15.1 Personality as Behavioral Dispositions, or Traits

What are the first three adjectives that come to mind concerning your own personality? Do they apply to you in all settings, or only in some? How clearly do they distinguish you from other people you know? Do you have any idea why you have those characteristics?

1

What is a trait, and how do traits differ from states? What does it mean to say that a trait is a dimension rather than an all-or-none characteristic?

The most central concept in personality psychology is the trait, which can be defined as a relatively stable predisposition to behave in a certain way. Traits are considered to be part of the person, not part of the environment. People carry their traits with them from one environment to another, although the actual manifestation of a trait in the form of behavior usually requires some perceived cue or trigger in the environment. For example, the trait of aggressiveness might be defined as an inner predisposition to argue or fight. That predisposition is presumed to stay with the person in all environments, but actual arguing or fighting is unlikely to occur unless the person perceives provocations in the environment. Aggressiveness or kindness or any other personality trait is, in that sense, analogous to the physical trait of “meltability” in margarine. Margarine melts only when subjected to heat (a characteristic of the environment); but some types of margarine need less heat to melt than others do, and that difference lies in the margarine, not in the environment.

It is useful to distinguish traits from states. States of motivation and emotion are, like traits, defined as inner entities that can be inferred from observed behavior. But while traits are enduring, states are temporary. In fact, a trait might be defined as an enduring attribute that describes one’s likelihood of entering temporarily into a particular state. The personality trait of aggressiveness describes the likelihood that a person will enter a belligerent state, much as the physical trait of meltability describes the likelihood that a brand of margarine will enter a liquid state.

Traits are not characteristics that people have or lack in all-or-none fashion but, rather, are dimensions (continuous, measurable characteristics) along which people differ by degree. If we measured aggressiveness or any other trait in a large number of people, our results would approximate a normal distribution, in which the majority are near the middle of the range and few are at the extremes (see Figure 15.1).

Traits describe differences among people in their tendencies to behave in certain ways, but they are not themselves explanations of those differences. To say that a person is high in aggressiveness simply means that the person tends to argue or fight a lot, in situations that would not provoke such behavior in most people. The trait is inferred from the behavior. It would be meaningless, then, for me to say that Harry argues and fights a lot because he is highly aggressive. That would be essentially the same as saying, “Harry argues and fights a lot because he argues and fights a lot”—an example of circular reasoning that does not prove anything.

575

Trait Theories: Efficient Systems for Describing Personalities

In everyday life we use an enormous number of personality descriptors. Gordon Allport (1937), one of the pioneers of personality psychology, identified 17,953 such terms in a standard English dictionary. Most of them have varying meanings, many of which overlap with the meanings of other terms. Consider, for example, the various connotations and overlapping meanings of affable, agreeable, amiable, amicable, companionable, congenial, convivial, cordial, friendly, genial, gracious, hospitable, kind, sociable, warmhearted, and welcoming. Personality psychologists have long been interested in devising a more efficient vocabulary for describing personality. The goal of any trait theory of personality is to specify a manageable set of distinct personality dimensions that can be used to summarize the fundamental psychological differences among individuals.

Factor Analysis as a Tool for Identifying an Efficient Set of Traits

In order to distill all the trait terms of everyday language down to a manageable number of meaningful, different dimensions of personality, trait theorists use a statistical technique called factor analysis. Factor analysis is a method of analyzing patterns of correlations in order to extract mathematically defined factors, which underlie and help make sense of those patterns. We will illustrate the technique here, with hypothetical data.

2

How is factor analysis used to identify trait dimensions that are not redundant with one another?

