1.2 The Scope of Psychology

Psychology is a vast and diverse field. Every question about behavior and mental experience that is potentially answerable by scientific means is within its scope. One way to become oriented to this grand science is to preview the various kinds of explanatory concepts that psychologists use.

Varieties of Explanations in Psychology and Their Application to Sexual Jealousy

Psychologists strive to explain mental experiences and behavior. To explain is to identify causes. What causes us to do what we do, feel what we feel, perceive what we perceive, or believe what we believe? What causes us to eat in some conditions and not in others; to cooperate sometimes and to cheat at other times; to feel angry, frightened, happy, or guilty; to dream; to hate or love; to see red as different from blue; to remember or forget; to suddenly see solutions to problems that we couldn’t see before; to learn our native language so easily when we are very young; to become depressed or anxious? This is a sample of the kinds of questions that psychologists try to answer and that are addressed in this book.

The causes of mental experiences and behavior are complex and can be analyzed at various levels. The term level of analysis, as used in psychology and other sciences, refers to the level, or type, of causal process that is studied. More specifically, in psychology, a person’s behavior or mental experience can be examined at these levels:

13

- neural (brain as cause),

- physiological (internal chemical functions, such as hormones, as cause),

- genetic (genes as cause),

- evolutionary (natural selection as cause),

- learning (the individual’s prior experiences with the environment as cause),

- cognitive (the individual’s knowledge or beliefs as cause),

- social (the influence of other people as cause),

- cultural (the culture in which the person develops as cause),

- developmental (age-related changes as cause).

You will find many examples of each of these nine levels of analysis in this book. Now, as an overview, we’ll describe each of them very briefly. For the purpose of organization of this presentation, it is convenient to group the nine levels of analysis into two clusters. The first cluster—consisting of neural, physiological, genetic, and evolutionary explanations—is most directly biological. The second cluster, consisting of all of the remaining levels, is less directly biological and has to do with effects of experiences and knowledge.

Any given type of behavior or mental experience can, in principle, be analyzed at any of the nine levels. As you will see, the different levels of analysis correspond with different research specialties in psychology. To illustrate the different levels of analysis and research specialties in a real-world context, in the following paragraphs we will apply them to the phenomenon of sexual jealousy. For our purposes here, sexual jealousy can be defined as the set of emotions and behaviors that result when a person believes that his or her relationship with a sexual partner or potential sexual partner is threatened by the partner’s involvement with another person.

Explanations That Focus on Biological Processes

12

How do neural, physiological, genetic, and evolutionary explanations differ from one another? How would you apply these explanations toward an understanding of jealousy?

There are a variety of levels of biological explanations, from the actions of neurons and hormones to the functions of genes—and, taking a really big-picture perspective, the role of evolution.

Neural Explanations All mental experiences and behavioral acts are products of the nervous system. Therefore, one logical route to explanation in psychology is to try to understand how the nervous system produces the specific type of experience or behavior being studied. The research specialty that centers on this level of explanation is referred to as behavioral neuroscience.

Some behavioral neuroscientists study individual neurons (nerve cells) or small groups of neurons to determine how their characteristics contribute to particular psychological processes, such as learning. Others map out and study larger brain regions and pathways that are directly involved in particular categories of behavior or experience. For example, they might identify brain regions that are most involved in speaking grammatically, or in perceiving the shapes of objects, or in experiencing an emotion such as fear.

In one of the few studies to investigate neurological correlates of jealousy in humans, male college students induced to feel jealous showed greater activation in the left frontal cortex of their brains, as measured by electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings (described in Chapter 5) toward their “sexually” desired partner (Harmon-Jones et al., 2009). Previous research had shown that activation of the left frontal cortex is associated with approach-motivation, typically associated with pleasurable activities, whereas activation in the right frontal cortex is associated with withdrawal-motivation, typically corresponding to avoidance of negative stimuli. The researchers suggested that, at least initially, the primary motivational state in jealousy is one of approach, possibly aimed at preventing a threatening liaison between the target of one’s jealousy and another person, or at re-establishing their primary relationship.

