16.5 Schizophrenia

John sits alone in his dismal room, surrounded by plastic bags of garbage that he has hoarded during late-night excursions onto the street. He is unkempt and scrawny. He has no appetite and hasn’t eaten a proper meal in weeks. He lost his job months ago. He is afraid to go out during the day because he sees in every passing face a spy who is trying to learn, by reading his mind, the secret that will destroy him. He hears voices telling him that he must stay away from the spies, and he hears his own thoughts as if they were broadcast aloud for all to hear. He sits still, trying to keep calm, trying to reduce the volume of his thoughts. John’s disorder is diagnosed as schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a serious disorder that is found in roughly 0.7 percent of people at some time in their lives (Tandon et al., 2008). It accounts for a higher percentage of the in-patient population of mental hospitals than do disorders in any other diagnostic category. The disorder is somewhat more prevalent in men than in women, and it also typically strikes earlier and is more severe in men than in women (Taylor & Langdon, 2006). It usually first manifests itself in late adolescence or early adulthood, and the average age for first diagnosis is about 4 years later in women than in men (Riecher-Rossler & Hafner, 2000). Sometimes people make a full recovery from schizophrenia, sometimes they make a partial recovery, and sometimes the disorder takes a deteriorating course throughout the person’s life.

The label schizophrenia was first used by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler (1911/1950), whose writings are still a valuable source of information and insight about the disorder. Bleuler believed, as do many theorists today, that schizophrenia entails a split among such mental processes as attention, perception, emotion, motivation, and thought, such that these processes operate in relative isolation from one another, leading to bizarre and disorganized thoughts and actions. The term comes from the Greek words schizo, which means “split,” and phrenum, which means “mind,” so it literally means “split mind.” However, schizophrenia does not refer to “being of two minds” or having a “split (or multiple) personality,” even though laypersons and the popular media sometimes misuse the term in that way.

Diagnostic Characteristics of Schizophrenia

No two sufferers of schizophrenia have quite the same symptoms. But to receive the DSM-5 diagnosis of schizophrenia, the person must manifest a serious decline in ability to work, care for him- or herself, and connect socially with others (Figueira & Brissos, 2011). The person must also manifest, for at least 1 month, two or more of the following five categories of symptoms: disorganized thought and speech, delusions, hallucinations, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms—all described in this section. These symptoms are usually not continuously present; the person typically goes through episodes of active phases of the disorder, lasting for weeks or months, separated by periods of comparative normalcy.

Disorganized Thought and Speech

23

What are the five main classes of symptoms of schizophrenia?

Many people with schizophrenia show speech patterns that reflect an underlying deficit in the ability to think in a logical, coherent manner. In some cases, thought and speech are guided by loose word associations. A classic example is this greeting to Bleuler (1911/1950) from one of his patients: “I wish you a happy, joyful, healthy, blessed and fruitful year, and many good wine-years to come as well as a healthy and good apple-year, and sauerkraut and cabbage and squash and seed year.” Once the patient’s mind hooked onto fruit (in “fruitful year”), it entered into a chain of associations involving fruits and vegetables that had little to do with the original intent of the statement.

In all sorts of formal tests of logic, people with schizophrenia do poorly when in an active phase of their disorder (Docherty et al., 2003; Simpson & Done, 2004). They often encode the problem information incorrectly, fail to see meaningful connections, or base their reasoning on superficial connections having more to do with the sounds of words than with their meanings. People may show disorganized speech or thought long before other symptoms of schizophrenia are apparent (Goldberg et al., 2011).

646

Delusions

A delusion is a false belief held in the face of compelling evidence to the contrary. Common types of delusions in schizophrenia are delusions of persecution, which are beliefs that others are plotting against one; delusions of being controlled, such as believing that one’s thoughts or movements are being controlled in puppet-like fashion by radio waves or invisible wires; and delusions of grandeur, which are beliefs in one’s own extraordinary importance—for example, that one is the queen of England or is the love object of a famous movie star.

Delusions may result, in part, from a fundamental difficulty in identifying and remembering the original source of ideas or actions (Moritz et al., 2005). For example, delusions of being controlled may derive from a failure to mentally separate voluntary actions from involuntary actions; people with schizophrenia may often find themselves performing actions without remembering that they willfully initiated those actions (Broome et al., 2005). Delusions of persecution may stem, in part, from attempts to make sense of their horrible feelings and confusion. Delusions of grandeur may derive from an inability to separate fantasies from real-world experiences. Moreover, all sorts of delusions may be buttressed by deficits in logical reasoning, as in the case of a woman who supported her claim to be the Virgin Mary this way: “The Virgin Mary is a virgin. I am a virgin. Therefore, I am the Virgin Mary” (Arieti, 1966).