The first step in a factor-analytic study of personality is to collect data in the form of a set of personality measures taken across a large sampling of people. For example, the researcher might present a group of people with a set of adjectives and ask each person to indicate, on a scale of 1 to 5, the degree to which each adjective describes him- or herself. For the sake of simplicity, let us imagine a study in which just seven adjectives are used—carefree, compliant, dependable, hardworking, kind, rude, and trusting. To get a sense of what it is like to be a subject in such a study, you might rate yourself on each of these traits. For each term write a number from 1 to 5, depending on whether you think the term is (1) very untrue, (2) somewhat untrue, (3) neither true nor untrue, (4) somewhat true, or (5) very true of you as a person. Be honest in your ratings; you are doing this anonymously, as are the subjects in actual studies.

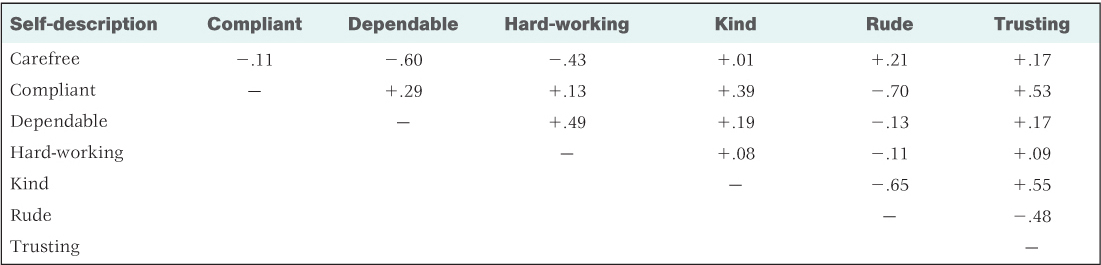

Once the data are collected, the researcher statistically correlates the scores for each adjective with those for each of the other adjectives, using the method of correlation described in Chapter 2. The result is a matrix of correlation coefficients, showing the correlation for every possible pair of scores (illustrated in Table 15.1).

Hypothetical matrix of correlations among adjectives used as personality self-descriptions

The next step in a factor analysis is a mathematically complex one called factor extraction, in which items (here adjectives) that are strongly related to one another, or that cluster together, are identified. For the data depicted in Table 15.1, such an analysis would identify two rather clear factors. One factor corresponds most closely with the adjectives carefree, dependable, and hardworking; and the other factor corresponds most closely with the adjectives compliant, kind, rude, and trusting. The final step is a subjective one, in which the researcher provides a label for the factors. In our hypothetical example, the factor that corresponds with carefree, dependable, and hardworking might be referred to as the conscientiousness dimension; and the factor that corresponds with compliant, kind, rude, and trusting might be referred to as the agreeableness dimension.

576

What the factor analysis tells us is that these two dimensions of personality are relatively independent of each other. People who are high in conscientiousness are about equally likely to be either high or low in agreeableness, and vice versa. Thus, conscientiousness and agreeableness are useful, efficient trait dimensions because they are not redundant with each other and because each captures at least part of the essence of a set of more specific trait terms.

Cattell’s Pioneering Use of Factor Analysis to Develop a Trait Theory

The first trait theory to be put to practical use was developed by Raymond Cattell (1950). Cattell’s undergraduate degree was in chemistry, and his goal in psychology was to develop a sort of chemistry of personality. Cattell argued that just as an infinite number of different molecules can be formed from a finite number of atoms, an infinite number of different personalities can be formed from a finite number of traits. To pursue this idea, he needed to identify the elements of personality (trait dimensions) and develop a way to measure them.

Cattell began his research by condensing Allport’s 17,953 English adjectives describing personality down to 170 that he took to be logically different from one another. He had large numbers of people rate themselves on each of these characteristics, and then he used factor analysis to account for patterns of correlation among the 170 different trait terms—a monumental task in the 1940s, before computers. Through this means, Cattell identified a preliminary set of traits and gave each a name. Then he developed various questionnaires aimed at assessing those traits in people and factor-analyzed the questionnaire results.