14

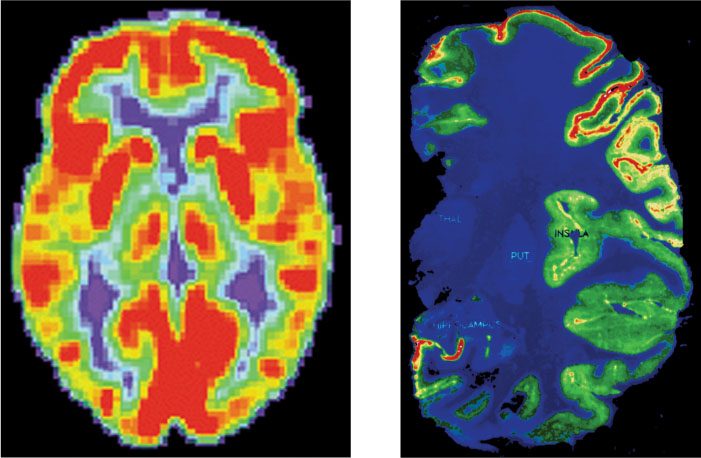

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory/Science Source

Jealousy can also be studied in nonhuman animals, and at least one neuroimaging study has been conducted with macaque monkeys (Rilling et al., 2004). The researchers made male monkeys jealous by exposing each one to the sight of a female with which he had previously mated being courted by another male. During this experience, the researchers measured the male monkey’s brain activity using a technique called positron emission tomography (PET, described in Chapter 5). The result was a preliminary mapping of specific brain areas that become especially active during the experience of sexual jealousy in male macaques.

A next step in this line of research might be to try to increase or decrease jealous behavior in monkeys by artificially activating or inactivating those same areas of the brain. Researchers might also examine people who have, through strokes or other accidents, suffered damage to those brain areas to determine if they have any deficits in the experience of jealousy. These are the kinds of techniques regularly used by behavioral neuroscientists.

Physiological Explanations Closely related to behavioral neuroscience is the specialty of physiological psychology, or biopsychology. Biopsychologists study the ways hormones and drugs act on the brain to alter behavior and experience, either in humans or in nonhuman animals. For example, we’re all familiar with the role that hormones play during puberty, influencing bodily growth and emotions; another example is the role of the steroid hormone cortisol in response to stress. Might hormones play a role in jealousy? David Geary and his colleagues (2001) investigated this in a pair of studies focusing mainly on young women. Geary reported that levels of the hormone estradiol were related to intensity of jealousy feelings, especially during the time of high fertility in women’s menstrual cycle. Estradiol, along with progesterone, is found in many common hormone-based birth-control methods. The connection between jealousy and estradiol suggests that some of women’s reproductively related behaviors and emotions may be significantly influenced by hormones, which may be disrupted by the use of hormone-based birth control.

15

Genetic Explanations Genes are the units of heredity that provide the codes for building the entire body, including the brain. Differences among individuals in the genes they inherit can cause differences in the brain and, therefore, differences in mental experiences and behavior. The research specialty that attempts to explain psychological differences among individuals in terms of differences in their genes is called behavioral genetics.

Some behavioral geneticists study nonhuman animals. For example, they may deliberately modify animals’ genes to observe the effects on behavior. Others study people. To estimate the role of genes in differences among people for some psychological trait, researchers might assess the degree to which people’s genetic relatedness correlates with their degree of similarity in that trait. A finding that close genetic relatives are more similar in the trait than are more distant relatives is evidence that genes contribute to variation in the trait. Behavioral geneticists might also try to identify specific genes that contribute to a trait by comparing the DNA (genetic material) of people who differ in that trait.

People differ in the degree to which they are prone to sexual jealousy. Some become jealous with much less provocation than do others. To measure the role of genetic differences in such behavioral differences, researchers might assess sexual jealousy in twins. If identical twins, who share all their genes with each other, are much more similar in jealousy than are same-sex fraternal twins, who are no more closely related than are other siblings, this would indicate that much of the variation among people in sexual jealousy is caused by variation in genes. A next step might be to find out just which genes are involved in these differences and how they act on the brain to influence jealousy. So far, to our knowledge, none of these types of studies have been done concerning sexual jealousy, but this book will describe such studies of intelligence (in Chapter 10), personality traits (in Chapter 15), and various other mental disorders (in Chapter 16).

Evolutionary Explanations All the basic biological machinery underlying behavior and mental experience is a product of evolution by natural selection. One way to explain universal human characteristics, therefore, is to explain how or why they came about in the course of evolution. The research specialty concerned with this level of analysis is called evolutionary psychology.