Hallucinations

Hallucinations are false sensory perceptions—hearing or seeing things that aren’t there. By far the most common hallucinations in schizophrenia are auditory, usually the hearing of voices. Hallucinations and delusions typically work together to support one another. For example, a man who has a delusion of persecution may repeatedly hear the voice of his persecutor insulting or threatening him.

A good deal of evidence supports the view that auditory hallucinations derive from the person’s own intrusive verbal thoughts—thoughts that others of us would experience as disruptive but self-generated. People with schizophrenia apparently “hear” such thoughts as if they were broadcast aloud and controlled by someone else. When asked to describe the source of the voices, they typically say that they come from inside their own heads, and some even say that the voices are produced, against their will, by their own speech mechanisms (Smith, 1992). Consistent with these reports, people with schizophrenia can usually stop the voices by such procedures as humming, counting, or silently repeating a word—procedures that, in everyone, interfere with the ability to imagine vividly any sounds other than those that are being hummed or silently recited (Bick & Kinsbourne, 1987; Reisberg et al., 1989). In addition, brain-imaging research, using fMRI, has revealed that verbal hallucinations in people with schizophrenia are accompanied by neural activity in the same brain regions that are normally involved in subvocally generating and “hearing” one’s own verbal statements (Allen et al., 2008; Shergill et al., 2004).

Grossly Disorganized Behavior and Catatonic Behavior

Not surprising, given their difficulties with thoughts and perceptions, people in the active phase of schizophrenia often behave in very disorganized ways. Many of their actions are strikingly inappropriate for the context—such as wearing many overcoats on a hot day or giggling and behaving in a silly manner at a solemn occasion. The inability to keep context in mind and to coordinate actions with it seems to be among the basic deficits in schizophrenia (Broome et al., 2005). Even when engaging in appropriate behaviors, such as preparing a simple meal, people with schizophrenia may fail because they are unable to generate or follow a coherent plan of action.

647

In some cases, schizophrenia is marked by catatonic behavior, defined as behavior that is unresponsive to the environment (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Catatonic behavior may involve excited, restless motor activity that is not directed meaningfully toward the environment; or, at the other extreme, it may involve a complete lack of movement for long periods—a form referred to as a catatonic stupor. Such behaviors may be means of withdrawing from a world that seems frighteningly difficult to understand or control.

Negative Symptoms

The so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia are those that involve a lack of, or reduction in, expected behaviors, thoughts, feelings, and drives (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). They include a general slowing down of bodily movements, poverty of speech (slow, labored, unspontaneous speech), flattened affect (reduction in or absence of emotional expression), loss of basic drives such as hunger, loss of the pleasure that normally comes from fulfilling drives, and social withdrawal (Birkett et al., 2011; Gard et al., 2011; Pinkham et al., 2012). Although you might expect catatonic stupor to be included in the category of negative symptoms, it is usually not, because the stupor is believed to be actively maintained.

The majority of people with schizophrenia manifest negative symptoms to some degree, and for many these are the most prominent symptoms. I (Peter Gray) once asked a dear friend, who was suffering from schizophrenia and was starving himself, why he didn’t eat. His answer, in labored but thoughtful speech, was essentially this: “I have no appetite. I feel no pleasure from eating or anything else. I keep thinking that if I go long enough without eating, food will taste good again and life might be worth living.” For him, the most painful symptom of all was an inability to experience normal drives or the pleasure of satisfying them.

Neurological Factors Associated with Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is characterized primarily as a cognitive disorder, brought on by deleterious changes in the brain (Broome et al., 2005; Heinrichs, 2005). People with schizophrenia appear to suffer from deficits in essentially all the basic processes of attention and memory that were discussed in Chapter 9 (Dickinson et al., 2008; Reichenberg & Harvey, 2007). They perform particularly poorly at tasks that require sustained attention over time or that require them to respond only to relevant information and to ignore irrelevant information (Bozikas et al., 2005; K. Wang et al., 2005). They are abnormally slow at bringing perceived information into their working-memory stores, and poor at holding onto the information once it is there (Barch, 2003; Fuller et al., 2005). All these and other kinds of mental deficits appear to contribute to the whole set of diagnostic symptoms of schizophrenia—the disordered thought, delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behavior, and negative symptoms (Broome et al., 2005).