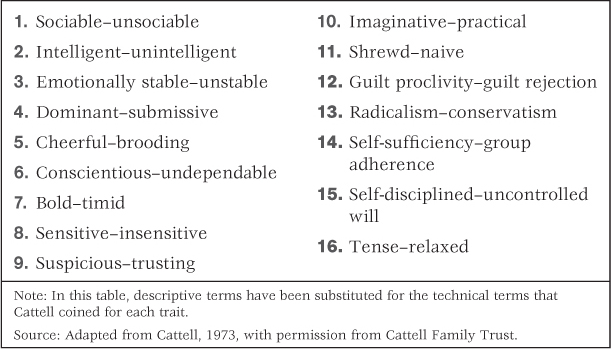

The upshot of Cattell’s research, which spanned many years, was the identification of 16 basic trait dimensions, listed in Table 15.2, and a questionnaire called the 16 PF Questionnaire to measure them (Cattell, 1950, 1973). (PF stands for personality factors) The questionnaire consists of nearly 200 statements about specific aspects of behavior, such as “I like to go to parties.” For each statement the respondent must select one of three possible answers—yes, occasionally, or no. The 16 PF Questionnaire is still sometimes used today, both as a clinical tool for assessing personality characteristics of clients in psychotherapy and as a research tool in studies of personality. (You may remember Cattell from Chapter 10 on Reasoning and Intelligence. Cattell used factor analytic techniques to identify two types of intelligence: fluid and crystallized, see p. 395.)

Cattell’s 16 source traits, or personality factors

577

The Five-Factor Model of Personality

3

Why is the five-factor model of personality generally preferred over Cattell’s trait theory today?

Many trait researchers find Cattell’s 16-factor theory to be overly complex, arguing that some of its factors are redundant. Indeed, even as Cattell was finalizing his theory, D. W. Fiske (1949) reported that many of Cattell’s personality traits correlated rather strongly with one another. Fiske’s reanalysis of Cattell’s data resulted in a five-factor solution. Although Fiske’s report lay in relative obscurity for many years, it was the first bit of evidence supporting a five-factor model of personality.

Today, with computers, it is much easier to perform large-scale factor-analytic studies than it was in Cattell’s time. Since the 1970s, hundreds of such studies have been done, with many different measures of personality and many different groups of subjects. Some studies have used self-ratings, based on adjectives or on responses to questions about behavior. Others have used ratings that people make of the personality of someone they know well rather than of themselves. Such studies have been conducted with children as well as with adults, and with people from many different cultures, using questionnaires translated into many different languages (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; McCrae & Allik, 2002; McCrae & Terracciano, 2005). Overall, the results have been fairly consistent in supporting what has become known as the five-factor model, or the Big Five theory, of personality.