Some evolutionary psychologists are interested in the actual routes by which particular behavioral capacities or tendencies evolved. For instance, researchers studying the evolution of smiling have gained clues about how smiling originated in our ancestors by examining smile-like behaviors in other primates, including chimpanzees (discussed in Chapter 3). Most evolutionary psychologists are interested in identifying the evolutionary functions—that is, the survival or reproductive benefits—of the types of behaviors and mental experiences that they study. In later chapters we will discuss evolutionary, functional explanations of many human behavioral tendencies, drives, and emotions.

16

Evolutionary psychologists have examined the forms and consequences of human jealousy in some detail to identify its possible benefits for reproduction (Buss, 2000a&b; Easton & Shackelford, 2009). They have also studied behaviors in various animals that appear to be similar to human jealousy. Such research supports the view that jealousy functions to promote long-term mating bonds. All animals that form long-term bonds exhibit jealous-like behaviors; they behave in ways that seem designed to drive off, or in other ways discourage, any individuals that would lure away their mates (discussed in Chapter 3).

Explanations That Focus on Environmental Experiences, Knowledge, and Development

13

How do learning and cognitive explanations differ? How would you apply each of them toward an understanding of jealousy?

Humans, perhaps more than any other animal, are sensitive to conditions of their environment and change their behavior as a result of experience. Psychologists have developed different ways of explaining how people (as well as nonhuman animals) change in response to their environment, including learning (changes in overt behavior), cognition (changes in thinking), social (changes due to living with others), and development (changes over time).

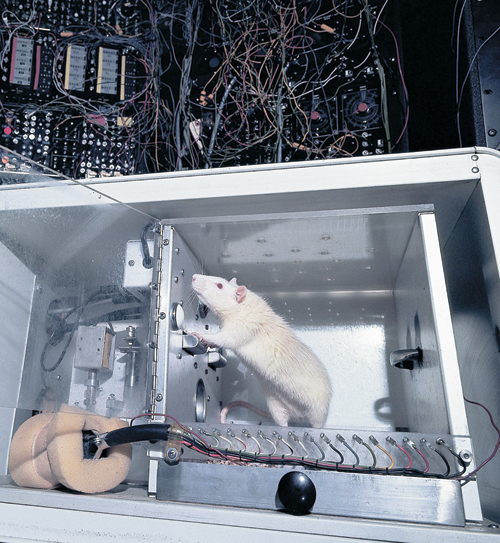

Learning Explanations Essentially all forms of human behavior and mental experience are modifiable by learning; that is, they can be influenced by prior experiences. Such experiences can affect our emotions, drives, perceptions, thoughts, skills, and habits. Most psychologists are interested in the ways that learning can influence the types of behavior that they study. The psychological specialty that is most directly and exclusively concerned with explaining behavior in terms of learning is appropriately called learning psychology. For historical reasons (which will become clear in Chapter 4), this specialty is also often called behavioral psychology.

Learning psychologists might, for example, attempt to explain compulsive gambling in terms of patterns of rewards that the person has experienced in the past while gambling. They also might attempt to explain a person’s fears in terms of the person’s previous experiences with the feared objects or situations. They might also conduct research, with animals or with people, to understand the most efficient ways to learn new skills (discussed in Chapter 4).

As we discussed earlier, differences in sexual jealousy among individuals derive partly from genetic differences. Learning psychology has found that they also derive partly from differences in past experiences. Jealous reactions that prove to be effective in obtaining rewards—such as those that succeed in repelling competitors or attracting renewed affection from the mate—may increase in frequency with experience, and ineffective reactions may decrease. People and animals may also learn, through experience, what sorts of cues are potential signs of infidelity in their mates, and those cues may come to trigger jealous reactions. The intensity of sexual jealousy, the specific manner in which it is expressed, and the environmental cues that trigger it can all be influenced, in many ways, by learning. A learning psychologist might study any of those effects.

Cognitive Explanations The term cognition refers to information in the mind—that is, to information that is somehow stored and activated by the workings of the brain. Such information includes thoughts, beliefs, and all forms of memories. Some information is conscious, in the sense that the person is aware of it and can describe it, and other information is unconscious but can still influence one’s conscious experiences and behavior. One way to explain any behavioral action or mental experience is to relate it to the cognitions (items of mental information) that underlie that action or experience. Note that cognition, unlike learning, is never measured directly but is inferred from the behaviors we can observe. The specialty focusing on this level of analysis is called cognitive psychology.