Disruptions in Brain Chemistry

24

What early evidence supported the dopamine theory of schizophrenia? Why is the simple form of that theory doubted today?

By the early 1970s evidence had accrued for the dopamine theory of schizophrenia—the theory that schizophrenia arises from too much activity at brain synapses where dopamine is the neurotransmitter. The most compelling evidence was the observation that the clinical effectiveness of drugs in reducing the positive symptoms of schizophrenia was directly proportional to the drug’s effectiveness in blocking dopamine release at synaptic terminals (Seeman & Lee, 1975). Other support came from the finding that drugs such as cocaine and amphetamine, which increase the action of dopamine in the brain, can greatly exacerbate the symptoms of schizophrenia in people with the disorder and, at higher doses, can even induce such symptoms in people who do not have the disorder (see Abi-Dargham & Grace, 2011).

648

Today, researchers continue to recognize the role of dopamine in schizophrenia but generally do not accept the original, simple form of the dopamine theory. One major flaw in the theory is that it does not explain the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, which are not well treated by drugs that act solely on dopamine and are not typically exacerbated by drugs that increase that action of dopamine. Modern theories suggest that schizophrenia may involve unusual patterns of dopamine activity. Overactivity of dopamine in some part of the brain, especially in the basal ganglia, may promote the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, and underactivity of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex may promote the negative symptoms (Stone et al., 2007).

Currently, a good deal of attention is being devoted to the role of glutamate in schizophrenia (Javitt, 2010; Schobel et al., 2013). Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter at fast synapses throughout the brain. Some research suggests that one of the major receptor molecules for glutamate is defective in people who have schizophrenia, resulting in a decline in the effectiveness of glutamate neurotransmission (Javitt & Coyle, 2004; Phillips & Silverstein, 2003). Such a decline could account for the general cognitive debilitation that characterizes the disorder. Consistent with this theory, the dangerous, often-abused drug phencyclidine (PCP)—known on the street as “angel dust”—interferes with glutamate neurotransmission and is capable of inducing the full range of schizophrenic symptoms, including the negative and disorganized symptoms as well as hallucinations and delusions, in otherwise normal people (Javitt & Coyle, 2004).

Alterations in Brain Structure

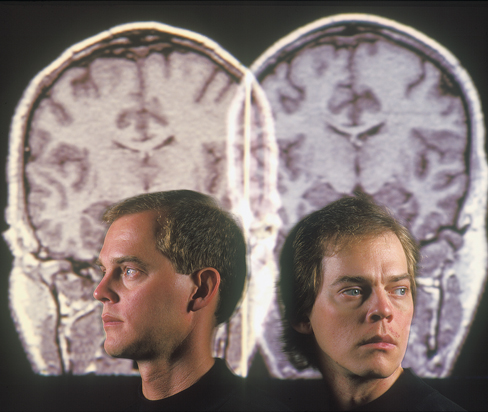

Studies using brain-imaging techniques have shown structural differences between the brains of people with schizophrenia and those of other people (Hartberg et al., 2011; Keshavan et al., 2008). The most common finding is enlargement of the cerebral ventricles (fluid-filled spaces in the brain) accompanied by a reduction in neural tissue surrounding the ventricles. Some researchers have detected abnormal blood flow—either too much or too little—to certain areas of the brain in some patients with schizophrenia (Lawrie & Pantelis, 2011; Walther et al., 2011). Decreased neural mass has been found in various parts of the brain, especially the hippocampus (involved in memory) and the prefrontal cortex (involved in all sorts of conscious control of thought and behavior). These size differences are relatively small and vary from person to person; they are not sufficiently reliable to be useful in diagnosing the disorder (Heinrichs, 2005; Keshavan et al., 2008).

25

How might an exaggeration of a normal developmental change at adolescence help bring on schizophrenia?

