certain theatrical and political metaphors apply to impression management? Why do we, as intuitive politicians, want to look “good” to other people?

Poets and philosophers have always been aware of, and have frequently ridiculed, the human concern about appearances. As Shakespeare put it, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” The sociologist Erving Goffman developed an entire approach to thinking about human behavior based on this metaphor. In a classic book titled The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman (1959) portrayed us as actors, playing at different times on different stages to different audiences. In Goffman’s view, we are not necessarily aware that we are performing. Barry Schlenker and Beth Pontari (2000) expanded on this idea by suggesting that there need not be a division in our minds between the images we try to project and our sincere beliefs about ourselves. At any given moment we may simply be trying to exhibit our best self, or those aspects of our self that seem most appropriate and useful to meet the moment’s needs, which change with our audience.

An alternative metaphor, which captures long-range purposes of our performances, is that we are intuitive politicians (Tetlock, 1991, 2002). We perform in front of others not just to tell a good story or portray a character but also to achieve real-life ends that may be selfish or noble, or to some degree both. To do what we want to do in life, we need the approval and cooperation of other people—their votes, as it were—and to secure those votes, we perform and compromise in various ways. We are intuitive politicians in that we campaign for ourselves and our interests quite naturally, often without consciousness of our political ingenuity and strategies.

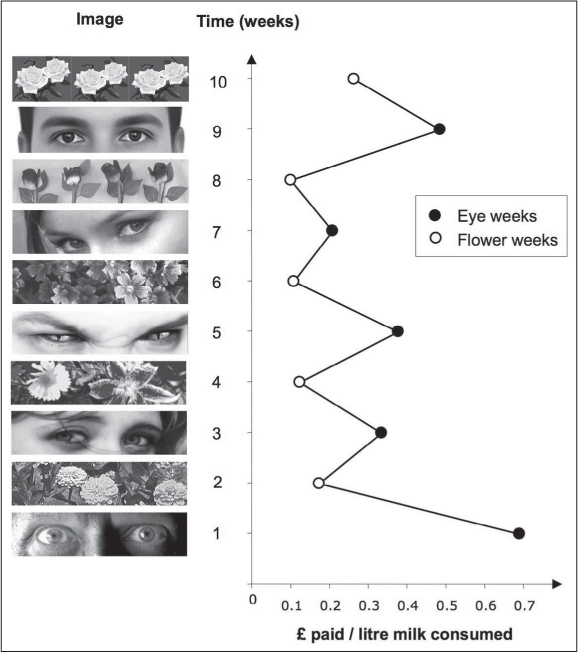

Depending on our needs, our capacities, and our audience, we may at any given time portray ourselves as pitiful, enraged, stern, or even irrational and unpredictable. These can be effective strategies for certain ends. For some people these strategies may even become regular ploys. But most of us, most of the time, try to make ourselves look good to other people. In fact, people are so sensitive to the attention of others that even photographs of a pair of eyes will influence their “moral” behavior (see Figure 14.3). We want to come across as attractive, friendly, competent, rational, trustworthy, and moral because we know that others will be more inclined to collaborate with us if they see those qualities in us than if they don’t. We also want to look modest, so people will think we are understating, not overstating, our virtues. We want to look sincere, not as if we are putting on a show or trying to ingratiate ourselves. And in general, we are more concerned with impression management with new acquaintances than with familiar friends and companions (Leary & Kowalski, 1995; Tice et al., 1995). We may or may not be conscious of our delicate balancing act between showing off and appearing modest, or between sincerity and ingratiation, but the act requires effort nevertheless (Vohs et al., 2005).

544

SECTION REVIEW

Social pressure affects our performance and leads us to try to control how others see us.

Effects of Having an Audience

- The presence of others can cause either social facilitation (improved performance) or social interference (worsened performance).

- The presence of others leads to heightened drive and arousal, which—in line with Zajonc’s theory—improves performance on dominant tasks and worsens performance on nondominant tasks.

- Evaluation anxiety is at least part of the cause of social interference.

Choking Under Pressure

- Pressure to perform well, on an academic test for example, can cause a decline in performance (choking).

- Choking occurs because pressure produces distracting thoughts that compete with the task itself for limited-capacity working memory.

- Stereotype threat is a powerful form of choking that occurs when members of a stigmatized group are reminded of stereotypes about their group before performing a relevant task.

Impression Management

- Because of social pressure, we consciously or unconsciously modify our behavior in order to influence others’ perceptions of us.

- This tendency to manage impressions has led social scientists to characterize us as actors, playing roles, or as politicians, promoting ourselves and our agendas.