17

Think of mental information as analogous to a computer’s software and data, which influence the way the computer responds to new input. Cognitive psychologists are interested in specifying, as clearly as possible, the types of mental information that underlie and make possible the behaviors that they study. For instance, a cognitive psychologist who is interested in reasoning might attempt to understand the rules by which people manipulate information in their minds in order to solve particular classes of problems (discussed in Chapter 10). A cognitive psychologist who is interested in racial prejudice might attempt to specify the particular beliefs—including unconscious as well as conscious beliefs—that promote prejudiced behavior (discussed in Chapter 13). Cognitive psychologists are also interested in the basic processes by which learned information is stored and organized in the mind, which means that they are particularly interested in memory (discussed in Chapter 9).

In general, cognitive psychology differs from the psychology of learning in its focus on the mind. Learning psychologists typically attempt to relate learning experiences directly to behavioral changes and are relatively unconcerned with the mental processes that mediate such relationships. To a learning psychologist, experience in the environment leads to change in behavior. To a cognitive psychologist, experience in the environment leads to change in knowledge or beliefs, and that change leads to change in behavior.

A cognitive psychologist interested in jealousy would define jealousy first and foremost as a set of beliefs—beliefs about the behavior of one’s mate and some third party, about the vulnerability of one’s own relationship with the mate, and about the appropriateness or inappropriateness of possible ways to react. One way to study jealousy, from a cognitive perspective, is to ask people to recall episodes of it from their own lives and to describe the thoughts that went through their minds, the emotions they felt, and the actions they took. Such work reveals that a wide variety of thoughts can enter one’s mind in the jealous state, which can lead to actions ranging from romantic expressions of love, to increased attention to potential sexual competitors, to murderous violence (Maner et al., 2009; Maner & Shackelford, 2008). Psychotherapists who use cognitive methods to treat cases of pathological jealousy try to help their clients change their thought patterns so they will no longer misperceive every instance of attention that their mate pays to someone else as a threat to their relationship and will focus on constructive rather than destructive ways of reacting to actual threats (Ecker, 2012; Leahy & Tirch, 2008).

14

How do social and cultural explanations differ? How would you apply each of them toward an understanding of jealousy?

Social Explanations We humans are, by nature, social animals. We need to cooperate and get along with others of our species in order to survive and reproduce. For this reason, our behavior is strongly influenced by our perceptions of others. We use others as models of how to behave, and we often strive, consciously or unconsciously, to behave in ways that will lead others to approve of us. One way to explain mental experiences and behavior, therefore, is to identify how they are influenced by other people or by one’s beliefs about other people (discussed in Chapters 13 and 14). The specialty focusing on this level of explanation is called social psychology.

An often-quoted definition of social psychology (originally from Allport, 1968) is the following: “Social psychology is the attempt to understand and explain how the thought, feeling, and behavior of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others.” Social psychologists commonly attempt to explain behavior in terms of conformity to social norms, or obedience to authority, or living up to others’ expectations. A popular term for all such influences is social pressure.

18

Social-psychological explanations are often phrased in terms of people’s conscious or unconscious beliefs about the potential social consequences of acting in a particular way. This means that many social-psychological explanations are also cognitive explanations. Indeed, many modern social psychologists refer to their specialty as social cognition. A social psychologist interested in physical fitness, for example, might attempt to explain how people’s willingness to exercise is influenced by their beliefs about the degree to which other people exercise and their beliefs about how others will react to them if they do or do not exercise.

A social psychologist interested in jealousy might focus on the norms and beliefs concerning romance, mating, and jealousy that surround and influence the jealous person. How do others react in similar situations? Are the beloved’s flirtations with a third person within or outside the realm of what is considered acceptable by other dating or married couples? Would violent revenge be approved of or disapproved of by others who are important to the jealous person? Implicitly or explicitly, the answers to such questions influence the way the jealous person feels and behaves. An understanding of such influences constitutes a social-psychological explanation of the person’s feelings and behavior.