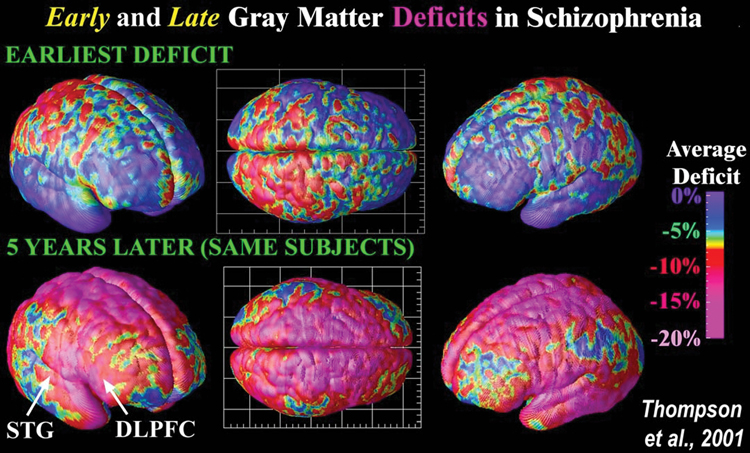

Some researchers have attempted to explain the timing of the onset of schizophrenia in terms of maturational changes in the brain. During adolescence, the brain normally undergoes certain structural changes: Many neural cell bodies are lost, a process referred to as pruning, and many new neural connections grow. The result is a decrease in gray matter (masses of cell bodies) and an increase in white matter (bundles of axons running from one brain area to another) (see Figure 16.7). Some researchers have suggested that an abnormality in pruning, which leads to the loss of too many cell bodies, may underlie at least some cases of schizophrenia (Keshavan et al., 2006; Lewis & Levitt, 2002). Consistent with this view, neuroimaging studies of people at risk for schizophrenia revealed a larger decline in gray matter during adolescence or early adulthood in those who subsequently developed the disorder than in those who did not (Lawrie et al., 2008).

649

Genetic and Environmental Causes of Schizophrenia

Why do the neural and cognitive alterations that bring on and constitute schizophrenia occur in some people and not in others? Genetic differences certainly play a role, and environmental differences do, too.

Predisposing Effects of Genes

25

How do the varying rates of concordance for schizophrenia among different classes of relatives support the idea that heredity influences one’s susceptibility for the disorder?

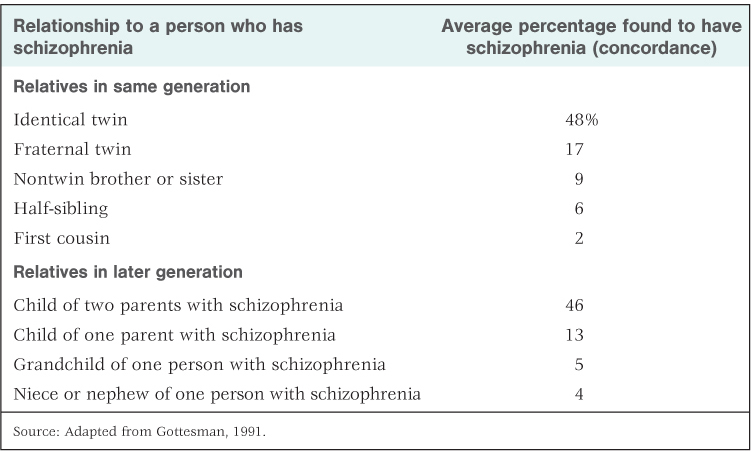

Schizophrenia was one of the first mental disorders to be studied extensively by behavior geneticists (Gottesman, 1991). In such studies, the first step is to identify a group of people, referred to as index cases, who have the disorder. Then the relatives of the index cases are studied to see what percentage of them have the disorder. This percentage is referred to as the concordance for the disorder, for the class of relatives studied. The average concordances found for schizophrenia in many such studies, for various classes of relatives, are shown in Table 16.4.

Concordance rates for schizophrenia

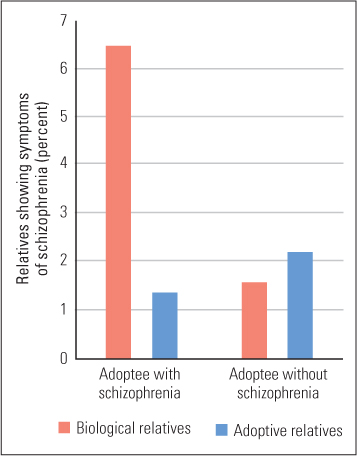

All in all, the results indicate that genetic differences among individuals play a substantial role in the predisposition for schizophrenia. The more closely related a person is to an index case, the greater is the chance that he or she will develop schizophrenia (Riley & Kendler, 2011). Other research, conducted with people who were adopted at an early age, shows high concordance for schizophrenia between biological relatives but not between adoptive relatives (Owen & O’Donovan, 2003). The results of one classic study of this type are shown in Figure 16.8. Such results indicate that it is the genetic similarity, not the environmental similarity, between relatives that produces high concordance for schizophrenia.