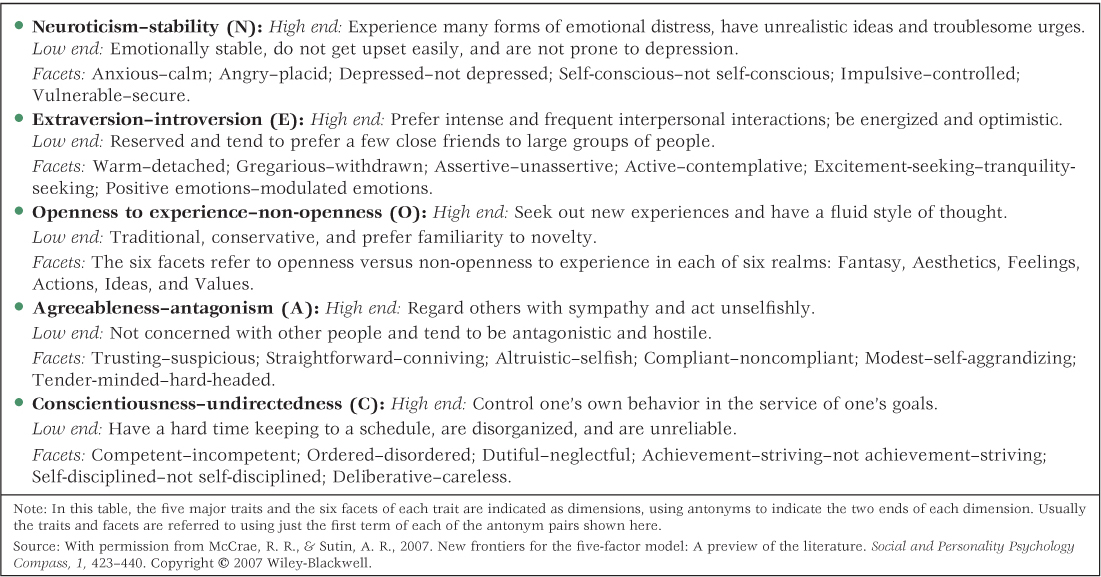

According to the model, a person’s personality is most efficiently described in terms of his or her score on each of five relatively independent global trait dimensions: neuroticism (vulnerability to emotional upset), extraversion (tendency to be socially outgoing), openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. (An easy way to remember the five factors is to observe that their initials spell the acronym OCEAN: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) Nearly all of the thousands of adjectives commonly used to describe personalities correlate at least to some degree with one or another of these five traits. The model also posits that each global trait dimension encompasses six subordinate trait dimensions referred to as facets of that trait (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). The facets within any given trait dimension correlate with one another, but the correlations are far from perfect. Thus, a detailed description of someone’s personality would include not just a score for each of the five global traits but also a score for each of the 30 facets. Table 15.3 presents a brief description of each of the Big Five trait dimensions and a list of the six facets for each.

The Big Five personality factors and their 30 facets

578

Measurement of the Big Five Traits and Their Facets

Trait theorists have developed many different questionnaires to assess personality. The questionnaire most often used to measure the Big Five traits and their facets is the NEO Personality Inventory (where N, E, and O stand for three of the five major traits), developed by Paul Costa and Robert McCrae (1992). This questionnaire is now in its third revision, referred to as the NEO-PI-3 (McCrae et al., 2005). In its full form, the person being tested rates 240 statements on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Each statement is designed to assess one facet of one of the five major traits.

For example, here are two statements from the NEO-PI-3 designed to assess the sixth facet (values) of openness to experience:

118. Our ideas of right and wrong may not be right for everyone in the world.

238. People should honor traditional values and not question them.

Agreement with the first statement and disagreement with the second would count toward a high score on the values facet of openness. In the development of such tests, trait theorists submit the results of trial tests to factor analysis and use the results to eliminate items whose scores do not correlate strongly (positively or negatively) with the scores of other items designed to measure the same facet.

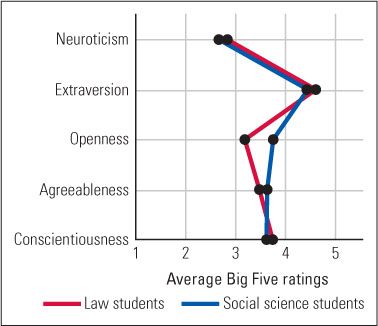

In recent years, shortened versions of the NEO-PI have been available on the Internet for self-testing. You can probably find one or more of these by searching “Big Five personality test” with Google or any other search engine. If you take such a test, you will get feedback regarding your results, and your data may also contribute to an ongoing research study. For one example of research findings using the NEO-PI, see Figure 15.2.

One problem with almost all personality questionnaires, which you will discover if you take such a test, is that the questions are quite transparent. A person who wants to present him- or herself as a particular kind of person can easily do so. The usefulness of the questionnaires depends on the honesty and insight of the respondent about his or her own behavior and emotions. In some research studies, and for some clinical purposes, personality inventories are filled out both by the person being evaluated and by others who know that person well. Agreement among the different ratings of the same person adds to the likelihood that the ratings are accurate.

The Relationship of Personality Measures to People’s Actual Behavior

4

How do researchers assess the validity of personality tests? What are some sample findings that show that measures of the Big Five personality traits are, to at least some degree, valid?