Cultural Explanations We can predict some aspects of a person’s behavior by knowing about the culture in which that person grew up. Cultures vary in language or dialect, in the values and attitudes they foster, and in the kinds of behaviors and emotions they encourage or discourage. Researchers have found consistent cultural differences even in the ways that people perceive and remember aspects of their physical environment (discussed in Chapters 9 and 10). The psychological specialty that explains mental experiences and behavior in terms of the culture in which the person developed is called cultural psychology.

Cultural and social psychology are very closely related but differ in emphasis. While social psychologists emphasize the immediate social influences that act on individuals, cultural psychologists strive to characterize entire cultures in terms of the typical ways that people within them feel, think, and act. While social psychologists use concepts such as conformity and obedience to explain an individual’s behavior, cultural psychologists more often refer to the unique history, economy, and religious or philosophical traditions of a culture to explain the values, norms, and habits of its people. For example, a cultural psychologist might contend that the frontier history of North America, in which individuals and families often had to struggle on their own with little established social support, helps explain why North Americans value independence and individuality so strongly.

Concerning jealousy, a cultural psychologist would point to significant cultural differences in romantic and sexual mores. For example, some cultures are more tolerant of extramarital affairs than are others, and this difference affects the degree and quality of jealousy that is experienced. Some cultures have a strong double standard that condemns women far more harshly than men for sexual infidelity, and in those cultures violent revenge on the part of a jealous man toward his mate may be socially sanctioned (Bhugra, 1993; Vandello & Cohen, 2008). In other cultures, the same violence would dishonor the perpetrator and land him in jail. A full cultural analysis would include an account of each culture’s history to examine differences in the ways infidelity is understood and treated.

15

What constitutes a developmental explanation? How would you apply a developmental explanation toward an understanding of jealousy?

Developmental Explanations Knowing a person’s age enables us to predict some aspects of that person’s behavior. Four-year-olds behave differently from 2-year-olds, and middle-aged adults behave differently from adolescents. The psychological specialty that documents and describes the typical age differences that occur in the ways that people feel, think, and act is called developmental psychology. Developmental psychologists may describe the sequence of changes that occur, from infancy to adulthood, for any given type of behavior or mental capacity. For example, developmental psychologists who study language have described a sequence of stages in speech production that goes from cooing to babbling, then to first recognizable words, to frequent one-word utterances, to two-word utterances, and so on, with each stage beginning, on average, at a certain age. At a superficial level, then, age itself can be an explanation: “She talks in such-and-such a way because she is 3 years old, and that is how most 3-year-olds talk.”

19

Looking deeper, developmental psychologists are also interested in the processes that produce the age-related changes that they document. Those processes include physical maturation of the body (including the brain), behavioral tendencies that are genetically timed to emerge at particular ages, the accumulated effects of many learning experiences, and new pressures and opportunities provided by the social environment or the cultural milieu as one gets older. At this deeper level, then, developmental psychology is an approach that brings together the other levels of analysis. Neural, physiological, genetic, evolutionary, learning, cognitive, social, and cultural explanations might all be brought to bear on the task of explaining behavioral changes that occur with age. Developmental psychologists are particularly interested in understanding how experiences at any given stage of development can influence behavior at later stages.

A developmental analysis of jealousy might begin with a description of age-related changes in jealousy that correspond with age-related changes in social relationships. Infants become jealous when their mother or other primary caregiver devotes extended attention to another baby (Hart, 2010). Children of middle-school age, especially girls, often become jealous when their same-sex “best friend” becomes best friends with someone else (Parker et al., 2005). These early forms of jealousy are similar in form and function to sexual jealousy, which typically emerges along with the first serious romantic attachment, in adolescence or young adulthood. Researchers have found evidence of continuity between early attachments to parents and friends and later attachments to romantic partners (discussed in Chapter 12). People who develop secure relationships with their parents and friends in childhood also tend, later on, to develop secure relationships with romantic partners, relatively untroubled by jealousy (Fraley, 2002; Main et al., 2005).

Levels of Analysis Are Complementary

These various levels of analysis provide different ways of asking questions about any psychological phenomenon, such as jealousy. However, these should not be viewed as alternative approaches to understanding, but rather as complementary approaches which, when combined, provide us with a more complete picture of important aspects of psychology. Although you may hear debates over the relative importance of genetic versus cultural influences on any behavior, even these most extreme levels of analysis should be viewed as complementary to one another, not as opposing poles of a philosophical argument. Genes are always expressed in a context, and culture constitutes an important component in that context. Wherever possible, throughout this book we will try to integrate findings from the various levels of analysis.