650

More recently a great deal of research has been aimed at identifying individual genes that contribute to the development of schizophrenia. Many different genes appear to be involved, and no single gene or small set of genes can account for most of the genetic influence in large samples of people with schizophrenia (Bertram, 2008). Consistent with current chemical theories of schizophrenia, at least some of the identified genes are known to influence dopamine neurotransmission, and some are known to influence glutamate neurotransmission (Bertram, 2008; Broome et al., 2005).

Effects of the Prenatal Environment and Early Brain Traumas

The data in Table 16.4 show that genes are heavily involved in the predisposition for schizophrenia, but they also show that genes are not the only determinants of the disorder. Of particular interest is the fact that the average concordance for schizophrenia for identical twins, 48 percent, is much less than the 100 percent that would be predicted if genes alone were involved. Another noteworthy observation in the table is that the concordance for schizophrenia in fraternal twins is considerably higher than that for nontwin pairs of full siblings—17 percent compared to 9 percent. This difference cannot be explained in terms of genes, as fraternal twins are no more similar to each other genetically than are other full siblings, but it is consistent with the possibility of a prenatal influence. Twins share the same womb at the same time, so they are exposed to the same prenatal stressors and toxins. That fact, of course, applies to identical twins as well as to fraternal twins, so some portion of the 48 percent concordance in identical twins may result not from shared genes but from shared prenatal environments.

27

What sorts of early disruptions to brain development have been implicated as predisposing causes of schizophrenia?

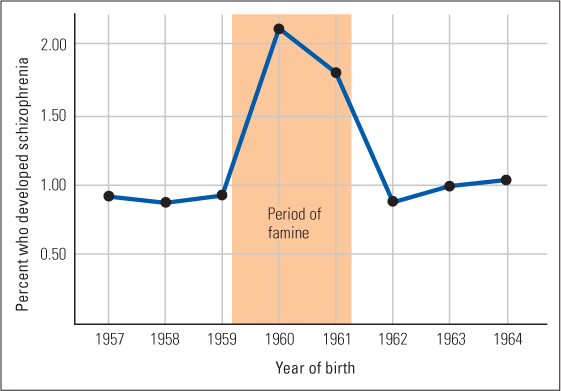

A number of studies have pointed to specific prenatal variables that can contribute to the likelihood of developing schizophrenia. One such variable is malnutrition (Brown & Susser, 2008). People born in the western Netherlands between October 15 and December 31, 1945, immediately following a severe famine brought on by a Nazi blockade of food supplies, are twice as likely as others born in the Netherlands to have developed schizophrenia (Susser et al., 1996). A more recent study, illustrated in Figure 16.9, revealed a similar effect for people who were born in China during or shortly after the Chinese famine of 1960–1961, which resulted from massive crop failures (St. Clair et al., 2005).

651

Prenatal viral infections and birth complications may also contribute to a predisposition for schizophrenia. Heightened rates of schizophrenia have been found in people whose mothers had rubella (also known as German measles) or certain other viral diseases during pregnancy and in people who had difficult births, involving oxygen deprivation or other trauma to the brain (Brown & Patterson, 2011; Tandon et al., 2008). There is also evidence that head injury later on in childhood, before age 10, can increase the likelihood of developing schizophrenia (AbdelMalik et al., 2003).

Effects of Life Experiences

The effects discussed so far are predisposing effects. Given a certain level of predisposition, the actual manifestation and course of schizophrenia may be influenced by one’s daily experiences. There is strong evidence that stressful life events of many sorts can precipitate schizophrenia and exacerbate its symptoms (Pallanti et al., 1997; van Os et al., 2008). Most research on such effects has focused on the family environment.

28

What evidence suggests that the family environment may promote schizophrenia, but only in those who are genetically predisposed for the disorder?