How valid are personality tests? As discussed in Chapter 2, a test is valid to the degree that its scores are true measures of the characteristics they are meant to measure. A personality test is valid to the degree that scores on each of its trait measures correlate with aspects of the person’s real-world behavior that are relevant to that trait. The validity of personality tests such as the NEO-PI has been supported by countless studies. Here are some examples of correlations between Big Five personality measures and actual behaviors:

- People who score high on neuroticism, compared to those who score lower, have been found to (a) pay more attention to, and exhibit better memory of, threats and other unpleasant information (Matthews et al., 2000); (b) manifest more distress when given a surprise math test (Schneider, 2004); (c) experience less marital satisfaction and greater frequency of divorce (Roberts et al., 2007); and (d) be much more susceptible to mental disorders, especially depression and anxiety disorders (Hettema et al., 2004).

- People who score high on extraversion, compared to those who score as introverts, have been found to (a) attend more parties and be rated as more popular (Paunonen, 2003); (b) be more often seen as leaders and achieve leadership positions (Anderson et al., 2001; Roberts et al., 2007); (c) live with and work with more people (Diener et al., 1992); and (d) be less disturbed by sudden loud sounds or other intense stimuli (Eysenck, 1990; Geen, 1984; Stelmack, 1990).

- People who score high on openness to experience, when compared to those who score lower, have been found to (a) be more likely to enroll in liberal arts programs rather than professional training programs in college (Paunonen, 2003); (b) change careers more often in middle adulthood (McCrae & Costa, 1985); (c) perform better in job training programs (Goodstein & Lanyon, 1999); (d) be more likely to play a musical instrument (Paunonen, 2003); and (e) exhibit less racial prejudice (Flynn, 2005).

- People who score high on agreeableness, compared to those who score lower, have been found to (a) be more willing to lend money (Paunonen & Ashton, 2001); (b) have fewer behavior problems during childhood (Laursen et al., 2002); (c) manifest less alcoholism or arrests in adulthood (Laursen et al., 2002); and (d) have more satisfying marriages and a lower divorce rate (Roberts et al., 2007).

- People who score high on conscientiousness, compared to those who score lower, have been found to (a) be more sexually faithful to their spouses (Buss, 1996); (b) receive higher ratings for job performance and higher grades in school (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006); and (c) smoke less, drink less, drive more safely, follow more healthful diets, and live longer (Friedman et al., 1995; Roberts et al., 2007).

All such findings demonstrate that people’s answers to personality test questions reflect, at least to some degree, the ways they actually behave and respond to challenges in the real world.

5

Why might personality traits be most apparent in novel situations or life transitions?

Personality differences do not reveal themselves equally well in all settings. When you watch people in familiar roles and settings, conforming to well-learned social norms—at their jobs, in the classroom, or at formal functions such as weddings and funerals—the common influence of the situation may override individual personality styles. Personality differences may be most clearly revealed when people are in novel, ambiguous, stressful situations and in life transitions, where cues as to what actions are appropriate are absent or weak (Caspi & Moffitt, 1991, 1993). As one pair of researchers put it, in the absence of cues as to how to behave, “the reticent become withdrawn, the irritable become aggressive, and the capable take charge” (Caspi & Moffitt, 1993, p. 250).

580

Continuity and Change in Personality Over Time

Does personality change significantly over time in one’s life, or is it stable? If you ever have the opportunity to attend the 25th reunion of your high school class, don’t miss it; it is bound to be a remarkable experience. Before you stands a person who claims to be your old friend Marty, whom you haven’t seen for 25 years. The last time you saw Marty, he was a skinny kid with lots of hair, wearing floppy sneakers and a sweatshirt. What you notice first are the differences: This Marty has a potbelly and very little hair, and he is wearing a business suit. But after talking with him for a few minutes, you have the almost eerie knowledge that this is the same person you used to play basketball with behind the school. The voice is the same, the sparkle in the eyes, the quiet sense of humor, the way of walking. And when it is Marty’s turn to stand up and speak to the group, he, who always was the most nervous about speaking before the class, is still most reluctant to do so. There’s no doubt about it—this Marty, who now has two kids older than he was when you last saw him, is the same Marty you always knew.