A Comment on Psychological Specialties

16

What are some research specialties in psychology that are defined primarily not by levels of analysis, but rather in terms of topics studied?

Because of psychology’s vast scope, research psychologists generally identify their work as belonging to specific subfields, or specialties. To some degree, as indicated in the foregoing discussion, different psychological research specialties correspond to different levels of analysis. This is most true of the nine specialties already described: behavioral neuroscience, biopsychology, behavioral genetics, evolutionary psychology, learning psychology, cognitive psychology, social psychology, cultural psychology, and developmental psychology.

20

Other specialties, however, are defined more in terms of topics studied than level of analysis. For example, sensory psychology is the study of basic abilities to see, hear, touch, taste, and smell the environment; and perceptual psychology is the study of how people and animals make sense of, or interpret, the input they receive through their senses. Similarly, some psychologists identify their specialty as the psychology of motivation or the psychology of emotion. These specialists might use any or all of psychology’s modes of explanation to understand particular phenomena related to the topics they study. And, of course, many psychologists combine specialties; they may describe themselves as cognitive cultural psychologists, social neuroscientists, evolutionary developmental psychologists, and so forth.

Two major specialties, which are closely related to each other, are devoted to the task of understanding individual differences among people. One of these is personality psychology (discussed in Chapter 15), which is concerned with normal differences in people’s general ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving—referred to as personality traits. The other is abnormal psychology (discussed in Chapter 16), which is concerned with variations in psychological traits that are sufficiently extreme and disruptive to people’s lives as to be classified as mental disorders. Personality psychologists and abnormal psychologists use various levels of analysis. Differences in the nervous system, in hormones, in genes, in learning experiences, in beliefs, in social pressures, or in cultural milieu may all contribute to an understanding of differences in personality and in susceptibility to particular mental disorders.

Closely related to abnormal psychology is clinical psychology (discussed in Chapter 17), the specialty that is concerned with helping people who have mental disorders or less serious psychological problems. Most clinical psychologists are practitioners rather than researchers. They offer psychotherapy or drug treatments, or both, to help people cope with or overcome their disorders or problems. Clinical psychologists who conduct research are usually interested in identifying or developing better treatment methods.

In general, research specialties in psychology are not rigidly defined. They are simply convenient labels aimed at classifying, roughly, the different levels of analysis and topics of study that characterize the work of different research psychologists. Regardless of what they call themselves, good researchers often use several different levels of analysis in their research and may study a variety of topics that in some way relate to one another. Our main reason for listing and briefly describing some of the specialties here has been to give you an overview of the broad scope of psychological science.

The Connections of Psychology to Other Scholarly Fields

17

What are the three main divisions of academic studies? How does psychology link them together?