To date, the most thorough investigation of the effect of the family environment on schizophrenia is a 21-year-long study in Finland of two groups of adopted children (Tienari et al., 2004, 2006). One group of children was at high genetic risk for schizophrenia because their biological mothers were diagnosed with either schizophrenia or a milder schizophrenia-like disorder, and the other group was at low risk because neither of their biological parents showed any evidence of schizophrenia or a related disorder. The main finding was that those high-risk children whose adoptive parents communicated in a relatively disorganized, hard-to-follow, or highly emotional manner were much more likely to develop schizophrenia or a milder disorder akin to schizophrenia than were high-risk children whose adoptive parents communicated in a calmer, more organized fashion. This relationship was not found among the low-risk children. The results suggest that a degree of disordered communication at home that does not harm most children may have damaging effects on those who are genetically predisposed for schizophrenia.

Other research has centered on a concept referred to as expressed emotion, defined as criticisms and negative attitudes or feelings expressed about and toward a person with a mental disorder by family members with whom that person lives. Families high in expressed emotion tend to blame the diagnosed person for his or her disruptive or ineffective behavior rather than seeing it as something that he or she cannot control. Many studies indicate that, other things being equal, the greater the expressed emotion, the greater the likelihood that the active symptoms will return or worsen and the person will require hospitalization (Hooley, 2004; Tienari & Wahlberg, 2008). Moreover, a number of experiments have shown that support and training for family members, aimed at creating a more stable and accepting home environment and reducing expressed emotion, may significantly reduce the rate of relapse (Askey et al., 2007; Hooley & Hiller, 2001).

A Cross-Cultural Study of the Course of Schizophrenia

In the 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO) initiated an ambitious cross-cultural study of schizophrenia, involving, eventually, locations in 13 different nations. The nations included industrialized, developed countries, such as Germany, Japan, Ireland, and the United States, and relatively nonindustrialized, developing countries, such as India, Colombia, and Nigeria. Using agreed-upon criteria and cross-cultural reliability checks, the researchers diagnosed new cases of schizophrenia in each location, classed them according to symptom types and apparent severity, and reassessed each case through interviews conducted at various times in subsequent years. All in all, more than 1,000 people with schizophrenia were identified and followed over periods of up to 26 years (Hopper et al., 2007).

652

The results showed considerable cross-cultural consistency. The relative prevalence of the various symptoms, the severity of the initial symptoms, the average age of onset of the disorder, and the sex difference in age of onset (later for women than for men) were similar from location to location despite wide variations in the ways that people lived. However, the study also led to two overall conclusions that were quite surprising to many schizophrenia experts. The first surprising finding was that quite a high percentage of people, in all locations, were found to recover from schizophrenia; and the second was that the rate of recovery was greater in the developing countries than in the developed countries (Vahia & Vahia, 2008).

29

What cross-cultural difference has been observed in rate of recovery from schizophrenia? What are some possible explanations of that difference?

At the 2-year follow-up, for example, 63 percent of the patients in the developing countries, compared with 37 percent in the developed countries, showed full remission from schizophrenic symptoms (Jablensky et al., 1992). Subsequent follow-ups showed similar results and revealed that many of the originally recovered patients remained recovered over the entire study period (Hopper et al., 2007). Even among those who, on the basis of their initial symptoms, were identified as having a “poor prognosis,” 42 percent recovered in the developing countries, compared to 33 percent in the developed countries, by the WHO criteria.

Why should people in the poorer countries, which have the poorest mental health facilities, fare better after developing schizophrenia than people in the richer countries? Nobody knows for sure, but some interesting hypotheses have been put forth (Jenkins & Karno, 1992; Lin & Kleinman, 1988; López & Guarnaccia, 2005). Family members in less-industrialized countries generally place less value on personal independence and more on interdependence and family ties than do those in industrialized countries, which may lead them to feel less resentful and more nurturing toward a family member who needs extra care. They are more likely to live in large, extended families, which means that more people share in providing the extra care. Perhaps for these reasons, family members in less-industrialized countries are more accepting and less critical of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia than are those in industrialized countries. They show less expressed emotion, as defined earlier, which might account for the better recovery rate.

People in developing countries are also less likely to call the disorder “schizophrenia” or to think of it as permanent, and are more likely to refer to it as “a case of nerves,” which sounds more benign and ties it to experiences that everyone has had. Finally, in less-industrialized countries those with schizophrenia are more able to play an economically useful role. The same person who could not hold a 9-to-5 job can perform useful chores on the family farm, or at the family trade, or at a local business where everyone knows the family. Being less stigmatized, less cut off from the normal course of human activity, and better cared for by close family members and neighbors may increase the chance of recovery.