But that is all impression. Is he really the same? Perhaps Marty is in some sense your construction, and it is your construction that has not changed over the years. Or maybe it’s just the situation. This, after all, is a high school reunion held in your old school gymnasium, and maybe you’ve all been transported back in your minds and are coming across much more like your old selves than you normally would. Maybe you’re all trying to be the same kids you were 25 years ago, if only so that your former classmates will recognize you. Clearly, if we really want to answer the question of how consistent personality is over long periods, we’ve got to be more scientific.

The General Stability of Personality

6

What is the evidence that personality is relatively stable throughout adulthood? In what ways does personality tend to change with age?

Many studies have been conducted in which people fill out personality questionnaires, or are rated on personality characteristics by family members or friends, at widely separated times in their lives. The results indicate a rather high stability of personality throughout adulthood. Correlation coefficients on repeated measures of major traits (such as the Big Five) during adulthood typically range from .50 to .70, even with intervals of 30 or 40 years between the first and second tests (Costa & McCrae, 1994; Terracciano et al., 2006). Such stability apparently cannot be dismissed as resulting from a consistent bias in how individuals fill out personality questionnaires, as similar consistency is found even when the people rating the participants’ personalities are not the same in the second test as in the first (Mussen et al., 1980).

581

Such studies also indicate that personality becomes increasingly stable with increasing age up to about age 50, and it remains at a relatively constant level of stability after age 50 (Caspi et al., 2005; Terracciano et al., 2006). One analysis of many studies, for example, revealed that the average test-retest correlation of personality measures across 7-year periods was .31 in childhood, .54 during young adulthood, .64 at around age 30, and .74 between ages 50 and 70 (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Apparently, the older one gets, up to about age 50, the less one’s personality is likely to change. The older you are, the more like “yourself” you become. But some degree of change can occur at any age.

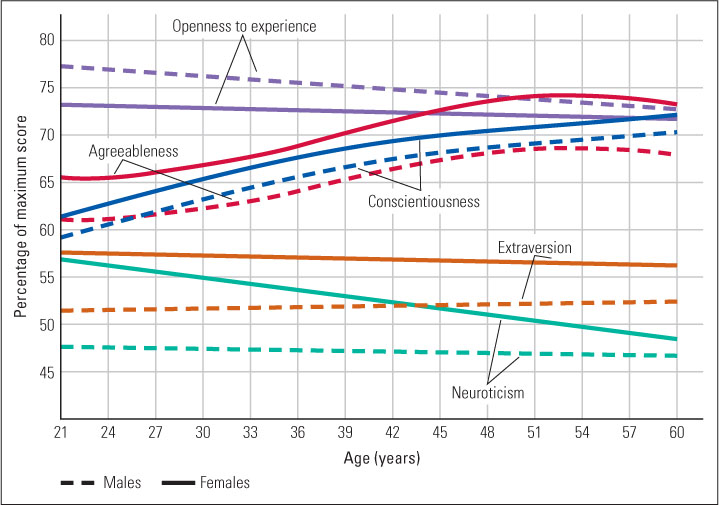

Patterns of Change in Personality with Age

Some of the changes in personality that occur with age are relatively consistent across samplings of individuals and constitute what is commonly thought of as increased maturity. Studies in many different cultures on measures of the Big Five indicate that, over the adult years, neuroticism and openness to experience tend to decline somewhat, and conscientiousness and agreeableness tend to increase somewhat (Caspi et al., 2005; Srivastava et al., 2003). Data from one such study are shown in Figure 15.3. Other studies show similar results, but suggest, contrary to the data in the figure, that agreeableness continues to increase even into and possibly beyond one’s 70s and 80s (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008; Weiss et al., 2005). Such findings are consistent with the general findings of increased life satisfaction in old age, discussed in Chapter 12.