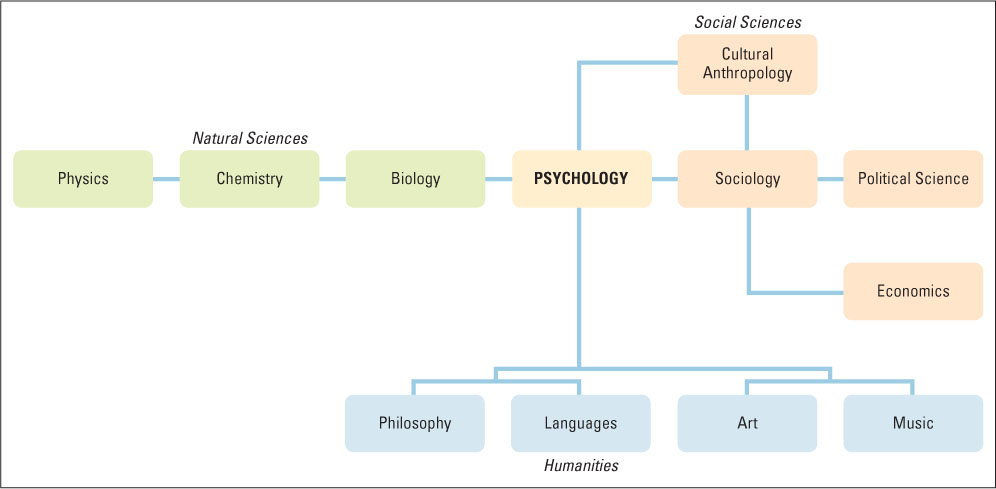

Another way to characterize psychology is to picture its place in the spectrum of disciplines that form the departments of a typical college of arts and sciences. Figure 1.3 illustrates a scheme that we call (with tongue only partly in cheek) the psychocentric theory of the university. The disciplines are divided roughly into three broad areas. One division is the natural sciences, including physics, chemistry, and biology, shown on the left side of the figure. The second division is the social sciences, including sociology, cultural anthropology, political science, and economics, shown on the right side of the figure. The third division is the humanities—including languages, philosophy, art, and music—shown in the lower part of the figure. The humanities represent things that humans do. Humans, unlike other animals, talk to one another, develop philosophies, and create art and music.

21

Where does psychology fit into this scheme? Directly in the center, tied to all three of the broad divisions. On the natural science end, it is tied most directly to biology by way of behavioral neuroscience, behavioral genetics, and evolutionary psychology. On the social science end, it is tied most directly to sociology and cultural anthropology by way of social and cultural psychology. In addition to bridging the natural and social sciences, psychology ties the whole spectrum of sciences to the humanities through its interest in how people produce and understand languages, philosophies, art, and music. It should not be surprising that psychology has such meaningful connections to other disciplines. Psychology is the study of all that people do. No wonder it is very often chosen as a second major, or as a minor, by students who are majoring in other fields.

Many students reading this book are planning to major in psychology, but many others are majoring in other subjects. No matter what you have chosen as your major field, you are likely to find meaningful connections between that field and psychology. Psychology has more connections to other subjects taught in the university than does any other single discipline (Gray, 2008).

Psychology as a Profession

Psychology is not only an academic discipline but also a profession. The profession includes both academic psychologists, who are engaged in research and teaching, and practicing psychologists, who apply psychological knowledge and ideas in clinics, businesses, and other settings. The majority of professional psychologists in the United States hold doctoral degrees in psychology, and most of the rest hold master’s degrees (Landrum et al., 2009). The main settings in which they work, and the kinds of services they perform in those settings, are:

- Academic departments in universities and colleges Academic psychologists are employed to conduct basic research, such as that which fills this book, and to teach psychology courses.

- Clinical settings Clinical and counseling psychologists work with clients who have psychological problems or disorders, in independent practice or in hospitals, mental health centers, clinics, and counseling or guidance centers.

- Elementary and secondary schools School psychologists administer psychological tests, supervise programs for children who have special needs, and may help teachers develop more effective classroom techniques.

- Business and government Psychologists are hired by businesses and government agencies for such varied purposes as conducting research, screening candidates for employment, helping to design more pleasant and efficient work environments, and counseling personnel who have work-related problems.

22

The decision to major in psychology as an undergraduate does not necessarily imply a choice of psychology as a career. Most students who major in psychology do so primarily because they find the subject fun to learn and think about. Most go on to careers in other fields—such as social work, law, education, and business—where they are quite likely to find their psychology background helpful (Kuther & Morgan, 2012; Landrum et al., 2009). If you are considering psychology as a career, you might want to look at the resources on careers in psychology that we have listed in the Find Out More section at the end of this chapter.

SECTION REVIEW

Psychology is a broad, diverse field of research, and it is a profession.

Levels of Causal Analysis and Topics of Study in Psychology

- Four types of biological causal explanations are used in psychology: neural, physiological, genetic, and evolutionary explanations.

- Five other types of causal explanations in psychology are learning, cognitive, social, cultural, and developmental explanations.

- As demonstrated with jealousy, each level of analysis can be applied to any given type of behavior or mental experience.

- Some subfields in psychology are defined primarily by the level of analysis; others are defined more by the topics studied.

A Discipline Among Disciplines

- Broadly speaking, scholarly disciplines can be classified as belonging to natural sciences, social sciences, or humanities.

- Psychology has strong connections with each class of disciplines.

The Profession of Psychology

- The profession includes academic psychologists, who teach and do research, and practicing psychologists, who apply psychological knowledge and principles to real-world issues.

- Psychologists work in various settings—including universities, clinical settings, and businesses—and typically hold advanced degrees.