Another possible explanation, rarely mentioned in the psychiatric literature, has to do with drugs. Over the course of the WHO study, patients in the developed countries were generally treated with antipsychotic drugs for prolonged periods, as they are today. In contrast, patients in the developing countries were more often not treated with drugs or were treated only for short periods to bring the initial symptoms under control (Jablensky et al., 1992). The authors of the WHO study (Hopper et al., 2007) devote no discussion to the possible role of drugs in promoting or inhibiting recovery, but they do mention, in passing, that the treatment center in Agra, India, which had the highest rate of recovery of all the centers studied, was the only center that used no drugs at all—because they could not afford them.

653

Some controversial studies in Europe and the United States, some years ago, suggested that prolonged use of antipsychotic drugs, while dampening the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, may impede full recovery (Warner, 1985). This ironic possibility—that the drugs we use to treat schizophrenia might prolong the disorder—has not been followed up with systematic research.

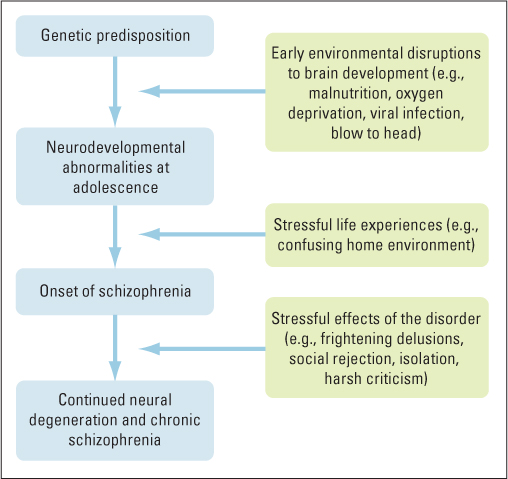

A Developmental Model of Schizophrenia

The more scientists learn about schizophrenia, the more apparent it becomes that the disorder has no simple, unitary cause. Figure 16.10 provides a useful framework (similar to one developed by Tsuang et al., 2001) for thinking about the multiple causes. The disorder is brought on by some combination of genetic predisposition, early physical disruptions to normal brain development, and stressful life experiences. Once the disorder begins, the disorder itself can have effects that help to prolong it, depending at least partly on how family members and others in one’s community respond. Distressing effects of the disorder itself, or of others’ reactions to it, can cause further deterioration of the brain and a more chronic course for the disorder.

SECTION REVIEW

Schizophrenia is a cognitive disorder with wide-ranging symptoms and multiple causes.

Diagnostic Characteristics

- Schizophrenia is characterized by various symptoms sometimes classified as positive, disorganized, and negative.

- Positive symptoms include delusions and auditory hallucinations.

- Disorganized symptoms include illogical thought and speech, and behaviors that are inappropriate to the environmental context.

- Negative symptoms include slowed movement, poverty of speech, flattened affect, and the loss of basic drives and the pleasure that comes from fulfilling them.

- Symptoms occur in a great variety of combinations and may change over time in the same person.

Underlying Cognitive and Neural Deficits

- The fundamental deficits in schizophrenia are cognitive, including problems with attention, working memory, and long-term memory.

- Abnormalities in brain chemistry, such as a decline in the effectiveness of glutamate or unusual patterns of dopamine activity, may help to explain the cognitive deficits.

- Structural differences in the brains of people with schizophrenia may include enlarged cerebral ventricles and reduced neural mass in some areas. Excessive pruning of neural cell bodies in adolescence may be a cause of some cases of schizophrenia.

Genetic and Environmental Causes

- Measures of concordance for schizophrenia in identical twins indicate substantial heritability. Some of the specific genes that appear to be involved have effects that are consistent with brain chemistry theories of the disorder.

- Predisposition may also arise from early environmental injury to the brain—including prenatal viruses or malnutrition, birth complications, or early childhood head injury.

- Stressful life experiences and aspects of the family environment can bring on the active phase of schizophrenia or worsen symptoms in predisposed people.

- Recovery from schizophrenia has been found to occur at higher rates in developing countries than in developed countries. Differences in living conditions and cultural attitudes and the lower use of antipsychotic drugs in developing countries may all play a role.

654