(Based on data from Srivastava et al., 2003.)

In addition to the general age trends, other research indicates that an individual’s personality can change, at least to some degree, in any direction, at any age, in response to a major life change, such as a new career, an altered marital status, or the onset of a chronic illness (Helson & Stewart, 1994; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Other studies suggest that people who have a particular personality characteristic often make life choices that alter their personality even further in the pre-existing direction (Caspi et al., 2005; Roberts & Robins, 2004). For example, a highly extraverted person may choose a career that involves a lot of social activity, which may cause the person to become even more extraverted than before.

582

Genetic Foundations of Personality Traits

Where do traits come from? To some degree, at least, global traits such as the Big Five appear to derive from inherited physiological qualities of the nervous system.

The Heritability of Traits

7

How have researchers assessed the heritability of personality traits? What are the general results of such studies?

How heritable are personality traits? As discussed in Chapter 10, heritability refers to the degree to which individual differences derive from differences in genes rather than from differences in environmental experiences. Numerous research studies—using the methods described in Chapter 10—have shown that the traits identified by trait theories are rather strongly heritable. The most common approach in these studies has been to administer standard personality questionnaires to pairs of identical twins and fraternal twins (who are no more similar genetically than are ordinary siblings). The usual finding is that identical twins are much more similar than are fraternal twins on every personality dimension measured, similar enough to lead to an average heritability estimate of roughly .50 for most traits, including all of the Big Five (Bouchard, 2004; Bouchard & Loehlin, 2001). As explained in Chapter 10, a heritability of .50 means that about 50 percent of the variability among individuals results from genetic differences and the remaining 50 percent results from environmental differences.

In the past, such findings were criticized on the grounds that parents and others may treat identical twins more similarly than fraternal twins, and similar treatment may lead to similar personality. To get around that possibility, David Lykken and other researchers at the University of Minnesota gave personality tests to twins who had been separated in infancy and raised in different homes, as well as to twins raised in the same home (Bouchard, 1991, 1994; Tellegen et al., 1988). Their results were consistent with the previous studies: The identical twins were more similar to each other than were the fraternal twins on essentially every measure, whether they had been raised in the same home or in different homes, again leading to heritability scores averaging close to .50. Subsequent studies, by other researchers in several different countries, produced similar results (Plomin & Caspi, 1999).

Relative Lack of Shared Effects of the Family Environment

8

What evidence suggests that being raised in the same family does not promote similarity in personality?

In the past it was common for psychologists to attribute personality characteristics largely to the examples and training that people gain from their mothers and (to a lesser degree) their fathers (Harris, 1998). A common assumption was that people raised in the same family have similar personalities not just because of their shared genes but also because of their shared family environment. Perhaps the most surprising finding in the Minnesota study, confirmed since by other studies, is that this assumption is not true. Being raised in the same family has an almost negligible effect on measures of personality (Bouchard, 2004; Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000). Twin pairs who had been raised in different families were, on average, as similar to—and as different from—each other as were twin pairs who had been raised in the same family.

583

The contradiction between this finding and long-standing beliefs about the influence of parents is dramatically illustrated by some of the explanations that twins gave for their own behavioral traits (Neubauer & Neubauer, 1996, p. 21). When one young man was asked to explain his almost pathological need to keep his environment neat and clean, he responded, “My mother. When I was growing up she always kept the house perfectly ordered…. I learned from her. What else could I do?” When his identical twin brother, who had grown up in a different home in a different country but was also compulsively neat and clean, was asked the same question, he said, “The reason is quite simple. I’m reacting to my mother, who was a complete slob!” In this case the similarity of the twins in their compulsive tendency was almost certainly the result of their shared genetic makeup, yet each one blamed this tendency on his adoptive mother.

The results of such studies of twins do not necessarily mean that the family environment has no influence on personality development. The results do imply, however, that those aspects of the family environment that contribute to personality differentiation are typically as different for people raised in the same family as they are for people raised in different families. Two children raised in the same family may experience that environment very differently from each other.

In work done before the Minnesota twin study, Sandra Scarr and her colleagues (1981) came to a similar conclusion concerning the family environment through a different route. They compared nontwin, adopted children with both their biological siblings (raised in a different home) and with their adoptive siblings (raised in the same home) and found that they were far more similar to their biological siblings than to their adoptive siblings. In fact, for most personality measures, the adoptive siblings, despite being raised in the same home, were on average no more similar to each other than were any two children chosen at random. Later in the chapter we will examine some possible causes of the large individual differences in personality found among children raised in the same family.

Single Genes and the Physiology of Traits

9

How might variation in single genes influence personality?

It is reasonable to assume that genes affect personality primarily by influencing physiological characteristics of the nervous system. One likely route by which they might do so is through their influence on neurotransmission in the brain. In line with that view, several laboratories have reported significant correlations between specific personality characteristics and specific genes that alter neurotransmission.

The most consistently replicated such finding concerns the relationship between neuroticism and a gene that influences the activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain. This particular gene (called the 5-HTTLLPR gene, also discussed in Chapter 12) comes in two forms (alleles)—a short (s) form and a long (l) form. The general finding is that people who are homozygous for the l form (that is, have l on both paired chromosomes) are on average lower in neuroticism than are people who have at least one s allele (Gonda et al., 2009; Lesch, 2003; Schmitz et al., 2007). Serotonin is known to play a role in brain processes involved with emotional excitability, so it is not surprising that variations in serotonin might affect neuroticism.

Other researchers have found a significant relationship between the trait of novelty seeking—a more assertive form of openness to experience, which includes elements of impulsiveness, excitability, and extravagance—and alleles that alter the action of the neurotransmitter dopamine (Benjamin et al., 1996, 1998; Lahti et al., 2006; Golimbet et al., 2007). As noted in Chapter 6, dopamine is involved in reward and pleasure systems in the brain, so it is not surprising that alterations in dopamine might affect behaviors that have to do with pleasure seeking.

584

Such effects are relatively small, and they are not seen in all populations. Variation in personality no doubt derives from the combined effects of many genes interacting with influences of the environment. The effect that any specific gene has on an individual’s personality may depend on the mix of other genes that the person carries and on the person’s environmental experiences.

SECTION REVIEW

The trait—a relatively stable behavioral predisposition—is a key concept in personality.

Trait Theories

- Factor analysis provides a mathematical means to identify personality traits. Each trait is a continuous dimension, not an all-or-none characteristic.

- Raymond Cattell pioneered this approach, producing a theory with 16 basic traits.

- The most widely accepted trait theory today posits five major traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), each with six subordinate traits called facets.

- Questionnaires designed to measure individuals on the Big Five traits or other traits all require honesty and insight from the respondent to yield accurate results.

Predictive Value of Traits

- All of the Big Five traits have been shown to predict behavior at better-than-chance levels, which helps to establish the validity of the personality measures.

- Studies show that adult personality is relatively stable and becomes more stable with age. Correlation coefficients for repeated tests, even many years apart, range from .50 to .70.

- Personality does change, however. Increased age is typically accompanied by increased conscientiousness and agreeableness and decreased neuroticism and openness to experience.

- An individual’s personality can change to some extent in any direction at any age in response to life changes.

Genetic Basis of Traits

- Studies comparing pairs of identical and fraternal twins yield heritability estimates for personality averaging about .50.

- The personalities of biological relatives raised in the same family are generally no more similar than those of equally related people raised apart.

- Researchers are searching, with moderate success, for specific gene alleles that contribute to particular traits.